William Morton Wheeler facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Morton Wheeler

|

|

|---|---|

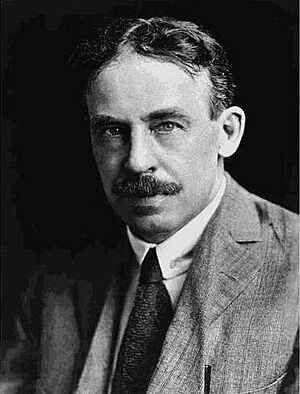

Wheeler in 1910

|

|

| Born | March 19, 1865 |

| Died | April 19, 1937 (aged 72) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Awards | Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal (1922) Leidy Award (1931) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Entomologist, Myrmecologist |

| Institutions | Harvard University American Museum of Natural History |

William Morton Wheeler (born March 19, 1865 – died April 19, 1937) was an American scientist who studied insects. He was an entomologist, which means he studied insects, and a myrmecologist, meaning he specialized in ants. He also taught as a professor at Harvard University.

Contents

William Morton Wheeler's Life

Early Years and Learning

William Morton Wheeler was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on March 19, 1865. From a very young age, he loved learning about nature. One time, he saw a moth caught in a spider's web, and it made him want to learn even more about the natural world.

He went to public school, but because he sometimes had trouble following rules, he was sent to a local German academy. This school was known for being very strict. After that, he attended a German normal school, which trained teachers. At both schools, he learned many subjects, including languages, philosophy, and science. He became very good at languages and could read French, German, Greek, Italian, Latin, and Spanish.

While at the German academy, Wheeler often visited the old natural history museum there. In 1884, a man named Henry August Ward brought a large collection of animal specimens to the academy. Wheeler was very excited and volunteered to help unpack and set up these new items. Ward was impressed by Wheeler's passion and offered him a job at his science business in Rochester, New York. Wheeler's first jobs included identifying birds and mammals. He later became a foreman, organizing collections of shells and other sea creatures.

Becoming a Scientist

In 1885, Wheeler went back to Milwaukee to teach German and physiology at a high school. He worked closely with the principal, George W. Peckham, and even helped him with his research on spiders and wasps.

Wheeler was also inspired by other scientists to study how insects develop from eggs, a field called embryology. He left the high school in 1887 and became a custodian at the Milwaukee Public Museum until 1890. During this time, he set up a small lab at home and studied embryology after work.

He then moved to help a professor at Clark University, where he earned his doctorate degree in philosophy in 1892. His main research was on insect embryology. After this, he started working at the University of Chicago in 1892 as an instructor in embryology. Before starting, he spent a year studying in Europe, visiting places like the Zoological Institute in Germany and the Naples Zoological Station in Italy.

A Career in Entomology

Wheeler returned to the University of Chicago in 1894 and taught embryology for five years. He kept publishing scientific papers, with about half of them being about insects. In 1898, he married Dora Bay Emerson in Chicago.

In 1899, he became a professor of zoology at the University of Texas at Austin. It was here that Wheeler became very interested in ants. He started studying their behavior and how to classify them. Ants soon became the main group of insects he focused on. Many students came to Texas to study with him, becoming well-known entomologists themselves.

In 1903, Wheeler left the University of Texas and became the "Curator of Invertebrate Zoology" at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. This meant he was in charge of the museum's collection of animals without backbones.

Wheeler was recognized for his important work. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1909 and the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1912. He also shared ideas with other ant scientists, like Horace Donisthorpe from Britain.

In 1922, Wheeler received the Daniel Giraud Elliot Medal for his book about ants from the American Museum Congo Expedition. He later became a professor of applied biology at Harvard University's Bussey Institute, which was a top place for biology studies in the United States.

In 1924, he spent time in Panama collecting invertebrates. Later, from 1931 to 1932, he led the Harvard Australian Expedition (1931–1932). This trip aimed to collect animal specimens for the Harvard Museum and study Australian animals in their natural homes. The expedition was very successful, bringing back many mammal and insect specimens to the United States.

Wheeler was also a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the Entomological Society of America. A type of gecko, Nephrurus wheeleri, was named in his honor. He wrote a total of 467 scientific papers and books during his career.

Images for kids

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |