Arnold Bennett facts for kids

Enoch Arnold Bennett (born May 27, 1867 – died March 27, 1931) was a famous English author. He is best known for his novels. He wrote a lot, completing 34 novels, seven collections of short stories, and 13 plays between the 1890s and 1930s. He also kept a daily journal with over a million words!

Bennett wrote articles and stories for more than 100 newspapers and magazines. During World War I, he worked for the Ministry of Information. In the 1920s, he even wrote for movies. His books sold very well, making him the most financially successful British author of his time.

He was born into a regular family in Hanley, a town in the Staffordshire Potteries. His father, a solicitor (a type of lawyer), wanted Arnold to follow in his footsteps. Arnold worked for his father before moving to London at age 21 to work for another law firm. He later became an assistant editor and then editor of a women's magazine. In 1900, he became a full-time writer.

Bennett loved French culture and literature. In 1903, he moved to Paris, France. Being there helped him feel more comfortable, especially around women, as he was very shy. He lived in France for ten years and married a French woman in 1907. In 1912, he moved back to England. He and his wife separated in 1921. He spent his last years with a new partner, an English actress. Arnold Bennett died in 1931 from typhoid fever, after drinking unsafe tap water in France.

Many of Bennett's novels and short stories are set in a made-up version of the Staffordshire Potteries, which he called "The Five Towns." He strongly believed that literature should be easy for everyone to read and enjoy. Because his books were so popular and realistic, some writers, like Virginia Woolf, didn't think highly of his work. After his death, his books were not as widely read. However, during his life, his "self-help" books sold many copies. He also had great success with two plays, Milestones (1912) and The Great Adventure (1913).

Today, experts like Margaret Drabble and John Carey have helped people appreciate Bennett's work again. His best novels, such as Anna of the Five Towns (1902), The Old Wives' Tale (1908), Clayhanger (1910), and Riceyman Steps (1923), are now seen as very important works of literature.

Arnold Bennett's Life and Career

Early Years and Education

Arnold Bennett was born on May 27, 1867, in Hanley, Staffordshire, England. This town is now part of Stoke-on-Trent. He was the oldest of six children. His father, Enoch Bennett, was a solicitor. The Bennett family was religious, musical, and enjoyed spending time with others. Even though his father could be strict, it was a happy home. The family moved several times as his father's law career grew.

From 1877 to 1882, Arnold went to school at the Wedgwood Institute in Burslem. He then spent a year at a grammar school in Newcastle-under-Lyme. He was good at Latin and excellent at French. His headmaster inspired him to love French literature and language, a passion that lasted his whole life. He did well in school and passed exams that could have led him to Oxbridge universities. However, his father had other plans for him.

In 1883, at age 16, Arnold left school and started working without pay in his father's law office. He did jobs he didn't enjoy, like collecting rent, during the day. In the evenings, he studied for exams. He also started writing small pieces for the local newspaper. He learned Pitman's shorthand, a useful skill for office work. This skill helped him get a job as a clerk at a law firm in Lincoln's Inn Fields, London. In March 1889, at 21, he moved to London and never lived in his hometown again.

Starting Out in London

In London, Bennett became friends with a colleague named John Eland, who loved books. This friendship helped Bennett with his shyness and a lifelong stammer. Together, they explored many different books. Writers who influenced Bennett included George Moore, Émile Zola, Honoré de Balzac, Guy de Maupassant, Gustave Flaubert, and Ivan Turgenev.

Bennett continued his own writing. In 1893, he won a prize for his story 'The Artist's Model'. Another short story, 'A Letter Home', was published in The Yellow Book in 1895, alongside famous writers like Henry James.

In 1894, Bennett left the law firm to become the assistant editor of Woman magazine. His salary was lower, but he had more time to write his first novel. For the magazine, he wrote under female pen names like "Barbara" and "Cecile." He learned about many different topics, from recipes to childcare, which helped him write about women's daily lives with understanding.

