Koumbi Saleh facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Koumbi Saleh

|

|

|---|---|

|

Site of medieval town and Commune

|

|

| Country | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,484 km2 (573 sq mi) |

| Population

(census 2013)

|

|

| • Total | 11,064 |

| • Density | 7.4555/km2 (19.310/sq mi) |

Koumbi Saleh, also spelled Kumbi Saleh, is the site of an ancient ruined city in southeastern Mauritania. Many historians believe it was once the capital of the powerful Ghana Empire. Today, it is also a commune (a type of local government area) with a population of 11,064 people, based on the 2013 census.

Starting in the 800s, Arab writers began to mention the Ghana Empire. They connected it to the important trans-Saharan gold trade. An author named Al-Bakri, writing in the 1000s, described Ghana's capital as two towns. These towns were about 6 miles (10 km) apart. One town was home to Muslim traders, and the other was where the king of Ghana lived.

In 1913, a 17th-century African history book was found. It named the capital as Koumbi. This led French archaeologists to the ruins at Koumbi Saleh. Digs at the site have uncovered a large Muslim town. It had stone houses and a big mosque. However, no clear writing has been found to prove it was the capital of Ghana. The king's town described by al-Bakri has not yet been found. Scientists have used Radiocarbon dating on items from the site. This suggests people lived there between the late 400s and the 1300s.

Contents

Exploring the Ghana Empire's Capital in Old Texts

The first person to write about Ghana was a Persian astronomer, Ibrahim al-Fazari. He wrote in the late 700s, calling it "the territory of Ghana, the land of gold." The Ghana Empire was located in the Sahel region. This area is just north of West Africa's gold fields. The empire became rich by controlling the trade of gold across the Sahara desert. We don't know much about Ghana's early history. But there is proof that North Africa was buying gold from West Africa even before the Arab conquest in the mid-600s.

In old Arabic writings, the word "Ghana" could mean a royal title, a capital city, or a whole kingdom. The first time Ghana is mentioned as a town is by al-Khuwarizmi. He died around 846 AD. Two centuries later, al-Bakri gave a detailed description of the town. He wrote about it in his book, Book of Routes and Realms, finished around 1068. Al-Bakri never visited the region himself. He got his information from earlier writers and people he met in Spain.

Al-Bakri described the city of Ghana like this: The city had two towns on a flat plain. One town was large and had twelve mosques. Muslims gathered in one of these for Friday prayers. Nearby, there were wells with fresh water. People drank from these and used the water to grow vegetables. The king's town was about 6 miles (10 km) away. It was called Al-Ghāba. There were houses all the way between the two towns. The houses were made of stone and acacia wood. The king had a palace and several domed buildings. These were all surrounded by a wall, like a city wall. In the king's town, near his courts, there was a mosque for visiting Muslims to pray. Around the king's town were more domed buildings and groves. These were where the religious leaders lived.

The early Arab writers did not give enough details to find the exact spot of the town. Later, in the 17th century, an African history book called the Tarikh al-fattash said that the Malian Empire came after the Kayamagna dynasty. This dynasty had its capital at a town called Koumbi. Another important 17th-century book, the Tarikh al-Sudan, also said the Malian Empire followed the Qayamagha dynasty. This dynasty had its capital at the city of Ghana. People generally believe that the "Kayamagna" or "Qayamagha" dynasty ruled the Ghana Empire mentioned in the early Arabic sources.

Why Koumbi Saleh's Identity is Debated

In recent years, experts have started to question if Koumbi Saleh is truly the "city of Ghana" described in old writings. No clear writing has been found at the ruins that directly links them to the Muslim capital of Ghana. Also, the ruins of the king's town, Al-Ghaba, have not been discovered.

al-Idrisi, a writer from the 1100s, described Ghana's royal city as being on a riverbank. He called this river the "Nile." This was common back then, as people often mixed up the Niger and Senegal Rivers. They thought these rivers formed one big river, often called the "Nile of the Blacks." It's not clear if al-Idrisi was talking about a new capital somewhere else. Or if there was a mistake in his writings. However, he did say that the royal palace he knew was built in 1116–1117 AD. This suggests it was a newer town, built closer to a river than Koumbi Saleh. This has led some to think the capital might have moved south to the Niger River at some point.

In a French translation of the Tarikh al-fattash from 1913, Octave Houdas and Maurice Delafosse added a note. They said that local stories also suggested Koumbi was the first capital of Kayamagna. They noted the town was in the Ouagadou region of Mali. This was northeast of Goumbou, on the road to Néma and Oualata.

Ann Kritzinger, after re-reading ibn Battuta and other Arab writers, has a different idea. She believes the archaeological site of Koumbi Saleh is actually the Berber town of Awdaghost. She thinks the true capital of the Ghana Empire was Djenne.

Exploring the Ancient Koumbi Saleh Site

How Archaeologists Discovered Koumbi Saleh

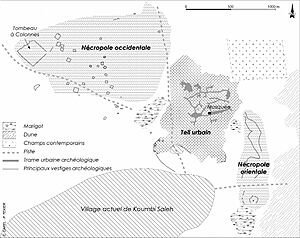

The large ruins at Koumbi Saleh were first reported by Albert Bonnel de Mézières in 1914. The site is in the Sahel region of southern Mauritania. It is about 30 km north of the border with Mali. The area has low grass, thorny bushes, and some acacia trees. During the wet season (July–September), rain fills some low areas. But for the rest of the year, there is no rain or surface water.

French archaeologists have been digging at the site for many years. Bonnel de Mézières started in 1914. Paul Thomassey and Raymond Mauny dug between 1949 and 1951. Serge Robert worked there in 1975-76, and Sophie Berthier in 1980–81.

What the City Looked Like

Koumbi Saleh was a well-planned city. Connah (2008) notes it had two main parts: the royal palace and the trading area. The palace was on a raised platform and had a moat around it. The trading area had a large central market and many smaller markets. These smaller markets sold specific types of goods. Insoll (1997) suggests the city's design was influenced by Islamic city planning. This included using mosques and orienting streets towards Mecca.

The main part of the town was on a small hill. Today, this hill is about 15 meters above the surrounding plain. The hill was likely lower in the past. Its current height is partly due to layers of old ruins. Houses were built from local stone (schist) using banco (a type of mud brick) instead of mortar. There is a lot of debris, suggesting some buildings had more than one floor. The rooms were quite narrow. This was probably because there were no large trees to provide long wooden beams for ceilings. Houses were built very close together, separated by narrow streets.

However, a wide avenue, up to 12 meters across, ran east to west through the town. At the west end was an open space, likely used as a marketplace. The main mosque was in the center of this avenue. It measured about 46 meters from east to west and 23 meters from north to south. The western end was probably open to the sky. The mihrab (a niche showing the direction of Mecca) faced directly east. The upper part of the town covered an area of 700 meters by 700 meters. To the southwest was a lower area (500 meters by 700 meters). This area likely had less permanent buildings and a few stone structures. There were two large cemeteries outside the town. This suggests people lived at the site for a long time. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal from a house near the mosque shows dates from the late 400s to the 1300s.

The Great Mosque of Koumbi Saleh

Architecture and History of the Mosque

The Kumbi Saleh mosque is thought to have been built between the 800s and 1300s. It is one of the oldest known mosques in the region, similar to those found in Adrar and Hodh. Even with limited historical records, these mosques are very important. They help us understand the ancient buildings of the area. In the 1000s, Al-Bakri identified Kumbi Saleh as the capital of the Kingdom of Wagadu, also known as the Kingdom of Ghana.

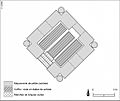

The Mosque of Kumbi Saleh was likely in a Sahelian steppe environment. It has been changed and expanded many times over its history. Original measurements suggest the building was about 46 meters long (east to west) and 23 meters wide (north to south). This made it one of the larger buildings of its time.

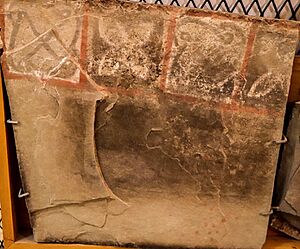

Raymond Mauny and Paul Thomassey first observed the mosque in 1950. Later, Serge Robert led extensive digs between 1979 and 1982. These digs gave important information about how the mosque was built over time. The mosque was mainly built of dry stone. It was decorated with red mud plaster. It also had decorative slate slabs with detailed painted designs. These designs included writings, geometric shapes, and flower patterns.

Throughout its existence, the Kumbi Saleh mosque went through several stages of growth and repair. Later additions raised the prayer hall's height to about 3 meters. Columns with stone drums on top supported the roof. Digs revealed several mihrabs. This shows the mosque was changed over time to meet the community's needs.

The many changes and additions to the mosque show how important Kumbi Saleh was. It was a lively cultural and religious center. The mosque of Awdaghust also shares many building features with the Kumbi Saleh mosque. Both used stone and had decorative elements. However, each mosque also had unique differences based on its own history.

World Heritage Status

The archaeological site of Koumbi Saleh was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List. This happened on June 14, 2001, in the Cultural category.

Images for kids