Interior Plains facts for kids

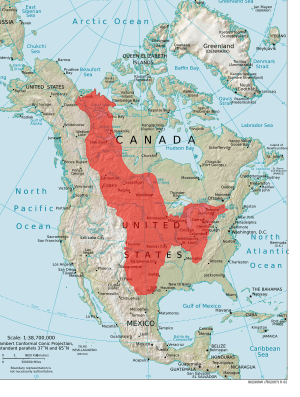

The Interior Plains are a huge, mostly flat or gently rolling area in the middle of North America. They stretch from the warm Gulf of Mexico all the way up to the cold Arctic in Canada. Imagine a giant, mostly flat carpet covering a huge part of the continent! This region is found east of the towering Rocky Mountains and west of the ancient Appalachian Mountains and the rocky Canadian Shield.

In Canada, the Interior Plains include the Canadian Prairies, known for their wide-open spaces and farms. They also cover the Boreal Plains and Taiga Plains, which have many forests. In the United States, this region includes the Great Plains in the West and Midwest, and the tallgrass prairies near the Great Lakes.

Contents

How the Interior Plains Were Formed

The story of the Interior Plains began billions of years ago. Huge pieces of Earth's crust, called tectonic plates, slowly moved and crashed into each other. These powerful collisions created mountains and caused the land to change. Over millions of years, these mountains eroded, and their pieces (sediments) were carried by water and wind to form the layers of rock we see today in the plains.

Ancient Earth: The Proterozoic Eon

About 2 billion to 1.8 billion years ago, several ancient landmasses (called cratons) joined together. This big event, known as the Trans-Hudson Orogeny, helped create the core of North America. Mountains formed along the edges of these joining landmasses.

While mountains rose on the edges, the center of this new continent stayed mostly flat. It became like a giant bowl, collecting sediments from the eroding mountains. One of the few places where these ancient rocks can still be seen at the surface today is in the Black Hills of South Dakota. These rocks are very old and have been changed a lot by heat and pressure.

Life Explodes: The Paleozoic Era

This era, from about 539 to 252 million years ago, was a time of amazing change. The oceans became full of complex life during an event called the Cambrian explosion. As continents moved, the Appalachian Mountains began to form about 400 million years ago. Later, all the continents came together to form a supercontinent called Pangea.

During this time, the central plains of North America were covered by sediments washed down from the growing mountains. These sediments included layers of sandstone, shale, limestone, and even coal. Today, these ancient layers are buried deep underground.

Dinosaurs and Inland Seas: The Mesozoic Era

Around 220 million years ago, Pangea started to break apart. North America began to drift westward. For much of this era, the Interior Plains were covered by vast inland seas.

During the Jurassic period, the Sundance Sea stretched from Canada down into parts of the United States, like Wyoming and Montana. It left behind layers of sandstone and other marine rocks. Later, in the Cretaceous period, an even bigger sea formed: the Western Interior Seaway. This huge body of water covered almost all the Interior Plains west of the Mississippi River, from Alaska to the Gulf of Mexico. It left behind layers of limestone and shale.

Towards the end of this era, the land began to rise as the Rocky Mountains started to form. This caused the inland seas to slowly drain away.

Modern Landscape: The Cenozoic Era

The Cenozoic Era, from 66 million years ago to today, saw the final shaping of the Rocky Mountains. This mountain-building event, called the Laramide Orogeny, created the tall peaks we see today. The rocks in the Rockies include sandstone, granite, and limestone; some of which were pushed up from very deep underground.

The Interior Plains have remained mostly flat during this time. Sediments continue to be carried by rivers and wind from the Rocky Mountains to the west and the Appalachians to the east, constantly adding to the plains.

Ice Age and Lakes: Glacial History

About 2.6 million years ago, during the Pleistocene Epoch (also known as the Ice Age), a massive ice sheet called the Laurentide Ice Sheet began to spread across North America. It covered much of Canada and parts of the northern United States, including the northern Great Plains.

As this giant ice sheet moved, it scraped and carved the land. When the climate warmed and the ice melted, it left behind many features. The ice created deep hollows that filled with water, forming thousands of lakes. The Great Lakes (like Lake Superior and Lake Michigan) and Canada's Great Slave Lake and Great Bear Lake were all formed by this powerful ice sheet.

For example, the state of Minnesota is famous for its many lakes, often called "the Land of 10,000 Lakes." These were mostly formed by the retreating glaciers.

The glaciers also helped create a special type of soil called loess. As the ice melted, it released sand and silt into rivers. Strong winds then picked up this fine material and spread it across the Interior Plains, creating fertile soil.

How Sediment Moves Across the Plains

Sediment (like sand, silt, and clay) is constantly moving across the Interior Plains. The main ways it moves are by wind (called aeolian processes) and by water (called fluvial processes).

Rivers and Dams: Fluvial Processes

Rivers are natural transporters of sediment. They carry soil and rock particles from higher elevations to lower ones. However, human projects like dams and other structures built on rivers can change this natural process.

For example, the Mississippi River used to carry about 400 million tons of sediment to the Gulf of Mexico each year before 1900. But after many dams and other engineering projects were built on rivers like the Missouri River (a major tributary of the Mississippi), the amount of sediment reaching the Gulf has dropped significantly. These structures trap the sediment, changing how rivers shape the land.

Wind and Dust: Aeolian Processes

The Interior Plains, especially the southern parts, can experience droughts because they don't always get a lot of rain. When the weather is warm and dry, the soil can become loose and easily picked up by the wind. This is called soil erosion.

A good example of wind erosion is the widespread loess deposits found across the plains. These fine, wind-blown dust layers were laid down during the Ice Age. The Nebraska Sand Hills are another example, formed by strong winds depositing sand and silt.

After World War I, many prairies in the Interior Plains were turned into wheat farms. These prairies had strong grasses that held the soil in place. When the grasses were removed, the soil became much more vulnerable to wind erosion. During a severe drought in the 1930s, this led to the infamous Dust Bowl. Huge dust storms swept across the region, carrying away millions of tons of valuable topsoil.

To help prevent this from happening again, people planted long rows of trees called shelterbelts. These tree lines help slow down the wind and protect the soil from being blown away.

What the Land is Used For Today

The Interior Plains are a very important region for both Canada and the United States.

Most of the land in the U.S. part of the Interior Plains (about 44%) is covered by grasslands and shrublands. These areas are home to different types of grasses. In the west, you'll find short grasses like blue grama. In the east, there are tall grasses like big bluestem. In between, there's a mix of both. These grasslands are vital for raising cattle, supporting nearly 50% of all beef cattle in the United States.

In Canada, the provinces within the Interior Plains also produce a large amount of beef cattle, nearly 60% of the country's total.

A huge portion of the Interior Plains is used for agriculture. In the year 2000, almost 44% of the Great Plains area was farmland. Wheat is the biggest crop grown here, and the Interior Plains produce more than half of the world's wheat exports! Other important crops include barley, corn, cotton, sorghum, soybeans, and canola (especially important in Canadian exports).

Smaller parts of the land are used for forests (about 5.8%), wetlands (1.6%), developed areas (1.5%), barren land (0.6%), and mining (0.1%).

Different Parts of the Interior Plains

The Interior Plains are so large that they are divided into smaller areas based on their physical features. Both Canada and the United States have their own ways of classifying these regions.

Interior Plains in Canada

In Canada, the Interior Plains are one of seven main geographic regions. Within this region, there are 14 smaller areas called "physiographic divisions." You can learn more about them at the Canadian atlas website.

- Alberta Plain

- Alberta Plateau

- Anderson Plain

- Colville Hills

- Cypress Hills

- Fort Nelson Lowland

- Great Bear Plain

- Great Slave Plain

- Horton Plain

- Manitoba Plain

- Peace River Lowland

- Peel Plain

- Peel Plateau

- Saskatchewan Plain

Interior Plains in the United States

In the United States, the Interior Plains are divided into three main "provinces," which are then broken down into even smaller "sections."

Central Lowland

- Dissected Till Plains

- Eastern Lake

- Osage Plains

- Till Plains

- Western Lake

- Wisconsin Driftless

Great Plains

- Black Hills

- Central Texas

- Colorado Piedmont

- Edwards Plateau

- High Plains

- Missouri Plateau, Glaciated

- Missouri Plateau, Unglaciated

- Pecos Valley

- Plains Border

- Raton

Interior Low Plateau

- Highland Rim

- Lexington Rim

- Nashville Basin

Animals of the Interior Plains

The animals of the Interior Plains are as diverse as the landscapes they inhabit.

- American Bison:The iconic symbol of the plains. These massive herds once numbered in the tens of millions and shaped the very ecosystem through their grazing habits. While nearly driven to extinction, they now thrive in protected parks and private ranches.

- Pronghorn: Often called an "antelope," though it's not a true one. It is the fastest land mammal in North America, capable of speeds over 55 mph (88 km/h).

- Coyote: A highly adaptable and intelligent canine predator. They are a keystone species, controlling populations of small mammals and serving as a scavenger.

- Black-tailed Prairie Dog: These highly social rodents live in large underground "towns" that can span hundreds of acres.

- American Badger: A powerful digger that often hunts alongside coyotes.

- White-tailed Jackrabbit: Actually a hare, it relies on incredible speed and long ears to regulate body heat and detect predators in the open terrain.

The plains are a critical biome for many bird species, especially for nesting and during migration.

- Burrowing Owl: These small, long-legged owls don't dig their own homes. Instead, they live in abandoned prairie dog burrows, a classic example of commensalism.

- Sharp-tailed Grouse and Greater Sage-Grouse: Known for their spectacular communal mating rituals called "lekking," where males gather and display to attract females.

- Ferruginous Hawk: The largest North American hawk, it is a powerful predator of the open plains.

- Meadowlarks: They are a classic sight and sound of the grasslands, often perched on fences.

- Upland Sandpiper: A shorebird that adapted to life on dry plains.

- Golden Eagle: A massive bird of prey that nests on cliffs and preys on mammals like jackrabbits and young pronghorn.

As the plains extend north into Canada, the landscape transitions to boreal forest and eventually tundra, hosting a different set of animals.

- Moose

- Elk (Wapiti)

- Black Bear and Grizzly Bear

- Timber Wolf

- Snowshoe Hare

- Caribou

See also

In Spanish: Llanuras Interiores para niños

In Spanish: Llanuras Interiores para niños

- Prairie

- Prairies Ecozone

- Canadian Prairies

- Geography of North America

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |