Bal Gangadhar Tilak facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lokmanya

Bal Gangadhar Tilak

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Keshav Gangadhar Tilak

23 July 1856 |

| Died | 1 August 1920 (aged 64) |

| Occupation | Author, politician, freedom fighter |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Movement | Indian Independence movement |

| Spouse(s) | Satyabhamabai Tilak |

| Children | 3 |

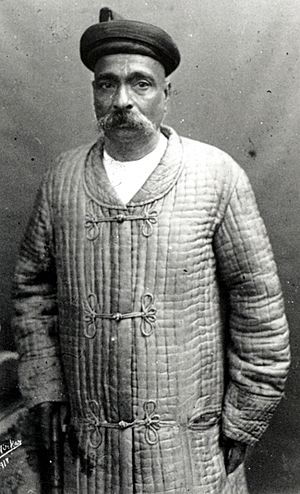

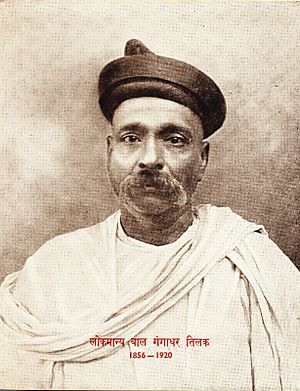

Bal Gangadhar Tilak (born Keshav Gangadhar Tilak; 23 July 1856 – 1 August 1920) was an important Indian nationalist, teacher, and freedom fighter. People lovingly called him Lokmanya, which means "accepted by the people as their leader". He was one of the first big leaders of the Indian independence movement. The British rulers called him "The father of the Indian unrest" because he challenged their rule. Mahatma Gandhi later called him "The Maker of Modern India".

Tilak was one of the first and strongest supporters of Swaraj ('self-rule'). He believed India should govern itself. He is famous for his powerful quote in Marathi: "Swaraj is my birthright and I shall have it!". He worked closely with other Indian National Congress leaders like Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah. He was part of a famous trio known as Lal Bal Pal.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Keshav Gangadhar Tilak was born on 23 July 1856 in Ratnagiri, which is now in Maharashtra. His family were Marathi Hindus. His father, Gangadhar Tilak, was a school teacher and a Sanskrit expert. Sadly, his father passed away when Tilak was sixteen. In 1871, Tilak married Tapibai, who later changed her name to Satyabhamabai.

He studied hard and earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in Mathematics from Deccan College in Pune in 1877. He then studied law and received his L.L.B degree in 1879. After finishing his studies, Tilak first taught mathematics. Later, he became a journalist, using his writing to share his ideas with the public. He believed that serving his country was like serving God.

Tilak was inspired by Vishnushastri Chiplunkar. In 1880, he helped start the New English School with friends. Their main goal was to give young Indians a better education. This school was so successful that they created the Deccan Education Society in 1884. This society aimed to teach young Indians about their own culture and nationalist ideas. They even started Fergusson College in 1885 for higher studies. Tilak taught mathematics there. In 1890, Tilak left the society to focus more on political work. He wanted to start a big movement for independence by bringing back Indian culture and religious pride.

Political Journey

Tilak spent many years fighting for India to be free from British rule. Before Gandhi became famous, Tilak was the most well-known Indian political leader. He was seen as a strong nationalist who wanted quick changes. The British government put him in prison several times because of his activism.

Joining the Indian National Congress

Tilak joined the Indian National Congress in 1890. He felt that the Congress was too slow and polite in asking for self-government. He was one of the most outspoken leaders at that time. Because of different ideas, the Congress later split into two groups: the Moderates and the Extremists.

In 1896, a serious plague spread in Pune. The British government took very strict actions to control it. These actions made many Indian people angry. Tilak wrote articles in his newspaper, Kesari, speaking up for the people. He was later put in prison for 18 months for his writings. When he came out, people saw him as a hero. He then used the famous slogan: "Swaraj (self-rule) is my birthright and I shall have it."

After the Partition of Bengal in 1905, which aimed to weaken the nationalist movement, Tilak strongly supported the Swadeshi movement. This movement encouraged Indians to use goods made in India and boycott foreign goods. Tilak believed that these two ideas went hand-in-hand.

Tilak had different views from leaders like Gopal Krishna Gokhale. He was supported by Bipin Chandra Pal and Lala Lajpat Rai. These three were famously called the "Lal-Bal-Pal triumvirate". In 1907, the Congress Party meeting in Surat saw a big disagreement. The party split into two groups: Tilak's radical group and the moderate group.

Tilak was the first Congress leader to suggest that Hindi written in the Devanagari script should be India's national language.

Challenges from the British Government

During his life, the British government tried to silence Tilak three times with charges related to his speeches and writings. In 1897, he was sent to prison for 18 months. In 1909, he was again charged and sentenced to six years in prison in Burma. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a lawyer, defended him in court. In 1916, Tilak was charged a third time for his speeches on self-rule. Again, Jinnah was his lawyer, and this time Tilak was found not guilty.

Time in Mandalay Prison

In 1908, Tilak wrote articles in his newspaper Kesari supporting revolutionaries and calling for immediate self-rule. The government quickly charged him. He was sentenced to six years in prison in Mandalay, Burma. While in prison from 1908 to 1914, he continued to read and write. He wrote an important book called Gita Rahasya. Many copies of this book were sold, and the money helped the Indian Independence movement.

Life After Prison

Tilak developed diabetes during his time in Mandalay prison. When he was released in 1914, he was eager to work with the Indian National Congress again. He rejoined the Congress in 1916.

Tilak tried to convince Mohandas Gandhi to consider all ways to achieve self-rule, not just complete non-violence. Gandhi respected Tilak's dedication and courage. When Tilak faced financial difficulties, Gandhi even asked Indians to donate money to help him.

All India Home Rule League

Tilak helped start the All India Home Rule League between 1916 and 1918, along with Annie Besant. This league aimed for self-rule for India. Tilak traveled to many villages, asking farmers and local people to join the movement. The league grew quickly, showing how many people supported the idea of self-rule. Tilak's league was active in Maharashtra, Central Provinces, and Karnataka.

Tilak's Ideas

Views on Religion and Politics

Tilak wanted to unite all Indians for political action against British rule. He believed that ancient Indian texts like the Ramayana and the Bhagavad Gita could inspire people to act. He called this idea karma-yoga, or the yoga of action. He believed the Bhagavad Gita encouraged people to do their duty and fight for what is right. He wrote his own interpretations of these texts to support his views.

Social Views

Tilak had some traditional views on social matters. He did not support some liberal changes happening in Pune, like women's rights or reforms against untouchability. He believed women should focus on their homes and families. In 1918, he did not sign a petition to end untouchability, even though he had spoken against it earlier.

Respect for Swami Vivekananda

Tilak and Swami Vivekananda had great respect for each other. They met in 1892 and Vivekananda even stayed as a guest at Tilak's house. It is said they agreed that Tilak would work for nationalism in politics, while Vivekananda would work for it in religion. When Vivekananda passed away young, Tilak expressed great sadness in his newspaper.

Contributions to Society

Tilak started two weekly newspapers in 1880–1881: Kesari in Marathi and Mahratta in English. Through these papers, he became known as an "awakener of India". Kesari later became a daily newspaper and is still published today.

In 1894, Tilak changed the private worship of Ganesha into a big public festival (Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav). These celebrations included processions, music, and food, and were organized by local communities. Students often used these events to celebrate Indian pride and discuss political issues, like supporting Swadeshi goods. In 1895, Tilak also started celebrating "Shiv Jayanti", the birth anniversary of Shivaji, the founder of the Maratha Empire. He also worked to raise money to rebuild Shivaji's tomb at Raigad Fort.

Tilak used festivals like Ganapati and Shiv Jayanti to build a strong national spirit among all Indians, not just the educated. This helped people unite against British rule.

The Deccan Education Society that Tilak helped found still runs important schools and colleges in Pune today, like Fergusson College. The Swadeshi movement he started became a key part of India's independence struggle. Tilak once said, "I regard India as my Motherland and my Goddess... loyal and steadfast work for their political and social emancipation is my highest religion and duty".

Books Written by Tilak

In 1903, Tilak wrote The Arctic Home in the Vedas. In this book, he suggested that the ancient Vedas might have been created in the Arctic region. He also wrote The Orion, where he tried to figure out the age of the Vedas using the positions of stars. While in Mandalay prison, he wrote Shrimadh Bhagvad Gita Rahasya, which is an analysis of Karma Yoga from the Bhagavad Gita.

Tilak's Family Legacy

Tilak's son, Shridhar Balwant Tilak, worked to end untouchability in the late 1920s with dalit leader Dr. Ambedkar. Shridhar's son, Jayantrao Tilak, was the editor of the Kesari newspaper for many years. Jayantrao was also a politician and served in the Indian Parliament. Rohit Tilak, another descendant, is also a politician today.

Legacy and Recognition

On 28 July 1956, a portrait of B. G. Tilak was placed in the Central Hall of Parliament House. The then Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, unveiled it.

Tilak Smarak Ranga Mandir, a theater in Pune, is named after him. In 2007, the Government of India released a special coin to celebrate Tilak's 150th birth anniversary. A classroom and lecture hall were also built in Mandalay prison as a memorial to him.

Several Indian films have been made about his life, including documentaries and feature films like Lokmanya: Ek Yugpurush (2015).

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Bal Gangadhar Tilak para niños

In Spanish: Bal Gangadhar Tilak para niños

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |