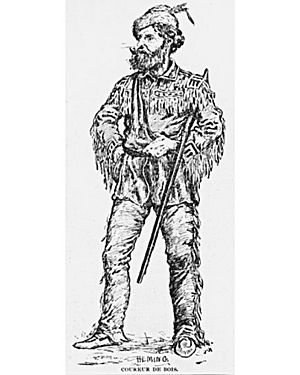

Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont facts for kids

Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont (born April 1679 – died 1734) was a French explorer. He explored and mapped the Missouri and Platte rivers in North America in the early 1700s. He wrote about his travels, describing the Native American tribes he met. In 1723, he built Fort Orleans, the first European fort on the Missouri River. It was near what is now Brunswick, Missouri. In 1724, he led a trip to the Great Plains in Kansas to set up trade with the Padouca, who were Apache Indians.

Contents

Bourgmont's Early Life in France

Étienne de Bourgmont was born in Cerisy-Belle-Étoile in Normandy, France. When he was 19, in 1698, he had a legal problem related to hunting on monastery land. He did not pay a fine. Because of this, he likely left France for New France (North America) that same year. He wanted to avoid being put in prison.

Adventures in North America

In 1702, Bourgmont was with French Marines in Canada. They were trying to set up a place to make leather from buffalo hides. This place was at the mouth of the Ouabache River (Wabash River) on the Ohio River. The business closed in 1703, and Bourgmont moved to Quebec.

Commanding Fort Pontchartrain

In 1705, Bourgmont was sent to Fort Pontchartrain in what is now Detroit, Michigan. He took command of the fort in 1706. In March 1706, a group of Ottawa people attacked some Miami people outside the fort. Soldiers from the fort fired their weapons. Sadly, a French priest and a sergeant, who were outside the walls, were killed. About 30 Ottawa people also died. Bourgmont was criticized for how he handled this event. When the leader, Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac, visited in August, Bourgmont and others had left their posts.

In 1712, Bourgmont returned to Fort Pontchartrain. He helped the Algonquian, Missouria, and Osage tribes fight against the Fox tribe. Even though he had left his post before, he traveled widely. Around 1713, Cadillac seemed to forgive him. This was because Bourgmont knew a lot about the Native American tribes and the land. This knowledge was very helpful to the French.

Bourgmont's Family Life

Bourgmont had a relationship with a woman known as Madame Tichenet, or "La Chenette," at Fort Pontchartrain. After he left his post in 1706, they lived together for a time. La Chenette was the daughter of a French man and a Native American woman. They later separated.

In 1712, Bourgmont met the daughter of the chief of the Missouria tribe. He went with her to the Missouria village near the Grand River in Missouri. He lived there for a long time and built close relationships with the Missouria people. He had children with her, including a son born around 1714. In 1713, Bourgmont and other traders, who also had Native American wives, visited Illinois. Some French officials were not happy about this. Another order for his arrest came from Paris, but Cadillac did not act on it.

In May 1721, Bourgmont returned to Paris. He received honors for his explorations and reports. He then married Jacqueline Bouvet des Bordeaux in his home village in Normandy. He left in June to go back to New Orleans.

In 1724, Bourgmont led a group of soldiers into Pawnee territory. He set up a fur trading post on the Niobrara River. He talked with the Pawnee people. Bourgmont promised the Pawnee that France would not be allies with the Sioux, who lived north of the Niobrara River. However, the Pawnee found out Bourgmont had not told them the truth. They attacked the trading post. When Bourgmont returned, the post was burned, and the soldiers he left there were gone. An attempt to rescue them led to a shootout. Two French soldiers were saved, but eight others had been killed.

Bourgmont and his remaining men tried to return to the Missouri River. On their way, a group of 16 men sent ahead were killed. Later, another Pawnee war party ambushed them. Most of Bourgmont's men were killed. However, Bourgmont and 11 others made it back to Fort Orleans. They were in very bad condition. Bourgmont later returned to France.

In 1725, Bourgmont took a group of four Native American leaders from the Illinois, Missouria, Osage, and Oto tribes to visit France. His Missouria wife also went with them. While in France, Bourgmont's Missouria wife was baptized and married to his close friend, Sergeant Dubois. Dubois and his new wife returned to North America with the other Native Americans. Bourgmont stayed in France with his French wife, Jacqueline. Sergeant Dubois was later killed by Native Americans. The Missouria woman then married a militia captain. She was still alive in 1752. The last record of Bourgmont's Missouria son was in 1724.

Bourgmont and his French wife, Jacqueline, had four children. All of them died young. In 1728, another woman, Marie Angelique, who was Bourgmont's "Padouca slave," was baptized in Cérisy. Four years later, in 1732, she got married. She had a six-week-old son who was made legitimate by the wedding.

Becoming a French Hero

In 1713, Bourgmont started writing a book called Exact Description of Louisiana. It described its harbors, lands, rivers, and Native American tribes. It also talked about trade and how to set up a colony. In March 1714, he traveled to the mouth of the Platte River. He named it the Rivière Nebraskier, which means "flat water" in the Otoe tribe language. He also wrote The Route to Be Taken to Ascend the Missouri River. This report was the first detailed account of travels so far north on the Missouri River.

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, who replaced Cadillac, suggested that Bourgmont receive the Order of Saint Louis. This was a high honor for his service to France. It recognized his explorations and detailed reports of river travel. In September 1719, the Council of the Colony of Louisiana also praised Bourgmont for his work with Native Americans.

Native American tribes valued the goods Bourgmont traded, such as gunpowder, guns, kettles, and blankets. The Spanish, on the other hand, traded fewer horses, knives, and "inferior axes."

French officials asked Bourgmont to bring chiefs from several tribes to Dauphin Island. This was a French base in what is now Alabama. Most of the chiefs died on the way. Bourgmont took the surviving chief back home. He then returned to the new settlement of New Orleans. He was paid a large sum of money for his work.

In June 1720, Bourgmont and his Métis son traveled to Paris. They were welcomed as heroes. News had arrived that Native American tribes friendly to Bourgmont had defeated the Spanish Villasur expedition. In July, Bourgmont became a captain in the French army. In August 1720, he was named "Commandant of the Missouri River." He was asked to build a fort on the Missouri River. He also had to negotiate with tribes to allow peaceful French trade. In return, he would receive noble status.

Journey to the Great Plains

Bourgmont built Fort Orleans in early 1723. It became the main military base for the Missouri River area. From Fort Orleans, he planned to visit the Padouca people on the Great Plains. He also wanted to open a trade route to the Spanish colony in New Mexico. Bourgmont asked the Kaw people for help with his trip.

He sent 22 Frenchmen and Canadians by boat from Fort Orleans to the Kaw village. This village was near Doniphan, Kansas. They carried supplies and gifts. Bourgmont traveled by land with 10 French colonists, 100 Missouria, and 64 Osage people. Bourgmont's visit to the Kaw was the first official French visit. However, many French traders, including Bourgmont himself, had visited them before. Some Kaw people had also traveled to trade in Kaskaskia, Illinois, a French village.

Meeting the Kaw People

Bourgmont's group reached the Kaw village on July 8, 1724. It was a large village with at least 1,500 people. The Kaw welcomed him as an old friend. They honored him with many speeches and feasts. When they talked about trade, the Kaw were tough negotiators. Bourgmont wanted to buy horses from them. The Kaw only had five horses to trade, and they asked for a high price. This shows that horses were still rare on the eastern edge of the Plains. The Kaw also traded six slaves (likely Native Americans from other tribes captured in battles), food, furs, and animal skins. On July 24, Bourgmont, his French, Missouria, and Osage group, and most of the Kaw left to visit the Padouca.

Reaching the Padouca

Because of the heat, Bourgmont became sick. The entire group of over 1,000 people returned to the Kaw village. Bourgmont sent a messenger to contact the Padouca. He told them he would come soon and would bring two Padouca slaves back to their tribe as a sign of friendship. Bourgmont's messenger found the Padouca in western Kansas. They were likely in the El Cuartelejo region in Scott County. This area had become a safe place for Native Americans escaping the Spanish in New Mexico. Eight villages with about 600 men lived there. They agreed to move closer to the Kaw village to meet Bourgmont. Five Padouca people returned to the Kaw village to be guides.

After recovering from his illness, Bourgmont continued his journey to the Padouca on October 8. His group was much smaller: 15 French and Métis people, including Bourgmont's son; the five Padouca guides, seven Missouria, five Kaw, four Otoe, and three Iowa. The Osage were not part of this smaller trip. Ten horses carried their supplies. The group traveled southwest. On October 11, at the Kansas River crossing near Rossville, Bourgmont saw many buffalo. The expedition passed through countless buffalo herds. They saw 30 herds in one day, each with 400-500 buffalo. Bourgmont wrote, "Our hunters kill as many as they please." Deer were also plentiful. In one day, they saw over 200 deer, plus many turkeys near the streams.

Meeting the Padouca People

On October 18, Bourgmont met the Padouca. Eighty Padouca people rode out on horses to meet the French. They took them back to their camp. The large number of horses showed that the Padouca had more horses than the Kaw and other tribes further east. Historians have debated who these Padouca people were. The French later called the Comanche people "Padouca." However, most historians now believe Bourgmont's Padouca were likely the Apache Indians.

Bourgmont received a great welcome. He, his son, and two other French explorers were seated on a buffalo robe. They were carried to the Padouca chief's tent for a large feast. The next day, Bourgmont gathered his trade goods and divided them into groups.

The Padouca (or Apache) had never seen such a variety of European goods. They were scared of the guns.

Bourgmont gathered 200 Apache chiefs. He talked about the need for peace among all tribes. He asked them to let French traders pass through their lands on the way to Spanish settlements in New Mexico. Then, he invited the chiefs to take what they wanted from the goods.

He estimated that the village had 140 homes. There were about 800 men, over 1,500 women, and about 2,000 children. The chief said he controlled twelve villages. Together, they had about 16,000 people. The Apache lived in a large area, stretching over 520 miles.

Bourgmont wrote that the Apache had permanent villages. They sent out hunting parties of 50-100 families. As one group returned, another would leave, so the village was always occupied. They traveled up to five or six days from their village to hunt. The Apache grew a little corn and pumpkins. They got tobacco and horses by trading with the Spanish in New Mexico. In return, they traded tanned buffalo skins. It is unclear if the Spanish visited the Apache villages or if the Apaches traveled to Spanish settlements. The latter seems more likely. Bourgmont noticed that Apache people living furthest from Spanish settlements still used flint knives for skinning buffalo and cutting trees. This showed that not much European trade had reached them.

The Apache were welcoming. They feasted Bourgmont and his group for three days. On October 22, the French party started their journey home. By October 31, Bourgmont had reached the Kaw village again. Traveling down the Missouri River in round "bullboats" (made of buffalo hides over wood frames), the group reached Fort Orleans on November 5. Bourgmont thought his trip was successful. However, not much came of it. Within about ten years, the Apache he met in Kansas were gone. They were pushed south by the Comanche tribe, who were migrating from the Rocky Mountains.

Where the Padouca Lived

Experts studying old documents and maps believe the Apache village was probably on the Little Arkansas River near Lyons, Kansas. This is the same place where Francisco Vásquez de Coronado found Quivira 173 years earlier. Coronado was looking for tribes with gold. However, the Wichita Indians, whom Coronado met in Quivira, were no longer there. It seems the Apache had pushed them south and east. In turn, the Comanche would later push the Apache south.

Return to France

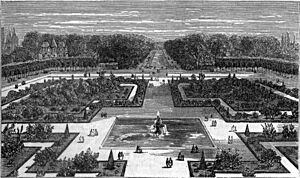

In 1725, Bourgmont was allowed to invite and travel with Native American representatives to Paris. The chiefs were shown the amazing power of France. They visited the Versailles, Château de Marly, and Fontainebleau. They hunted in the royal forest with Louis XV and saw an opera. Bourgmont's Missouria wife was officially listed as a servant.

In late 1725, the tribal leaders and his Missouria wife returned to North America. Bourgmont stayed in Normandy with his French wife. He had been given the title of écuyer (squire).

The French government did not continue to support Fort Orleans, and it was left empty in 1726. Bourgmont died in France in 1734.

See also

In Spanish: Étienne de Veniard para niños

In Spanish: Étienne de Veniard para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |