Māori history facts for kids

The history of the Māori people tells the story of how the first people arrived in New Zealand, which they called Aotearoa. These early settlers were Polynesian explorers. They traveled across the ocean in large canoes, arriving in New Zealand from the late 1200s or early 1300s. Living far away from other lands, these Polynesian settlers slowly created their own unique Māori culture.

Early Māori history is often split into two main times: the Archaic period (around 1280 to 1500) and the Classic period (around 1500 to 1769). Places like Wairau Bar show us how these early Polynesian communities lived. Many plants they brought from their homeland didn't grow well in New Zealand's colder weather. However, they hunted many native birds and sea animals for food. As the population grew, and there was more competition for food and land, Māori culture changed. This led to the Classic period, where more detailed art developed, and a new warrior culture emerged. People started building strong, fortified villages called Pā. One group of Māori traveled to the Chatham Islands around 1500. They developed a different, peaceful culture and became known as the Moriori people.

When Europeans arrived in New Zealand, starting with Abel Tasman in 1642, big changes came for the Māori. They learned about Western food, tools, weapons, and culture, especially from British settlers. In 1840, the British Crown and many Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi. This agreement made New Zealand part of the British Empire and gave Māori the rights of British citizens. At first, Māori and Europeans (whom Māori called "Pākehā") got along well. But disagreements over land sales led to conflicts in the 1860s. This resulted in large amounts of Māori land being taken. New diseases brought by Europeans also greatly harmed the Māori people. Their population dropped, and their place in New Zealand society became less strong.

However, by the early 1900s, the Māori population began to grow again. People started working to improve their social, political, cultural, and economic standing in New Zealand. A protest movement grew in the 1960s. It sought to fix past wrongs related to the Treaty. In 2013, about 600,000 people in New Zealand identified as Māori. This was about 15 percent of the country's total population.

Contents

Where the Māori Came From: Polynesia

Scientists use clues from genetics, old tools, languages, and human bones to understand where Polynesian people came from. It seems their ancestors came from Taiwan. Studies of how languages changed and DNA evidence suggest that most Pacific people came from Taiwanese groups about 5,200 years ago. These Austronesian ancestors moved south to the Philippines and lived there for some time.

From the Philippines, some sailed southeast. They traveled along the northern and eastern edges of Melanesia, past the coasts of Papua New Guinea and the Bismarck Islands, to the Solomon Islands. They settled there, leaving behind pieces of their Lapita pottery. They also mixed a little with local Melanesian people. From the Solomons, some moved to the western Polynesian islands of Samoa and Tonga. Others continued island-hopping eastward, all the way from Otong Java in the Solomons to the Society Islands of Tahiti and Ra'iatea. From there, many groups of migrants settled the rest of eastern Polynesia. They reached Hawai'i in the north, the Marquesas Islands and Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the east, and finally, New Zealand in the far south.

Studies show that most of the Māori-Polynesian genetic makeup (79 percent) comes from East Asia. Only a smaller part (21 percent) is from Melanesia. This suggests that Polynesians moved through Melanesia quite quickly. They didn't mix much with Melanesian people.

Settling in New Zealand

Scientists have not found any human remains, tools, or buildings in New Zealand that are definitely older than the Kaharoa Tephra. This is a layer of ash from a volcanic eruption of Mount Tarawera around 1314 CE. Some early dates for Polynesian rat bones were found to be wrong. Newer tests on rat bones and other items show dates after the Tarawera eruption.

Pollen evidence shows large forest fires happened a decade or two before the eruption. Some scientists think humans might have started these fires. If so, the first settlers could have arrived between 1280 and 1320 CE. However, the most recent studies suggest that the main settlement happened in the decades after the eruption, between 1320 and 1350 CE. This might have been a planned mass migration. This idea also fits with traditional Māori family histories (called whakapapa). These histories suggest that many of the founding canoes (waka) arrived around 1350 AD. Many Māori today can trace their family lines back to these canoes.

Māori oral stories describe their ancestors arriving in large ocean-going waka from Hawaiki. Hawaiki is seen as a spiritual homeland for many eastern Polynesian groups. Some researchers believe it is a real place: the important island of Raiatea in the Leeward Society Islands (in French Polynesia). In the local language, this island was called Havai'i. The stories of migration are different among various iwi (tribes). Members of an iwi might identify with several waka in their family histories.

The settlers brought several useful species with them that grew well. These included the kūmara, taro, yams, gourd, and tī. They also brought aute (paper mulberry), as well as dogs and rats. Other species from their homeland likely came too but did not survive the journey or thrive in New Zealand.

In recent decades, DNA research has helped estimate the number of women in the first group of settlers. It is thought to be between 50 and 100 women. A 2022 study using radiocarbon dating from over 500 old sites suggests that early Māori settlement in the North Island happened between 1250 and 1275 AD. This is similar to a 2010 study that pointed to 1280 as an arrival time.

The Archaic Period (around 1280–1500)

The earliest time of Māori settlement is called the "Archaic" or "Moahunter" period. The eastern Polynesian ancestors of the Māori arrived in a land covered in forests. It had many birds, including several types of moa that are now extinct. These moa birds weighed from 20 kg to 250 kg. Other extinct birds included the New Zealand swan and the New Zealand goose. The giant Haast's eagle, which hunted moa, also lived then. Sea animals, especially seals, were common along the coasts. There is evidence of seal colonies much further north than where they are found today. Huge numbers of moa bones have been found near the Waitaki River on the South Island's east coast. At the mouth of the Shag River, it seems that humans killed at least 6,000 moa in a short time.

Old sites show that the Otago region was a key place for Māori culture during this period. Most early settlements were on or near the coast. People often set up small, temporary camps inland for seasonal hunting. Settlements varied in size. Some had about 40 people, while others, like at Shag River, had 300 to 400 people and forty buildings.

The most famous Archaic site is Wairau Bar in the South Island. This site is like the early Polynesian villages. It is the only place in New Zealand where bones of people born elsewhere have been found. Dating methods show a wide range of dates for this site, from the early 1200s to the early 1400s. Studies of skeletons from Wairau Bar in 2010 showed that people did not live very long. The oldest skeleton was 39, and most people died in their 20s. Most adults showed signs of not getting enough food or having infections. Anaemia (low iron) and arthritis were common. Some skeletons showed signs of diseases like tuberculosis. On average, the adults were taller than other South Pacific people. Men were about 170 cm (5 ft 7 in) tall, and women were about 160 cm (5 ft 3 in) tall.

The Archaic period is special because there were no weapons or forts, which were common later. It also had unique "reel necklaces." During and after this period, about 32 bird species became extinct. This happened because of too much hunting by humans and the rats and dogs they brought. Also, repeated burning of plants changed their homes, and the climate became cooler from about 1400–1450. For a short time, less than 200 years, early Māori ate many large birds and fur seals that had never been hunted before. These animals quickly disappeared. Many, like the moa, New Zealand swan, and kohatu shag, became extinct. Others, like kākāpō and seals, became fewer in number and lived in smaller areas.

Research shows that Māori used about 36 different food plants. Many of these needed special preparation to remove poisons and long cooking times (12–24 hours). Studies on early Māori families found that women had their first child around age 20. The average number of births was low compared to other early farming societies. This might have been because people lived for a very short time, about 31–32 years on average. Skeletons from Wairau Bar showed signs of a hard life, with many having healed broken bones. This suggests that people ate well and had a supportive community that could help injured family members.

The Classic Period (1500–1768)

A study of tree rings near Hokitika shows that the climate became much colder from 1500. This was a sudden and long-lasting cooler period. At the same time, there were big earthquakes in the South Island and a major earthquake in the Wellington area in 1460. Tsunamis also destroyed many coastal settlements. The moa and other food animals became extinct. These events likely caused big changes in Māori culture, leading to the "Classic" period. This was the culture that Europeans found when they first arrived.

This period is known for beautiful weapons and ornaments made from pounamu (greenstone). Canoes were carved with detailed designs. This carving tradition later grew to include elaborately carved meeting houses called wharenui. A strong warrior culture also developed. Māori built strong hillforts known as pā. They also made some of the largest war canoes (waka taua) ever built.

Around the year 1500, a group of Māori moved east to Rēkohu, now called the Chatham Islands. There, they adapted to the local climate and available resources. They developed into a people known as the Moriori, who were related to but different from the Māori of mainland New Zealand. A key part of Moriori culture was their focus on pacifism (being peaceful). When a group of invading Māori from Taranaki arrived in 1835, few of the estimated 2,000 Moriori survived. Many were killed, and others were enslaved.

Early European Contact (1769–1840)

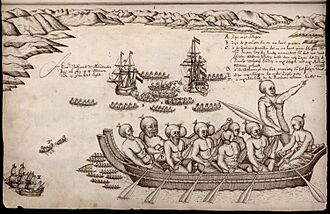

The New Zealand historian, Michael King, said the Māori were "the last major human community on earth untouched and unaffected by the wider world." Besides a short fight at sea with Abel Tasman in 1642, the first real contact with the outside world happened with Captain Cook's group in 1769. He had more contact in 1773 and 1777. Cook spent time mapping the islands in 1769 and meeting Māori, especially in the Marlborough Sounds in 1777. Cook and his crew wrote down what they thought of the Māori at that time. This early contact was sometimes difficult and even deadly.

From the 1780s, Māori met European and American sealers and whalers. Some Māori worked as crew on these foreign ships, especially on whaling and sealing ships in New Zealand waters. Some crews in the South Island were almost all Māori. Between 1800 and 1820, there were many sealing and whaling trips to New Zealand, mostly from Britain and Australia. A few escaped prisoners from Australia and sailors who left their ships, as well as early Christian missionaries, also brought outside influences. During the Boyd Massacre in 1809, Māori took hostage and killed 66 people from the ship Boyd. This was likely revenge for the captain whipping the son of a Māori chief. Because of this attack, shipping companies and missionaries stayed away for several years.

Some Europeans who ran away from ships or prisons lived among Māori. They were called Pākehā Māori. Many Māori valued them because they could share European knowledge and technology, especially firearms. When Whiria (Pōmare II) led a war party in 1838, he had 131 Europeans among his fighters. European settlement in New Zealand grew steadily. By 1839, about 2,000 Europeans lived among Māori, mostly in the North Island.

Between 1805 and 1840, Māori tribes started getting muskets from European visitors. This led to a desperate need for muskets to avoid being defeated by their neighbors. The new introduction of the potato also allowed Māori tribes to go on longer war campaigns. This time was known as the Musket Wars, a period of very bloody fighting between tribes. Many groups were greatly reduced in number, and others were forced to leave their traditional lands. The great need for trade goods, mostly New Zealand flax, led many Māori to move to unhealthy swampy areas where flax could grow. It is thought that during this time, the Māori population dropped from about 100,000 (in 1800) to between 50,000 and 80,000 by 1843. The peaceful Moriori people in the Chatham Islands also suffered greatly. They were attacked and enslaved by some Ngāti Mutunga and Ngāti Tama Māori who had fled from the Taranaki region.

At the same time, Māori suffered many deaths from European diseases like influenza, smallpox, and measles. These diseases killed an unknown number of Māori, possibly between 10 and 50 percent. The diseases spread quickly because Māori had no natural protection against them. The 1850s were a time of peace and economic growth for Māori. But a large number of European settlers arrived in the 1870s, increasing contact between Māori and newcomers.

Te Rangi Hīroa wrote about an epidemic of a breathing illness Māori called rewharewha. It "wiped out" populations in the early 1800s. He said it "spread with amazing speed throughout the North Island and even to the South." He also noted that "Measles, typhoid, scarlet fever, whooping cough and almost everything, except plague and sleeping sickness, have taken their toll of Maori dead."

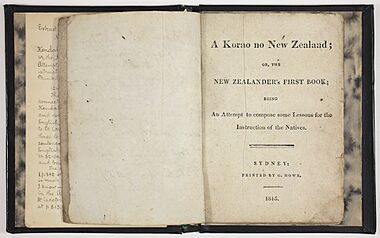

Contact with Europeans led to a sharing of ideas. The Māori language was first written down by Thomas Kendall in 1815 in his book A korao no New Zealand. Five years later, a grammar and vocabulary book was made by Professor Samuel Lee. He was helped by Kendall and the chiefs Hongi Hika and Waikato when they visited England in 1820. Māori quickly started using writing to share their ideas. Many of their oral stories and poems were written down. Between 1835 and 1840, William Colenso printed 74,000 Māori-language booklets. In 1843, the government gave free newspapers to Māori called Ko Te Karere O Nui Tireni. These had information about laws and crimes, and explained European customs. They were meant to share official information and encourage the idea that Pākehā and Māori were united by the Treaty of Waitangi.

The Treaty of Waitangi (1840)

Before 1840, New Zealand was not officially part of the British Empire. This meant it was outside British law. In 1839, stories of growing lawlessness and uncontrolled land buying by British people reached London. The British government decided to act. On May 6, 1839, they expanded the New South Wales colony to include New Zealand. They sent Royal Navy captain, William Hobson, with orders to take control of New Zealand after talking with Māori, and to set up a colony. On February 6, 1840, Hobson signed the Treaty of Waitangi with many North Island chiefs at Waitangi. Most other chiefs around New Zealand signed the treaty during 1840. Some chiefs refused to sign. In May 1840, Hobson declared British control. First, over the North Island based on Māori giving up some power. Second, over the South Island, because it was seen as empty land. Hobson then became the colony's first governor.

The Treaty gave Māori the rights of British citizens. It also promised to protect Māori property rights and tribal independence. In return, Māori accepted British sovereignty (rule). There are still many disagreements about parts of the Treaty of Waitangi. The original treaty was mostly written by James Busby. It was translated into Māori by Henry Williams, who knew Māori fairly well, and his son William, who was more skilled. At Waitangi, the chiefs signed the Māori translation.

Land Disputes and Conflicts

Even with different understandings of the Treaty of Waitangi, relations between Māori and Europeans were mostly peaceful in the early colonial period. Many Māori groups started successful businesses. They supplied food and other products for New Zealand and for selling overseas. Some early European settlers learned the Māori language and wrote down Māori mythology. This included George Grey, who was Governor of New Zealand from 1845 to 1855 and again from 1861 to 1868.

However, growing tensions over disputed land sales led to the New Zealand wars in the 1860s. Also, Māori in the Waikato region tried to create their own system of leadership, called the Māori King Movement (Kīngitanga). Some saw this as a challenge to British rule. These conflicts began when some Māori attacked settlers in Taranaki. But the main fighting was between Crown troops (from Britain and Australia, helped by settlers and some allied Māori called kupapa) and many Māori groups who opposed the land sales. This included some Waikato Māori.

These conflicts did not cause as many Māori or European deaths as the earlier Musket Wars. However, the colonial government took large areas of tribal land. This was punishment for what they called rebellions. In some cases, land was taken from tribes that had not fought in the war, though this land was often returned quickly. Some confiscated land was given back to both allied Māori and "rebel" Māori. A few smaller conflicts also happened after the main wars, like the event at Parihaka in 1881.

The Native Land Acts of 1862 and 1865 created the Native Land Court. This court was meant to change Māori land from being owned by the whole community to being owned by individual families. The goal was to help Māori fit into European society and make it easier for Europeans to buy land. Māori land owned by individuals could then be sold to the government or to settlers. Between 1840 and 1890, Māori sold 95 percent of their land. Only 4 percent of this was confiscated land, and about a quarter of that was returned. Some Māori leaders received a lot of money from these land sales. Later, some argued that selling off Māori land and not having the right skills made it hard for Māori to take part in New Zealand's economy. This eventually made it difficult for many Māori to support themselves.

The Māori MP Henare Kaihau worked with King Mahuta to sell land to the government. At that time, the King sold 185,000 acres each year. In 1910, a Māori Land Conference discussed selling another 600,000 acres. King Mahuta had managed to get some previously taken land back. Henare Kaihau invested all the money, 50,000 pounds, in a company that failed, and all the Kīngitanga money was lost.

In 1884, King Tāwhiao took money from the Kīngitanga bank to travel to London. He wanted to meet Queen Victoria and ask her to honor the Treaty. But he could not get past the Secretary of State for the Colonies, who said it was a New Zealand problem.

By 1891, Māori made up only 10 percent of the population. But they still owned 17 percent of the land, though much of it was not good quality.

Decline and Revival

By the late 1800s, many Pākehā and Māori believed that the Māori people would disappear as a separate group. They thought Māori would become part of the European population. In 1840, New Zealand had about 50,000 to 70,000 Māori and only about 2,000 Europeans. By 1860, the number of Europeans grew to 50,000. The Māori population dropped to 37,520 in the 1871 census. By the 1896 census, it was 42,113, while Europeans numbered over 700,000. Professor Ian Pool noted that as late as 1890, 40 percent of all Māori baby girls died before their first birthday. This was a much higher rate than for boys.

However, the decline of the Māori population stopped, and it began to grow again. By 1936, the Māori population was 82,326. Even though there was a lot of mixing between Māori and European people, many ethnic Māori kept their cultural identity. People started discussing what it meant to be "Māori."

In 1867, the parliament created four Māori seats. This gave all Māori men the right to vote, 12 years before European New Zealand men. New Zealand was the first country settled by Europeans to give its native people the right to vote. While the Māori seats encouraged Māori to take part in politics, the Māori population at the time would have needed about 15 seats to be fairly represented.

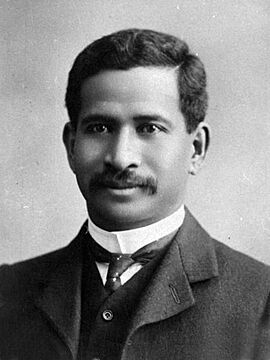

From the late 1800s, successful Māori politicians like James Carroll, Āpirana Ngata, Te Rangi Hīroa, and Maui Pomare became important in politics. At one point, Carroll even became Acting Prime Minister. This group, known as the Young Māori Party, worked to bring back the strength of the Māori people after the hard times of the past century. They believed that the future involved some mixing with European ways. They thought Māori should adopt European practices like Western medicine and education, especially learning English.

During the First World War, a Māori pioneer force was sent to Egypt. It quickly became a successful fighting infantry battalion. In the last years of the war, it was called the "Māori Pioneer Battalion." It was mostly made up of people from Te Arawa, Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki, Te Aitanga-a-Hauiti, Ngāti Porou, and Ngāti Kahungunu tribes, and later many Cook Islanders. The Waikato and Taranaki tribes refused to join or be forced into service.

Māori were greatly affected by the 1918 influenza epidemic when the Māori battalion returned from the war. The death rate from influenza for Māori was 4.5 times higher than for Pākehā. Many Māori, especially in the Waikato, did not want to see a doctor. They only went to a hospital when they were very sick. To cope with being isolated, Waikato Māori, led by Te Puea, increasingly returned to the old Pai Mārire (Hau hau) beliefs from the 1860s.

Until 1893, 53 years after the Treaty of Waitangi, Māori did not pay tax on their land. In 1893, a very small tax was only paid on leased land. It was not until 1917 that Māori had to pay a heavier tax, which was half of what other New Zealanders paid.

During the Second World War, the government decided to excuse Māori from the forced military service that applied to other citizens. Māori volunteered in large numbers, forming the 28th or Māori Battalion. In total, 16,000 Māori took part in the war. Māori, including Cook Islanders, made up 12 percent of the total New Zealand force. 3,600 served in the Māori Battalion. The rest served in other parts of the military, like artillery, pioneers, home guard, infantry, air force, and navy.

Recent History (1960s–Present)

Since the 1960s, Māori culture has seen a strong revival. At the same time, there has been activism for fairness and a protest movement. The government has recognized the growing political power of Māori. This has led to some compensation for land that was taken and for other rights that were broken. In 1975, the government set up the Waitangi Tribunal. This group investigates and makes suggestions on these issues. However, it cannot make final decisions, and the Government does not have to accept its findings. Since 1976, people of Māori descent can choose to vote in either the general elections or the Māori elections. They can vote in either Māori or general electorates, but not both.

During the 1990s and 2000s, the government talked with Māori to provide compensation for times when the Crown broke the promises in the Treaty of Waitangi. By 2006, the government had given over NZ$900 million in settlements, much of it as land deals. The largest settlement, signed in 2008 with seven Māori iwi, gave nine large areas of forest land to Māori control. Because of these payments to many iwi, Māori now have important interests in the fishing and forestry industries. A growing number of Māori leaders are using these treaty settlements to invest in economic development.

|

See also

- Pre-Māori settlement of New Zealand theories

- Māori mythology

- History of New Zealand

- History of Oceania

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |