History of the Marshall Islands facts for kids

The Marshall Islands were first settled by Austronesian people about 4,000 years ago. We don't have old stories or records from that time. Over many years, the Marshallese people became amazing sailors. They learned to travel long distances across the ocean using special walap canoes and unique stick charts.

Contents

Ancient Times

Studies of languages and cultures suggest the first settlers came from the Solomon Islands. Scientists found old cooking pits and other signs of life on Bikini Atoll. These findings suggest people lived there from 1200 BCE to at least 1300 CE. Similar discoveries on other islands show people lived there around the 1st century CE. For example, old cooking pits were found in Laura village on Majuro and on Kwajalein.

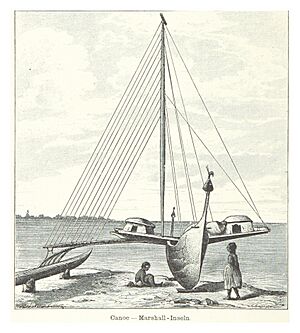

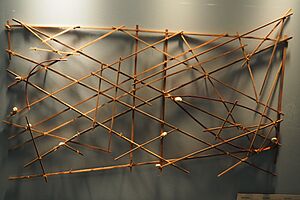

The Marshallese traveled between islands in special boats called proas. These boats were made from breadfruit tree wood and coconut fiber rope. They used the stars to find their way. But they also had a special way of reading ocean waves. They could tell where low coral islands were, even if they couldn't see them. The Marshallese knew about four types of waves. They noticed that waves would bend around the underwater slopes of islands. When bent waves from different directions met, they made special patterns. Marshallese sailors could "read" these patterns to find an island. Sailors also made stick charts to map these wave patterns. These charts were for teaching students and for planning trips. Sailors did not take them on their voyages.

The Austronesian settlers brought new plants and animals from Southeast Asia. These included coconuts, giant swamp taro, and breadfruit. They also brought domesticated chickens. The southern islands get more rain than the northern ones. So, people in the wet south ate a lot of taro and breadfruit. People in the north ate more pandanus and coconuts. Old digging sites have found tools like adzes and chisels made from shells. They also found jewelry, beads, fishhooks, and fishing lures made from shell and coral.

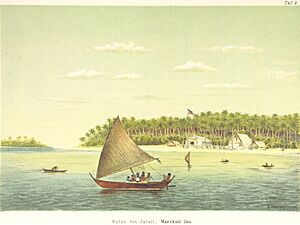

When Russian explorer Otto von Kotzebue visited in 1817, the islanders showed few signs of Western influence. They had some metal scraps and stories of passing ships. He saw that the Marshallese lived in huts with thatched roofs. The Marshallese had pierced ears and tattoos. Kotzebue noticed they kept women away from foreigners. The Marshall Islands had two main groups: the Ratak and Ralik chains. Each was ruled by a top chief, called an iroijlaplap. This chief had power over the individual island chiefs, called iroij.

European Explorers Arrive

Spanish Explorers

The first European to see the Marshall Islands was Spanish explorer Alonso de Salazar. This happened on August 21, 1526. He was leading the ship Santa Maria de la Victoria. His crew saw an island, which might have been Taongi. They could not land because of strong currents. Salazar named the island "San Bartolomé."

In late 1527, the Spanish ship Florida arrived. This was part of Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón's journey from Mexico. They likely saw several islands, including Utirik and Enewetak Atoll. Saavedra named them "Islas de los Reyes" (Islands of the Kings). Canoes from the islands came near the ship but did not make contact. On January 2, 1528, they landed on an empty island to get supplies. Saavedra's group sailed towards the Philippines on January 8.

On December 26, 1542, a fleet of six Spanish ships led by Ruy López de Villalobos saw an island in the Marshalls. They landed and named it "Santisteban." The island was lived on, but many people ran away. The Spanish found some women and children hiding and gave them gifts.

Miguel López de Legazpi led four Spanish ships from Mexico in November 1564. One ship, the San Lucas, sailed into the Marshall Islands. It passed Likiep and Kwajalein. On January 8, they saw Lib Island. This island was heavily populated. The Spanish described the people as warlike. So, the ship sailed on without landing. Meanwhile, Legazpi's other three ships arrived at Mejit on January 9, 1565. They found a village of one hundred people. Legazpi named the island "Los Barbudos" (The Bearded Ones).

By the late 1500s, Spanish ships usually avoided the Marshalls. They saw them as dangerous waters.

Later European Explorers

British ships Charlotte and Scarborough visited the islands in 1788. They were led by captains Thomas Gilbert and John Marshall. On June 25, 1788, the British ships traded with islanders at Mili Atoll. This might have been the first time Europeans and Marshallese met in over 200 years. Later maps were named after John Marshall.

From the 1790s, British trading ships began passing through the Marshall Islands. They mapped the islands they found. By 1815, most islands and atolls were mapped.

Russian explorer Otto von Kotzebue spent three months exploring the Ratak Chain in early 1817. He came back to explore again in 1824 and 1825. Kotzebue said the Marshallese showed few signs of Western influence on his first visit. He gave the islanders metal knives and hatchets. He also brought new crops like yams, and animals like pigs, goats, dogs, and cats. Kotzebue also noted that in 1817, Lamari, the top chief of Aur Atoll, had taken over other northern Ratak islands. He was planning to fight Majuro Atoll. On his later trips, Kotzebue found that the metal hatchets helped Lamari win against Majuro.

Early Colonial Period

In February 1824, the American whaling ship Globe stopped at Mili Atoll. The crew had rebelled and killed their officers. While the rebels were on shore, other crew members took the ship and left the rebels behind. Two years later, an American navy ship found that the rebels had been killed by the Marshallese. This was because the rebels had treated local women badly. Only two boys survived. The Marshallese had adopted them.

From the 1830s to the 1850s, Marshallese Islanders became more unfriendly to Western ships. This was likely because sea captains punished theft harshly. Also, Marshallese people were being kidnapped and forced to work on Pacific farms.

European and American missionaries and traders began peaceful contact with the Marshallese around 1850. This started at Ebon Atoll. More ships came to Ebon, bringing more foreigners. This also led to outbreaks of Western diseases. In February 1859, an influenza outbreak killed many common people on Ebon. In 1861, measles and influenza outbreaks happened. In 1863, a typhoid fever outbreak killed more islanders.

Missionaries Arrive

In 1855, American missionaries came to Micronesia. In November 1857, George Pierson and Edward Doane set up a mission on Ebon. Within a few years, the missionaries saw social changes on Ebon. Women were allowed to attend some religious events for the first time. Traditional burial customs started to disappear. Islanders also began to follow the Christian rule of not working on Sunday. By 1876, a traveler noticed that most Marshallese women on Ebon wore Western dresses. Many men wore trousers instead of traditional grass skirts.

Pierson and Doane later left. They were replaced by Native Hawaiian missionaries. These missionaries ran a school and printed Bibles in Marshallese. Ten Ebon islanders were baptized in 1863. This number grew to over 100 by 1870. By 1865, churches and schools had opened on Jaluit and Namdrik. Missions spread to Mili and Majuro in 1869. By the mid-1870s, most island churches were led by Marshall Islanders trained in the mission schools.

While many common people liked the church, Marshallese nobles became less friendly to Christianity. This happened after chief Kaibuke died in 1863. Many chiefs stopped church services. Some even hurt converts. Some historians think the nobles might have seen commoners learning to read and getting new information as a threat to their power.

Western Business Interests

In 1859, a German company sent traders to set up a trading post on Ebon Atoll. In 1861, they built a coconut oil factory there. In 1863, the company had money problems and left. One of the traders, Adolph Capelle, started his own trading company. He partnered with Anton Jose DeBrum. Both men married local women and became close with the islanders and missionaries. Their company, Capelle & Co., sold dried coconut meat, called copra, to a large German company. This German company exported copra to Europe. The German companies traded Western goods to Marshallese chiefs for coconuts. Marshallese commoners collected these coconuts as a payment to the chiefs.

In 1873, Capelle & Co. moved its main office to Jaluit. This was the home of Kabua, a powerful chief. Other companies also started trading copra in the Marshall Islands. This led to a price war, which was good for Marshallese suppliers. The companies also started selling things that were previously not allowed, like alcohol and guns.

By 1878, Hernsheim & Co. became the main company in the copra trade. Capelle & Co. bought all of Likiep Atoll to grow coconuts. This helped them control their copra supply and prices. By 1885, two German companies controlled two-thirds of the copra trade in the Marshall Islands.

Forced Labor

In the 1870s, some Marshall Islanders were forced to work on farms in other parts of the Pacific. This practice was called "blackbirding." Many of these workers died, and few returned home. This forced labor trade slowed down after the British government passed a law in 1872. But Jaluit continued to be a place where workers from other islands were taken.

Marshallese Politics

After chief Kaibuke died in 1863, his two nephews, Loiak and Kabua, argued over who should be the top chief of the southern Ralik Chain. Both chiefs tried to get support from foreigners. They befriended missionaries and worked with German copra traders to keep their power.

Their disagreement was peaceful for twelve years. But in September 1876, it almost turned violent. While both chiefs were on Ebon, a trader saw a group of Loiak's followers with guns. They were getting ready to attack Kabua's followers. Kabua fled to his land on Jaluit instead of fighting. In May 1880, Loiak's followers invaded Jaluit to challenge Kabua. The two groups met with guns but did not fight. No one was hurt.

In the late 1870s and 1880s, chiefs on Majuro and Arno Atolls also fought each other. On Majuro, chiefs Jebrik and Rimi fought for years. A British warship helped them make a peace treaty in 1883. These fights stopped copra production and caused hunger. This was because fighting groups destroyed their rivals' coconut trees. Copra traders started selling guns and ammunition to keep making money.

Western Countries Show Interest

In 1875, the British and German governments secretly talked about dividing the western Pacific. Germany got northeastern New Guinea and some islands in Micronesia, including the Marshall Islands. On November 26, 1878, a German warship arrived at Jaluit. It was there to start talks with the chiefs of the Ralik Chain. On November 29, the captain signed a treaty with Kabua and other Ralik Chain chiefs. This treaty gave the German Empire special trading rights. Germany got a place to refuel ships at Jaluit. The German authorities also recognized Kabua as the "King of the Ralik Islands."

The German Empire set up an office on Jaluit in 1880. Franz Hernsheim, from a German trading company, became the German representative. The United States made Adolph Capelle its representative to protect American missionaries.

German Control

German businesses asked their government to take over the Marshall Islands. The British government agreed to Germany taking the Marshalls. On August 29, 1885, German leader Otto von Bismarck allowed the Marshall Islands to become a German Protectorate. A protectorate means a stronger country protects and partly controls a weaker one.

On October 13, 1885, a German warship arrived at Jaluit. It was there to get chiefs to sign a protection treaty. On October 15, chief Kabua and four other chiefs signed a treaty. German soldiers raised the flag of the German Empire over Jaluit. The ship did similar ceremonies on seven other islands. The treaty made it seem like the chiefs asked for German protection. Some chiefs who favored America refused to recognize German power. They only agreed after being threatened by the German navy in mid-1886.

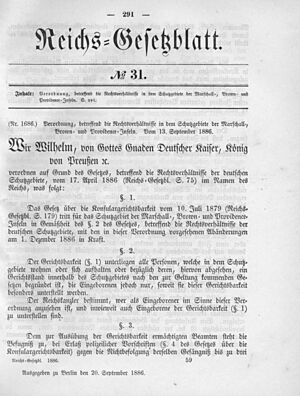

In September 1886, an order created the Protectorate of the Marshall Islands. It said that German laws would apply to everyone living there. In 1888, Nauru also became part of the Marshall Islands protectorate.

The Jaluit Company

The German leader Bismarck wanted private companies to run the colonies. Two German companies joined together in December 1887 to create the Jaluit Company. This new company started running the colony in January 1888. The company had the right to be asked about all new laws. It also chose all colonial staff. The company paid for the colony's costs. It collected fees from businesses and an annual tax. The tax system was based on the old tribute system. Chiefs collected taxes in copra for the company and kept one-third of the total.

The Jaluit Company was the most successful German colonial company. Its profits grew a lot. The company's fees pushed out American and British competitors. By 1901, the Jaluit Company had a monopoly, meaning it was the only one trading in the region. Other countries complained about the high fees. So, on March 31, 1906, the German government took direct control. The Marshall Islands and Nauru became part of German New Guinea. The Jaluit Company still made a lot of money from phosphate mining on Nauru.

Life Under German Control

During this time, most islanders learned to read and write Marshallese and do math. In 1898, 25 mission schools were operating with 1,300 students. German Catholic missionaries arrived in 1899. While few Marshallese became Catholic, their schools on Jaluit, Arno, and Likiep were popular. Catholic schools gave more years of education, including German language lessons.

German reports from this time noted that old Marshallese customs were disappearing. This was true except in remote northern islands. Most women wore dresses instead of traditional woven mats. Old crafts like stick charts were used less as Western products became available.

In 1900, Marshallese common people went on a general strike. They demanded higher pay from the Jaluit Company. The chiefs pressured most workers to return to work. But church groups on Mejit and Namdrik strongly resisted the company. The company lowered its buying price for copra. This made the islanders stop producing copra completely. The German authorities arrested seven strike leaders. They also blocked the islands from 1901 to 1904. The islanders held out, and the company doubled wages in 1904. Marshallese dockworkers on Jaluit had a similar successful strike in 1911. They also doubled their wages.

The Marshallese population dropped by more than 30% during the German control. It went from 13,000-15,000 people to 9,200 in 1908. A typhoon in 1905 killed about 200 people. Hundreds of islanders died from Western diseases. For example, dysentery outbreaks on Ebon killed many people in 1907 and 1908.

Japanese Control

When World War I started in August 1914, the United Kingdom and Empire of Japan were allies. Britain asked Japan for help against Germany. This gave the Imperial Japanese Navy a reason to invade Germany's Pacific colonies.

Japanese troops arrived at Enewetak on September 29, 1914, and Jaluit on September 30. In October, Britain and Japan agreed that Japan would handle operations north of the equator. This agreement put most of German Micronesia under Japanese military control. In February 1917, Britain and Japan secretly agreed that Japan would take over Micronesia after the war.

In January 1919, Japan asked to take over Germany's Pacific island colonies. United States President Woodrow Wilson was against this. He wanted a system of League of Nations mandates instead. A mandate meant a country would govern a territory on behalf of the League of Nations. The conference agreed to a compromise. Germany's Pacific colonies north of the equator became the Japanese South Seas Mandate. This was a Class C mandate. Because the islands were small and had few people, Japan could govern them as if they were part of Japan. Germany gave the Marshall Islands to Japan when the Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919.

The United States government and military did not like Japan taking over Germany's Micronesian colonies. They suspected Japan was secretly building up its military there.

How Japan Governed

In December 1914, the Japanese military created a temporary force to govern Micronesia. They set up their main office at Truk Atoll. The military divided Micronesia into six naval districts. The Marshalls district was governed from Jaluit. The Japanese were told to keep as many German-era laws as possible at first. But Japanese laws replaced German laws in 1915. The Japanese sent most German settlers and officials away in June 1915.

The military government stopped most foreign ships from stopping in Marshall Islands harbors. Non-Japanese foreigners had to apply many times to visit the islands.

Japanese scientists and experts studied Micronesia. They wanted to see how much money the islands could make. Their report said the islands were most valuable for their location. The Japanese adopted the German system of having local chiefs collect a tax in copra.

The Japanese navy left Micronesia in 1921. A civilian government, called the South Seas Government, took over. Its main office was in Koror, Palau. The Marshall Islands was one of six branch governments. The main office for the district stayed in Jaluit. The Japanese government had many more staff than the Germans. They also tried to weaken the chiefs. They stopped any chief from owning land on more than one island.

Life for Marshall Islanders Under Japan

The Japanese government tried to convince Micronesians that Japanese and Micronesian people were the same race. They encouraged the Marshallese to become more like the Japanese. In 1915, the military government started a three-year public school system. These schools taught in Japanese and slowly replaced the missionary schools. Students were not allowed to speak Marshallese in schools. More than half of school lessons were about Japanese language and culture. The government used boats to bring students from smaller islands to schools on larger islands. By 1935, going to public school was required for all children who lived near a school.

The government also supported youth groups. These groups focused on Japanese activities like track and field and baseball. Starting in 1915, important Marshall Islanders got free trips to Japan. This was to show them Japanese culture.

However, Japanese policies treated the Marshallese as second-class citizens. Schools for Marshallese students offered less education than schools for Japanese settlers. Few islanders could get jobs in the government. They also earned less money than Japanese settlers doing the same jobs.

Japanese Settlers and Development

The Marshall Islands produced the most copra in the Japanese mandate. Copra was the biggest industry in the Marshalls. Other industries also grew, including phosphorus mining on Ebon, and commercial tuna fishing and canning.

A Japanese company took over the copra trade. It was able to use and expand the trading system that German companies had built. The Japanese navy also gave this company a special right to transport military supplies and people. In 1918, the authorities tried to get more copra. They said that any land not planted with coconut trees within three years would become government property.

Japanese, Koreans, and people from Okinawa settled in the Marshall Islands. But they were one of the smallest groups of settlers. In 1937, about 500 immigrants lived in the Marshalls. Marshall Islanders remained the majority of the population. While cities grew a lot in other parts of the Japanese mandate, the main town of Jabor, Jaluit, grew more slowly. Even though the immigrant workforce was small, their presence caused wages in the Marshall Islands to drop.

Military Buildup

On March 27, 1933, Japan said it would leave the League of Nations. Japan officially left the League in 1935 but kept control of the islands. Japan began building up its military after its invasion of China in 1937. The Japanese navy returned to the South Seas Mandate that year. They started building civilian airfields. Military planners first thought the Marshalls were too far away and hard to defend. But as Japan developed long-range bombers, the islands became useful. In 1939 and 1940, the navy built airfields on Kwajalein, Maloelap, and Wotje Atolls. They also built seaplane bases at Jaluit. The navy also made ports in the Marshalls bigger and more modern. In February 1941, Japanese ships and troops began arriving to guard the newly fortified islands. The Japanese main office in the Marshalls was at Kwajalein.

The government forced hundreds of Korean workers to build the airfields and ports. Marshallese men were also forced to work in military camps.

World War II

When the Pacific War began, Japanese air raids and landing parties for the Battle of Wake Island started from Kwajalein. The Japanese invasions of the Gilbert Islands and Nauru both started from Jaluit. On February 1, 1942, the United States Pacific Fleet carried out the Marshalls–Gilberts raids. These attacks hit Jaluit, Kwajalein, Maloelap, and Wotje. They were the first American air raids on Japanese territory.

By 1943, the Japanese navy had built airfields on Enewatak and Mili Atolls.

The American invasion of the Marshall Islands began on January 31, 1944. This was during the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign. The Americans invaded Majuro and Kwajalein at the same time. By late 1944, the Americans controlled all of the Marshall Islands. Only Jaluit, Maloelap, Mili, and Wotje were still held by the Japanese. These Japanese-held islands were cut off from supplies and bombed by the Americans. The Japanese soldiers started running out of food in late 1944. This led to many deaths from hunger and sickness.

Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands

After being captured by the United States during World War II, the Marshall Islands became part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands in 1947. This was under the United Nations.

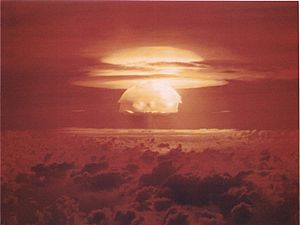

United States Nuclear Testing

From 1946 to 1958, during the early years of the Cold War, the United States tested 67 nuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands. This included the largest atmospheric nuclear test ever done by the U.S., called Castle Bravo. These bombs were very powerful. With the 1952 test of the first U.S. hydrogen bomb, called "Ivy Mike," the island of Elugelab in the Enewetak atoll was destroyed. In 1956, the United States Atomic Energy Commission said the Marshall Islands were "by far the most contaminated place in the world."

Discussions about nuclear claims between the U.S. and the Marshall Islands are still happening. The health effects from these nuclear tests continue. From 1956 to August 1998, at least $759 million was paid to the Marshallese Islanders. This was to help them because they were exposed to radiation from the U.S. nuclear weapon testing.

Independence

In 1979, the Government of the Marshall Islands was officially created. The country became self-governing.

In 1986, the Compact of Free Association with the United States began. This gave the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) its independence. The Compact provided money and U.S. defense for the islands. In return, the U.S. could continue to use the missile testing range at Kwajalein Atoll. The independence process was fully completed in 1990. The UN officially ended the Trusteeship status. The Republic joined the UN in 1991.

In 2003, the U.S. created a new Compact of Free Association for the Republic of the Marshall Islands. It included $3.5 billion in funding over the next 20 years.

A report in mid-2017 by Stanford University found that fish and plant life were plentiful in the coral reefs of Bikini Atoll. However, that area of the islands was still not safe for humans to live in due to radioactivity. A 2012 report by the United Nations had said that the contamination was "almost impossible to reverse."

In January 2020, David Kabua, the son of the first president, was elected as the new President of the Marshall Islands.

Climate Crisis

In 2008, very large waves and high tides caused widespread flooding in the capital city of Majuro. On Christmas morning in 2008, the government declared a state of emergency. In 2013, strong waves again broke through the city walls of Majuro.

In 2013, the northern islands of the Marshall Islands had a drought. This drought left 6,000 people with very little water. This caused food crops to fail and diseases like diarrhea to spread. These emergencies led the United States President to declare an emergency in the islands. This brought support from U.S. government agencies.

After the 2013 emergencies, the Minister of Foreign Affairs Tony deBrum was encouraged by the U.S. to use these crises to push for action against climate change. DeBrum asked for new commitment and international leadership to stop more climate disasters from hitting his country. In September 2013, the Marshall Islands hosted a big meeting. DeBrum proposed a Majuro Declaration for Climate Leadership. This was to encourage real action on climate change.

Rising sea levels are threatening the islands. Some may become unlivable if sea levels keep rising. Major flooding happened in 2014. Thousands of islanders have already moved to the U.S. over the past decades. They go for medical treatment, better education, or jobs. More people are likely to move as sea levels rise. The United States Geological Survey warned in 2014 that rising sea levels will make the fresh water on the islands salty. This will likely force people to leave their islands in decades.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de las Islas Marshall para niños

In Spanish: Historia de las Islas Marshall para niños

- List of colonial governors of the Marshall Islands

- List of United States National Historic Landmarks in United States commonwealths and territories, associated states, and foreign states#NHLs in associated states

- National Register of Historic Places listings in the Marshall Islands

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |