Sumatran rhinoceros facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sumatran Rhinoceros |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: |

Dicerorhinus

|

| Species: |

D. sumatrensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dicerorhinus sumatrensis |

|

The Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) is a special kind of rhinoceros. It is one of five types of rhinos still alive today. This rhino is the smallest of all rhinos. It stands about 120–145 centimetres (3.9–4.8 feet) tall at the shoulder. Its body is about 250 centimetres (98 inches) long. It weighs between 500–800 kilograms (1100–1760 pounds).

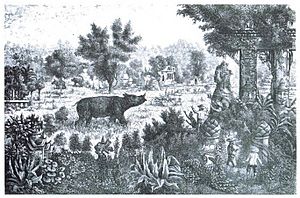

The Sumatran rhinoceros is a small, hairy rhino. It lives in small groups in the Indonesian and Malaysian rainforests. Only a few places in the world have Sumatran rhinos. These include the Cincinnati Zoo, the Los Angeles Zoo, and the Sumatran Rhino Sanctuary in Borneo.

Contents

What Does a Sumatran Rhino Look Like?

An adult Sumatran rhino is about 120 to 145 cm (3.9 to 4.8 ft) tall. Its body is around 250 cm (8.2 ft) long. It usually weighs 500 to 800 kg (1100 to 1760 lb). Some rhinos in zoos have weighed up to 2000 kg (4400 lb).

Like rhinos in Africa, the Sumatran rhino has two horns. The front horn, on its nose, is larger. It is usually 15 to 25 cm (6 to 10 in) long. The longest one ever found was 81 cm (32 in). The back horn is much smaller, often less than 10 cm (4 in). Sometimes, it is just a small bump. Both horns are dark grey or black. Male rhinos have bigger horns than females.

The Sumatran rhino has two thick skin folds. One is behind its front legs, and the other is before its back legs. It also has a smaller fold around its neck. Its skin is thin, about 10 to 16 mm (0.4 to 0.6 in) thick. Young rhinos have very dense hair. As they get older, their hair becomes less dense. It is usually reddish-brown. In the wild, their hair is often covered in mud. This makes it hard to see. Rhinos in zoos often have shaggier hair. This is because they do not rub against plants as much. They have long hair around their ears and a thick clump of hair on their tail. Like all rhinos, they cannot see very well. Sumatran rhinos are fast and can move easily. They can climb mountains and walk on steep slopes.

Where Do Sumatran Rhinos Live?

The Sumatran rhinoceros lives in both low and high areas. They live in rainforests, swamps, and cloud forests. They like hilly places near water. They prefer steep valleys with lots of plants.

Long ago, Sumatran rhinos lived in a large area. This area went as far north as Burma, eastern India, and Bangladesh. Some reports also said they lived in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Today, all known living rhinos are on the island of Sumatra. Some people hope rhinos still live in Burma. However, this is not very likely. It is hard to check due to problems in Burma. The last reports of rhinos in India were in the 1990s.

Sumatran rhinos are spread out far from each other. This makes it hard for people to protect them. Only four places are known to have Sumatran rhinos. These are Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park, Gunung Leuser National Park, and Way Kambas National Park on Sumatra. The fourth place is in Indonesian Borneo, west of Samarindah.

In the 1980s, Kerinci Seblat National Park in Sumatra had about 500 rhinos. But because of poaching, they are now gone from there. It is very unlikely that any rhinos still live in Peninsular Malaysia.

Scientists have studied the genes of Sumatran rhinos. They found three different groups of rhinos. Rhinos in eastern Sumatra and Peninsular Malaysia are closely related. This is because the sea levels were lower long ago. Sumatra was connected to the mainland then. The rhinos of Borneo are quite different. Scientists suggest not mixing them with other groups.

In 2013, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) found signs of rhinos in Kalimantan. This was in Borneo, where they were thought to be gone since the 1990s. They found fresh foot trails, mud holes, and marks on trees. In October 2013, videos from camera traps showed Sumatran rhinos there. Experts think it was two different rhinos. In 2016, a live female Sumatran rhino was found in Kalimantan. This was the first contact in over 40 years. She was moved to a safe place.

How Do Sumatran Rhinos Behave?

Sumatran rhinos usually live alone. They only come together to mate or when a mother raises her baby. Male rhinos have large home areas, up to 50 square kilometers (19 square miles). Female rhinos have smaller areas, about 10 to 15 square kilometers (4 to 6 square miles). Females' areas seem to be spaced apart. Males' areas often overlap. There is no sign that rhinos fight to protect their areas. They mark their areas by scraping the ground with their feet. They also bend small trees in special ways. And they leave their droppings.

Sumatran rhinos are most active in the morning and evening. During the day, they like to roll in mud baths. This helps them cool down and rest. In the rainy season, they move to higher places. In cooler months, they go back to lower areas. If there are no mud holes, they will dig puddles deeper with their feet and horns. Wallowing in mud helps them keep their body temperature steady. It also protects their skin from bugs. Rhinos in zoos that do not wallow enough can get skin problems. They can also have eye problems and lose hair.

Sumatran rhinos have no known natural enemies except humans. Tigers and wild dogs might kill a baby rhino. But babies stay close to their mothers. We do not know how often this happens. Rhinos share their living areas with elephants and tapirs. But they do not seem to compete for food or space. Elephants and rhinos even use the same trails. Many smaller animals, like deer and wild dogs, also use these trails.

Rhinos make trails throughout their home areas. Some are main trails used by many rhinos over time. These trails connect important places, like salt licks. Or they go through difficult areas. In feeding areas, rhinos make smaller trails. These trails are still covered by plants. They lead to places where the rhino finds food. Sumatran rhino trails have been found crossing rivers. These rivers can be deeper than 1.5 meters (5 feet) and about 50 meters (164 feet) wide. The currents can be strong. But the rhino is a good swimmer.

What Do Sumatran Rhinos Eat?

|

|

|

|

| Clockwise from top left: Mallotus, mangosteens, Ardisia, and Eugenia. | |

Most feeding happens just before night and in the morning. The Sumatran rhino eats plants. Its diet includes young trees, leaves, twigs, and shoots. Rhinos usually eat up to 50 kg (110 lb) of food each day. Scientists have found over 100 types of plants that rhinos eat. They mostly eat young trees with trunks about 1 to 6 cm (0.4 to 2.4 in) wide. The rhino pushes these trees over with its body. Then it walks over them without stepping on them to eat the leaves. They eat many different plants. This means they often change what they eat and where they feed. Some common plants they eat are from the Euphorbiaceae, Rubiaceae, and Melastomataceae families. The most common plant they eat is Eugenia.

The rhino's plant diet has a lot of fiber. It has a moderate amount of protein. Salt licks are very important for the rhino's health. These licks can be small hot springs or salty water seeps. They can also be mud-volcanoes. Salt licks are also important for rhinos to meet each other. Males visit them to find the scent of females ready to mate. Some rhinos live where salt licks are not common. These rhinos might get their minerals from plants that have a lot of them.

How Do Sumatran Rhinos Communicate?

The Sumatran rhinoceros is the rhino that makes the most sounds. Rhinos in zoos often make sounds. They also do this in the wild. They make three main sounds: eeps, whales, and whistle-blows. The eep is a short, one-second yelp. It is the most common sound. The whale sound is like the sounds of a humpback whale. It is like a song and lasts four to seven seconds. It is the second most common sound. The whistle-blow is a two-second whistle followed by a burst of air. It is the loudest sound. It is loud enough to make metal bars in a zoo shake.

We do not know why they make these sounds. But scientists think they might warn of danger or show where a rhino is. The whistle-blow can be heard from far away. Even in the thick forest where rhinos live. A similar sound from elephants can travel 9.8 km (6.1 mi). The whistle-blow might travel just as far. Sumatran rhinos sometimes twist small trees they do not eat. This twisting might be a way to communicate. It often shows a turn in a trail.

Sumatran Rhino Life Cycle

The mother rhino carries her baby for about 15–16 months. A baby rhino usually weighs 40–60 kg (88–132 lb) when born. The baby drinks its mother's milk for about 15 months. It stays with its mother for the first two to three years of its life. In the wild, a mother rhino usually has a new baby every four to five years. We do not know much about how they raise their young in the wild.

Images for kids

-

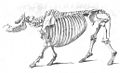

The preserved remains of "Subur", the last Sumatran rhinoceros in captivity by the 1970s. She died in 1972. "Subur" means "fertile" in Malay.

See also

In Spanish: Rinoceronte de Sumatra para niños

In Spanish: Rinoceronte de Sumatra para niños