The magazine's informal office environment suited Bennett. It helped him feel more comfortable around young women. He kept working on his novel and wrote many short stories and articles. He was modest about his writing skills, but he knew he could write popular stories that people would enjoy. His first novel, A Man from the North, was published in 1898. It received good reviews, but Bennett didn't make much money from it.

In 1896, Bennett became the editor of Woman magazine. By then, he wanted to be a full-time author. During his four years as editor, he wrote two popular books: Journalism for Women (1898) and Polite Farces for the Drawing Room (1899). He also started his second novel, Anna of the Five Towns, which was set in his fictional "Five Towns" version of the Staffordshire Potteries.

Becoming a Full-Time Writer in Paris

In 1900, Bennett left his job at Woman magazine. He moved to a farm near Hockliffe in Bedfordshire, where he lived with his parents and younger sister. He finished Anna of the Five Towns in 1901, and it was published the next year. His next book, The Grand Babylon Hotel, was an exciting story about crime in high society. It sold 50,000 copies and was quickly translated into four languages.

In January 1902, Arnold's father passed away after a long illness. His mother moved back to Burslem, and his sister got married. With no one else to support, Bennett, who always loved French culture, decided to move to Paris in March 1903. Biographers believe he moved to find more freedom, overcome his shyness, and be seen as a serious artist. He lived in the 9th arrondissement of Paris for five years.

Life in Paris helped Bennett become much less shy around women. His journals mention a young woman he called "C" or "Chichi," a chorus girl. They spent a lot of time together.

In 1903, a small event in a restaurant gave Bennett an idea for what many consider his best novel. An old woman caused a scene, and the young waitress laughed at her. Bennett realized that the old woman had once been as young and beautiful as the waitress. This idea led to the story of two very different sisters in The Old Wives' Tale. He didn't start writing this novel until 1907. Before that, he wrote ten other books, some of which were lighter, more popular stories. Bennett often wrote popular books in between his more serious ones.

Marriage and Success in France and the US

In 1905, Bennett was engaged to Eleanor Green, an American woman living in Paris. However, she broke off the engagement at the last minute. In early 1907, he met Marguerite Soulié (1874–1960). They quickly became friends, then lovers. When Bennett became ill in May, Marguerite moved into his apartment to care for him. They grew closer, and in July 1907, shortly after his 40th birthday, they married. They did not have children. In early 1908, they moved from Paris to Fontainebleau-Avon, a town southeast of Paris.

While in France, Bennett wrote some of his most important novels, including Whom God Hath Joined (1906), The Old Wives' Tale (1908), and Clayhanger (1910). These books helped him become known as a major writer of realistic fiction. He also published lighter novels like The Card (1911). He wrote many articles for newspapers and magazines, including essays for "the general cultivated reader."

In 1911, Bennett visited the United States, which was very profitable for him. He wrote about his trip in his 1912 book Those United States. He visited New York, Boston, Chicago, and other cities. His publisher described his tour as "one of continuous triumph." He was interviewed 26 times in his first three days in New York! His "self-help" books, like How to Live on Twenty-Four Hours a Day and Mental Efficiency, were very popular in the US. He also sold the rights to his upcoming novels and essays for large sums of money.

During his ten years in France, Bennett went from being a moderately known writer to achieving outstanding success. His books sold widely, and critics highly praised his work.

Return to England and Wartime Work

In 1912, after a long stay in Cannes, France, Bennett and his wife moved back to England. They first lived in Putney, London. Then, he bought Comarques, a country house in Essex, and moved there in February 1913.

Once back in England, Bennett wanted to succeed as a playwright. He had tried before, but his plays weren't very strong. However, in 1911, he met playwright Edward Knoblauch. They worked together on Milestones, a play about a family over three generations (1860, 1885, and 1912). Bennett's storytelling talent combined with Knoblauch's experience made the play a huge success. It ran for over 600 performances in London and more than 200 in New York, earning Bennett a lot of money. His next play, The Great Adventure (1913), based on his novel Buried Alive, was also very successful.

During World War I, Bennett believed that British politicians had made mistakes, but that once the war started, Britain was right to join its allies. He focused on journalism, writing to inform and encourage people in Britain and other countries. He served on various committees. In 1915, he visited France to see the war front and write about it. His impressions were published in a book called Over There (1915). He also continued writing novels, including These Twain (1916) and The Roll Call (1917). His wartime novel The Pretty Lady (1918) caused some controversy due to its subject matter, and some booksellers refused to sell it.

In February 1918, Lord Beaverbrook became Minister of Information and appointed Bennett to lead propaganda efforts in France. When Beaverbrook fell ill, Bennett took charge of the entire ministry for the last weeks of the war. At the end of 1918, Bennett was offered a knighthood, but he declined it. He refused the offer again later.

As the war ended, Bennett returned to his interest in theatre. In November 1918, he became chairman of the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith. They produced successful plays like Abraham Lincoln and The Beggar's Opera, which ran for many performances.

Final Years and Legacy

In 1921, Bennett and his wife legally separated. They had grown apart over the years. Bennett sold his country house and lived in London for the rest of his life. For much of the 1920s, he was known as the highest-paid literary journalist in England. He wrote a weekly column for the Evening Standard called 'Books and Persons', which was very successful and influential. By the end of his career, Bennett had written for over 100 newspapers and magazines. He continued to write novels and plays as actively as before the war.

Bennett was known for his generosity. He supported many musicians, actors, poets, and painters. Hugh Walpole, James Agate, and Osbert Sitwell all spoke about Bennett's kindness. Sitwell remembered a letter where Bennett offered money to be given to young writers and artists who needed it, asking that his name not be revealed.

In 1922, Bennett met and fell in love with an actress named Dorothy Cheston (1891–1977). They set up home together in Cadogan Square. Since Marguerite would not agree to a divorce, Bennett could not marry Dorothy. In September 1928, Dorothy changed her name to Dorothy Cheston Bennett. In April 1929, they had a daughter, Virginia Mary. Dorothy continued her acting career, even starring in a successful revival of Milestones.

During a holiday in France in January 1931, Bennett drank tap water twice, which was not safe at the time. When he returned home, he became ill. It was first thought to be influenza, but it was actually typhoid fever. After several weeks of treatment, he passed away in his flat on March 27, 1931, at age 63.

Bennett was cremated, and his ashes were placed in his mother's grave in Burslem Cemetery. A memorial service was held in London, attended by many important people from the worlds of journalism, literature, music, politics, and theatre.

Arnold Bennett's Works

From the beginning, Arnold Bennett believed that art should be for everyone. He admired some of the modernist writers of his time, but he didn't like that they only wrote for a small group of people and looked down on the general reader. Bennett thought literature should be open and easy for ordinary people to understand.

Early in his career, Bennett saw the appeal of stories set in specific regions. Writers like Anthony Trollope, George Eliot, and Thomas Hardy had created their own fictional places. Bennett did the same with his "Five Towns," using his experiences growing up. As a realistic writer, he followed the examples of authors he admired, especially George Moore, and French writers like Balzac, Flaubert, and Maupassant. He also admired Russian writers like Dostoevsky, Turgenev, and Tolstoy. When writing about the Five Towns, Bennett wanted to show the lives of everyday people dealing with the rules and challenges of their communities.

Novels and Short Stories

Bennett is mostly remembered for his novels and short stories. His most famous works are set in, or feature people from, the six towns of the Potteries region where he grew up. He called this area "the Five Towns." These fictional towns are very similar to real ones: Bursley (Burslem), Hanbridge (Hanley), Longshaw (Longton), Knype (Stoke), and Turnhill (Tunstall).

The "Five Towns" first appear in Bennett's novel Anna of the Five Towns (1902). They are also the setting for other novels like Leonora (1903), Whom God Hath Joined (1906), The Old Wives' Tale (1908), and the Clayhanger trilogy: Clayhanger (1910), Hilda Lessways (1911), and These Twain (1916). They also appear in many of his short stories. Bennett described the Five Towns with a mix of humor and affection, showing provincial life and culture in great detail and creating many memorable characters. He said that reading George Moore's novel A Mummer's Wife, set in the Potteries, "opened my eyes to the romantic nature of the district I had blindly inhabited for over twenty years."

Bennett also based many of his characters on real people he knew. His friend John Eland inspired Mr. Aked in A Man from the North (1898). A Great Man (1903) has a character similar to his friend Chichi from Paris. The early life of Darius Clayhanger is based on a family friend, and Bennett himself is seen in the character of Edwin in Clayhanger.

These Twain is Bennett's last long story about life in the Five Towns. The novels he wrote in the 1920s are mostly set in London. For example, Riceyman Steps (1923), considered his best post-war novel, was set in Clerkenwell. It won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for novels in 1923. His book Lord Raingo (1926), a political novel, was influenced by Bennett's own experience in the Ministry of Information. Bennett's final and longest novel, Imperial Palace (1930), is set in a grand London hotel, similar to the Savoy.

Bennett often gave his novels subtitles, like "A fantasia on modern themes" or "A frolic." Literary experts often divide his novels into groups. One group includes his long, important stories like Anna of the Five Towns, The Old Wives' Tale, Clayhanger, and Riceyman Steps. These are highly regarded. Another group includes his "Fantasias" like The Grand Babylon Hotel (1902), which are less known today. His third group includes "Idyllic Diversions" or "Stories of Adventure," such as The Card (1911), which are still popular for their amusing look at different cultures and small-town life.

Bennett published 96 short stories in seven collections between 1905 and 1931. His feelings about his hometown are clearly seen in "The Death of Simon Fuge" from The Grim Smile of the Five Towns (1907), which is considered one of his best stories. His stories were set in many places, including Paris, Venice, London, and the Five Towns. Like his novels, he sometimes labeled his stories, calling "The Matador of the Five Towns" (1912) "a tragedy" and "Jock-at-a-Venture" from the same collection "a frolic." His short stories, especially those in Tales of the Five Towns (1905) and The Grim Smile of the Five Towns (1907), show his focus on realism, describing everyday life, even the dull or difficult parts. In 2010 and 2011, more of Bennett's previously uncollected short stories were published.

Plays and Screenplays

In 1931, critic Graham Sutton noted that while Bennett was a complete novelist, he was not a complete playwright. His plays often felt like they were written by a novelist, with long speeches and more focus on what characters were like than what they did.

Bennett's lack of theatre experience showed in some of his plays, like his 1911 comedy The Honeymoon. However, the very successful Milestones was well-structured, thanks to his collaborator, Edward Knoblauch. Bennett's most successful solo play was The Great Adventure, based on his 1908 novel Buried Alive. It ran for 674 performances in London. Sutton praised its "mischievous and sarcastic fantasy" and considered it a much better play than Milestones.

Bennett also wrote two opera libretti (the text for an opera) for composer Eugene Goossens: Judith (1929) and Don Juan (produced in 1937 after Bennett's death). Some critics felt Goossens's music lacked catchy tunes and Bennett's libretti were too wordy. However, critic Ernest Newman defended them, calling Judith "a drama told simply and straightforwardly" and Don Juan "the best thing that English opera has so far produced." Despite polite reviews, both operas were not performed much after their initial runs.

Bennett was very interested in movies. In 1920, he wrote The Wedding Dress, a script for a silent film. It was never made, and the full script was thought to be lost until his daughter found it in 1983. It was finally published in 2013. In 1928, Bennett wrote the script for the silent film Piccadilly, starring Anna May Wong. The British Film Institute calls it "one of the true greats of British silent films." In 1929, Bennett discussed writing a silent film called Punch and Judy with a young Alfred Hitchcock. However, they disagreed on artistic points, and Bennett refused to see it as a "talkie" (a film with sound). His original script was published in 2012.

Journalism and Self-Help Books

Bennett published more than two dozen non-fiction books. Eight of these were "self-help" books. The most famous is How to Live on 24 Hours a Day (1908), which is still in print and has been translated into many languages. Other self-help books include How to Become an Author (1903), The Reasonable Life (1907), Literary Taste: How to Form It (1909), The Human Machine (1908), Mental Efficiency (1911), The Plain Man and his Wife (1913), Self and Self-Management (1918), and How to Make the Best of Life (1923). These books were written to help ordinary people.

In the US, his self-help books were very popular with everyday readers. Bennett told his agent that these "pocket philosophies are just the sort of book for the American public." How to Live on 24 Hours a Day was first aimed at clerks and typists in Britain, offering them hope and understanding.

Bennett always had a strong interest in journalism. Throughout his life, he wrote for newspapers and magazines. For example, in 1908, he wrote over 60 newspaper articles, and in 1910, he wrote about 80. While living in Paris, he regularly contributed to T. P.'s Weekly. Later, he reviewed for The New Age under the name Jacob Tonson and was involved with the New Statesman.

Arnold Bennett's Legacy

Arnold Bennett Society

The Arnold Bennett Society was started in 1954. Its goal is to promote the study and appreciation of Arnold Bennett's life and works, as well as other writers from North Staffordshire. In 2021, Bennett's grandson, Denis Eldin, was the society's president.

In 2017, the society started an annual Arnold Bennett Prize to celebrate his 150th birthday. This prize is given to an author who was born, lives, or works in North Staffordshire and has published a book that year, or to an author whose book features the region.

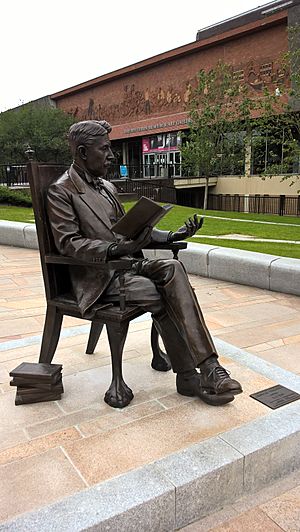

Plaques and Statues

Bennett has been honored with several plaques. One was placed at his country house, Comarques, in 1931. Another was put at his birthplace in Hanley the same year. A plaque and a bust (a sculpture of his head and shoulders) were unveiled in Burslem in 1962. There are also blue plaques (special markers on buildings) at the house in Cadogan Square where he lived from 1923 to 1930, and at the house in Cobridge where he lived as a youth. The entrance to Chiltern Court in Baker Street has plaques for both Bennett and H. G. Wells. A blue plaque is also on the wall of his home in Fontainebleau, France.

A two-meter-high bronze statue of Bennett stands outside The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent. It was unveiled on May 27, 2017, during the celebrations for his 150th birth anniversary.

Archives

Many of Bennett's papers and artworks are kept in archives. These include drafts of his writings, diaries, letters, photographs, and watercolors. You can find them at The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery in Stoke-on-Trent and at Keele University. Other papers are held by University College London, the British Library, and in the US, at Texas and Yale universities, and the Berg Collection in the New York Public Library.

Omelettes

Arnold Bennett is one of the few famous people, like composer Gioachino Rossini and singer Nellie Melba, to have a well-known dish named after him. An omelette Arnold Bennett is an omelette that includes smoked haddock, hard cheese (usually Cheddar), and cream. It was created for Bennett at the Savoy Grill in London, where he often ate, by chef Jean Baptiste Virlogeux. It is still a classic British dish, and many famous cooks have published their recipes for it. A version of it is still on the menu at the Savoy Grill today.

See also

In Spanish: Arnold Bennett para niños

In Spanish: Arnold Bennett para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |