E. O. Wilson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

E. O. Wilson

|

|

|---|---|

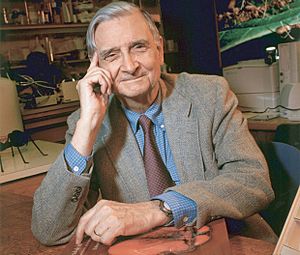

Wilson in 2007

|

|

| Born |

Edward Osborne Wilson

June 10, 1929 Birmingham, Alabama, U.S.

|

| Died | December 26, 2021 (aged 92) |

| Education | |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Irene Kelley

(m. 1955) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | A Monographic Revision of the Ant Genus Lasius (1955) |

| Doctoral advisor | Frank M. Carpenter |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Influences |

|

Edward Osborne Wilson (June 10, 1929 – December 26, 2021) was an important American biologist and naturalist. He was especially known for studying insects, particularly ants. He also created a new field of study called sociobiology.

Wilson was born in Alabama. From a young age, he loved exploring nature. When he was seven, a fishing accident damaged one of his eyes. This made him focus on studying "little things" like insects. He later became a professor at Harvard University. He won many awards, including two Pulitzer Prizes for his books. Wilson was also a strong voice for protecting our planet's biodiversity.

Contents

Early Life and His Love for Nature

Edward Osborne Wilson was born in Birmingham, Alabama, on June 10, 1929. He moved around a lot as a child. From a very young age, he was fascinated by nature. His parents even let him keep black widow spiders on their porch!

When he was seven, his parents divorced. In the same year, he had a fishing accident that blinded his right eye. Even though it was painful, he didn't complain. He wanted to keep exploring outside. This accident made him focus on small creatures. He could see tiny details with his good eye, like the hairs on insects. This led him to study insects instead of larger animals like birds.

Discovering Ants

At age nine, Wilson started exploring Rock Creek Park in Washington, D.C. He loved collecting insects, especially butterflies. One day, he found a group of bright yellow ants under the bark of a rotting tree. They smelled like lemons! This experience made a strong and lasting impression on him.

He also earned the Eagle Scout award. When he was 18, he wanted to study insects. During World War II, it was hard to get pins for collecting flies. So, he switched to collecting ants, which could be stored in small bottles. He even found the first colony of fire ants in the U.S. near Mobile, Alabama.

Education and Early Research

Wilson worried he couldn't afford college. He tried to join the Army to get money for school, but his eyesight prevented him. Luckily, he was able to attend the University of Alabama. He earned his bachelor's degree in 1949 and his master's in biology in 1950.

The next year, Wilson went to Harvard University for his PhD. He was chosen for the Harvard Society of Fellows, which allowed him to travel. He went on expeditions to Cuba, Mexico, Australia, and other places. He collected many different ant species. In 1955, he earned his PhD and married Irene Kelley.

Wilson's Amazing Career

From 1956 to 1996, Wilson taught at Harvard. He started by studying how ant species are classified. He also looked at how new species of ants developed. He created a theory called the "taxon cycle" to explain this.

Working with Other Scientists

Wilson worked with other scientists on important ideas. With mathematician William H. Bossert, he studied how insects communicate using chemicals called pheromones. In the 1960s, he teamed up with Robert MacArthur. They developed the theory of island biogeography. This theory explains how many different species can live on an island.

To test this idea, Wilson and Daniel S. Simberloff did an experiment. They removed all insects from tiny mangrove islands in Florida. Then, they watched how new species came back to repopulate the islands. Their book, The Theory of Island Biogeography, became a very important book in ecology.

Major Books and Ideas

In 1971, Wilson published The Insect Societies. This book suggested that insect behavior and other animal behaviors are shaped by similar evolutionary forces. He became the curator of entomology at Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology in 1973.

In 1975, he published Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. In this book, he applied his ideas about insect behavior to other animals, including humans. He suggested that some human social behaviors might be inherited. This idea was new and caused a lot of discussion.

His 1978 book, On Human Nature, explored how biology affects human culture. It won a Pulitzer Prize. Wilson also wrote The Ants with Bert Hölldobler in 1990, which won him another Pulitzer Prize.

Wilson was known as the "father of biodiversity" and the "ant man." David Attenborough called him a "magic name" because of his deep knowledge of ants and his wide understanding of the natural world.

Challenges and Criticisms

Not all of Wilson's ideas were accepted easily. His book Sociobiology received some negative reactions from other scientists. Some of his ideas about evolution also led to disagreements with other famous biologists.

After his death, some of his private letters were looked at. These letters showed that he had supported a psychologist whose work on human differences was seen as deeply flawed and racist by many scientists. The E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation later stated that they rejected Wilson's support for such ideas.

Key Contributions to Science

Sociobiology: The New Synthesis

Wilson used sociobiology to explain how social insects behave. Then, he applied these ideas to other animals, including humans. He believed that all animal behavior comes from a mix of heredity (what they inherit), their environment, and past experiences.

He argued that the basic unit of heredity is a gene. He also suggested that the idea of "group selection" was important for understanding social insects. This means that groups of animals can evolve together.

When applied to humans, sociobiology was very controversial. It challenged the idea that humans are born as a "blank slate" and that everything we learn comes from culture. Wilson suggested that some of our behaviors are influenced by our genes.

On Human Nature

In his 1978 book On Human Nature, Wilson wrote that "The evolutionary epic is probably the best myth we will ever have." This book helped make the phrase "epic of evolution" popular. It won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1979.

The Ants

Wilson and Bert Hölldobler studied ants very closely. Their huge book The Ants (1990) was a major work. It explained how ants behave in their colonies. Wilson argued that ants put the needs of their colony first. This is because individual ants cannot reproduce without a queen. So, they help the colony to survive and thrive.

Wilson famously said that "Karl Marx was right, socialism works, it is just that he had the wrong species." He meant that ants live in a way that benefits the whole group. But humans are different because we can reproduce on our own. So, individual humans tend to focus on their own survival and having their own children.

Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge

In his 1998 book Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, Wilson talked about how different areas of knowledge can be connected. He believed that all knowledge is one unified thing, not separate between science and humanities.

He used the term "consilience" to describe bringing together knowledge from different fields. He suggested that things like art appreciation or fear of snakes could be studied scientifically.

Beliefs and Environmental Work

Scientific Humanism

Wilson created the term scientific humanism. He believed this was the best way to understand the world and improve human life. In 2003, he signed the Humanist Manifesto.

God and Religion

Wilson described his view on God as "provisional deism." He preferred to be called an agnostic rather than an atheist. He believed that religious beliefs and rituals developed through evolution. He thought science should study them to understand their meaning for human nature.

In his book The Creation, Wilson urged scientists and religious leaders to work together. He said, "Science and religion are two of the most potent forces on Earth and they should come together to save the creation." However, in a 2015 interview, he also said that religion might need to be "eliminated" for human progress.

Protecting Our Planet (Ecology)

Wilson became very active in protecting biodiversity around the world. He studied how species were disappearing in the 20th century. He saw this as the biggest threat to Earth's future.

In 1984, he wrote Biophilia. This book explored why humans are naturally drawn to nature. It introduced the word biophilia, which shaped modern ideas about conservation. In 1988, he helped introduce the term biodiversity into common language.

Wilson was a consultant for many conservation groups. He famously said that destroying a rainforest for money was like burning a famous painting to cook a meal. In 2014, he suggested setting aside half of Earth's surface for other species. This idea became the basis for his book Half-Earth (2016) and the Half-Earth Project.

Wilson also helped start the Encyclopedia of Life (EOL). This project aims to create a global database of information on all known species. It now includes almost all 1.9 million species recognized by science. Wilson himself discovered and described over 400 species of ants!

Later Life and Legacy

Wilson officially retired from Harvard University in 1996. He continued to be a professor emeritus. After retiring, he published more than a dozen more books, including a digital biology textbook for the iPad.

He founded the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation. This foundation supports science writing and conservation efforts. Wilson and his wife, Irene, lived in Lexington, Massachusetts. He had one daughter, Catherine. His wife passed away in August 2021. Edward O. Wilson died on December 26, 2021, at the age of 92.

Awards and Honors

Wilson received many awards for his scientific work and his efforts to protect nature:

- Member of the National Academy of Sciences, elected 1969

- U.S. National Medal of Science, 1977

- Pulitzer Prize for On Human Nature, 1979

- Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, 1984

- Crafoord Prize, 1990

- Pulitzer Prize for The Ants (with Bert Hölldobler), 1991

- International Prize for Biology, 1993

- Carl Sagan Award for Public Understanding of Science, 1994

- Time magazine's 25 Most Influential People in America, 1995

- Benjamin Franklin Medal for Distinguished Achievement in the Sciences of the American Philosophical Society, 1998

- American Humanist Association's 1999 Humanist of the Year

- Nierenberg Prize, 2001

- Distinguished Eagle Scout Award 2004

- TED Prize 2007

- 2010 BBVA Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Ecology and Conservation Biology

- International Cosmos Prize, 2012

- Kew International Medal (2014)

Main Works

- The Theory of Island Biogeography, 1967, with Robert H. MacArthur

- The Insect Societies, 1971

- Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, 1975

- On Human Nature, 1979, winner of the 1979 Pulitzer Prize

- Biophilia, 1984

- The Ants, 1990, with Bert Hölldobler, winner of the 1991 Pulitzer Prize

- The Diversity of Life, 1992

- Naturalist (autobiography), 1994

- Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge, 1998

- The Future of Life, 2002

- The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth, 2006

- The Superorganism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies, 2009, with Bert Hölldobler

- Anthill: A Novel (his first novel), 2010

- The Social Conquest of Earth, 2012

- Letters to a Young Scientist, 2014

- Half-Earth, 2016

- Tales from the Ant World, 2020

See also

In Spanish: Edward Osborne Wilson para niños

In Spanish: Edward Osborne Wilson para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |