Anthony Trollope facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Anthony Trollope

|

|

|---|---|

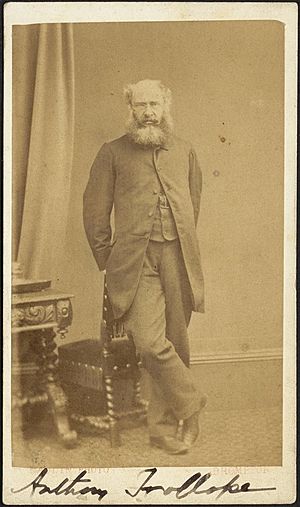

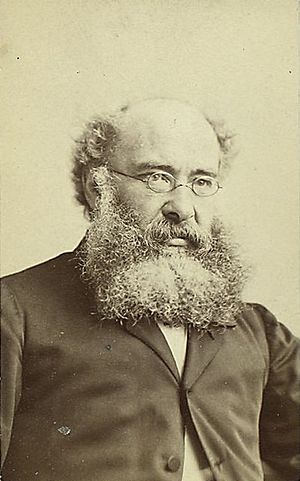

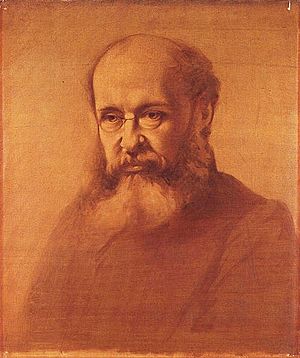

Portrait of Anthony Trollope, by Napoleon Sarony

|

|

| Born | 24 April 1815 London, England

|

| Died | 6 December 1882 (aged 67) Marylebone, London, England

|

| Education | Harrow School Winchester College |

| Occupation | Novelist; civil servant (Post Office) |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse(s) |

Rose Heseltine

(m. 1844) |

| Children | 2 |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Anthony Trollope (born April 24, 1815 – died December 6, 1882) was a famous English novelist and government worker (called a civil servant) during the Victorian era. He is best known for his series of novels called the Chronicles of Barsetshire. These books are set in a made-up county called Barsetshire. He also wrote many other novels about politics, society, and how men and women lived in his time.

Even though his books were very popular during his life, people didn't think as highly of his writing right after he died. But by the middle of the 1900s, critics started to appreciate his work again.

Contents

Biography

Anthony Trollope was the son of Thomas Anthony Trollope, a lawyer, and Frances Milton Trollope, a novelist and travel writer. His father was smart and well-educated, but he struggled with his law career and farming. The family often had money problems, even though they came from a good background.

Anthony was born in London. He went to Harrow School from age seven, attending as a day student because his family's farm was nearby. He later went to Winchester College for three years, then returned to Harrow. He had a very tough time at these schools. They were top schools, but Anthony had little money and few friends. He was often bullied. To escape, he would daydream and create detailed imaginary worlds.

In 1827, his mother, Frances Trollope, moved to America with his younger siblings. She tried to start a business there, but it didn't work out. Anthony stayed in England. His mother returned in 1831 and became a successful writer, earning good money. However, his father's financial problems got worse. In 1834, his father moved to Belgium to avoid being arrested for debt. The whole family joined him, living on Frances's earnings.

While in Belgium, Anthony was offered a job in the Austrian army. To take it, he needed to learn French and German. He took a job as an assistant teacher in a school in Brussels to learn these languages for free. After six weeks, he got an offer for a clerk position at the General Post Office in London, thanks to a family friend. He returned to London in late 1834 to start this job. His father died the next year.

Trollope later said that his first seven years at the Post Office were not good. He was often late and had trouble following rules. He also had a large debt that caused him constant worry. He disliked his job but felt stuck.

Move to Ireland

In 1841, Trollope got a chance to change his life. A Post Office job in central Ireland needed someone new. It wasn't a popular job, but Trollope, who was in debt and having problems at work, volunteered for it. His boss was happy to let him go.

Trollope moved to Banagher, in Ireland. His job involved inspecting post offices, which meant a lot of travel. Even though he had a bad reputation from his London office, his new boss decided to judge him fairly. Trollope said that within a year, he was seen as a valuable worker. His salary and travel money went much further in Ireland than in London, and he became more financially stable. He also started fox hunting, which he loved for the next 30 years. His job allowed him to meet many Irish people, and he found them friendly and smart.

In Ireland, Trollope met Rose Heseltine (1821–1917). They got engaged after he had been in Ireland for a year. Because of his debts, they couldn't marry until 1844. Their first son, Henry, was born in 1846, and their second, Frederick, in 1847. Soon after they married, Trollope was moved to another postal area in southern Ireland, and the family moved to Clonmel.

Early works

Trollope decided he wanted to be a novelist, but he didn't write much during his first three years in Ireland. By the time he married, he had only written the first part of his first novel, The Macdermots of Ballycloran. He finished it within a year of his marriage.

Trollope often wrote during his long train trips for his Post Office duties. He set strict goals for how much he would write each day. This helped him become one of the most productive writers ever. He even got ideas for his stories from the "lost-letter" box at the Post Office.

Many of his first novels were set in Ireland. This was natural since he lived and worked there. However, English readers at the time were not very interested in stories about Ireland. Some critics say that Trollope's view of Ireland was different from other Victorian novelists. Other critics argue that Ireland didn't influence him as much as England did, and that the country's problems, like the Great Famine, hurt his writing. But these ideas have been criticized for being unfair to Ireland.

Trollope published four novels about Ireland. Two were written during the Great Famine, and a third dealt with the famine as a topic. These included The Macdermots of Ballycloran, The Kellys and the O'Kellys, and Castle Richmond. The Kellys and the O'Kellys (1848) is a funny story comparing the love lives of a wealthy landlord and his Catholic tenant. He also wrote two short stories about Ireland. Some people believe his Irish works tried to show a connection between Irish and British identity.

His Irish books were not very popular. Publishers told him that readers preferred novels about other subjects. Magazines often had negative reviews about Ireland, which made English readers less likely to read books set there.

Success as an author

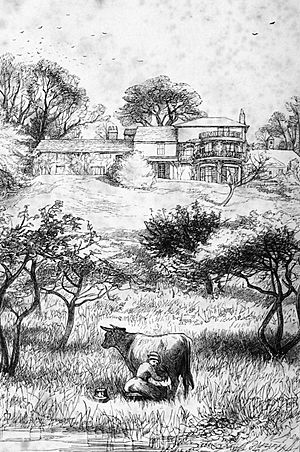

In 1851, Trollope was sent to England to improve mail delivery in the southwest and south Wales. This two-year job took him across much of Great Britain, often on horseback. Trollope called this time "two of the happiest years of my life."

During this time, he visited Salisbury Cathedral. There, he got the idea for The Warden, which became the first of his six Barsetshire novels. He couldn't start writing for a year because of his Post Office work. The novel was published in 1855. He earned a small amount from it, but the book got good reviews and made him known to readers.

He immediately started writing Barchester Towers, the second Barsetshire novel. When it was published in 1857, he received an advance payment. Like The Warden, it didn't sell huge numbers, but it helped build his reputation. Trollope wrote that it was "one of the novels which novel readers were called upon to read." For his next novel, The Three Clerks, he sold the full rights for a single payment, which he preferred to waiting for profits.

Return to England

Trollope was happy in Ireland, but he felt that as an author, he should live closer to London. In 1859, he got a Post Office job as a Surveyor for the Eastern District of England. Later that year, he moved to Waltham Cross, about 12 miles (19 km) from London, where he lived until 1871.

In late 1859, Trollope heard about a new magazine called the Cornhill Magazine. He wrote to the editor, William Makepeace Thackeray, offering to write short stories. Both Thackeray and the publisher, George Murray Smith, responded. Smith offered Trollope a large sum for a novel if he could deliver a big part of it quickly. Trollope offered Castle Richmond, but Smith wanted a story about English church life, like Barchester Towers. So, Trollope created the plot for Framley Parsonage, setting it near Barchester to use characters from his other novels.

Framley Parsonage became incredibly popular. It made Trollope famous with the reading public and showed that Smith's high payment was worth it. This early connection to Cornhill also brought Trollope into the London world of artists, writers, and thinkers.

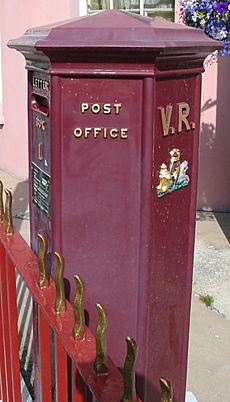

By the mid-1860s, Trollope had a senior position at the Post Office. He is credited with bringing the pillar box (the common mail-box) to the United Kingdom. He was earning a lot of money from his novels. He had overcome his difficult youth, made good friends, and enjoyed hunting. In 1865, Trollope helped start the liberal Fortnightly Review magazine.

In 1867, Trollope resigned from the Post Office. By then, he had saved enough money to earn an income equal to the pension he would have received if he had stayed until age 60.

Beverley campaign

Trollope had always dreamed of becoming a member of the House of Commons, which is like a parliament. As a government worker, he couldn't do this. When he left the Post Office, he immediately started looking for a place to run for election. In 1868, he agreed to run as a Liberal candidate in the town of Beverley.

Party leaders seemed to take advantage of Trollope's eagerness and willingness to spend money on his campaign. Beverley had a history of vote-buying and threats during elections. It was known that many voters would sell their votes. The goal for a Liberal candidate was not necessarily to win, but to show that the Conservative candidates were using unfair methods.

Trollope described his time campaigning in Beverley as "the most wretched fortnight of my manhood." He spent a lot of money on his campaign. The election was on November 17, 1868. Trollope came in last. An investigation later found widespread corruption in the election, and the town lost its right to elect members of parliament in 1870. Trollope used this experience in his novels, like in the fictional Percycross election in Ralph the Heir.

Later years

After losing the election in Beverley, Trollope focused completely on his writing. He continued to write novels quickly. He also edited St Paul's Magazine, which published some of his novels in parts.

Between 1859 and 1875, Trollope visited the United States five times. He met many American writers, including James Russell Lowell, Mark Twain, and Henry James.

Trollope wrote a travel book about his experiences in the U.S. during the American Civil War called North America (1862). He knew his mother had written a very negative book about America. Trollope felt more friendly towards the United States and wanted to write a book that would "add to the good feeling" between the two countries. While in America, Trollope strongly supported the Union (the North) because he was against slavery.

In 1871, Trollope took his first trip to Australia, arriving in Melbourne with his wife and cook. They went to visit their younger son, Frederick, who was a sheep farmer. Trollope wrote his novel Lady Anna during the journey. In Australia, he spent over a year exploring mines, meeting workers, riding horses into the countryside, and visiting different places. He even visited the old prison colony of Port Arthur. However, the Australian newspapers were worried he would write bad things about Australia, like his mother and Charles Dickens had done about America. When he returned, Trollope published Australia and New Zealand (1873). He had both good and bad things to say. He liked that there was less focus on social classes, but he was negative about some towns and the Aboriginal people. What made Australians most angry were his comments calling them "braggarts" (people who boast a lot).

Trollope returned to Australia in 1875 to help his son close his failed farm business. He found that people still remembered his comments about bragging. Even after he died in 1882, Australian papers still mentioned these accusations and didn't fully praise his achievements.

In the late 1870s, Trollope traveled to southern Africa, visiting the Cape Colony and the Boer Republics. He wrote a book called South Africa (1877). He described the mining town of Kimberly as "one of the most interesting places on the face of the earth."

In 1880, Trollope moved to the village of South Harting. He spent some time in Ireland in the early 1880s researching his last, unfinished novel, The Landleaguers. He was very upset by the violence of the Land War there.

Death

Anthony Trollope died in Marylebone, London, in 1882. He is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, near the grave of another famous writer, Wilkie Collins.

Works and reputation

Trollope's first big success was The Warden (1855). This was the first of six novels set in the made-up county of "Barsetshire," often called the Chronicles of Barsetshire. These books mainly focused on the lives of church leaders and wealthy landowners. Barchester Towers (1857) is probably the most famous of these. Trollope also wrote another major series, the Palliser novels, which were about politics. These books featured the rich and hardworking Plantagenet Palliser (who later became a Duke) and his lively wife, Lady Glencora. Many other interesting characters appeared in these novels too.

Trollope's popularity and critical success went down in his later years. However, he kept writing a lot, and some of his later novels are now highly regarded. For example, many critics today see The Way We Live Now (1875), which makes fun of society, as his best work. In total, Trollope wrote 47 novels, 42 short stories, and five travel books. He also wrote non-fiction books about famous people like William Makepeace Thackeray and Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston.

After he died, Trollope's book An Autobiography was published and became a bestseller. However, this book also caused his reputation to suffer among critics. Even during his life, reviewers often complained about how much he wrote. But when Trollope revealed in his autobiography that he stuck to a strict daily writing schedule and admitted he wrote for money, it confirmed critics' worst fears. Writers were expected to wait for inspiration, not follow a timetable.

Some writers, like Julian Hawthorne, praised Trollope as a person but felt his novels had harmed English literature. Henry James also had mixed feelings. He sometimes wrote harsh reviews of Trollope's novels. James also disliked how Trollope would talk directly to the reader in his novels, explaining how he could change the story.

However, many famous writers like William Thackeray, George Eliot, and Wilkie Collins admired Trollope and were his friends. George Eliot even said she couldn't have written her big novel Middlemarch without Trollope showing the way with his detailed, fictional Barsetshire county. Other people praised Trollope's understanding of everyday life, government offices, and business. He is one of the few novelists who showed the office as a creative place. The poet W. H. Auden wrote that Trollope understood the role of money better than almost any other novelist.

As novels became more focused on personal feelings and new artistic styles, Trollope's standing with critics suffered. But in 1934, Lord David Cecil noted that "Trollope is still very much alive." He also said that Trollope was "free from the most typical Victorian faults." In the 1940s and again in the 1960s and 1990s, there were efforts to bring back his good reputation. Today, some critics are especially interested in how Trollope showed women in his novels. Even in his own time, people noticed his deep understanding of the challenges women faced in Victorian society.

In the early 1990s, interest in Trollope grew. There are now Trollope Societies in the United Kingdom and the United States. In 2011, the University of Kansas started giving out an annual Trollope Prize to draw attention to his work.

Many famous people have been fans of Trollope, including actor Alec Guinness, former British prime ministers Harold Macmillan and Sir John Major, and economist John Kenneth Galbraith. The banker Siegmund George Warburg even said that "reading Anthony Trollope surpassed a university education."

See also

In Spanish: Anthony Trollope para niños

In Spanish: Anthony Trollope para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |