Pertussis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Whooping cough |

|

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Pertussis, 100-day cough |

| Symptoms | Runny nose, fever, cough |

| Complications | Vomiting, broken ribs, exhaustion |

| Duration | ~ 10 weeks |

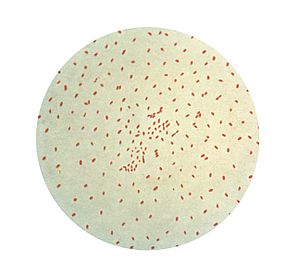

| Causes | Bordetella pertussis (spread through the air) |

| Diagnostic method | Nasopharyngeal swab |

| Prevention | Pertussis vaccine |

| Treatment | Antibiotics (if started early) |

| Frequency | 16.3 million (2015) |

| Deaths | 58,700 (2015) |

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis or the 100-day cough, is a very contagious sickness caused by bacteria. It can be prevented with a vaccine. At first, it feels like a common cold with a runny nose, fever, and a mild cough. But then, it turns into severe coughing fits that can last for two or three months.

After a coughing fit, a person might make a high-pitched "whoop" sound or gasp when they breathe in. This strong coughing can last for 10 weeks or more, which is why it's called the "100-day cough." Sometimes, people cough so hard they might vomit, break a rib, or become very tired. Babies under one year old might not cough much at all. Instead, they might have times when they stop breathing. It usually takes about 7 to 10 days to show symptoms after getting infected. People who have been vaccinated can still get whooping cough, but their symptoms are usually much milder.

Whooping cough is caused by a type of bacteria called Bordetella pertussis. It spreads easily when an infected person coughs or sneezes. People can spread the sickness from when their symptoms start until about three weeks into the coughing fits. If they take antibiotics, they stop being contagious after five days. Doctors diagnose whooping cough by taking a sample from the back of the nose and throat. This sample can then be tested to find the bacteria.

The best way to prevent whooping cough is by getting the pertussis vaccine. Babies usually get their first shot between six and eight weeks old, with four doses given in their first two years. The protection from the vaccine lessens over time, so older kids and adults often need more doses. Getting vaccinated during pregnancy is very good at protecting the baby during their first few months of life, when they are most vulnerable. If someone has been exposed to whooping cough and is at risk of getting very sick, antibiotics can sometimes help prevent the disease. For those who already have the sickness, antibiotics work best if started within three weeks of the first symptoms. After that, they don't help much for most people. About half of infected babies under one year old need to go to the hospital, and about 1 in 200 babies die from it.

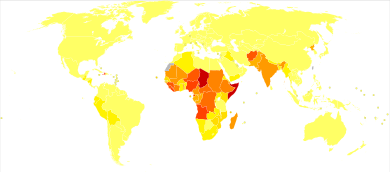

In 2015, about 16.3 million people worldwide got whooping cough. Most cases happen in developing countries. In 2015, whooping cough caused 58,700 deaths. This number was lower than in 1990, when 138,000 people died. Doctors first wrote about whooping cough in the 1500s. The bacteria that causes it was found in 1906, and the vaccine became available in the 1940s.

Contents

What are the signs and symptoms?

The main signs of whooping cough are a strong, uncontrolled cough, a "whoop" sound when breathing in, and sometimes fainting or vomiting after coughing. The severe coughing can cause problems like subconjunctival hemorrhages (burst blood vessels in the eye), rib fractures, and urinary incontinence (losing control of pee). Vomiting after a cough or making a whooping sound makes it much more likely that someone has whooping cough.

The sickness usually starts with mild cold-like symptoms, such as a mild cough, sneezing, or a runny nose. This is called the catarrhal stage. After one or two weeks, the coughing becomes very strong and hard to control. This is often followed by a high-pitched "whoop" sound as the person tries to breathe in. About half of children and adults with whooping cough make this "whoop" sound during this stage, which is called the paroxysmal stage.

This stage usually lasts for two to eight weeks, or sometimes even longer. Then, people slowly start to get better in what's called the convalescent stage, which lasts one to four weeks. During this time, the coughing fits happen less often. However, even months later, a person might have coughing fits again if they get another cold or respiratory infection.

The symptoms of whooping cough can be different, especially between people who have been vaccinated and those who haven't. Vaccinated people often have a milder infection. Their strong cough might only last a couple of weeks, and they might not make the "whooping" sound. Even though vaccinated people have a milder sickness, they can still spread the disease to others who are not immune.

How long does it take to show symptoms?

The time between being exposed to the bacteria and showing symptoms is usually 7 to 14 days. Sometimes, it can be as short as 6 days or as long as 20 days, but rarely up to 42 days.

What causes whooping cough?

Whooping cough is caused by the bacteria Bordetella pertussis. It is an airborne disease, meaning it spreads easily through tiny droplets in the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

How is whooping cough diagnosed?

Checking symptoms

A doctor's overall feeling about a person's symptoms is often the best way to first guess if it's whooping cough. For adults with a cough lasting less than 8 weeks, vomiting after coughing or a "whoop" sound can suggest whooping cough. If there are no strong coughing fits or if there's a fever, it's probably not whooping cough. For children with a cough lasting less than 4 weeks, vomiting after coughing can be a sign, but it's not a definite answer.

Lab tests

To confirm the diagnosis, doctors can take a sample from the nose and throat. This sample can be grown in a lab to find the bacteria, or tested using a method called polymerase chain reaction (PCR). These tests work best during the first three weeks of the illness. After that, it's harder to find the bacteria.

For adults and teenagers who have been sick for several weeks, blood tests can check for high levels of antibodies (special proteins the body makes to fight infection) against the whooping cough bacteria.

Similar illnesses

A milder sickness, similar to whooping cough, can be caused by a different type of bacteria called B. parapertussis.

How can we prevent whooping cough?

The main way to prevent whooping cough is through vaccination. While antibiotics might be used for people who have been exposed but don't have symptoms, there isn't enough proof that they always work. However, preventive antibiotics are often given to those who have been exposed and are at high risk of getting very sick, like babies.

Vaccine

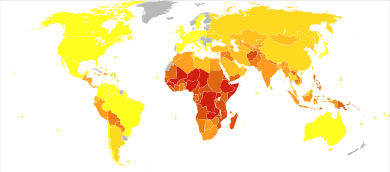

Pertussis vaccines are very good at preventing the illness. The World Health Organization and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend them for everyone. In 2002, the vaccine saved an estimated half a million lives.

The modern pertussis vaccine is about 71–85% effective, and even better at preventing severe cases. However, even with many people vaccinated, whooping cough is still common in Western countries. The increase in whooping cough cases in the 2000s is thought to be because the vaccine's protection wears off over time, and the bacteria itself has changed.

The protection from the vaccine doesn't last forever. A study in 2011 showed that protection might only last three to six years. This period covers childhood, which is when kids are most likely to be exposed and are at the highest risk of serious illness or death from whooping cough.

Because so many people are vaccinated, whooping cough cases have shifted from young children (1-9 years old) to babies, teenagers, and adults. Teenagers and adults can carry the bacteria and spread it to babies who haven't had enough vaccine doses yet.

Even if someone has had whooping cough before, they don't have lifelong protection. Studies suggest that natural immunity (from getting sick) can last from 7 to 20 years. Protection from the vaccine usually lasts 4–12 years. Some studies also suggest that when people choose not to vaccinate their children for non-medical reasons, it can lead to more whooping cough cases.

Some research suggests that while the modern pertussis vaccines are good at preventing the disease, they might not stop people from getting infected or spreading the bacteria. This means vaccinated people could still spread whooping cough, even if they only have mild symptoms or no symptoms at all. Even if the sickness is milder in older people, they can still pass it to others who are not immune, including babies who haven't had all their shots. Often, older people are the first ones to get sick in a family and are the source of infection for children.

How is whooping cough treated?

The antibiotics erythromycin, clarithromycin, or azithromycin are usually recommended for treatment. Newer types of antibiotics are often preferred because they have fewer side effects. Another antibiotic, Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX), can be used for people who are allergic to the first-choice antibiotics or for babies who might have a risk of a stomach problem from other antibiotics.

A good rule is to treat people over 1 year old within 3 weeks of their cough starting. For babies under 1 year old and pregnant women, treatment is recommended within 6 weeks of the cough starting. If whooping cough is diagnosed late, antibiotics won't change how long the illness lasts. However, when used early, antibiotics can make a person stop being contagious sooner, which helps prevent the spread of the disease. Short courses of antibiotics (like azithromycin for 3–5 days) work just as well as longer treatments (like erythromycin for 10–14 days) at getting rid of the bacteria, and they have fewer side effects.

People with whooping cough are most contagious during the first two weeks after their symptoms begin.

Unfortunately, there are no effective treatments for the cough itself. Over-the-counter cough medicines are not recommended and have not been found to help.

What is the outlook for whooping cough?

While most healthy older children and adults fully recover from whooping cough, it can be very serious for newborns. About 0.5% (1 in 200) of babies under one year old in the U.S. who get whooping cough die from it. Babies in their first year are also more likely to have complications like apnea (pauses in breathing), pneumonia, and seizures. This might be because the bacteria can weaken the baby's immune system.

How common is whooping cough?

Around the world, about 16 million people get whooping cough every year. In 2013, it caused about 61,000 deaths, which was a decrease from 138,000 deaths in 1990. Another estimate says 195,000 children die from the disease worldwide each year. This happens even though many people get the DTP and DTaP vaccines. Whooping cough is one of the main causes of deaths that could be prevented by vaccines. About 90% of all cases happen in developing countries.

Before vaccines, the U.S. reported an average of 178,171 cases each year, with peaks every two to five years. More than 93% of these cases were in children under 10. The actual number of cases was probably much higher. After vaccines were introduced in the 1940s, whooping cough cases dropped a lot, to about 1,000 by 1976. However, the number of cases has increased since 1980. In 2015, 20,762 people in the United States were reported to have whooping cough. Whooping cough is the only vaccine-preventable disease in the U.S. that has seen an increase in deaths. The number of deaths went from four in 1996 to 17 in 2001, almost all of which were babies under one year old. In the U.S., whooping cough in adults has increased a lot since about 2004.

In Canada, the number of whooping cough infections has been between 2,000 and 10,000 reported cases each year over the last ten years. It is the most common vaccine-preventable illness in Toronto.

In 2009, Australia reported an average of 10,000 cases a year, and the number of cases had increased.

In 2017, India reported 23,766 whooping cough cases, one of the highest numbers that year. Other countries like Germany reported 16,183 cases, while Australia had 12,114 and China had 10,390 cases.

Outbreaks in the US

In 2010, 10 babies in California died, and health officials said there was an epidemic with 5,978 confirmed cases. They found that doctors had not correctly diagnosed the babies' condition during several visits. Studies showed that communities with many non-medical vaccine exemptions had more cases. The number of exemptions varied a lot, but they tended to be grouped together. In some schools, more than 75% of parents chose not to vaccinate their children. This suggests that refusing vaccines for non-medical reasons made the outbreak worse. Other reasons for the outbreak included the vaccine's protection wearing off and many vaccinated adults and older children not getting a booster shot.

In April and May 2012, whooping cough was declared an epidemic in Washington, with 3,308 cases. In December 2012, Vermont declared an epidemic with 522 cases. Wisconsin had the highest number of cases, with 3,877, though it didn't officially declare an epidemic.

History of whooping cough

Discovery of the bacteria

The bacteria that causes whooping cough, B. pertussis, was discovered in 1906 by Jules Bordet and Octave Gengou. They also created the first tests and vaccine for it. Scientists started working on a vaccine soon after the bacteria was grown in a lab that year. In the 1920s, Louis W. Sauer developed a weak vaccine. In 1925, a Danish doctor named Thorvald Madsen was the first to test a vaccine on many people. He used it to control outbreaks in the Faroe Islands.

Development of the vaccine

In 1932, a whooping cough outbreak hit Atlanta, Georgia. This led pediatrician Leila Denmark to study the disease. Over the next six years, her work was published, and she helped develop the first pertussis vaccine with Emory University and Eli Lilly & Company. In 1942, American scientists Grace Eldering, Loney Gordon, and Pearl Kendrick combined the whooping cough vaccine with diphtheria and tetanus vaccines to create the first DTP combination vaccine. To reduce side effects, a Japanese scientist named Yuji Sato developed a newer, "acellular" vaccine in 1981. This vaccine used only parts of the bacteria. Later versions of this acellular vaccine in other countries were often part of the DTaP combination vaccine.

In Spanish: Tos ferina para niños

In Spanish: Tos ferina para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |