Martin Delany facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Martin Delany

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

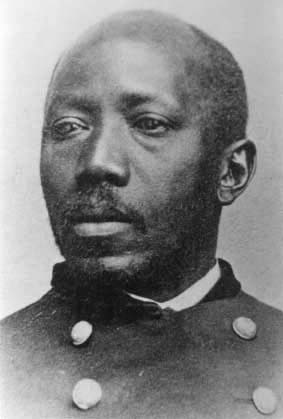

| Birth name | Martin Robison Delany |

| Born | May 6, 1812 Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia), U.S. |

| Died | January 24, 1885 (aged 72) Wilberforce, Ohio, U.S. |

| Buried |

Massies Creek Cemetery,

Cedarville, Ohio, U.S. |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1863–1865 |

| Rank | Major |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Spouse(s) | Catherine A. Richards |

Martin Robison Delany (May 6, 1812 – January 24, 1885) was an important American leader. He was an abolitionist, which means he worked to end slavery. He was also a journalist, a doctor, a soldier, and a writer. Many people see him as the first person to strongly support the idea of black nationalism. This is the belief that Black people should have their own strong communities and control their own future. Delany is famous for the Pan-African saying, "Africa for Africans." This idea means that African people should control their own continent.

Delany was born free in Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia). He grew up in Chambersburg and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He learned to be a doctor's assistant. During the cholera outbreaks in Pittsburgh in 1833 and 1854, he bravely treated sick people. Many other doctors and residents left the city because they were afraid of getting sick. At that time, people did not know how cholera spread.

In 1839, Delany traveled through the Southern states to see slavery for himself. From 1847, he worked with Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York. They published an anti-slavery newspaper called North Star. In 1850, Delany was one of the first three Black men accepted into Harvard Medical School. However, they were forced to leave after a few weeks because white students protested.

Delany dreamed of starting a Black settlement in West Africa. He visited Liberia, a country in Africa that was founded by Americans. He also lived in Canada for several years. When the American Civil War began, he returned to the United States. In 1863, when the United States Colored Troops (Black soldiers) were formed, he helped recruit men to join. In February 1865, Delany became a Major. This made him the first African-American field officer (a high-ranking leader) in the United States Army.

After the Civil War, Delany moved to South Carolina. He worked for the Freedmen's Bureau, which helped formerly enslaved people. He also became active in politics. He ran for Lieutenant Governor as an Independent Republican but did not win. He was appointed as a judge, but he lost this job after a problem. Later, Delany changed his political party. He worked for the campaign of Democrat Wade Hampton III. Hampton won the 1876 election for governor. This election was known for white groups, like the Red Shirts, trying to stop Black Republican voters.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Delany was born free in Charles Town, Virginia. His mother, Pati, was a free woman. His father, Samuel, was enslaved. In Virginia, if a mother was free, her children were also born free. This was true even if the father was enslaved. All of Delany's grandparents were born in Africa. His father's parents were from the Gola people in modern-day Liberia. They were captured and brought to Virginia as slaves. Family stories say his grandfather was a chief who escaped to Canada for a while. He died fighting against slavery.

His mother Pati's parents were from the Mandinka people in West Africa. Her father was said to be a prince named Shango. He and his future wife, Graci, were captured and brought to America as slaves. Later, their owner gave them their freedom in Virginia. Shango returned to Africa, but Graci stayed with their only daughter, Pati. When Martin was very young, some people tried to enslave him and his sibling. His mother, Pati, walked 20 miles to a courthouse in Winchester. She successfully argued for her family's freedom, proving she was born free.

As he grew up, Delany and his siblings learned to read and write. They used a book called The New York Primer and Spelling Book. In Virginia, it was against the law to educate Black people. In September 1822, when the book was found, Pati moved her children. They went to Chambersburg in the free state of Pennsylvania. This was to make sure they stayed free and could continue learning. They had to leave their father, Samuel. But a year later, he was able to buy his freedom and joined his family.

In Chambersburg, young Martin kept learning. Sometimes he had to leave school to work because his family needed money. In Pennsylvania, Black students usually only went to elementary school. So, Delany taught himself by reading many books. In 1831, at age 19, he moved to the growing city of Pittsburgh. There, he went to the Cellar School of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He also became an apprentice to a white doctor.

Delany and three other young Black men were later accepted into Harvard Medical School. But they were forced to leave because white students protested. The white students reportedly asked the school to not allow Black students.

Marriage and Family Life

While living in Pittsburgh, Delany met Catherine A. Richards in 1843. They got married. Catherine's father was a successful food seller, and her family was one of the wealthiest in the city. Martin and Catherine had eleven children together. Seven of their children lived to be adults. The parents believed strongly in education, and some of their children went to college.

Work in Pittsburgh

Delany became involved with Trinity A.M.E. Church in Pittsburgh. This church offered classes for adults. It was part of the first independent Black church group in the United States. Soon after, he studied classics, Latin, and Greek with Molliston M. Clark. Clark had studied at Jefferson College. During a national cholera outbreak in 1832, Delany became an apprentice to Dr. Andrew N. McDowell. He learned medical methods like fire cupping and leeching. These were common ways to treat diseases back then. He continued to study medicine with Dr. McDowell and other doctors who opposed slavery.

Delany became more active in politics. In 1835, he went to his first National Negro Convention. These meetings were held every year in Philadelphia since 1831. He was inspired to create a plan for a "Black Israel" on the east coast of Africa.

In Pittsburgh, Delany started writing about public issues. In 1843, he began publishing The Mystery, a newspaper controlled by Black people. His articles were often printed in other places, like the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison's newspaper, The Liberator. In 1847, a speech Delany gave for Rev. Fayette Davis was shared widely. In 1846, he faced a problem when he was sued for writing bad things about someone. He had accused a Black man of being a slave catcher in The Mystery. Delany was found guilty and had to pay a large fine of $650. His white supporters in the newspaper business paid the fine for him.

In 1847, Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison visited Pittsburgh on an anti-slavery tour. They met with Delany. Later that year, Douglass and Garrison had disagreements about using violence to end slavery. Douglass also wanted a newspaper run only by African Americans. So, Delany and Douglass decided to create North Star. This newspaper would share the stories of African Americans from their own point of view. They started publishing it in Rochester, New York, where Douglass lived. Douglass managed the editing and printing. Delany traveled to give speeches, report news, and get people to subscribe.

In July 1848, Delany reported in the North Star about a court case. A judge had told a jury that it was a crime to stop someone from taking back an enslaved person who had run away. Delany's reporting helped convince Salmon P. Chase, an abolitionist, to work against the judge becoming president.

Medicine and Black Nationalism

While in Pittsburgh, Delany studied medicine with doctors. He started his own practice, using cupping and leeching. In 1849, he began to study more seriously to apply to medical school. In 1850, he was accepted into Harvard Medical School. He had letters of support from seventeen doctors. Delany was one of the first three Black men to be accepted there. However, a month after he arrived, white students complained. They wrote to the school, saying that having Black students was bad for the school.

Within three weeks, Delany and the other two Black students were dismissed. This happened even though many students and staff supported them. Delany was very angry and returned to Pittsburgh. He became convinced that white leaders would not let Black people become leaders in society. His ideas became stronger. In his 1852 book, The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States, Politically Considered, he argued that Black people had no future in the United States. He suggested they should leave and create a new nation somewhere else, perhaps in the West Indies or South America. Some abolitionists who had more moderate views did not agree with him. Delany also strongly criticized separation among Freemasons, a social group.

Delany worked for a short time as a principal at a school for Black children. Then he started working as a doctor. During a serious cholera outbreak in 1854, most doctors left the city. Many residents who could leave also did so. No one knew what caused the disease or how to stop it. Delany stayed with a small group of nurses and cared for many sick people.

Delany is not often mentioned when people talk about African-American education. This might be because he did not focus mainly on starting schools or writing a lot about Black education.

Emigration to Africa

Delany had heard stories about his parents' ancestors. He wanted to visit Africa, which he felt was his spiritual home.

In August 1854, Delany led the National Emigration Convention in Cleveland, Ohio. He worked with his friend James Monroe Whitfield, a poet who opposed slavery, and other Black activists.

Delany presented his idea of emigration in his second important writing. It was called "Political Destiny of the Colored Race on the American Continent." The 1854 convention agreed on a statement. It said: "As men and equals, we demand every political right, privilege and position to which the whites are eligible in the United States, and we will either attain to these, or accept nothing." Many women who attended also voted for this statement. It is seen as a key moment for the idea of black nationalism.

In 1856, Delany moved his family to Chatham, Ontario, Canada. They lived there for almost three years. In Chatham, he helped with the Underground Railroad. This was a secret network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom in Canada. He also helped prevent formerly enslaved people from being returned to the United States.

From 1859 to 1862, Delany published parts of his novel, Blake; or the Huts of America. This was in response to Harriet Beecher Stowe's anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1855). Delany's novel showed a rebel traveling through enslaved communities. He thought Stowe had shown enslaved people as too quiet. However, he praised her for showing how cruel Southern slave owners were. Today, experts praise Delany's novel as a good picture of Black culture. The first part of his novel was published in a magazine from January to July 1859. The rest was published from 1861 to 1862. It was not published as a full book until 1970, and some chapters are still missing.

In May 1859, Delany sailed from New York to Liberia. He wanted to see if a new Black nation could be started there. Liberia was a colony founded by the American Colonization Society to move free Black people out of the United States. He traveled for nine months. He signed an agreement with eight local chiefs in the Abeokuta region, which is in today's Nigeria. This agreement would let settlers live on "unused land." In return, the settlers would use their skills to help the community. It is not clear if Delany and the chiefs had the same understanding of land use. The agreement later ended because of fighting in the region. White missionaries also opposed it, and the American Civil War began.

In April 1860, Delany left Liberia for England. He was honored by the International Statistical Congress there. However, one American delegate walked out in protest. By the end of 1860, Delany returned to the United States. The next year, he started planning to settle in Abeokuta. He gathered a group of possible settlers and money. But Delany decided to stay in the United States to work for the freedom of enslaved people. So, the settlement plans fell apart.

Service in the Union Army

In 1863, Abraham Lincoln asked for people to join the army. Delany, who was 51 years old, gave up his dream of starting a new settlement in Africa. Instead, he began recruiting Black men for the Union Army. His efforts in Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Ohio helped thousands of men join. Many of them joined the new United States Colored Troops. His son, Toussaint Louverture Delany, served in the 54th Regiment. The elder Delany wrote to the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton. He asked to lead "all of the effective black men as Agents of the United States." But his request was not accepted. During the war, 179,000 Black men joined the U.S. Colored Troops. This was almost 10 percent of all who served in the Union army.

In early 1865, Delany met with President Lincoln. He suggested creating a group of Black soldiers led by Black officers. He believed they could help convince Southern Black people to join the Union side. The government had already said no to a similar idea from Frederick Douglass. But Lincoln was impressed by Delany. He called him "a most extraordinary and intelligent man." Delany became a major in February 1865. He was the first Black field officer in the U.S. Army. He reached the highest rank an African American would get during the Civil War.

Delany especially wanted to lead Black troops into Charleston, South Carolina. This city was a strong supporter of the Southern states leaving the Union. When Union forces captured the city, Major Delany was invited to a special ceremony. Major General Robert Anderson would raise the same flag over Fort Sumter that he had been forced to lower four years earlier. Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson and abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison and Henry Ward Beecher were also there. Major Delany had recruited Black people from Charleston to help rebuild three regiments of U.S. Colored Troops. He arrived at the ceremony with Robert Vesey, the son of Denmark Vesey. Denmark Vesey had been executed for planning a slave rebellion. Robert Vesey came on the Planter, a ship led by the formerly enslaved Robert Smalls. Smalls had taken over the ship during the war and sailed it to Union lines.

The next day, the city learned that President Lincoln had been killed. Delany continued with a planned political rally for the newly freed people in Charleston. Garrison and Senator Warner spoke at the rally. Soon after, Delany published an open letter to African Americans. He asked them to help create a memorial for "the Father of American Liberty." Two weeks later, Delany was scheduled to speak at another rally. The Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase was visiting. A journalist was surprised when Delany talked about bad feelings between Black freedmen and mixed-race people in Charleston. He said that two mixed-race men had told authorities about Denmark Vesey's rebellion plans in 1822. Delany said this instead of trying to bring the groups together.

After the war, Delany stayed in the Army for a short time. He served under General Rufus Saxton. He was later moved to the Freedmen's Bureau. He worked on Hilton Head. He surprised white officers by strongly supporting giving land to formerly enslaved people. Later in 1865, Delany left the Freedmen's Bureau and soon resigned from the Army.

Later Life and Legacy

After the war, Delany continued to be active in politics. In 1871, he started a business that helped people buy and sell land. He worked to help Black cotton farmers improve their business skills. He wanted them to get better prices for their crops. He supported the Freedman's Savings Bank and also traveled and spoke for the Colored Conventions Movement. Delany also spoke out against some white politicians and Black candidates when he thought it was right. For example, he opposed some Black candidates for important jobs because he felt they were not experienced enough.

Delany tried to get various jobs, like being a Consul General to Liberia, but he was not successful. In 1874, Delany ran for Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina as an Independent Republican. Their ticket lost to the Republican candidates.

Delany was appointed as a judge in Charleston. In 1875, he was accused of "defrauding a church." He was found guilty and had to resign. He also spent time in jail. The Republican Governor pardoned him, but Delany was not allowed to return to his judge position.

Delany supported the Democratic candidate Wade Hampton III in the 1876 election for governor. He was the only well-known Black person to do so. Partly because of Black votes encouraged by Delany, Hampton won the election by a small number of votes. However, the election was unfair. White groups used threats and violence against Black Republicans to stop them from voting. Armed groups like the Red Shirts openly tried to stop Black voting. By 1876, these groups had about 20,000 white members in South Carolina. More than 150 Black people were killed in violence related to the election.

In early 1877, the federal government removed its soldiers from the South. This ended the period called Reconstruction. Governor Chamberlain left the state. The Democrats took control of South Carolina's government. Groups like the Red Shirts continued to stop Black people from voting, especially in some areas.

Because white people were regaining power and Black voting was being stopped, Black people in Charleston started planning to move to Africa again. In 1877, they formed the Liberia Exodus Joint Stock Steamship Company. Delany was the chairman of the finance committee. A year later, the company bought a ship, the Azor, for the journey.

Last Years and Death

In 1880, Delany stopped working on the emigration project to help his family. Two of his children were students at Wilberforce College in Ohio and needed money for school. His wife was working as a seamstress to earn money. Delany began practicing medicine again in Charleston. On January 24, 1885, he died of tuberculosis in Wilberforce, Ohio.

Delany is buried in a family plot at Massies Creek Cemetery in Cedarville, Ohio. His wife Catherine, who died in 1894, is buried next to him. For over 120 years, his grave only had a small government-issued tombstone with his name misspelled. Three of his children were also buried there, but their graves were unmarked. In 2006, after many years of raising money, The National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center raised $18,000. They used this money to build and place a monument at the grave site of Delany and his family. The monument is made of black granite from Africa. It has a picture of Delany in his army uniform.

Honors and Legacy

Historian Benjamin Arthur Quarles said that Delany's most special quality was his deep pride in his race.

- In 1853, the abolitionist poet James Monroe Whitfield dedicated his book "America and other poems" to Delany.

- In 1991, the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission placed a historical marker near 5 PPG Place in Pittsburgh. This marker honored Delany's importance near where he published The Mystery. In 2003, a second historical marker was placed on Main Street in Chambersburg.

- In 1999, a group called Star Lodge #1 of the Prince Hall Masons put up a historical marker in Charles Town to honor Delany.

- In 2002, the scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Delany as one of the 100 Greatest African Americans.

- In 2017, the West Virginia Legislature voted to name a new bridge over the Shenandoah River the "Major Martin Robison Delany Memorial Bridge."

- A statue of Delany greets visitors at the From Slavery to Freedom exhibit at the Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Works by Martin Delany

- The Origins and Objects of Ancient Freemasonry: Its Introduction into the United States and Legitimacy among Colored Men (1853)

- Political Destiny of the Colored Race on the American Continent (1854)

- Introduction to William Nesbitt, Introduction to Four Months in Liberia (1855)

- University Pamphlets: A Series of Four Tracts on National Policy (1870)

- Principia of Ethnology: The Origin of Races and Color, with an Archaeological Compendium of Ethiopian and Egyptian Civilization (1879)

See also

In Spanish: Martin Delany para niños

In Spanish: Martin Delany para niños

- List of African-American abolitionists

- Thornton Chase, a white officer in the 104th USCI

Images for kids

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |