Australian Senate facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Senate |

|

|---|---|

| 48th Parliament of Australia | |

|

|

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

|

Sue Lines, Labor

Since 26 July 2022 |

|

|

Leader of the Government

|

|

|

Manager of Government Business

|

|

|

Leader of the Opposition

|

|

|

Manager of Opposition Business

|

Jonathon Duniam, Liberal

Since 25 January 2025 |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 76 |

|

|

|

Political groups

|

Effective 1 July 2022 Government (26) |

|

Length of term

|

6 years (state senators) 3 years (territory senators) |

| Elections | |

| Proportional representation (single transferable vote) | |

|

Last election

|

3 May 2025 (Half Senate election) |

|

Next election

|

On or before 20 May 2028 |

| Meeting place | |

|

|

| Senate Chamber Parliament House Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia |

|

The Senate is one of the two houses of the Parliament of Australia. It is known as the upper house. The other house is the House of Representatives, which is called the lower house. For a new law to be passed, it must be approved by both houses. The Senate's main job is to review laws and represent the interests of Australia's states and territories.

The rules for the Senate are written in the Constitution of Australia. The Senate is made up of 76 members, called senators. Each of Australia's six states elects 12 senators. The Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory each elect two senators. This means that states with fewer people have the same number of senators as states with many people, giving them a powerful voice in parliament.

The Senate has nearly the same amount of power as the House of Representatives. However, it cannot introduce new laws about taxes or government spending. The Senate plays an important role in checking the work of the government and making sure new laws are fair and well-made.

Contents

What is the Senate's Job?

The creators of the Australian Constitution wanted the Senate to be an active and powerful part of parliament. They looked at two different systems for ideas. One was the British Westminster system, where the upper house mainly reviews laws. The other was the United States Senate, where every state gets equal representation.

Australia's Senate is a mix of both, which is sometimes called a "Washminster system". This means it acts as a "house of review," carefully checking all proposed laws. It also makes sure that states with smaller populations have a strong voice in the national parliament.

In practice, most new laws are started by the government in the House of Representatives. The bill then goes to the Senate. The Senate can approve the bill, suggest changes (amendments), or reject it completely. This process helps improve laws and ensures many different viewpoints are considered.

The Senate also has many committees. These are small groups of senators who investigate important topics, like health or the environment. They hold meetings, gather information, and write reports to help the parliament make good decisions.

How Are Senators Elected?

The way senators are elected has changed over time. Today, Australia uses a system called proportional representation with a single transferable vote. This system is designed to be very fair. It means that the number of seats a political party wins in the Senate is closely related to the percentage of votes it gets.

This voting system has helped smaller political parties and independent candidates get elected. As a result, the government often does not have a majority of senators. This means the government must work with other parties to pass its laws. This is called having the balance of power.

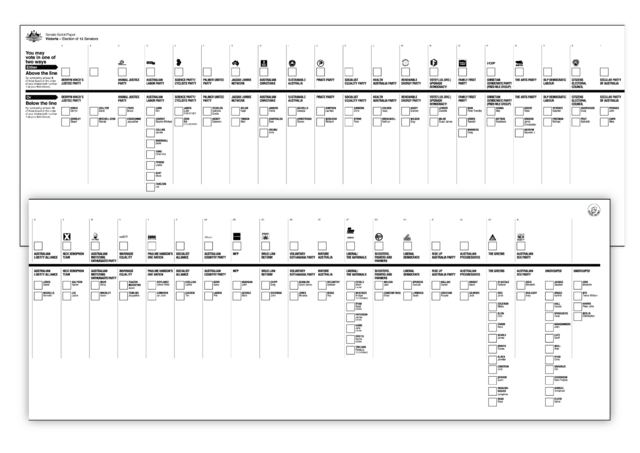

The Ballot Paper

When people vote for the Senate, they get a very large ballot paper. It lists all the candidates and their political parties. Voters have two choices:

- Vote "above the line": Voters can number at least six boxes for the parties they prefer. The party then decides how the vote is passed on to its candidates.

- Vote "below the line": Voters can number at least twelve boxes for the individual candidates they prefer, in any order they like.

This system gives voters a lot of control over where their vote goes.

Who Can Be a Senator?

The Constitution sets out the rules for the Senate's membership.

Size and State Representation

A key rule of the Senate is that every original state must have the same number of senators. This is to protect the smaller states from being overpowered by the larger ones. For example, Tasmania, with about 550,000 people, elects 12 senators, the same number as New South Wales, which has over 8 million people.

The Constitution also says that the House of Representatives should have, as much as possible, twice the number of members as the Senate. This is known as the "nexus".

The table below shows how many people each senator represents in each state and territory.

| State/Territory/Commonwealth | 2021 Census population | Population per senator |

|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | 8,339,347 | 694,945 |

| Victoria | 6,503,491 | 541,957 |

| Queensland | 5,156,138 | 429,678 |

| Western Australia | 2,660,026 | 221,668 |

| South Australia | 1,781,516 | 148,459 |

| Tasmania | 557,571 | 46,464 |

| Northern Territory (including Christmas Island and Cocos (Keeling) Islands) | 234,890 | 117,445 |

| Australian Capital Territory (including Jervis Bay Territory and Norfolk Island) | 456,687 | 228,343 |

| Australia | 25,422,788 | 334,510 |

Terms of Service

Senators from the states are usually elected for a six-year term. The terms are staggered, so at most federal elections, only half of the state senators are up for election. This is called a "half-Senate election".

Senators from the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory have shorter terms. Their terms are tied to the elections for the House of Representatives, which happen about every three years.

Political Parties in the Senate

Political parties are very important in the Senate. Most senators belong to a party and usually vote together with their party members. Because of the proportional voting system, the Senate often includes members from several different parties.

Often, neither the government nor the main opposition party has over half the seats. This means smaller parties and independent senators can hold the "balance of power." They can decide whether a government's bill will pass or fail, which gives them a lot of influence.

A Day in the Life of the Senate

The Senate has a busy schedule for debating laws and checking the work of the government.

How a Bill Becomes a Law

For a proposed law, called a bill, to pass, it must be approved by both the Senate and the House of Representatives. Here is how a bill usually moves through the Senate:

- First Reading: The bill is formally introduced to the senators.

- Second Reading: Senators debate the main purpose and ideas of the bill.

- Committee Stage: The bill is examined in detail, and senators can suggest changes. Sometimes, a bill is sent to a Senate committee for a deeper investigation.

- Third Reading: After all details are agreed upon, senators take a final vote on the bill.

If the Senate passes the bill, it is sent to the Governor-General to be signed into law.

Senate Committees

Much of the Senate's important work happens in committees. These are small groups of senators from different parties who study specific subjects. They can investigate government actions, examine new bills, and hold public hearings where they can ask questions of experts and government officials.

Committees help the Senate make sure the government is accountable and that laws are well-designed.

Voting in the Chamber

When it is time to vote on a bill, bells are rung throughout Parliament House for four minutes to call senators to the chamber. This vote is called a division.

The doors are locked, and senators move to different sides of the room to show if they vote "Aye" (yes) or "No". The votes are then counted. Because there is an even number of senators (76), a tied vote can happen. If the vote is tied, the proposal is defeated.

What Happens When the Houses Disagree?

Sometimes, the Senate and the House of Representatives cannot agree on a bill.

Double Dissolution

If the Senate rejects a bill from the House of Representatives twice, the Constitution provides a way to break the deadlock. The Prime Minister can ask the Governor-General to call a double dissolution.

This is a special election where every single seat in both the Senate and the House of Representatives is up for election. After the election, the new parliament can vote on the bill again. If they still disagree, they can hold a joint sitting, where both houses meet and vote together. This has only happened once, in 1974.

Blocking Supply

The Senate has the power to reject the government's budget, which is also known as "blocking supply." This is very serious because the government needs this money to run the country.

This happened during the 1975 constitutional crisis. The Senate refused to pass the government's budget, leading to a major political standoff. The crisis ended when the Governor-General, Sir John Kerr, dismissed the Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, and called an election. This is the only time a Prime Minister has been dismissed in this way.

Current Senate

The most recent federal elections were held in 2022 and 2025.

2022 Election

In the 2022 half-Senate election, 40 seats were up for election. The results changed the makeup of the Senate, with the Greens and other smaller parties gaining more seats.

After the election, the composition was:

- Liberal/National Coalition: 32 seats

- Labor: 26 seats

- Greens: 12 seats

- Jacqui Lambie Network: 2 seats

- One Nation: 2 seats

- United Australia: 1 seat

- Independent (David Pocock): 1 seat

2025 Election

In the 2025 half-Senate election, another 40 seats were contested. The Labor party gained seats, while the Coalition lost some.

Following the election, the composition of the Senate was:

- Labor: 29 seats

- Liberal/National Coalition: 27 seats

- Greens: 10 seats

- One Nation: 4 seats

- United Australia: 1 seat

- Jacqui Lambie Network: 1 seat

- Australia's Voice: 1 seat

- Independent: 3 seats

The table below shows the current party representation for each state and territory.

| State | Seats held | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | ||||||||||||

| Victoria | ||||||||||||

| Queensland | ||||||||||||

| Western Australia | ||||||||||||

| South Australia | ||||||||||||

| Tasmania | ||||||||||||

| Australian Capital Territory | ||||||||||||

| Northern Territory | ||||||||||||

See also

In Spanish: Senado de Australia para niños

In Spanish: Senado de Australia para niños

- 2019 Australian federal election

- Canberra Press Gallery

- Clerk of the Australian Senate

- Double dissolution

- Father of the Australian Senate

- List of Australian Senate appointments

- Members of the Australian Parliament who have served for at least 30 years

- Members of the Australian Senate, 2022–2025

- Women in the Australian Senate