Kākāpō facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Kākāpō |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Celebrity kākāpō Sirocco on Maud Island | |

| Conservation status | |

Nationally Critical (NZ TCS) |

|

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Superfamily: | Strigopoidea |

| Family: | Strigopidae Bonaparte, 1849 |

| Genus: | Strigops G.R. Gray, 1845 |

| Species: |

S. habroptila

|

| Binomial name | |

| Strigops habroptila G.R. Gray, 1845

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Strigops habroptilus |

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The kākāpō (pronounced KAH-kuh-poh) is a very special and rare parrot from New Zealand. Its name comes from the Māori words kākā (parrot) and pō (night), because it is active at night. It's also called the owl parrot because its face looks a bit like an owl's.

This amazing bird is unique in many ways. It's the only flightless parrot in the world, meaning it can't fly. It's also the heaviest parrot, and it's nocturnal, which means it sleeps during the day and is awake at night. Kākāpō are herbivores, eating only plants. They can live for a very long time, possibly up to 100 years!

Sadly, the kākāpō is critically endangered. This means there are very few of them left. All the known kākāpō live on special islands in New Zealand where they are safe from predators. In 2023, some kākāpō were even moved back to mainland New Zealand.

Contents

Understanding the Kākāpō: Its Name and Family

The kākāpō was first officially described in 1845 by an English bird expert named George Robert Gray. He gave it the scientific name Strigops habroptila. The name Strigops means "owl face" in Ancient Greek, and habroptila means "soft feather". This is a perfect description, as kākāpō have very soft feathers and an owl-like face!

The Māori name, kākāpō, is used for both one bird and many birds. It's a very old name that shows how important this bird was to the Māori people.

The kākāpō belongs to a family of parrots called Strigopidae. This family also includes two other parrots found only in New Zealand: the kea and the kākā. Scientists believe these New Zealand parrots separated from other parrots millions of years ago.

What Does a Kākāpō Look Like?

The kākāpō is a big, round parrot. Adults can be about 60 centimeters (2 feet) long. Males are heavier than females, weighing around 2 kilograms (4.4 pounds) on average, while females weigh about 1.5 kilograms (3.3 pounds). This makes the kākāpō the heaviest living parrot species.

Even though it has wings, the kākāpō cannot fly. Its wings are too short for its body size, and it doesn't have the strong breastbone (called a keel) that flying birds need for their flight muscles. Instead, kākāpō use their wings for balance when climbing or to slow their fall if they jump from a tree. They can also store a lot of body fat, which helps them survive when food is scarce.

The kākāpō's feathers are yellowish-green with black or dark brown spots. This special coloring helps them blend in perfectly with the plants around them, making them hard to see. Their feathers are also incredibly soft, which is why their scientific name includes "soft feather."

They have a clear, owl-like face with fine feathers that form a disc. Around their beak, they have delicate feathers that look like whiskers. These might help them feel the ground as they walk with their heads down. Kākāpō have dark brown eyes and a large, grey beak. Their feet are big and scaly, with two toes pointing forward and two pointing backward, which is great for climbing. Their tail feathers often get worn down because they drag on the ground.

You can tell female kākāpō apart from males because females have a narrower head, a longer beak, and more slender, pinkish-grey legs. Their feathers are also a bit less yellow and mottled.

Young kākāpō chicks are covered in greyish-white fluff, and you can see their pink skin underneath. As they grow, their feathers become a duller green.

Kākāpō Senses and Smell

Kākāpō have a very good sense of smell, which is important for them since they are active at night. They can sniff out different foods while looking for them.

One of the most interesting things about the kākāpō is its unique, sweet, musty smell. This smell is so strong that it can sometimes alert predators to the kākāpō's presence.

Because they are nocturnal, kākāpō have special eyes that help them see in the dark. They are very good at seeing in low light, but their vision isn't as sharp as birds that hunt during the day.

Kākāpō Genetics

Because there were so few kākāpō left at one point (only 49 birds!), they have very little genetic diversity. This means they are all very similar genetically, which can make them more likely to get sick or have trouble reproducing. Scientists are working to map the genes of all living kākāpō to help with conservation efforts.

Where Kākāpō Live

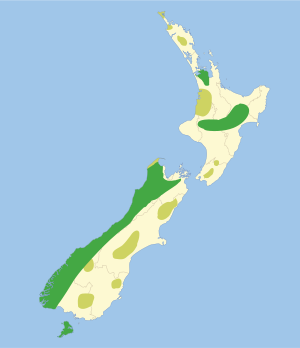

Before humans arrived in New Zealand, kākāpō lived all over the main islands. They could be found in many different places, like grasslands, bushy areas, and forests. They were very adaptable and could live in hot, dry summers or cold, sub-alpine winters. Today, they only live on special islands that are free of predators.

Kākāpō Habits and Lifestyle

Kākāpō are mostly active at night. During the day, they rest hidden under trees or on the ground. At night, they move around their territory.

Even though they can't fly, kākāpō are excellent climbers. They can climb to the very tops of tall trees. They can also "parachute" down by jumping and spreading their wings, which helps them glide a short distance. Because they don't fly, they don't need a lot of energy, so they can survive on small amounts of food or low-quality food.

Kākāpō are completely herbivorous, meaning they only eat plants. They munch on fruits, seeds, leaves, stems, and roots. When they eat, they often leave behind crescent-shaped bits of chewed-up plant fiber, which are a clear sign that a kākāpō has been there.

They have strong legs and can move quickly with a "jog-like" walk. A female kākāpō might walk up to 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) each night to find food for her chicks. Males can walk even further, up to 5 kilometers (3 miles), during mating season.

Kākāpō are naturally curious and sometimes interact with people. Conservation workers who care for them say that each kākāpō has its own unique personality.

Before humans arrived, kākāpō were very good at avoiding their natural predators, which were birds of prey like the New Zealand falcon and the huge Haast's eagle. To stay safe, kākāpō developed their camouflage and became nocturnal, as these birds hunted during the day. When a kākāpō feels threatened, it freezes, blending in with its surroundings.

However, these defenses didn't work against the new predators that humans brought to New Zealand, like cats, rats, and stoats. These mammals hunt differently, often at night, and rely on their sense of smell and hearing, which the kākāpō's strong scent made it vulnerable to.

Kākāpō Reproduction and Life Cycle

The kākāpō has a very unusual way of breeding. It's the only flightless bird in the world that uses a "lek" breeding system. This means that male kākāpō gather in a special area and compete to attract females. Females come to listen to the males' calls and choose a mate.

During the mating season, males go to hilltops and ridges to set up their mating courts. These areas can be far from their usual homes. Males will sometimes fight to get the best spots.

Kākāpō don't breed every year. They only breed when certain trees, especially the rimu tree, produce a lot of fruit. This happens only every three to five years, providing plenty of food for the chicks. In these breeding years, males will make loud, deep "booming" calls for many hours every night, for several months.

Each male digs one or more bowl-shaped hollows in the ground. These "bowls" are about 10 centimeters (4 inches) deep and are often next to rocks or tree trunks, which helps the sound of their booms travel further. The males keep these bowls and the paths connecting them very clean.

The booming calls can be heard at least 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) away. Females are attracted by these calls and will walk long distances to find a male. After mating, the female goes back to her own territory to lay eggs and raise her chicks. The male continues booming to attract other females.

Female kākāpō lay 1 to 4 eggs per breeding season. The nest is usually on the ground, hidden under plants or in hollow logs. The female sits on the eggs, but she has to leave the nest every night to find food. This can be risky for the eggs, as they might get cold or be eaten by predators. Kākāpō eggs usually hatch in about 30 days. The chicks are born fluffy and grey, but they are very helpless. The mother feeds them for about three months, and they stay with her for some time after they leave the nest.

Kākāpō live a long time, usually around 60 years. Males start booming and trying to attract mates when they are about 5 years old. Females can start reproducing around 5 to 9 years old. Because they don't breed every year and have few chicks, kākāpō have one of the slowest reproduction rates among birds.

Scientists have also found that female kākāpō can change the number of male or female chicks they have, depending on how much food is available. If there's plenty of food, they tend to have more male chicks. This helps the species survive.

What Kākāpō Eat

The kākāpō's beak is specially made for grinding food into very fine pieces. They are completely herbivorous, eating native plants, seeds, fruits, pollen, and even the soft inner wood of trees. They especially love the fruit of the rimu tree and will eat only that when it's plentiful.

When a kākāpō eats, it strips out the good parts of the plant and leaves behind a ball of indigestible fiber. These little clumps of fiber are a clear sign that a kākāpō has been in the area. Scientists believe kākāpō use special bacteria in their stomachs to help them digest tough plant material.

Their diet changes with the seasons, depending on what plants are available. They might eat different parts of the same plant species at different times.

Kākāpō Conservation Efforts

Fossil records show that kākāpō were once very common in New Zealand before humans arrived. However, their numbers have dropped dramatically since people settled the country. Today, they are considered "Nationally Critical" by New Zealand's Department of Conservation. Efforts to save them began in the 1890s, with the most successful being the Kākāpō Recovery Programme, which started in 1995.

Kākāpō are fully protected by New Zealand law. It's also illegal to trade them internationally.

How Humans Affected Kākāpō Numbers

The first reason for the kākāpō's decline was the arrival of humans. Māori people hunted kākāpō for food, and used their skins and feathers to make warm cloaks. Because kākāpō can't fly, have a strong scent, and freeze when scared, they were easy prey for Māori hunters and their dogs. The Polynesian rat, which Māori brought with them, also ate kākāpō eggs and chicks. Māori also cleared some forests, reducing the kākāpō's habitat.

When European settlers arrived, kākāpō numbers dropped even faster. Settlers cleared huge areas of land for farms, destroying more kākāpō habitat. They also brought more new predators, like domestic cats, black rats, and stoats.

In the 1880s, many stoats, ferrets, and weasels were released in New Zealand to control rabbits. But these animals also hunted native species, including the kākāpō. Other animals, like introduced deer, ate the same plants as kākāpō, making it harder for the birds to find food. By the 1920s, kākāpō were gone from the North Island and rapidly disappearing from the South Island.

Early Efforts to Save the Kākāpō

In 1891, the New Zealand government made Resolution Island a nature reserve. A caretaker named Richard Henry began moving kākāpō and kiwi from the mainland to this predator-free island. He moved over 200 kākāpō in six years. However, by 1900, stoats had swum to Resolution Island and wiped out the kākāpō population there.

Other attempts to move kākāpō to different islands also failed because of predators like feral cats. By the 1970s, scientists weren't even sure if the kākāpō still existed.

Then, in 1977, kākāpō were found on Stewart Island / Rakiura. This was exciting news, as the population was estimated to be 100 to 200 birds, and it included females! However, feral cats on Stewart Island were killing kākāpō very quickly. To save the birds, scientists decided to move them to islands that were completely free of predators. This big move happened between 1982 and 1997.

The Kākāpō Recovery Programme

In 1995, the Kākāpō Recovery Programme was officially started by the New Zealand Department of Conservation.

The main goal was to move all remaining kākāpō to safe islands where they could breed without predators. Four islands were chosen: Maud, Little Barrier, Codfish, and Mana. Sixty-five kākāpō were successfully moved to these islands. Some islands had to be cleared of predators multiple times. Eventually, Little Barrier and Mana islands were found to be unsuitable, and new sanctuaries were chosen: Chalky Island and Anchor Island.

Extra Food for Kākāpō

A very important part of the Recovery Programme is giving extra food to female kākāpō. Since kākāpō only breed every few years when certain trees produce a lot of fruit, providing extra food helps make sure the females are healthy enough to lay eggs and raise chicks. This extra food also helps increase the number of female chicks born, which is important for growing the population. Today, special parrot food is given to all breeding-age kākāpō on Whenua Hou and Anchor Island. Their weight and how much they eat are carefully watched.

Taking Care of Nests

Kākāpō nests are closely managed by conservation staff. Even though the islands are now predator-free, infrared cameras are used to watch the mothers and chicks. This helps rangers know when to check on the chicks' health. If a mother kākāpō has too many chicks or if some chicks are not growing well, rangers might move them to another nest or even hand-raise them. In 2019, eggs were even removed from nests to encourage females to lay more eggs, leading to a record number of 80 chicks!

Monitoring Every Bird

To keep track of every kākāpō, each bird (except very young chicks) has a radio transmitter. Every known kākāpō has a name, and detailed information is collected about each one. GPS transmitters are also being tested to learn more about where the birds move and how they use their habitat. These signals also tell rangers about mating and nesting, even from far away.

Bringing Kākāpō Back

The Kākāpō Recovery Programme has been very successful, and the number of kākāpō is slowly but steadily growing. The main goal is to create at least one healthy, self-sustaining population of kākāpō that doesn't need constant human help. Resolution Island is being prepared for kākāpō to be reintroduced there. In July 2023, four male kākāpō were moved to Maungatautari on mainland New Zealand, marking the first time kākāpō have lived on the mainland in a very long time.

Fungal Infection Outbreak

In 2019, a fungal disease called aspergillosis affected kākāpō on Whenua Hou island. It infected 21 birds and caused 9 deaths. Over 50 birds had to be taken to veterinary centers for treatment.

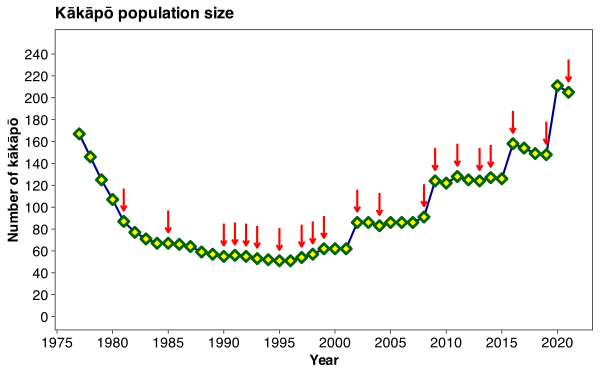

Kākāpō Population Over Time

- 1977: Kākāpō were rediscovered on Stewart Island / Rakiura.

- 1989: Most kākāpō were moved from Rakiura to Whenua Hou and Hauturu-O-Toi (Little Barrier Island).

- 1995: The kākāpō population was only 51 birds; the Kākāpō Recovery Programme began.

- 1999: Kākāpō were removed from Hauturu.

- 2002: A good breeding season resulted in 24 chicks.

- 2005: The population reached 41 females and 45 males; kākāpō were moved to Anchor Island.

- 2009: The total kākāpō population went over 100 for the first time since monitoring began.

- December 2010: "Richard Henry", possibly the oldest known kākāpō (around 80 years old), died.

- 2012: Seven kākāpō were moved back to Hauturu to try and start a breeding program there again.

- 2016: First breeding on Anchor Island; a significant breeding season with 32 chicks. The population grew to over 150.

- 2019: The best breeding season on record! Over 200 eggs were laid, and 72 chicks survived. The population reached 200 birds (juvenile or older) by August 17, 2019.

- 2022: The population increased to 252 birds after another successful breeding season.

- 2023: Kākāpō were reintroduced to mainland New Zealand for the first time in many years.

Kākāpō in Māori Culture

The kākāpō has a rich history in Māori stories and beliefs. Māori believed the kākāpō could predict the future because its breeding cycle was linked to when certain trees produced a lot of fruit.

Kākāpō for Food and Clothing

Māori people considered kākāpō meat a special food. They hunted the birds for their meat, and also for their skins and feathers, which were used to make beautiful and warm cloaks. These cloaks were highly valued. Kākāpō feathers were also used to decorate weapons.

Even though they were hunted, kākāpō were also seen as loving pets by the Māori. Early European settlers also noted how friendly and dog-like kākāpō could be.

Kākāpō in the Media

The conservation story of the kākāpō has made it very famous. Many books and documentaries have been made about them.

One of the most famous moments was when a kākāpō named Sirocco tried to mate with a TV presenter's head in a BBC documentary! This video was seen by millions around the world, making Sirocco a "spokes-bird" for New Zealand wildlife conservation. Sirocco even inspired the "party parrot" emoji!

The kākāpō has been featured in many nature documentaries, including those by Sir David Attenborough. It was also voted New Zealand's "Bird of the Year" in both 2008 and 2020.

See also

In Spanish: Kakapo para niños

In Spanish: Kakapo para niños

- Cats in New Zealand

- Conservation in New Zealand

- Island syndrome

Images for kids

-

Lithograph by David Mitchell that accompanied Gray's original 1845 description