Monks Mound facts for kids

Monks Mound in summer. The concrete staircase follows the approximate course of the ancient wooden stairs

|

|

| Location | Collinsville, Illinois, Madison County, Illinois, United States |

|---|---|

| Region | Madison County, Illinois |

| Coordinates | 38°39′38.4″N 90°3′43.36″W / 38.660667°N 90.0620444°W |

| History | |

| Founded | 900–950 CE |

| Cultures | Mississippian culture |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | Thomas I. Ramey |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural styles | Platform mound |

| Responsible body: Illinois Historic Preservation Agency | |

Monks Mound is the biggest ancient man-made hill in North and South America. It is also the largest pyramid north of Mesoamerica, a historical region in Central America. People started building it around 900 to 950 CE.

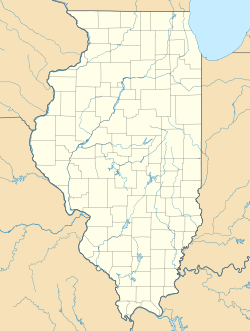

You can find Monks Mound at the Cahokia Mounds UNESCO World Heritage Site. This site is near Collinsville, Illinois. The mound is about 100 feet (30 meters) tall. That's like a 10-story building! It is also about 955 feet (291 meters) long and 775 feet (236 meters) wide.

Its base is roughly the same size as the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt. It is even bigger around its base than the Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacan, Mexico. Monks Mound is a platform mound, which means it had a large wooden building on its flat top.

Unlike Egyptian pyramids made of stone, Monks Mound was built almost entirely from layers of soil and clay. People carried these materials in baskets. Because of this, rainwater can get trapped inside the mound. This has caused parts of the sides to slide down, like a small avalanche. This sliding, called slumping, happened even while the mound was being built.

Contents

Building Monks Mound

The Mississippian culture began building Monks Mound around 900 to 950 CE. The area was already used for other buildings before the mound started. The first idea was to build a much smaller mound. This smaller mound is now buried deep inside the northern part of the huge structure we see today.

Around 1100 CE, the mound was mostly finished. On the northern end of the flat top, there was a slightly raised area. A very large building, over 100 feet (30 meters) long, stood there. This was the biggest building in the entire Cahokia Mounds area.

Scientists think Monks Mound was built faster than previously believed. It might have been finished in just a few decades. Digs in 2007 showed that different types of earth and clay were used. These materials came from various places. Builders also used strong walls of clay and sod (grass with soil) to make the mound more stable. This allowed them to build steeper slopes.

The mound has four levels, like giant steps, and reaches 100 feet (30 meters) high. Its base covers almost 15 acres (6 hectares). It contains 22 million cubic feet of earth. All of this earth was carried basket by basket to the site.

The lowest terrace on the south end was the last part added, before 1200 CE. This might have been to help stop the slumping that was already happening. Today, the western side of the top is much lower than the eastern side. This is because of a huge slump that started around 1200 CE. This event also caused the large building on top to collapse.

After this, the mound might have lost its important status. Other wooden buildings were put on the south terrace, and people even dumped garbage at the mound's base. By about 1300 CE, the society at Cahokia Mounds was in serious decline. When the eastern side of the mound started to slump badly, no one repaired it.

European Settlers Arrive

For hundreds of years after 1400 CE, there is no sign of many Native Americans living at Cahokia Mounds. In 1735, French missionaries built a small church on the west end of the mound's south terrace. This church served a small Illiniwek community. However, rival tribes forced them to leave the area around 1752.

In 1776, during the American Revolutionary War, a trading post called the Cantine was set up near the mound. By then, people called the mound the Great Nobb. This trading post only lasted until 1784.

In the early 1800s, French families owned the land. Nicholas Jarrot gave some land to a group of French Trappist monks. They settled on one of the smaller mounds in 1809. The monks used the big mound's terraces to grow food. They grew wheat on the upper levels and garden vegetables on the south terrace. This kept their crops safe from floods.

During their short stay, a man named Henry Brackenridge visited the site. He wrote the first detailed description of the largest mound. He was the one who named it Monks Mound. In 1831, T. Amos Hill bought the land with the mound. He built a house on the upper terrace and dug a well. These activities uncovered old things, including human bones.

Exploring the Mound: Archaeology

Thomas I. Ramey bought the site in 1864. He cared for the mound and encouraged people to study it. Many old objects were found near the surface. Ramey even had a tunnel dug almost 30 meters (100 feet) into the north side of the mound. But this tunnel did not find anything historically important.

By this time, people started to see the mound as part of a larger area. A survey done for Dr. John R. Patrick in the 1880s helped people understand the entire Cahokia site. It showed how Monks Mound related to other ancient sites nearby.

Many archaeological studies have happened at the mound since then. A big one started in the 1960s. Nelson Reed, a local businessman, got permission to dig. He wanted to find the important building (like a temple or palace) that was thought to be on top of Monks Mound. His team drilled holes into the mound. This showed the different stages of its construction from the 10th to 12th centuries CE. They found parts of a recent house (probably Hill's), but no temple.

In 1970, Reed tried a new method. He used a backhoe to scrape away the topsoil from several small areas. This quickly showed different features, including what looked like the outline of the temple. More backhoe work in 1971 confirmed the shape of the presumed temple. It was over 30 meters (100 feet) long, the largest building found at Cahokia.

Some professional archaeologists did not like this method. They felt it destroyed important layers of soil that showed the mound's history. However, Reed's digs found other important things. For example, they found a hole that seemed to be for a large post, about one meter (three feet) wide. These exciting discoveries encouraged the Governor of Illinois to expand the Cahokia Mounds State Park.

Protecting Monks Mound

After the ancient society collapsed, trees grew all over the great mound. Their roots helped keep its steep sides stable. In the 20th century, researchers removed these trees to work on the mound and prepare the park.

In the 1950s, the water levels in the nearby Mississippi floodplain dropped. This caused the mound to dry out, damaging its clay layers. When heavy rain came, new slumping started around 1956. More extreme weather in recent years has made the problem worse.

In 1984-85, several slumps occurred. The state government brought in extra soil to fix a large scar on the eastern side. Ten years later, more slumping happened on the western side. This time, it was too uneven to repair easily. Drains were put in to reduce the effects of heavy rain. During this work, builders found a large mass of stone deep inside the mound.

The repairs in the 1980s and 1990s were only partly successful. In 2004-05, even more serious slumping happened. This showed that adding new earth to fix the east side had been a mistake. Experts decided to try a new approach.

In 2007, backhoes were used to dig out all the earth from the slump on the east side and another at the northwest corner. They dug past the sliding zone. Engineers then created anti-slip "steps" on the exposed surface. After that, the original earth (without the added repair material) was put back. To avoid adding water deep inside the mound, the work was done quickly in the summer.

While the repairs were happening, archaeologists studied what was uncovered. The eastern sliding zone went deeper into the mound than first thought. The excavation had to be very large: 50 feet (16 meters) wide and 65 feet (20 meters) high above the mound's base. This raised concerns about balancing conservation with archaeological study.

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |