Delano grape strike facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Delano grape strike |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

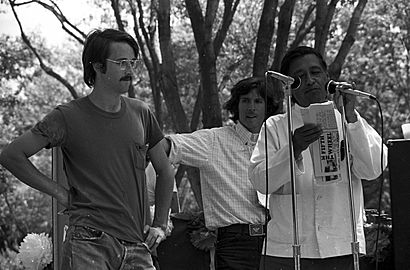

Chavez speaking at a 1974 United Farm Workers rally in Delano, California.

|

|||

| Date | September 7, 1965 - July 1970 | ||

| Location |

Delano, California

|

||

| Goals | Minimum wage | ||

| Methods | Strikes, boycotting, Demonstrations | ||

| Resulted in | Collective bargaining agreement | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|

|||

| Number | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

|

|||

The Delano grape strike was a big protest by farm workers in Delano, California. It started in 1965 and lasted for five years. Workers wanted better pay and fairer treatment from grape growers.

The strike was led by two main groups: the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), mostly Filipino workers, and the National Farmworkers Association (NFWA), mostly Mexican workers. These groups later joined together to form the United Farm Workers (UFW).

The workers used peaceful methods like boycotts (asking people not to buy grapes), marches, and community organizing. These actions helped them get national attention. In July 1970, the strike ended with a win for the workers. They signed an agreement with grape growers, which improved conditions for over 10,000 farm workers.

The Delano grape strike is famous for showing how powerful boycotts can be. It also showed how Filipino and Mexican farm workers could work together. This unity led to the creation of the UFW, which changed the farm labor movement in America.

Contents

Why the Strike Started

Before the Delano strike, Filipino farm workers had another strike in Coachella Valley, California, in May 1965. Many of these workers were older and didn't have families. This meant they were willing to take risks to fight for better wages.

That strike helped them get a raise to $1.40 per hour. This was the same wage that workers in the Bracero program used to get. After the Coachella strike, these Filipino workers moved north to Delano to pick grapes there.

When they arrived in Delano, growers told them they would only be paid $1.20 per hour. This was less than the federal minimum wage. Larry Itliong, a leader of the AWOC, tried to talk to the growers. But the growers refused to raise wages because they could easily find new workers.

So, on September 7, 1965, Itliong and the Filipino farm workers met. They all voted to go on strike the very next morning.

Key Events of the Strike

Workers Unite for Justice

On September 8, 1965, over 1,000 Filipino farm workers, led by Itliong and others, stopped working. They began their strike against the grape growers in Delano. In response, growers hired Mexican farm workers to cross the picket lines. This was a common tactic to cause conflict between the two groups.

To keep the strike strong, Itliong asked Cesar Chavez, leader of the NFWA, for help. Chavez was unsure at first because his group didn't have much money. But NFWA members really wanted to support the Filipinos.

So, Chavez held a meeting on September 16, 1965. More than 1,200 supporters came. They voted strongly to join the strike, chanting "Huelga!" which means "Strike!" in Spanish. This day marked the official joining of Filipino and Mexican farm workers. They began picketing together to fight for fair treatment.

The March to Sacramento

On March 17, 1966, Cesar Chavez began a 300-mile march. He walked from Delano to Sacramento, the state capital. This march aimed to pressure growers and the government to meet the workers' demands. It also brought a lot of public attention to the farm workers' cause.

Soon after this march, the NFWA and the AWOC officially merged. They became the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee. In August 1966, this new group became the official United Farm Workers (UFW) union.

Peaceful Protests and Boycotts

After a big grape harvest in late 1965, thousands of California farm workers went on strike. They demanded the right to have union elections. Many workers were arrested by police or hurt by growers while picketing. Growers used many ways to scare and bother the picketers.

The growers knew the strikers were committed to nonviolence. So, they would push, punch, or jab elbows into the strikers. Some growers even drove their cars towards protesters, swerving away at the last moment. In some cases, pesticide spraying equipment was used to spray picketers. This temporarily blinded them.

Chavez kept telling the workers not to react with violence. He wanted them to react in ways that would help them reach their goal. He believed they could change the world through nonviolent action.

Chavez sent workers to follow a grape shipment to the Oakland docks. There, they convinced the longshoremen (dock workers) not to load the grapes. This worked, and thousands of cases of grapes were left to rot. This success led to the decision to use boycotting as a main tactic.

This first successful boycott led to more protests at Bay Area docks. The International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union helped the protesters. They refused to load grapes from non-union farms.

Chavez's success with boycotts inspired him to start formal boycotts. He targeted two of the biggest grape companies: Schenley Industries and the DiGiorgio Corporation.

Victories and Contracts

Starting in December 1965, Chavez's group began boycotting the Schenley corporation. The pressure from supporters in businesses helped the farm workers win. They got union contracts that immediately raised wages. They also set up hiring halls in Delano and other areas.

Some large companies tried to scare workers to protect their profits. For example, one company hired criminals to break up union voting. They attacked voters, flipped tables, and smashed ballot boxes.

The DiGiorgio Corporation was finally forced to hold an election for its workers on August 30, 1967. This happened because the boycott stopped their grapes from reaching stores. Workers voted 530 to 332 in favor of the UFW. The Teamsters union was the only other union in the election.

In 1970, the grape strike and boycott finally ended. Grape growers signed labor contracts with the UFW. These contracts included regular pay raises, health benefits, and other good conditions for workers.

Where the Strike Spread

The grape strike began in Delano in September 1965. By December, union representatives traveled across the country. They went to cities like New York, Washington, D.C., and Detroit. They encouraged people to boycott grapes from farms without UFW contracts.

In 1966, unions and religious groups in Seattle and Portland supported the boycott. Canadians also showed strong support.

In 1967, UFW supporters in Oregon started picketing stores. After melon workers went on strike in Texas, the UFW became the first union to sign a contract with a grower there.

National support for the UFW grew even more in 1968. Hundreds of UFW members and supporters were arrested. Protests continued across the country. Mayors of major cities like New York and Detroit pledged their support. Many cities changed their grape purchases to help the boycott.

In 1969, support for farm workers grew throughout North America. The grape boycott spread to the South. Civil rights groups pushed grocery stores to remove non-union grapes. Student groups protested the Department of Defense for buying boycotted grapes. On May 10, UFW supporters picketed Safeway stores across the U.S. and Canada. Cesar Chavez also traveled to ask for support from different groups.

This map shows over 1,000 farm worker strikes and boycotts from 1965-1975.

Challenges Within the Union

Organizing the grape strike took a lot of planning and effort. There were some disagreements between the different groups and people involved.

At first, it was mainly Larry Itliong's Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), made up mostly of Filipinos. Itliong realized he needed a bigger union to make a real difference. He reached out to Cesar Chavez, who led the Mexican National Farm Workers Association (NFWA). They decided to merge their groups to form the United Farm Workers (UFW).

Before the merger, both groups worried about being taken over by the other. Itliong and Chavez also had some doubts about working together. But they knew joining forces was necessary to succeed. Despite their differences, the farmers worked together. They won better pay, a bonus for each grape box, and improved working conditions.

Later, after the strike, Itliong decided to leave the UFW. This was due to disagreements and different ideas about how the union should be run.

Impact of the Strike

The Delano strike and related events from 1960 to 1975 were a big victory for the UFW and farm workers. By 1968, the UFW had signed contracts with 10 different grape growers, including Schenley Industries and DiGiorgio Corporation. But the strikes and boycotts continued until 1970. That's when 26 grape growers signed contracts with the UFW.

These contracts were the first of their kind in farming history. They immediately led to higher wages and better working conditions. Some contracts also included unemployment insurance, paid vacation days, and a special benefits fund.

After the grape strike ended in 1970, a new strike began against lettuce growers. This led to some conflict with the Teamsters union in the Salinas Valley.

In June 1975, California passed a law allowing farm workers to vote secretly for union representation. By mid-September, the UFW won the right to represent 4,500 workers at 24 farms. The Teamsters won the right to represent 4,000 workers at 14 farms. The UFW won most of the elections they were in.

In 1977, the Teamsters signed an agreement with the UFW. They promised to stop trying to represent farm workers. The boycotts of grapes, lettuce, and Gallo Winery products officially ended in 1978.

Even with these successes, there were some tough outcomes for farm workers. One major issue was that the relationship between Filipino and Mexican farm workers became strained. The UFW created a "hiring hall" system in the first contracts. This system was meant to stop workers from having to migrate all the time. But it ended up splitting up many Filipino workers who were used to moving with the harvest seasons.

After the strike, Cesar Chavez's actions were often highlighted and remembered. The 2014 film Cesar Chavez shows his important role. However, many others who supported him were less remembered. The efforts of Filipino Americans in the strike were often forgotten. For example, in the 2014 film, the Filipino role was mostly missing, except for one speaking line and a few group shots.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Huelga de la uva en Delano para niños

In Spanish: Huelga de la uva en Delano para niños