History of agriculture in the United States facts for kids

The history of farming in the United States tells the story of how agriculture has changed from the first English settlers until today. In the early days of Colonial America, farming was the main way of life for most people. About 90% of the population were farmers. Most towns were places where farm products were shipped out to other countries.

Most farms grew just enough food for the family to eat. As more people arrived and the country grew westward, many new farms were started. Clearing land for farming was a big job for farmers. After 1800, cotton became the most important crop in the southern plantations. It was also the main product America sold to other countries.

After 1840, new factories and growing cities created good markets for farm products within the country. The number of farms grew a lot. There were 1.4 million farms in 1850, 4.0 million in 1880, and 6.4 million in 1910. Then, the number of farms started to go down. It dropped to 5.6 million in 1950 and 2.2 million in 2008.

Contents

- Early American Farming: Before Europeans Arrived

- Colonial Farming: 1610–1775

- A New Nation: 1776–1860

- The Railroad Age: 1860–1910

- Farming in the South: 1860–1940

- The Grange: Helping Farmers Unite

- World War I and Farming

- The 1920s: Changes on the Farm

- The 1930s: The Great Depression and New Deal

- Farming from 1945 to Today

- Important Crops in U.S. History

Early American Farming: Before Europeans Arrived

Before Europeans came to North America, many different groups of Native Americans lived there. Some groups hunted animals and gathered plants for food. Others grew their own food. Native Americans farmed crops in the Eastern Woodlands, the Great Plains, and the American Southwest.

Colonial Farming: 1610–1775

The first settlers in Plymouth Colony tried planting barley and peas from England. But their most important crop was Indian corn, also known as maize. Native Americans like Squanto taught them how to grow it. To make the soil better for corn, they used small fish like herrings or shad as fertilizer.

Large farms called plantations grew in places like Virginia and Maryland. These farms used enslaved people to grow crops like tobacco. In South Carolina, they grew indigo (a plant for dye) and rice. After 1800, cotton became a major plantation crop in the "Black Belt" region. This area stretched from North Carolina through Texas, where the climate was good for growing cotton.

Most farms during the colonial period were small, family farms. They grew food for the family and some extra to trade or sell. Farmers also made money by selling extra crops or animals in local markets. Some products were even sent to the slave colonies in the British West Indies. Cutting down trees, hunting, and fishing also helped families make a living.

How Different Groups Farmed

Different groups of settlers had their own ways of farming. German Americans brought farming traditions from Europe. They changed their old ways to fit the new, more plentiful land in America. Germans often kept their farms in the family for many generations. They also preferred using oxen instead of horses for plowing.

Scots Irish settlers focused on mixed farming. They grew corn for people and for feeding animals, especially hogs. Many farmers, no matter their background, started using new methods to grow more food. In the 1750s, farmers began using the cradle scythe to harvest hay, wheat, and barley. This tool had wooden fingers that helped gather the grain. It allowed a farmer to do three times more work in a day. Some wealthy farmers, like George Washington, even started using animal waste and lime to fertilize their fields. They also rotated their crops to keep the soil healthy.

Before 1720, most colonists in the mid-Atlantic region were small farmers. They sold corn and flour to the West Indies to pay for goods from Europe. In New York, selling fur to Europe also brought in money. After 1720, the demand for wheat in Europe grew, which helped mid-Atlantic farmers. By 1770, a bushel of wheat cost twice as much as it did in 1720. Farmers also grew more flaxseed and corn because there was a high demand for flax in Ireland and corn in the West Indies.

Many poor German and Scots-Irish immigrants worked as farm laborers. Merchants and craftspeople hired young indentured servants. These servants worked to pay for their trip from Europe. They helped make cloth and other goods at home. Wealthy farmers and merchants became rich, while smaller farmers and craftspeople often only made enough to get by.

A New Nation: 1776–1860

In the early 1800s, the U.S. economy was mostly about farming. The country grew westward with the Louisiana Purchase and victory in the War of 1812. Building canals and using steamboats opened up new areas for farming. Most farms grew food for the family and sold a little to local markets. During times of fast economic growth, a farmer could improve their land and sell it for more than they paid. Then, they could move further west and do it again. While land was cheap and fertile, clearing it and building farms was hard work.

Farming in the South

In the Southern United States, poor white farmers often owned less fertile land and usually no enslaved people. The best lands were owned by rich plantation owners. These farms mostly used enslaved labor. They grew their own food but also focused on crops like cotton, tobacco, and sugar for sale in Europe. The cotton gin machine made it much easier to produce cotton. Cotton became the main export crop.

However, cotton quickly used up the soil's nutrients. So, plantation owners often bought new land further west and bought more enslaved people to work their new farms. Much land in the Mississippi valley and Alabama was cleared for cotton. New areas in the Midwest also started growing grain. This led to lower prices for crops, especially cotton, in the 1820s and 1840s. Sugar cane was grown in Louisiana and turned into sugar. Growing and refining sugar needed a lot of money. Some of the richest people in the country owned sugar plantations with their own sugar mills.

Farming in New England

In New England, small family farms changed after 1810. They started growing food to supply the fast-growing industrial towns and cities. New special crops like tobacco and cranberries were also introduced for export.

Moving West: The Frontier

After the American Revolutionary War, people began moving west of the Appalachian Mountains. This movement started in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina after 1781. Pioneers lived in simple lean-tos or one-room log cabins. At first, they hunted deer, turkeys, and other small animals for food.

Pioneers wore clothes made from leather and fur. They carried a hunting knife and a shot pouch. Soon, they cleared a patch of woods to grow corn, wheat, flax, tobacco, and even fruit. After a few years, they added hogs, sheep, cattle, and sometimes a horse. They started wearing clothes made from homespun fabric instead of animal skins. Some restless pioneers moved even further west, looking for new land.

In 1788, American pioneers founded Marietta, Ohio. It was the first permanent American settlement in the Northwest Territory. By 1813, the western frontier reached the Mississippi River. St. Louis, Missouri was the biggest town on the frontier. It was a main stop for westward travel and a big trading center for river traffic.

Everyone agreed that the new territories should be settled quickly. But there was a debate about how much the government should charge for land. Some wanted higher prices to help pay for the government. Others wanted very low prices for land. The Homestead Act of 1862 finally allowed settlers to get 160 acres of land for free if they worked on it for five years.

From the 1770s to the 1830s, pioneer families moved into new lands from Kentucky to Alabama to Texas. Many were farmers. The first pioneers sometimes didn't know how to farm the land well. When the soil lost its natural richness, they would sell their farms and move west to try again. They often didn't use grass seed for hay, so animals had to find food in the forests. They planted the same crop until the soil was used up and didn't put animal waste back into the fields. Their farming tools were simple. This is why pioneer farmers often kept moving. The second wave of settlers often improved the land and practiced better farming methods.

The Railroad Age: 1860–1910

Farming grew a lot between 1860 and 1910. The number of farms tripled from 2 million in 1860 to 6 million in 1906. The number of people living on farms also grew from about 10 million in 1860 to 31 million in 1905. The value of farms increased from $8 billion in 1860 to $30 billion in 1906. The Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902 helped fund projects to bring water to dry lands in 20 states.

The government gave 160-acre plots of land for very low prices to about 400,000 families through the Homestead Act of 1862. Even more people bought land cheaply from the new railroads. The railroads wanted to create markets for their services. They advertised a lot in Europe and brought hundreds of thousands of farmers from Germany, Scandinavia, and Britain to America at low fares. The early 1900s were good years for American farmers.

Life on the Farm

Early settlers on the Great Plains found that the land was not a desert. However, the weather was very harsh. There were tornadoes, blizzards, droughts, hail, floods, and grasshoppers. This meant a high risk of ruined crops. Many settlers lost all their money, especially in the early 1890s. Some joined the Populist movement to protest, and others moved back east. In the 1900s, crop insurance, new ways to protect the soil, and government help reduced these risks. Immigrants, especially Germans, were a large group of settlers after 1860. They were drawn by good soil and cheap land from railroad companies. Railroads offered attractive packages, bringing European families and their tools directly to new farms bought on easy credit.

Blowing dust was a problem because there wasn't enough rain to grow wheat and keep the topsoil from blowing away. In the 1930s, the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) taught farmers new ways to protect the soil. By 1940, with better weather, the soil condition improved a lot.

On the Great Plains, few single men tried to farm alone. Farmers knew they needed a hard-working wife and many children to help with chores. These chores included raising children, feeding and clothing the family, managing the house, feeding hired workers, and handling paperwork and money. In the late 1800s, farm women played a big part in helping their families survive by working outdoors. After a generation or so, women started working less in the fields. New things like sewing and washing machines encouraged women to focus more on household tasks. Ideas about "scientific housekeeping" were spread through media, government agents, county fairs, and home economics classes.

Even though farm life on the prairies could seem lonely, people created a rich social life. They often had activities that mixed work, food, and fun. These included barn raisings, corn huskings, quilting bees, Grange meetings, church events, and school functions. Women organized shared meals and visits between families.

Ranching in the West

Much of the Great Plains became open range. This meant cattle ranchers could use public land for free. In the spring and fall, ranchers held roundups. Cowboys branded new calves, treated animals, and sorted cattle for sale. This type of ranching started in Texas and moved north. Cowboys drove Texas cattle north to railroad lines in cities like Dodge City, Kansas and Ogallala, Nebraska. From there, cattle were shipped east.

British investors helped fund many large ranches. But too many cattle on the land and a terrible winter in 1886–87 caused a disaster. Many cattle starved or froze to death. After that, ranchers usually grew feed to keep their cattle alive during winter.

Where there wasn't enough rain for growing crops, but enough grass for grazing, cattle ranching became popular. Before railroads reached Texas in the 1870s, cattle drives moved large herds from Texas to the railheads in Kansas. A few thousand Sioux and other Native Americans resisted, but most became ranch hands and cowboys themselves. New types of wheat grew well in the dry parts of the Great Plains, opening up areas like the Dakotas, Montana, western Kansas, and eastern Colorado. Where it was too dry for wheat, settlers turned to cattle ranching.

Farming in the South: 1860–1940

Farming in the South before the American Civil War focused on large plantations. These plantations grew cotton for export, as well as tobacco and sugar. During the Civil War, the Union Blockade stopped 95 percent of the export business. Some cotton was smuggled out, and northern buyers bought cotton in areas taken by the Union army. Most white farmers worked on small farms, growing food for their families and local markets.

After the war, the price of cotton dropped. Plantations were divided into smaller farms for freed people. Poor white farmers also started growing cotton because they needed money for taxes.

Sharecropping became common in the South after slavery ended. It was a way for very poor farmers, both Black and white, to make a living from land they didn't own. The landowner provided land, a house, tools, seeds, and sometimes a mule. A local merchant provided food and supplies on credit. At harvest time, the sharecropper received a share of the crop (usually one-third to one-half). They used their share to pay back the merchant. This system started with Black farmers on divided plantations. By the 1880s, white farmers also became sharecroppers. This was different from a tenant farmer, who rented land, provided their own tools, and got half the crop. Landowners watched sharecroppers more closely than tenant farmers. Poverty was common because world cotton prices were low.

From the 1860s to the 1920s, southern farmers preferred mules over horses for farm work. Mules handled the summer heat better. Their smaller size and hooves were good for crops like cotton, tobacco, and sugar. It was hard to create pastures in the lower South, so mule breeding happened mostly in states like Missouri, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Mules were a good choice for Southern farming until tractors became common. By the mid-1900s, Texas began to change from a farming state to one with more cities and factories.

The Grange: Helping Farmers Unite

The Grange was an organization started in 1867 for farmers and their wives. It was strongest in the Northeast. The Grange helped farmers modernize their practices and improve family and community life. It still exists today.

Membership grew quickly from 200,000 in 1873 to over 858,000 in 1875. Many local Grange groups took political action, especially about the cost of railroad transportation. The organization was special because it allowed women and teenagers to be equal members. With more members, the national organization had more money from dues. Many local Granges started consumer cooperatives, which were like shared stores.

However, poor money management and fast growth caused membership to drop. By the early 1900s, the Grange recovered and membership became stable. In the mid-1870s, state Granges in the Midwest helped pass laws that controlled the rates railroads and grain warehouses could charge. The Grange also played a big role in creating the federal government's Cooperative Extension Service, Rural Free Delivery (mail service to rural areas), and the Farm Credit System. Their political power peaked when the Supreme Court ruled in Munn v. Illinois that grain warehouses could be regulated by law. During the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s), political parties started supporting Grange ideas. Local Granges then focused more on community service, though the State and National Granges still have political influence.

World War I and Farming

During World War I, the U.S. became a very important supplier to other Allied nations. Millions of European farmers were fighting in the war, so they couldn't grow as much food. Farms in the U.S. grew quickly. New trucks, Model T cars, and tractors helped the farming market expand to a huge size.

Farm prices went up during World War I. Farmers borrowed a lot of money to buy more land and expand their farms. This left them with high debts. When farm prices dropped in 1920, they were in trouble. Throughout the 1920s and until 1934, low prices and high debt were big problems for farmers everywhere.

Starting in 1917, the government encouraged "Victory gardens." These were gardens planted in private yards and public parks for personal use and to help the war effort. These gardens produced over $1.2 billion worth of food by the end of World War I. Victory gardens were also encouraged during World War II when food was rationed.

The 1920s: Changes on the Farm

A popular song from 1919 asked, "How Ya Gonna Keep 'em Down on the Farm (After They've Seen Paree)?" This song hinted that many young people returning from World War I did not stay on the farm. Many moved to nearby towns and smaller cities. The average distance they moved was only about 10 miles. Few went to very large cities.

However, farming became more mechanized. Tractors and other heavy equipment became common. Better farming techniques were shared through County Agents. These agents worked for state agricultural colleges and were funded by the federal government.

The early 1920s saw a fast growth in American agriculture. This was mainly due to new technologies and machines. Competition from Europe and Russia had disappeared because of the war. American farm goods were shipped all over the world.

New machines like the combine harvester meant that larger farms were more efficient. Slowly, the small family farm model began to change. Larger, more business-focused farms became more common. Even with these changes, most farm production was still done by family-owned businesses.

World War I had created high prices for farm products because European countries needed more food. Farmers had a good time as U.S. farm production grew fast to fill the gap. When the war ended, Europe's farms recovered, and supply increased quickly. Too much production led to falling prices. This caused tough times and lower living standards for farmers in the 1920s. Worse, many farmers had taken out loans to buy more land during the good times. Now, they couldn't pay their debts. Farmers blamed the fall in foreign markets and protective tariffs for their problems.

Farmers asked for help as the farming depression got worse in the mid-1920s, while the rest of the economy was doing well. Farmers had a strong voice in Congress. They asked for government money, especially through the McNary–Haugen Farm Relief Bill. This bill passed but was stopped by President Calvin Coolidge. Coolidge supported a different plan from Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover and Agriculture Secretary William M. Jardine. Their plan was to modernize farming by bringing more electricity, better equipment, better seeds and animals, more rural education, and better business practices. Hoover wanted a Federal Farm Board to limit crop production to what the country needed. He believed farmers' problems were due to poor distribution. In 1929, Hoover's plan was adopted.

The 1930s: The Great Depression and New Deal

President Franklin D. Roosevelt cared a lot about farming. He believed that the country wouldn't truly recover until farming was doing well. Many different New Deal programs were created to help farmers. Farming hit its lowest point in 1932. Even then, millions of unemployed people moved back to family farms after losing hope for jobs in cities. The main New Deal idea was to reduce the amount of crops produced. This would raise prices a little for consumers and a lot for farmers. Small farmers who didn't produce much weren't helped by this. Special programs were made for them. By 1936, farming was largely doing well again.

Roosevelt's "First Hundred Days" led to the Farm Security Act. This act aimed to raise farm incomes by increasing the prices farmers received. It did this by reducing the total amount of farm products. In May 1933, the Agricultural Adjustment Act created the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). This act reflected what major farm groups wanted.

The AAA's goal was to raise prices for farm products by creating a shortage. The AAA set limits on how much corn, cotton, dairy products, hogs, rice, tobacco, and wheat could be produced. Farmers themselves had a say in how the government helped their incomes. The AAA paid landowners to leave some of their land unplanted. This money came from a new tax on food processing. The goal was to push farm prices up to a "parity" level, which was based on prices from 1910–1914. To meet the 1933 goals, 10 million acres of cotton were plowed under. Good crops were left to rot, and six million piglets were killed. The idea was that less production would mean higher wholesale prices and more income for farmers. Farm incomes grew a lot in the first three years of the New Deal as prices for goods rose. Food prices remained much lower than 1929 levels.

The AAA created a long-lasting role for the federal government in planning the entire farming part of the economy. It was the first program of its kind to help the struggling farming economy. The original AAA didn't help sharecroppers, tenants, or farm laborers who lost jobs. But other New Deal programs, like the Farm Security Administration, were created for them.

In 1936, the Supreme Court of the United States said the AAA was unconstitutional for technical reasons. It was replaced by a similar program that the Court approved. Instead of paying farmers to leave fields empty, the new program paid them to plant soil-enriching crops like alfalfa that wouldn't be sold. Federal rules for farm production have changed many times since then. But the basic idea of giving money to farmers is still in place today.

Helping Rural Areas

Many rural people lived in deep poverty, especially in the South. Major programs helped them. These included the Resettlement Administration (RA) and the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). Other projects helped rural areas too, like school lunches, building new schools, opening roads in remote areas, planting trees, and buying poor quality land to expand national forests. In 1933, the government started the Tennessee Valley Authority. This project built many dams to stop floods, create electricity, and modernize poor farms in the Tennessee Valley region.

For the first time, there was a national plan to help migrant and poor farmers. This was done through programs like the Resettlement Administration and the Farm Security Administration. Their difficult lives gained national attention through the 1939 novel and film The Grapes of Wrath. The New Deal believed there were too many farmers. It didn't give loans to the poor to buy farms. However, it made a big effort to improve health care for people who were often sick.

Farming During World War II

Farming did well during World War II. Even though rationing and price controls limited meat and other foods for regular people, it made sure there was enough for American and Allied soldiers. During World War II, farmers were not drafted into the army. But many extra farm workers, especially in the southern cotton fields, moved to cities to work in war factories.

During World War II, victory gardens planted at homes and public parks were an important source of fresh food. The United States Department of Agriculture encouraged these gardens. About one-third of the vegetables grown in the United States came from victory gardens.

Farming from 1945 to Today

Government Policies

Farm programs from the New Deal era continued into the 1940s and 1950s. Their goal was to support the prices farmers received for their products. Typical programs included farm loans, payments for certain crops, and price supports. As the number of farmers dropped, they had less influence in Congress. So, groups like the Farm Bureau worked in the 1970s to get support from city lawmakers by linking farm bills to food stamp programs for the poor. By 2000, the food stamp program was the largest part of the farm bill. In 2010, the Tea Party movement wanted to cut all federal payments, including those for farming. However, city Democrats strongly opposed cuts, pointing to the hard times caused by the 2008–10 economic problems. Even though many rural Republican lawmakers voted against the farm program in 2014, it passed with support from both major parties.

New Technology in Farming

After World War II, factories that made explosives started producing ammonia for fertilizers. This led to lower fertilizer prices and more use of them. The early 1950s was when the most tractors were sold in the U.S. The last mules and work horses were sold. Farm machines also became much more powerful. A successful cotton picking machine was introduced in 1949. This machine could do the work of 50 people picking cotton by hand. Most unskilled farm workers moved to cities.

Research in plant breeding created new types of grain crops that could produce a lot more food with heavy fertilizer use. This led to the Green Revolution, starting in the 1940s. By 2000, corn (maize) yields had increased more than four times. Wheat and soybean yields also grew a lot.

Farming Economy and Workers

After 1945, farm productivity continued to increase by about 2% each year. This led to even larger farms and fewer farms overall. Many farmers sold their land and moved to nearby towns and cities. Others started farming part-time and worked other jobs to make money.

The 1960s and 1970s saw major farm worker strikes. These included the 1965 Delano grape strike and the 1970 Salad Bowl strike. In 1975, California passed a law giving farmworkers the right to collective bargaining, which was a first in U.S. history. Important leaders in farm worker organizing during this time included Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta, Larry Itliong, and Philip Vera Cruz. Chavez helped organize California workers into the United Farm Workers group.

In 1990, about 14 percent of farm workers were undocumented. By 2000, this number grew to over 50% and has stayed around that level. In 2015, grain farmers started breaking their land lease contracts. They reduced the amount of land they planted, risking legal fights with landowners. This was a big step not widely seen since the 1980s.

Farming Innovations

New machines, especially large self-propelled combines and mechanical cotton pickers, greatly reduced the need for human labor in harvesting. Electric motors and irrigation pumps also made farming more efficient. Electricity helped with major improvements in animal husbandry, like modern milking parlors, grain elevators, and large animal feeding operations (CAFOs).

There were also big advances in fertilizers, herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides. The use of antibiotics and growth hormones in animals also improved. Significant progress was made in plant breeding and animal breeding, such as creating hybrid crops, GMOs (genetically modified organisms), and artificial insemination of livestock. After harvesting, there were innovations in food processing and food distribution, like frozen foods.

Important Crops in U.S. History

Wheat: A Key Grain

Wheat, used for bread, pastries, pasta, and pizza, has been the main cereal crop since the 1700s. The first English colonists brought it, and it quickly became a main crop for farmers to sell to cities and for export. In colonial times, it was mostly grown in the Middle Colonies, which were called the "bread colonies." In the mid-1700s, wheat farming spread to Maryland and Virginia. George Washington was a well-known wheat grower as he moved away from tobacco.

The crop moved west, with Ohio as a main center in 1840 and Illinois in 1860. Illinois later grew more corn to feed hogs. New machines for harvesting, first pulled by horses and then by tractors, made larger farms much more efficient. Farmers had to borrow money to buy land and equipment. They specialized in wheat, which made them sensitive to price changes and led them to ask for government help. Wheat farming needed a lot of workers only during planting and especially at harvest time. So, successful farmers, especially on the Great Plains, bought as much land as possible. They bought expensive machines and relied on migrant workers during harvest. These migrant families often lived in poverty, except during harvest season. Since 1909, North Dakota and Kansas have been the top wheat producers, followed by Oklahoma and Montana.

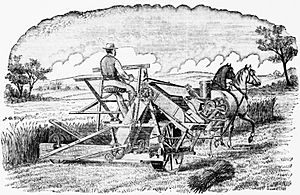

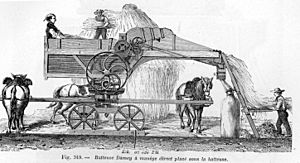

In the colonial era, wheat seeds were scattered by hand. It was cut with sickles and threshed (separated from the stalk) with flails. The kernels were then taken to a mill to be ground into flour. In 1830, it took four people and two oxen, working 10 hours a day, to produce 200 bushels of wheat. New technology greatly increased production in the 1800s. Drills replaced hand scattering for planting. Cradles replaced sickles for cutting. Then, reapers and binders replaced cradles. Steam-powered threshing machines took the place of flails. By 1895, on large farms in the Dakotas, six people and 36 horses pulling huge harvesters could produce 20,000 bushels in 10 hours. In the 1930s, the gasoline-powered "combine" machine did both cutting and threshing in one step, operated by just one person. Wheat production grew from 85 million bushels in 1839 to 1 billion bushels in 1915. Prices changed a lot, with a drop in the 1890s that caused problems in the Plains states.

How wheat was sold also changed. Transportation costs fell, and more distant markets opened up. Before 1850, wheat was put in sacks, shipped by wagon or canal boat, and stored in warehouses. With the growth of railroads in the 1850s–1870s, farmers took their harvest by wagon to the nearest country elevators. The wheat then moved to larger elevators, where it was sold through grain exchanges to flour mills and exporters. Since elevators and railroads often had a local monopoly, farmers sometimes complained about unfair grading, short weighing, and too many fees. Scandinavian immigrants in the Midwest took control of marketing by forming cooperatives.

New Types of Wheat

After the steel roller mill was invented in 1878, hard types of wheat like Turkey Red became more popular. Before, soft wheat was preferred because it was easier to grind. Wheat production saw big changes in types of wheat and farming methods after 1870. Thanks to these new ideas, large areas of the wheat belt now produce wheat for sale. Yields have also resisted damage from insects, diseases, and weeds. New biological ideas helped increase labor productivity by about half between 1839 and 1909.

In the late 1800s, tough new wheat types from Russia were brought to the Great Plains by Volga Germans who settled in North Dakota, Kansas, Montana, and nearby states. Many people believe that the miller Bernhard Warkentin (1847–1908), a German Mennonite from Russia, brought the "Turkey red" variety. More accurately, in the 1880s, many millers and government agricultural agents worked to create "Turkey red" and make Kansas the "Wheat State." The U.S. Department of Agriculture and state experiment stations have developed many new varieties and taught farmers how to plant them. Similar types of wheat now dominate in the dry regions of the Great Plains.

Selling Wheat to Other Countries

Wheat farmers have always produced more wheat than the U.S. needed, so they could sell it to other countries. Exports were small until the 1860s. Then, bad harvests in Europe and lower prices due to cheaper railroad and ocean transport opened up European markets. The British, in particular, relied on American wheat for a quarter of their food supply in the 1860s. By 1880, 150 million bushels were exported, worth $190 million.

During World War I, many young European farmers were forced to join the army. So, Allied countries like France and Italy depended on American wheat shipments, which ranged from 100 million to 260 million bushels a year. American farmers responded to the high demand and prices by growing more wheat. Many took out loans to buy their neighbors' farms. This led to a large surplus in the 1920s. The resulting low prices made growers ask for government help to support prices. This led to the McNary-Haugen bills, which didn't pass, and later the New Deal's Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933.

World War II brought a huge increase in production, reaching a billion bushels in 1944. During and after the war, large amounts of wheat and flour were exported as part of Lend-Lease and foreign aid programs. In 1966, exports reached 860 million bushels, with 570 million given away as food aid. A major drought in the Soviet Union in 1972 led to the sale of 390 million bushels. An agreement was signed in 1975 to supply the Soviets with grain for five years.

How Wheat is Marketed

By 1900, private grain exchanges set the daily prices for North American wheat. After 1933, the AAA programs set wheat prices in the U.S. Canada created a wheat board to do the same there. The Canadian government required farmers to deliver all their grain to the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB), a single agency that took over private wheat marketing in western Canada. Meanwhile, the United States government helped farm incomes with taxes on domestic use and import tariffs, but it kept private wheat marketing.

Cotton: A Major Southern Crop

In the colonial era, small amounts of high-quality long-staple cotton were grown on the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina. Inland, only short-staple cotton could be grown. But it had many seeds and was very hard to turn into fiber. The invention of the cotton gin in the late 1790s made short-staple cotton useful for the first time. It was usually grown on plantations from South Carolina westward, with the work done by enslaved people.

At the same time, the fast growth of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, focused on making textiles, created a huge demand for cotton fiber. Cotton quickly used up the soil's nutrients. So, planters used their large profits to buy new land to the west and buy more enslaved people from the border states to work their new plantations. After 1810, the new textile mills in New England also created a big demand. By 1820, over 250,000 bales (each weighing 500 pounds) were sent to Europe, worth $22 million. By 1840, exports reached 1.5 million bales worth $64 million, making up two-thirds of all American exports. Cotton prices kept going up as the South remained the main supplier in the world. In 1860, the U.S. shipped 3.5 million bales worth $192 million.

After the American Civil War, cotton production spread to small farms. These farms were worked by white and Black tenant farmers and sharecroppers. The amount exported stayed steady at 3 million bales, but world market prices fell. While planting seeds and removing weeds took some work, the most important labor for cotton was picking it. How much cotton a farm could produce depended on how many people (men, women, and children) were available. Finally, in the 1950s, new mechanical harvesters allowed a few workers to pick as much cotton as 100 people had done before. This led to many white and Black cotton farmers leaving the South. By the 1970s, most cotton was grown on large, automated farms in the Southwest.