Cow Creek (Montana) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Cow Creek |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| country | United States |

| state | Montana |

| county | Blaine |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Bear Paw Mountains 48°05′28″N 109°20′07″W / 48.09111°N 109.33528°W |

| River mouth | Missouri River 47°47′15″N 108°56′10″W / 47.78750°N 108.93611°W |

| Length | 35 miles (56 km) |

Cow Creek is a small river, about 35 miles (56 km) long, in north central Montana, United States. It flows into the Missouri River. Cow Creek starts in the southern part of the Bears Paw Mountains in Blaine County. It flows east, then south, joining the Missouri River about 25 air miles (40 km) northeast of Winifred, Montana. This spot is also about 22 miles (35 km) upstream from the Fred Robinson Bridge.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The Gros Ventre people, who lived in this area, called the creek báasikɔ́hʔɔ́wuh. This name means 'big gulch' in their language.

A Look Back in Time

Ancient History of Cow Creek

Cow Creek flows from the southern foothills of the Bears Paw Mountains into the Missouri River. This area is known as the Missouri Breaks. The Breaks are a wild and rugged landscape with many steep hills and eroded lands. They are so rough that it's hard for animals or people to travel through them.

The Missouri Breaks stretch for over 200 miles (320 km) along the Missouri River. They make it difficult to reach the river from the wide grasslands to the north and south. Cow Creek is special because it offers one of the few ways to get down to the Missouri River through these tough Breaks.

As Cow Creek winds through the Breaks, it flows between high, canyon-like walls. But the bottom of the canyon is fairly flat and wide, from 100 to 600 yards (91–549 m). This flat area created a natural path for travel.

Over time, dirt and sand washed out from the mouth of Cow Creek into the Missouri River. This formed a small piece of land called Cow Island, just downstream from where the creek meets the river. Cow Island splits the Missouri River into two channels, making it easier to cross the wide river here. On the south side of the river, opposite Cow Island, there's a steep but short 4 miles (6.4 km) climb out of the Breaks. This leads to the wide plains of Central Montana.

Because of these features, Cow Creek and the crossing at Cow Island became an important travel route for thousands of years. Buffalo herds and other animals used it for migration. Native American tribes also used this "highway" to move between the plains north and south of the Missouri River Breaks.

Lewis and Clark's Journey

The famous explorers Lewis and Clark passed by Cow Creek on May 26, 1805. They had camped two miles below the creek the night before. In their journals, they first called it Windsor Creek, after a soldier named Pvt. Richard Windsor. Later, fur traders renamed it Cow Creek.

On that same day, May 26, 1805, William Clark climbed out of the Breaks. He likely went up a nearby creek called Bull Whacker Creek to reach a ridge. From there, he saw the Rocky Mountains for the very first time. When Meriwether Lewis noted Cow Creek, he reported it was 30 yards (27 m) wide. This means it was likely in its spring flood stage. Normally, Cow Creek is only a few yards wide. In very dry weather, it can even become just a trickle between small pools of water.

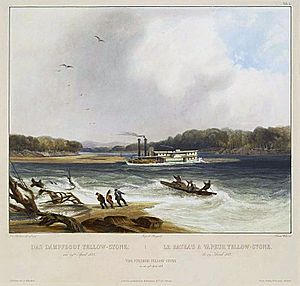

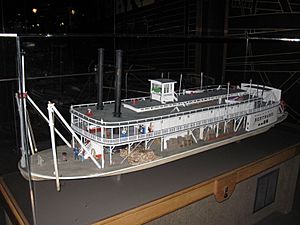

Steamboat Days

The spot where Cow Creek meets the Missouri River became a busy steamboat stop called Cow Island Landing. This happened mostly in late summer and fall. During these months, the Missouri River's water level would drop. This made it hard for steamboats to get past a series of rapids upstream from Cow Island. These rapids included Bird Rapids, Cabin Rapids, Dauphine Rapids, and Deadman Rapids.

Since Cow Island Landing was about 126 miles (203 km) short of Fort Benton, steamboats had to unload their goods here. The cargo was then moved by wagons along the Cow Island Trail.

After gold was found in the Montana Territory in 1862, the Missouri River became the best way to bring people and supplies to the busy gold fields. From the 1860s to the mid-1880s, steamboats carried goods about 2,600 miles (4,200 km) from places like St. Louis to Fort Benton.

The last 1,300 miles (2,100 km) of the river was called the "upper Missouri." This part of the river went through remote, unsettled plains and the Missouri Breaks. In May and June, snow melting from the mountains caused "high water" in the Missouri River. Steamboats could use this high water to travel all the way to Fort Benton. But later in summer and fall, water levels dropped. This "low water" meant that larger steamboats often couldn't reach Fort Benton. They had to unload their cargo further downstream in the Missouri Breaks.

Every year during the steamboat era, if the water wasn't deep enough, Cow Island Landing became a busy river port. It was the best place to unload freight and transport it overland to Fort Benton using the Cow Island Trail.

To unload cargo, steamboats used landing spots a few hundred yards upstream or downstream from Cow Creek. They chose places where the river was deep close to the north bank. This allowed the boats to pull in close to the shore to unload their goods.

The Cow Island Trail

The wagon road that started at Cow Island Landing and went up Cow Creek to the plains and then to Fort Benton was known as the Cow Island Trail.

This road was the only possible route for wagons in this rough area of the Missouri Breaks. Cow Creek is 35 miles (56 km) long, making it one of the longer rivers in the Breaks that flows into the Missouri. Over thousands of years, seasonal snowmelt widened the creek bottom. This made it flat enough for wagons to travel.

From the steamboat landing, the trail went north up the Cow Creek valley for 15 miles (24 km) to Davidson Coulee. There, the trail turned west and climbed a long, steep hill called Davidson Ridge. This led to the plains north of the Missouri River Breaks.

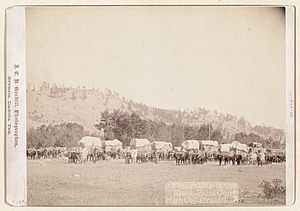

The amount of freight on the Cow Island Trail changed a lot. It depended on whether the riverboats could reach Fort Benton (high water) or had to unload at Cow Island Landing (low water). In 1863, a low-water year, the trail saw a lot of traffic. News of rich gold discoveries in Montana Territory was spreading. By 1868, about 2,500 men, 3,000 teams, and 20,000 oxen were involved in moving freight on the Cow Island Trail to Fort Benton.

No permanent buildings were built at Cow Island to store goods. Once freight was unloaded, it was covered with tarps and quickly moved to Fort Benton. The biggest profits were made only when the goods reached Fort Benton. A common setup for freighting was two wagons, each pulled by six to eight oxen, with two drivers. Oxen were preferred over horses and mules. They needed less food and water, didn't wander off in storms, and Native Americans didn't steal them because they couldn't be ridden and were too tough to eat.

The Cow Creek Trail was not easy. Carrying freight to Fort Benton was always a challenge. In the narrow but flat bottom of Cow Creek, the creek twisted back and forth. Wagons had to cross Cow Creek 31 times over 15 miles (24 km). These crossings could wash out after heavy rain. In wet weather, heavy wagons could get stuck. After 15 miles (24 km) up the creek, freighters faced long, steep hills. They often had to unhitch and use "double teams" or even "triple teams" of oxen to pull each wagon up. In 1864, a wagon went off the trail on a steep hill, dragging its oxen with it. They fell 300 feet (91 m), killing the oxen and damaging the wagon.

The Nez Perce War

On September 23, 1877, several hundred Nez Perce people crossed the Missouri River at Cow Creek. They were trying to reach Canada to find safety. An army group of twelve soldiers, led by Sergeant William Molchert, was at Cow Island Landing. Four civilian clerks, who worked for freight companies, were also there. Fifty tons of supplies, unloaded from steamboats, were waiting to be shipped to Fort Benton.

The Nez Perce crossed the Missouri in different groups. First, about 20 warriors crossed and spread out on the north bank. Then, the women and children crossed with their animals and camp gear. Finally, a group of warriors crossed as a rear guard.

Several small fights involving the Nez Perce happened on Cow Creek. But the most important event was a decision made while they were camped on Cow Creek on September 25, 1877.

The soldiers at Cow Island Landing were there to guard the supplies. When the Nez Perce arrived, the soldiers and clerks went into a small earthen fort they had built. This fort was a few hundred yards from the river crossing and also a few hundred yards from the stacked supplies.

After crossing the river, most of the Nez Perce passed the soldiers without trouble and camped about two miles up Cow Creek. A small group of Nez Perce went to the fort. They seemed friendly and asked for some food from the supplies. The army sergeant in charge at first ignored them. Finally, he gave them one bag of hardtack and one side of bacon from the soldiers' own food.

At sunset, gunfire started from some Nez Perce in the Breaks. They had found positions where they could shoot down into the fort. Two civilians were wounded, and the soldiers were pinned down. The supplies were far enough from the fort that, as night fell, the Nez Perce could reach them without being shot at. After dark, the Nez Perce took what they wanted from the supplies and set the rest on fire. A large pile of bacon burned brightly for most of the night. The soldiers thought this light stopped a bigger attack. However, it's more likely the Nez Perce only wanted the supplies, not a big battle. The Nez Perce and soldiers exchanged occasional gunfire through the night until about 10:00 AM. Then, the Nez Perce moved further up Cow Creek. Two civilians and one Nez Perce warrior were wounded in this encounter.

On September 22, 1877, before the Nez Perce arrived, a wagon train had left Cow Island Landing. It carried 35 tons[convert: unknown unit] of freight and a herd of cattle, heading up the Cow Island Trail to Fort Benton. On September 24, while still in Cow Creek Canyon, the Nez Perce caught up to the wagon train. They approached peacefully and camped about one and a half miles away. That evening, some Nez Perce visited the wagon train's camp. They had friendly talks and wanted to trade for ammunition and other goods.

On the morning of September 25, a small army relief force, led by Major Guido Igles, approached the Nez Perce from behind. Major Igles had come from Fort Benton to help the outpost at Cow Island Landing. He was leading a few soldiers and civilian volunteers. After reaching Cow Island on September 24, he continued to follow the Nez Perce.

When the Nez Perce saw Major Igles coming up Cow Creek, some warriors went down the canyon to prepare for a fight. Other Nez Perce attacked the wagon train. One teamster lost his life, and the others ran into the bushes along the creek or into the Breaks. The main group of Nez Perce took some goods from the wagons, set them on fire, and continued up Cow Creek.

Meanwhile, the Nez Perce warriors who were the rear guard had taken positions on high ground facing Major Igles' small force. Igles' group was down in Cow Creek canyon. Firing began. The Nez Perce were in a good position to shoot down at Igles' group. One civilian was killed. Another was saved when a bullet hit his belt buckle, bruising him. After two hours, the Nez Perce stopped fighting. Major Igles feared an ambush and knew he was greatly outnumbered. He began a slow and careful retreat back to Cow Island Landing. He reported that two Nez Perce were wounded in this fight.

On the night of September 25, the steamboat Benton arrived at Cow Island Landing, unloading fifty tons of freight. Another steamboat, the Silver City, was approaching with one hundred more tons. Major Igles sent messengers to General Miles, telling him where the Nez Perce were. General Miles was coming across the country from Fort Keogh with fresh troops to stop the Nez Perce.

When the Nez Perce started up Cow Creek, they were only 80 miles (130 km) from Canada. While camped on Cow Creek on the evening of September 25, after the fight with Major Igles, the Nez Perce leaders disagreed. Some wanted to keep going quickly, while others wanted to rest their tired people and horses. The Nez Perce believed the soldiers were far behind them. They didn't know that General Miles was coming fast with his troops. Those who wanted to go slower won the argument.

Because the Nez Perce paused instead of pushing ahead, General Miles' column caught up to them on September 30. The Nez Perce were camped on Snake Creek, east of the Bear Paw Mountains, just 40 miles (64 km) from Canada. Miles attacked right away. On October 5, 1877, after six days of fighting in freezing weather, Chief Joseph surrendered the Nez Perce to the U.S. Army commanders. Many Nez Perce men, women, and children had suffered from wounds and the cold.

The Nez Perce were captured because they delayed crossing into Canada. This allowed General Miles to catch up with a larger, stronger army. The events and small fights on Cow Creek added to this delay. However, the most important reason for their capture was the decision made during the tribal council on the evening of September 25, 1877, while they were camped along Cow Creek.

Early Settlers (Homesteading)

Where small creeks flow from the Breaks into the Missouri River, there are wide, flat areas along the river. These "bottoms" have meadows and cottonwood trees. Cow Creek opens into such a bottom where it meets the Missouri. Further downstream, Bull Creek also has a similar bottom.

Just upstream from the mouth of Cow Creek is the Kipp homestead. It's next to the old upper steamboat landing. Some say this homestead was first claimed by James Kipp (1788–1880), a historical figure. His son Joseph and grandson James Kipp then lived there. This Kipp homestead and another one on Bull Creek later became property of the Jones family, who were related to the Kipps by marriage. Another source says Jim Kipp, Joseph's son, claimed the homestead in 1913. The elder James Kipp (1788–1880) helped create Fort Union in 1828 and Fort Piegan in 1831. The Kipp homestead is now abandoned, but a few cabins and other buildings still stand there.

Just downstream from Cow Creek's mouth is Bull Creek. Here, on Bull Creek bottom, is another abandoned homestead. It has crumbling log buildings and old farm equipment. This homestead is believed to have belonged to the Jones family, who were related to the Kipp family.

A basic road used to connect these homesteads. It ran downstream along the Missouri River's north side to a power plant site. This road was still usable a few years ago. During the homesteading years, one of the few ferries in the Missouri Breaks operated at the power plant site. From this ferry, roads went north to the Zortman area and south toward Lewistown, Montana.

Cow Creek Today

Cow Creek and the Cow Island Crossing were once important travel routes for animals and Native Americans. Today, they are quiet and unused. The large buffalo herds were nearly hunted to extinction. Native American tribes were moved to reservations, far from Cow Creek. Railroads ended the need for Missouri River steamboats. Many homesteaders in the Missouri Breaks gave up and left. New highways were built in easier locations, not through Cow Island or Cow Creek. A few ranches still exist along the upper part of Cow Creek, near the Bear Paw Mountains.

Cow Creek is now one of the most remote and empty places in the Missouri Breaks, an area already known for its isolation. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) recognizes this. They are currently thinking about giving the lower part of Cow Creek "wilderness status." This would protect its natural state.

The abandoned buildings of the Kipp homestead and the homestead on Bull Creek continue to fall apart. For many years, a "snubbing post" (used to tie up steamboats) was buried in the river bank near the Kipp homestead. It might have washed into the river by now. People say that the remains of the earthen fort used by soldiers in the 1877 fight with the Nez Perce (known as the "Battle of Cow Island") are still visible. For many years, metal pieces from wagons burned by the Nez Perce on September 25, 1877, could be seen in Cow Creek canyon.

There's a local rumor that the wagon train carried gold, and the Nez Perce took it and buried it nearby. However, this story is very likely not true.

The lower part of Cow Creek, where the deserted homesteads are, is hard to visit. A mostly dirt road managed by the BLM runs west from Montana Highway 66 for 14 miles (23 km). It then drops down into Bull Creek. Bull Creek meets the Missouri very close to Cow Island. From Bull Creek, you can reach the nearby mouth of Cow Creek. This road, as it goes down from the high ridges of the Breaks into the Missouri bottom at Bull Creek, has steep, bumpy slopes and many sharp turns. The road is often cut into the side of steep cliffs. It's badly eroded with washouts, and there are very few places to turn around if you decide to go back.

As for the old freight trail that went upstream from the mouth of Cow Creek, there isn't really a road for the first 15 miles (24 km) anymore. The many creek crossings of the old Cow Creek trail have been washed away. The gravel bars where wagons crossed have been swept downstream. You can still see parts of the old Cow Creek Trail here and there, but it's not continuous.

Upper Cow Creek is not as isolated. About 15 miles (24 km) up from the Missouri, where Davidson Coulee flows into Cow Creek, Blaine County Road 330 (Cow Creek Trail) drops down Davidson Ridge to Cow Creek Bottom from the west. One ranch is located near this point. The name "Cow Island Trail" is still used for the road that goes from the meeting point of Cow Creek and Davidson Coulee up to the flat land and then west. This is probably the same route the original Cow Island freight trail followed to Fort Benton. Above Davidson Coulee, Cow Creek runs next to Blaine County Road 314 (Birdtail Road) for about 6 miles (10 km). In the upper parts of Cow Creek, another County road (Birdtail Road) goes down to a second ranch. Blaine County Road 300 crosses Cow Creek at its very top, near where West and East Cow Creek meet, just below the southern side of the Bears Paw Mountains.

Most roads in the Breaks are just dirt roads. Only a few have gravel. Dirt roads in the Cow Creek area (and most of the Missouri Breaks) are very difficult or impossible to travel on when wet. The Breaks are partly made of clay from old rock formations that contain bentonite. When this clay gets wet, it becomes slippery and turns into "gumbo." This sticky mud clings to and builds up on tires, wheels, feet, and hooves. If you get caught on a dirt road in the Breaks during rain, the best (and sometimes only) thing to do is wait until the surface dries out.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |