Women in United States juries facts for kids

For the past 100 years, more and more women have been able to serve on juries in the United States. This change happened because of new laws and court decisions. Before the late 1900s, women were often not allowed to be on juries, or they could easily choose not to serve.

The fight for women's right to be on juries was a big deal. It was similar to the movement for women's right to vote. Many people debated about it in the news and elsewhere. Over time, court rulings at both federal and state levels helped more women join juries. Some states allowed women to serve much earlier than others. States also disagreed on whether getting the right to vote meant women also had the right to be on a jury.

Contents

History of Women on Juries

Long ago, there was a special group called a "jury of matrons." This was an early exception to women not being on juries. In the American colonies, these women were sometimes called to help in cases about pregnant women. They shared their knowledge about pregnancy and birth.

However, a legal thinker named William Blackstone believed women should be excluded from juries. He thought this was because of a "defect of sex." His ideas became part of the U.S. legal system. For many years, people argued against women on juries. They said women weren't smart enough, were too emotional, or needed to stay home. Women were caught between having full legal rights to serve or being completely banned.

Most reasons for keeping women off juries were based on the idea that women had other important duties at home. Many also believed women were too sensitive or not capable enough to be jurors. Some people who didn't want women on juries wanted to protect them from the unpleasant details of court cases. At the same time, women were starting to say they were just as capable as men. But for jury rights, they sometimes had to argue that men and women were different, not interchangeable.

The movement to include women on juries happened at the same time as the movement for women's right to vote. But even after women gained the right to vote, it wasn't clear if they also had the right to be on juries. The fight for women's jury rights was like a "second voting campaign."

The Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution says everyone has a right to a "speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury." Also, the Fourteenth Amendment talks about "Equal Protection." Because of these, how many men and women are on American juries has mostly been decided by Supreme Court rulings.

Today, it's possible to have all-female juries. For example, the jury in the State of Florida v. George Zimmerman case was made up entirely of women.

More Women on Juries After Voting Rights

In the 1930s and 1940s, middle-class women demanded to serve on juries. They saw it as a right of equal citizenship. During the Great Depression in the 1930s, money was tight. Groups like the League of Women Voters and the National Woman's Party pushed for women to be considered for jury duty. Even though women could vote since 1920, they didn't have the same duty to the state as men when it came to jury service.

Women started to demand service based on "female fairness and citizenship." They noticed they could work in some government jobs but not on juries. By 1937, women federal jurors were officially approved. In some states, like California and Ohio, jury duty became required for women.

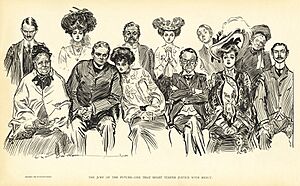

By the late 1930s, people's views on women jurors changed. Instead of being seen as emotional, women were seen as having special skills. They were thought to be "law abiding, attentive to detail, and less likely to be swayed by emotion than men." People even said women could "see through lies" because they had years of experience dealing with children who tried to avoid punishment. Women began to be seen as more "civilized" and "morally superior" than men. However, women who wanted to serve still had to volunteer. This meant mostly middle-class women who were strong activists served. They wanted to use their minds and test their judgment.

Judge John C. Knox wanted to expand who could be a juror. He even supported women serving. He hoped juries would "truly represent the community." But he also believed jurors should pass tests to prove they were literate and intelligent. He wanted federal courts to create "hand-picked juries" mainly of educated, middle-class men. These tests often kept out unemployed people or those whose clothing, speech, or spelling didn't meet certain standards.

How Media Showed Women Jurors

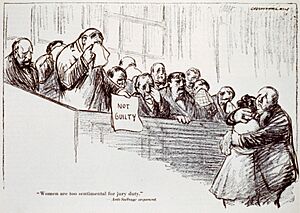

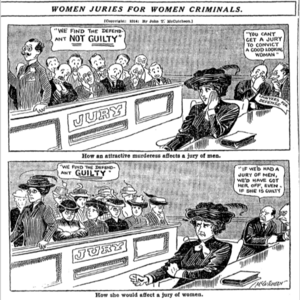

The media showed female jurors in both good and bad ways as women fought for the right to serve. This was similar to how women's voting rights were shown. Many of the same arguments for and against women voting were used for jury service. For example, some said both would disrupt women's home duties.

It was also believed that jury duty might not be good for women's "delicate nature." Some media stories claimed women would be swayed by handsome male criminals and let them go free. But others argued that men were already swayed by beautiful female criminals, and women on juries would balance this out.

While some states allowed women on juries right after they got the vote, most women had to fight for this right. In the 1920s, wealthy white men were preferred for juries. Groups focused on picking jurors, creating a pool of middle to upper-class white men. They left out people whose race, class, intelligence, or gender seemed "unfit." Juries were supposed to be a "mirror of society," but they often left out minorities, including women.

In the 1920s, common arguments were about "sentiment." Women were often stereotyped as unhelpful on a jury. A 1927 article from The New York Times claimed courts would have "fainting fits and outbursts of tears" if women were jurors. Also, past research suggested women were seen as "emotional, submissive, envious and passive." This led to biased juries.

Important Court Cases

Court cases were very important in the movement to include women in jury service. These cases slowly moved towards full inclusion of women. First, they looked at policies where women had to "opt-in" (choose to serve). Then, they looked at "opt-out" policies (where women could easily choose not to serve). Later, they looked at removing jurors based on gender. The main debate was whether jury service was a duty or a privilege of being a citizen, and if it could be optional.

Strauder v. West Virginia (1879)

The case of Strauder v. West Virginia was mainly about keeping African Americans off juries. The Supreme Court ruled that it was unconstitutional to exclude African Americans. However, the court said it was okay to exclude women, stating that a state "may confine the selection [of jurors] to males." This ruling set a pattern that was followed years later in Hoyt v. Florida.

Glasser v. United States (1942)

Glasser v. United States was one of the first important cases where the people on trial argued their jury was unfair because women were left out. The Supreme Court decided that an all-male jury was acceptable. In this case, the phrase "cross-section of the community" was first used. It means that officials should not pick jurors in a way that doesn't represent all kinds of people in the community.

Hoyt v. Florida (1961)

In Hoyt v. Florida, the Supreme Court agreed with Florida's policy where women had to "opt-in" to be on a jury. Mrs. Gwendolyn Hoyt was charged with a crime. At that time in Florida, women could serve on juries, but they had to sign up. Men were automatically registered. In Hoyt's county, only 220 women signed up, while 46,000 men were registered to vote. Hoyt argued that she didn't get a fair trial because of this "opt-in" policy, but she lost her case. The court's decision was based on the idea that jury service was a burden for women, not a responsibility. The court allowed women to be excused from jury service so they could take care of their duties at home.

Healy v. Edwards (1973)

Healy v. Edwards was not a Supreme Court case, but it was important. It challenged earlier rulings like Strauder v. West Virginia and Hoyt v. Florida. Ruth Bader Ginsburg was the lawyer for Marsha Healy. Ginsburg argued that Louisiana's optional jury service for women was unfair to three groups: women like Healy whose citizenship was lessened, women defendants who didn't have women on their juries, and men who had to serve more often because women weren't required to. Ginsburg said that "a distinct quality is lost if either sex is excluded."

Taylor v. Louisiana (1975)

The ruling in Taylor v. Louisiana was similar to Healy v. Edwards, but this was a Supreme Court case, so it overturned Hoyt v. Florida. Billy Taylor was accused of a serious crime. Louisiana had an "opt-in" policy for women jurors, like Florida. Taylor's jury was all men. He argued this violated his right to a fair jury. The court agreed with Taylor. It ruled that every defendant deserved a jury from a fair cross-section of the community. This case built on an earlier 1946 Supreme Court case, Ballard v. United States, which said excluding women from juries wasn't fair.

Duren v. Missouri (1979)

By 1979, many states had "opt-out" jury policies for women. This meant women could easily get out of jury service. The Supreme Court case Duren v. Missouri challenged these policies. Ruth Bader Ginsburg was again the lawyer. The court created a three-part test to find unfairness in jury selection. For a jury pool to be fair, it must regularly include a correct number of people from different groups in the population, like women. The court ruled that "opt-out" policies did not meet these rules and were therefore unconstitutional.

JEB v. Alabama (1994)

The Supreme Court case JEB v. Alabama was about a woman seeking child support. The lawyers used "peremptory strikes" to remove all the male jurors. Following an earlier ruling that banned removing jurors based on race, the Supreme Court also banned removing jurors based on gender. While earlier court decisions focused on the Sixth Amendment and the idea of a fair jury, JEB v. Alabama used the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Timeline of Women on Juries

The fight for women's jury rights happened state by state. Each state had its own challenges.

| Year women first allowed to serve | State | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1870 | Wyoming (territory) | Women in Wyoming Territory gained the right to vote in 1869. The Chief Justice believed this meant they could also serve on juries. So, in 1870, women served on mixed-gender juries. The first woman juror was Eliza Stewart Boyd. The Justice said the jury system improved with women. But when a new Justice took over in 1871, women were no longer called for jury duty. (1870, 1890–1892) |

| 1883 | Washington (territory) | Women in Washington Territory got voting and jury rights in 1883. But both were taken away in 1887 due to a change in the territory's Supreme Court. |

| 1898 | Utah | The Utah State Legislature allowed women to serve on juries in 1898, just three years after they got the right to vote. Even though they could serve, women could ask to be excused. They didn't regularly serve until the 1930s. |

| 1911 | Washington | |

| 1912 | Kansas | |

| Oregon | ||

| 1917 | California | |

| 1918 | Michigan | |

| Nevada | ||

| 1920 | Delaware | |

| Indiana | ||

| Iowa | ||

| Kentucky | ||

| Ohio | ||

| In 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote. This increased the push for jury rights in the remaining states. | ||

| 1921 | Arkansas | |

| Maine | ||

| Minnesota | ||

| New Jersey | ||

| North Dakota | ||

| Pennsylvania | ||

| Wisconsin | ||

| 1923 | Alaska (territory) | |

| 1924 | Louisiana | |

| 1927 | Rhode Island | |

| Connecticut | ||

| New York | ||

| 1939 | Illinois | |

| Montana | ||

| 1942 | Vermont | |

| 1943 | Idaho | |

| Nebraska | ||

| 1945 | Arizona | |

| Colorado | ||

| Missouri | ||

| 1947 | Maryland | |

| New Hampshire | ||

| North Carolina | ||

| South Dakota | ||

| 1949 | Florida | |

| Massachusetts | ||

| Wyoming | ||

| 1950 | Virginia | |

| 1951 | New Mexico | |

| Tennessee | ||

| 1952 | Hawaii | |

| Oklahoma | ||

| 1953 | Georgia | |

| 1955 | Texas | |

| 1956 | West Virginia | |

| 1966 | Alabama | |

| 1967 | South Carolina | |

| 1968 | Mississippi | On June 15, 1968, The New York Times reported that Mississippi was the last state to allow women to serve on state court juries. |

Women's Jury Service Today

Today, women often serve on juries. In many states, people who are caring for children can get special permission to be excused. For example, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Mississippi, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Oregon allow mothers who are nursing to be excused from jury service.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |