Ghana Empire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ghana Empire

غانا

Wagadu واغادو |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 300–c. mid-1200s | |||||||||||||||||||

The Ghana Empire at its greatest extent

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Koumbi Saleh (likely a later capital) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Soninke, Malinke, Mande | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | African traditional religion Later Islam |

||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Feudal Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ghana | |||||||||||||||||||

|

• 700

|

Kaya Magan Cissé | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• 790s

|

Dyabe Cisse | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• 1040–1062

|

Ghana Bassi | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | 3rd century–13th century | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

c. 300 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• Conversion to Islam

|

1076 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

• Conquered by Sosso/Submitted to the Mali Empire

|

c. 15th century c. mid-1200s | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||

The Ghana Empire, also called Wagadu, was a powerful ancient kingdom in West Africa. It was located in parts of what are now Mauritania and Mali.

Historians aren't sure exactly when the Ghana Empire began. The first written records mentioning its rulers appeared around the year 830. Much of what we know comes from an 11th-century scholar named al-Bakri, who wrote about the region.

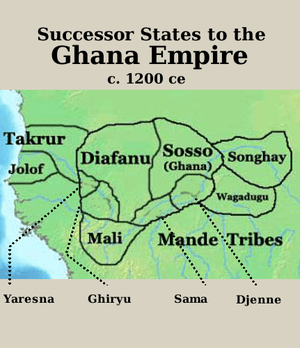

After many years of success, the empire slowly became weaker. By the 13th century, it became a smaller state under the powerful Mali Empire. Even after its decline, the Ghana Empire left a lasting mark, helping to create many towns in the area. In 1957, a modern country, the Gold Coast, chose the name Ghana when it became independent, honoring this ancient empire.

Contents

The Ancient Ghana Empire

What Does "Ghana" Mean?

The word Ghana meant "warrior" or "war chief." It was a special title for the kings of this kingdom. Another title for these kings was Kaya Maghan, which meant "king of gold." The local people, called the Soninke, called their kingdom Ouagadou. This name might have meant "place of the Wague" (a group of important people) or "the land of great herds."

How We Know About Ghana's Origins

Stories from the Past

Local oral traditions tell different stories about how the Ghana Empire began. One popular legend speaks of a man named Dinga, who came from the east. He traveled across West Africa, and his children became the ancestors of important families. To gain power, Dinga had to defeat a serpent spirit named Bida. Some stories say he made a deal with Bida for rain and gold, in exchange for a yearly sacrifice. After Dinga passed away, his sons fought for the throne, and Dyabe won, becoming the founder of Wagadu.

Other stories explain the empire's decline. One tale says that a nobleman broke the deal with the serpent by saving a maiden, which brought a curse upon the land. This legend is still very important in Soninke culture today.

Traditions from other groups in the region, like the Moors and Berbers, also say that the first people in these areas were Black Africans. These regions were central to the Ghana Empire for a long time.

What Old Writers Said

Early writers from the Middle Ages, like those who wrote the Tarikh al-Fattash and Tarikh al-Sudan, also tried to explain Ghana's beginnings. Some of these writers thought the rulers might have come from a different background, perhaps linking them to people from North Africa. Later, some French officials also suggested that Ghana was founded by people from outside the region.

However, most modern historians and archaeologists disagree with these ideas. They point out that earlier Arab writers, like al-Bakri in the 11th century, described the people and rulers of Ghana as Black Africans. Many scholars now believe that the empire had local African origins.

What Archaeology Tells Us

Since the mid-20th century, new archaeological discoveries have helped us understand Ghana's beginnings. These findings, combined with old writings and oral stories, suggest that the empire grew from local African cultures. For example, excavations at a place called Dhar Tichitt show a complex society existed there as early as 1600 BCE.

It seems that the Ghana Empire developed from many small farming and herding communities of the Mande people. These communities lived in the Niger River area for over a thousand years. As the desert grew, these groups moved south, bringing their skills in trade and ironworking, which were very important for building the new state.

Some historians, like Dierk Lange, suggest that the first capital of Wagadu might have been closer to Lake Faguibine, a more fertile area. They believe that conflicts in the 11th century might have caused the capital to move west.

The Empire's Journey Through Time

How Ghana Grew Strong

Around the 3rd century AD, a wetter climate in the Sahel made more land suitable for people to live and farm. This helped the Wagadu kingdom grow from the earlier Tichitt culture. The introduction of the camel to the Sahara Desert around the same time was a huge change. Camels made it much easier to travel and trade across the desert.

By the 7th century, camel routes connected North Africa with the Niger River. The Soninke people, who founded Ghana, were known for their strong warriors on horseback. They expanded their territory and population. Ghana became rich by controlling the trade of gold going north and salt going south. They didn't control the gold mines themselves, but they managed the trade routes. This control helped many smaller groups join together into a larger, powerful state.

Old records mention that many kings ruled Ghana before and after the arrival of Islam.

Changes and Challenges

Information about Ghana at its peak is limited. However, it's known that Ghana extended its influence over important trade towns like Awdaghost between 970 and 1054. Oral traditions suggest the empire controlled a vast area, including regions like Takrur, Diafunu, and Gajaaga.

As the Sahel region became drier, important trade centers began to shift south and west. This change gradually strengthened Ghana's smaller states while weakening the main empire. In 1054, the city of Awdaghost, a royal seat, was taken by the Almoravids, a powerful group from North Africa.

After King Ghana Bassi died in 1063, there might have been disagreements over who would rule next. This gave the Almoravids a chance to get involved, supporting leaders who favored Islam.

Ghana's Comeback

Many historians once believed the Almoravids completely conquered Ghana around 1076–77. However, modern scholars now question this idea. They suggest there might have been political influence or conflicts, but not a full military takeover that destroyed the empire. Archaeological findings don't show signs of widespread destruction from that time.

Whether conquered or not, the Ghana Empire did convert to Islam around 1076. This change in religion might have led to the spread of Soninke traders, known as Wangara, across the region. By 1083, Ghana, with Almoravid support, attacked other cities, helping to spread Islamic teachings.

By 1154, a writer named al-Idrisi described Ghana as a strong Muslim empire, just as powerful as it had been decades earlier. He called its capital "the greatest of all towns of the Sudan" for its size, population, and trade. During this time, the now-Islamic rulers regained control over many areas that had become independent. Ghana controlled a large trade network in the Senegal River valley, especially for salt from Awlil and gold from the mines of Bambuk. The legal system also began to follow Islamic law, known as Sharia.

The Sosso Take Over

This period of strength did not last forever. By 1203, a group called the Sosso rose up and conquered Ghana. Oral historians connect the arrival of Islam with the final end of Ghana. They say that when a Muslim ruling family came to power, they killed Bida, the sacred snake that protected the kingdom. This led to a seven-year drought, which devastated the kingdom and forced many people to leave.

Later stories from the 19th and 20th centuries say that Diara Kante took control of the capital, Koumbi Saleh. His son, Soumaoro Kante, then ruled and demanded tribute from the people. The Sosso also took over the neighboring Mandinka state of Kangaba, which had important goldfields.

Becoming Part of the Mali Empire

The historian Ibn Khaldun wrote that the people of the Mali Empire grew very powerful and took over the region. They defeated the Sosso and gained control of their lands, including Ghana. According to tradition, this rise of Mali was led by Sundiata Keita, the founder of the Mali Empire. Many historians believe this happened around 1230.

This tradition says that Ghana's ruler, Soumaba Cisse, who was then under Sosso control, rebelled and joined a group of Mande-speaking states. After the Sosso leader Soumaoro was defeated in the Battle of Kirina around 1235, the new rulers of Koumbi Saleh became allies of the Mali Empire. As Mali grew stronger, Ghana's role changed from an ally to a state that was part of the larger Mali Empire. However, Ghana was still respected as an ancient and important kingdom.

The city of Koumbi Saleh was eventually abandoned sometime in the 15th century.

Ghana's Economy: Gold, Salt, and Trade

Most of what we know about Ghana's economy comes from al-Bakri. He noted that merchants had to pay taxes on goods. For example, they paid one gold coin for every import of salt and two gold coins for every export of salt. Other goods, like copper, also had set taxes. However, there is no evidence that gold itself was taxed.

Ghana likely exported textiles, ornaments, and other crafted materials. Many fine leather goods found in Morocco at the time actually came from the Ghana Empire. Al-Bakri also mentioned that Muslims played a key role in trade and held important positions in the government.

The main trading hub was Koumbi Saleh. The king claimed all large pieces of gold for himself, allowing others to only have "gold dust." The empire also received tribute from various smaller states and chiefdoms around its borders. The use of camels was crucial for the Soninke's success, making it much easier to transport goods across the Sahara Desert. These factors helped the empire maintain a rich and stable economy based on trading gold, iron, salt, and other goods, including people. In its later years, Ghana lost some control of the gold trade to the Mali Empire and relied more on trading people as a main economic activity.

How the Ghana Empire Was Governed

Kingship in Ghana was based on matrilineal descent, meaning the throne traditionally passed to the son of the king's sister. This was different from many other kingdoms where power passed from father to son.

Islamic writers often praised the stability of the empire and the fairness of its king. Al-Bakri, an 11th-century scholar, described the king's court:

He sits in audience or to hear grievances against officials in a domed pavilion around which stand ten horses covered with gold-embroidered materials. Behind the king stand ten pages holding shields and swords decorated with gold, and on his right are the sons of the kings of his country wearing splendid garments and their hair plaited with gold. The governor of the city sits on the ground before the king and around him are ministers seated likewise. At the door of the pavilion are dogs of excellent pedigree that hardly ever leave the place where the king is, guarding him. Around their necks they wear collars of gold and silver studded with a number of balls of the same metals.

Ghana seemed to have a central core region surrounded by smaller states that paid tribute. Early sources mention that the king had authority over several other "kings," suggesting a network of smaller rulers under Ghana's main king. These smaller rulers likely governed different areas, often called kafu.

The Arabic sources don't give many details about how the country was managed day-to-day. Al-Bakri, however, noted that the king had officials who helped him deliver justice. These officials included the sons of the "kings of his country." Al-Bakri's writings also show that Ghana was surrounded by independent kingdoms, and some, like Sila on the Senegal River, were almost as powerful as Ghana itself.

By al-Bakri's time, Ghana's rulers had started to include more Muslims in their government, such as the treasurer, his interpreter, and many other officials. Kings were buried in large mounds, called tumuli, after lying in state for several days. They were buried with their personal belongings and offerings.

Koumbi Saleh: The Capital City

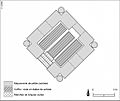

A 17th-century historical record from Timbuktu, the Tarikh al-fattash, named the empire's capital as "Koumbi." According to Al-Bakri's description from 1067/1068, the capital was actually made up of two cities about 6 miles (10 km) apart. However, there were continuous homes between them, making them seem like one large city. Most historians believe this capital was the site of Koumbi Saleh on the edge of the Sahara Desert.

The King's City (El-Ghaba)

Al-Bakri described one main part of the city as El-Ghaba, which was where the king lived. It was protected by a stone wall and served as the royal and spiritual heart of the Empire. It had a sacred grove of trees where priests lived, the king's grand palace, and other domed buildings. There was also one mosque for Muslim visitors. (Interestingly, El-Ghaba means "The Forest" in Arabic.)

The Muslim Quarter

The name of the other part of the city is not known. It had wells with fresh water for growing vegetables. This area was mostly inhabited by Muslims, who had twelve mosques, including one for Friday prayers. It was home to many scholars, scribes, and Islamic judges. Since most of these Muslims were merchants, this part of the city was likely its main business district. These inhabitants were probably the Soninke Wangara, who are now known as the Jakhanke or Mandinka. Having separate towns outside the main government center was a common practice for the Jakhanke people throughout history.

Digging Up the Past

French archaeologists began excavating the site of Koumbi Saleh in the 1920s. There have been some debates about whether Koumbi Saleh is exactly the same city described by al-Bakri. The site was further excavated in 1949–50 and again in 1975–81. The remains at Koumbi Saleh are impressive, even though the royal town, with its large palace and burial mounds, has not been fully found.

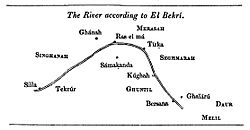

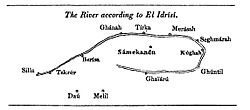

More recently, some scholars have questioned if Koumbi Saleh is truly the "city of Ghana" mentioned in old writings. al-Idrisi, a writer from the 12th century, described Ghana's royal city as being on a riverbank, which he called the "Nile." This was because people at the time often confused the Niger and Senegal Rivers, thinking they were one river called the "Nile of the Blacks." It's unclear if al-Idrisi was talking about a new capital built closer to the river, or if there was some confusion in his writings. He did mention that the royal palace he knew was built in 1116–1117 AD, suggesting it might have been a newer town.

Who Lived in Ghana?

The Ghana Empire was home to ancient Mande tribes. The Soninke tribe, part of the larger Mande ethnic group, brought these tribes together. The citizens lived in strong family groups and paternal clans.

Important Rulers of Ghana

Soninke Rulers ("Ghanas") of the Cisse Dynasty

- Kaya Magan Cissé (also known as Dinga Cisse)

- Dyabe Cisse: circa 790s

- Bassi: 1040–1062

- Tunka Manin: 1062–1076

Sosso Rulers

- Kambine Diaresso (sometimes also written as Jarisso): 1087–1090

- Suleiman: 1090–1100

- Bannu Bubu: 1100–1120

- Magan Wagadou: 1120–1130

- Gane: 1130–1140

- Musa: 1140–1160

- Birama: 1160–1180

Rulers During Kaniaga Occupation

- Diara Kante: 1180–1202

- Soumaba Cisse as vassal of Soumaoro Kanté: 1203–1235

Ghanas of Wagadou Tributary

- Soumaba Cisse as ally of Sundiata Keita: 1235–1240

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Imperio de Ghana para niños

In Spanish: Imperio de Ghana para niños

- History of the Soninke people

- Islam in Africa

- Mande People

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |