Ranavalona I facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ranavalona I |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Queen of Madagascar | |||||

| Reign | August 11, 1828 – August 16, 1861 | ||||

| Coronation | August 12, 1829 | ||||

| Predecessor | Radama I | ||||

| Successor | Radama II | ||||

| Prime Ministers | Andriamihaja Rainiharo Rainivoninahitriniony |

||||

| Born | 1778 Ambatomanoina, Merina Kingdom |

||||

| Died | August 16, 1861 (aged 82–83) Manjakamiadana, Rova of Antananarivo |

||||

| Burial | 1861/1893 (re-interred) Ambohimanga/Tomb of the Queens, Rova of Antananarivo (re-interred) |

||||

| Spouse |

|

||||

| Issue | Radama II | ||||

|

|||||

| Dynasty | Hova dynasty | ||||

| Father | Prince Andriantsalamanjaka (also called Andrianavalontsalama) | ||||

| Mother | Princess Rabodonandriantompo | ||||

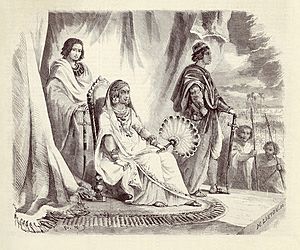

Ranavalona I (born Rabodoandrianampoinimerina, also known as Ramavo; around 1778 – August 16, 1861) was the Queen of the Kingdom of Madagascar from 1828 to 1861. She became queen after her husband, Radama I, passed away.

Queen Ranavalona I wanted Madagascar to be strong and independent. She decided to reduce connections with European countries. She also stopped a French attack on the town of Foulpointe. During her rule, she worked to stop the growing Christian movement in Madagascar.

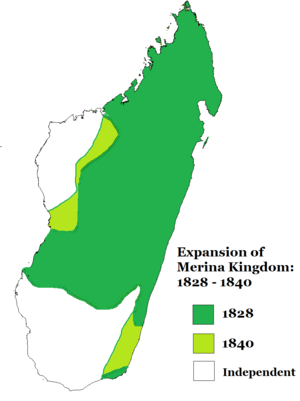

She used a traditional system called fanompoana, which was forced labor instead of paying taxes. This helped her build big projects and create a strong army of 20,000 to 30,000 soldiers. These soldiers helped her expand her kingdom across the island. Her 33-year reign was a time of many changes and challenges for Madagascar.

Even though Ranavalona I limited foreign influence, European countries were still interested in Madagascar. Some people in her court wanted closer ties with Europe, while others preferred traditional ways. This led to some attempts by Europeans to help her son, Radama II, become king sooner. Prince Radama II had different ideas from his mother. He even signed an agreement with a French representative in 1855, called the Lambert Charter, which would have allowed France to use the island's resources. However, these plans did not work out, and Radama II only became king after his mother's death in 1861.

For a long time, Western writers described Ranavalona I as a harsh ruler. But more recent studies see her as a strong queen who worked hard to protect Madagascar's independence and culture from European control.

Contents

Princess Ramavo was born in 1778 in Ambatomanoina, about 16 kilometers east of Antananarivo. Her parents were Prince Andriantsalamanjaka and Princess Rabodonandriantompo.

When Ramavo was young, her father warned King Andrianampoinimerina (1787–1810) about a plot to harm him. In return for saving his life, the king promised Ramavo to his son, Prince Radama, who was set to become king. The king also said that any child born to Ramavo and Radama would be next in line to the throne after Radama.

Ramavo was one of Radama's wives, but she did not have any children with him. When King Andrianampoinimerina died in 1810, Radama became king. It was a royal custom to remove potential rivals, and Radama did this to some of Ramavo's relatives. This might have made their relationship difficult. Ramavo spent time with missionaries like David Griffiths, and they became good friends.

King Radama I died on July 27, 1828, without any children. According to tradition, his nephew, Rakotobe, should have been the next king. Rakotobe was a smart young man and was one of the first students at the first school set up by the London Missionary Society in Antananarivo.

Radama's trusted advisors, who supported Rakotobe, waited a few days to announce the king's death. During this time, a military officer named Andriamamba found out the truth. He worked with other powerful officers to support Ramavo's claim to the throne.

These officers kept Ramavo safe and gained the support of important people, including judges and guardians of the royal idols called sampy. They also got the army to support Ramavo. So, on August 11, 1828, Ramavo announced herself as the new queen, saying that Radama himself had chosen her. She took the royal name Ranavalona. To secure her position, she removed her political rivals, including Rakotobe and his family. Her coronation ceremony took place on June 12, 1829.

Ranavalona was the first female ruler of the Kingdom of Imerina since it began in 1540. In her culture, men were usually favored for political power. However, rulers had the power to bring new ideas. Even though women had ruled in earlier times, this tradition had changed in the central highlands.

Ranavalona's 33 years as queen were focused on making her kingdom stronger and keeping Madagascar independent. She ruled during a time when European countries wanted more influence on the island. Early in her reign, she slowly pulled Madagascar away from European powers. She ended a friendship treaty with Britain and limited the activities of missionaries from the London Missionary Society. These missionaries ran schools that taught basic education and trade skills, as well as Christianity. In 1835, she made it illegal for Malagasy people to practice Christianity, and most foreigners left within a year.

The queen wanted Madagascar to be self-sufficient, meaning it could provide for itself. She did this by using fanompoana, a long-standing tradition of forced labor instead of tax payments. Ranavalona also continued the military campaigns started by Radama I to expand her kingdom across the island. She was strict with those who went against her wishes. These policies, along with wars and difficult labor, led to a decrease in the population during her rule.

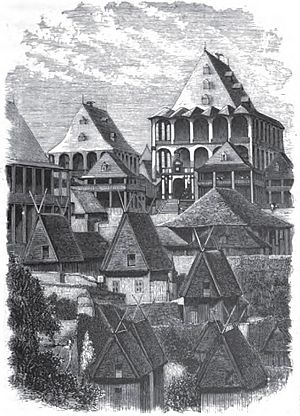

Queen Ranavalona ruled from the royal Rova compound in Antananarivo, just like many rulers before her. Between 1839 and 1842, a Frenchman named Jean Laborde built her a new home called Manjakamiadana. This became the largest building on the Rova grounds. It was made entirely of wood, like traditional Merina aristocratic homes, but also had European features like three floors and verandas. This palace was later covered in stone in 1867. Sadly, the original wooden palace was destroyed in a fire in 1995.

Ranavalona's rule continued many of the ways Radama I had governed. Both rulers welcomed new technologies and knowledge from other countries. They also supported building up industries and making the army more professional. They were careful with foreigners, using their skills but also setting rules to prevent big changes to Malagasy culture and politics. They both helped create a complex government system to rule the large island.

Ranavalona relied on advisors, mostly from the noble class. Her most powerful ministers were also her husbands. Her first chief advisor was Andriamihaja. He was likely the father of her only son, Prince Rakoto (who later became King Radama II). Andriamihaja wanted to keep good relations with Europe. However, other advisors, like Rainiharo, preferred traditional ways. They worked to reduce Andriamihaja's influence, and he was eventually replaced.

After Andriamihaja, Rainiharo became a very powerful advisor. Ranavalona married him in 1833. Rainiharo served as Prime Minister and Commander-in-Chief for many years. After he died, the queen married another advisor, Andrianisa (also called Rainijohary), who was Prime Minister until Ranavalona's death.

Traditionally, Merina rulers used public speeches called kabary to share their plans. Ranavalona preferred to send letters to her officials, which she dictated to scribes trained by missionaries. She also kept up traditional rituals, like the fandroana (new year ritual), to connect with her people and show her power.

Protecting and Expanding the Kingdom

Queen Ranavalona continued the military efforts started by Radama I. Her goal was to bring neighboring kingdoms under Merina rule and keep them loyal. This policy had a big impact on the population. The fanompoana system allowed the queen to have a large army of 20,000 to 30,000 soldiers. This army went on many expeditions to other provinces.

People who resisted Merina rule faced harsh consequences. Many were brought back to Imerina as slaves, and their valuable possessions were taken by the Crown. Wars and diseases like malaria also caused many deaths among soldiers.

The Tangena Ordeal

One way Ranavalona kept order was through a traditional test called tangena. This was a trial by ordeal where a person accused of a crime would be given a substance from the tangena plant. The outcome of this test was believed to show if they were innocent or guilty.

People in Madagascar could accuse others of various things, including theft or witchcraft. The tangena ordeal was often required for these accusations. If a person vomited up three pieces of chicken skin given with the substance, they were declared innocent. If not, they were considered guilty. People believed this ordeal was a form of divine justice.

The tangena ordeal was a dangerous practice. It was outlawed in 1863, but it continued secretly in some areas.

Limiting Christianity

After Radama I visited Madagascar's first school in 1818, he invited Christian missionaries to the capital. These missionaries taught skills like brick-making and carpentry. They also set up schools where students learned to read and write using parts of the Malagasy language Bible. While many attended the schools, few became Christian at first. Near the end of Radama's reign, he felt that some Malagasy Christians were not respecting royal authority. He then banned Malagasy people from being baptized or going to Christian services.

When Ranavalona became queen, there was a brief period where rules about Christianity were less strict. A printing press brought by missionaries was used to print thousands of hymnals and parts of the Bible. The New Testament was translated and distributed. Ranavalona allowed missionaries to use the press and even excused Malagasy workers at the press from military service. By 1835, the Old Testament was also translated. This freedom allowed Christianity to grow among a small group of people in the capital. Many people from different social classes became Christian.

However, the queen became worried about Christianity's effects. She saw it as leading Malagasy people away from their ancestors and traditions. In 1831, she banned Christian marriages, baptisms, and church services for soldiers and government workers. This ban was later extended to all Malagasy people. From 1832 to 1834, Christian practices continued, often in secret. Some Christians faced consequences, and Ranavalona asked some missionaries to leave, keeping only those with useful technical skills.

In a public speech on February 26, 1835, Queen Ranavalona officially made it illegal for her subjects to practice Christianity. She made it clear that this rule was for her own people, and practicing the new religion could lead to serious punishment. However, she allowed foreigners to practice their own religions. She also thanked European missionaries for sharing their knowledge and skills, asking them to continue helping Madagascar, but to stop trying to convert her people.

After this, many missionaries left Madagascar. Those who stayed to teach practical skills also left a year later. Malagasy people who had Bibles, went to church, or continued to be Christian faced fines, jail, or other punishments. Some were even executed. The Andohalo cathedral was later built to remember these early Malagasy Christians.

Protecting Madagascar's Independence

Ranavalona's reign was a time when France and Britain were trying to gain more influence in Madagascar. France wanted control of the main island, but Britain wanted to keep a safe route to India. Ranavalona wanted Madagascar to be independent and limit foreign power.

Soon after becoming queen, Ranavalona ended a treaty with Britain. She refused to accept yearly payments from Britain, which had been given in exchange for Madagascar stopping its involvement in the international slave trade. Ending this treaty meant Madagascar no longer received modern weapons from Britain. This made the queen vulnerable to attacks. In 1829, a French fleet attacked the fort of Foulpointe on the eastern coast. Ranavalona's army successfully pushed back the French.

The queen learned that a Frenchman named Jean Laborde, who had been shipwrecked in Madagascar, knew how to make cannons, muskets, and gunpowder. Ranavalona gave him workers and materials to build factories. This allowed her army to make its own weapons, so they didn't have to rely on Europe anymore.

The French were eager for Radama II to become king. This was because of the Lambert Charter, an agreement from 1855 between a French representative, Joseph-François Lambert, and Prince Radama. This agreement would only take effect when Radama became king and would give Lambert rights to use many of Madagascar's resources.

Lambert and others tried to get Radama II to sign a document that would lead to French military help. Radama was sympathetic to his people and wanted to ease their burdens, but he was suspicious. He reluctantly signed the document under pressure, not knowing it asked for French military intervention. France did not want to act without Britain's agreement. Radama, who had been sworn to secrecy, eventually told a British diplomat about the letter. The British refused to join the French plan, and an attack was avoided.

Since he couldn't get European support, Lambert decided to try a coup d'état (a sudden takeover of the government) on his own. He traveled to Ranavalona's court in May 1857 with Ida Pfeiffer, a famous traveler, who didn't know about the plot. Radama and Lambert planned to remove the queen on June 20. However, the plot failed. After it was discovered, the Europeans involved were told to leave Madagascar immediately.

Queen Ranavalona had chosen her son, Radama II, to be the next ruler. However, some conservative advisors wanted her nephew, Ramboasalama, to take the throne instead. But two brothers, Rainivoninahitriniony and Rainilaiarivony, who were powerful ministers, supported Radama. They made sure the army would support the prince. As Ranavalona was dying, Radama took steps to ensure he would become king without a fight.

On August 16, 1861, Ranavalona died in her sleep at the Manjakamiadana palace. To honor her, twelve thousand zebu (a type of cattle) were sacrificed, and their meat was given to the people. The official mourning period lasted nine months. Her body was placed in a silver coffin in a tomb at the royal city of Ambohimanga. During her funeral, an accident with gunpowder caused an explosion and fire, destroying some historic royal buildings. Later, in 1897, French authorities moved her body and the remains of other rulers to the tombs at the Rova of Antananarivo. Her son, Prince Rakoto, became King Radama II.

King Radama II, Ranavalona's son, quickly changed many of his mother's traditional policies. After Radama publicly became Christian, many people believed that Ranavalona's angry spirit was causing a widespread illness.

For a long time, people outside Madagascar saw Ranavalona as a harsh and cruel ruler. This view continued in Western history books until the 1970s. However, more recent historical studies often see her as a smart leader who successfully protected her country's independence and culture from European influence.

Today in Madagascar, people have different views of Ranavalona. Many still see her negatively, especially Malagasy Christians. But others admire her efforts to keep Malagasy traditions and independence strong. Most people, no matter what they think of her domestic policies, agree that she was a remarkable figure in Malagasy history and praise her strength as a ruler during a challenging time with European powers.

A fictional story about Ranavalona and her court appears in the novel Flashman's Lady by George MacDonald Fraser.

See also

In Spanish: Ranavalona I para niños

In Spanish: Ranavalona I para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |