Hongi Hika facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hongi Hika

|

|

|---|---|

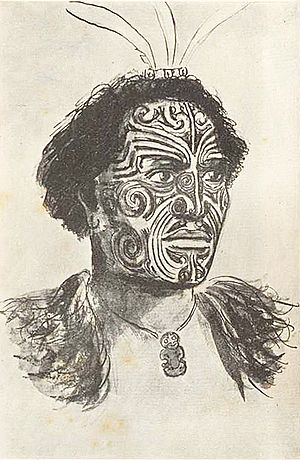

Hongi Hika, a sketch of an 1820 painting

|

|

| Born | c. 1772 Kaikohe, New Zealand |

| Died | 6 March 1828 (aged 55–56) Whangaroa, New Zealand |

| Allegiance | Ngāpuhi |

| Rank | Rangatira |

| Battles/wars | Musket Wars |

| Spouse(s) |

|

Hongi Hika (around 1772 – 6 March 1828) was a powerful Māori leader and war chief (called a rangatira) from the Ngāpuhi tribe (or iwi). He was very important during the early years when Europeans first started to arrive and settle in New Zealand.

Hongi Hika was one of the first Māori leaders to understand how useful European muskets (guns) could be in battles. He used these new weapons to gain control over much of northern New Zealand during the Musket Wars in the early 1800s. But he wasn't just a great fighter. Hongi Hika also welcomed Pākehā (European) settlers. He built good relationships with New Zealand's first missionaries, helped Māori learn about Western farming, and even helped write down the Māori language. He traveled all the way to England and met King George IV. His military actions, along with other Musket Wars, were a big reason why the British decided to take control of New Zealand and later signed the Treaty of Waitangi with Ngāpuhi and many other iwi.

Contents

Hongi Hika's Early Life and Battles

Hongi Hika was born near Kaikohe into a strong family of the Te Uri o Hua subtribe (called a hapū) of Ngāpuhi. His mother was Tuhikura. His father, Te Hōtete, helped Ngāpuhi expand their land from Kaikohe into the Bay of Islands. Hongi Hika later said he was born in 1772, the year explorer Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne was killed by Māori. This date is generally accepted today.

Hongi Hika became known as a military leader during the Ngāpuhi campaign against the Te Roroa hapū of Ngāti Whātua iwi between 1806 and 1808. For over 150 years, Māori had only had occasional contact with Europeans, and guns were not widely used. In 1808, Ngāpuhi used a few guns, and Hongi was there when muskets were first used in a battle by Māori. This was at the Battle of Moremonui, where Ngāpuhi were defeated. They were overwhelmed by Ngāti Whātua while trying to reload their guns. Hongi's two brothers were killed, and Hongi himself barely escaped by hiding in a swamp.

After the death of the Ngāpuhi leader Pokaia, Hongi became the main war leader for Ngāpuhi. He led a large war party (called a taua) to the Hokianga in 1812. Even though Ngāpuhi had lost at Moremonui, Hongi saw how valuable muskets could be if used smartly by trained warriors.

Meeting Europeans and a Trip to Australia

The Ngāpuhi tribe controlled the Bay of Islands, which was where most Europeans first arrived in New Zealand in the early 1800s. Hongi Hika protected the first missionaries, sailors, and settlers from Europe. He believed that trading with them would be good for his people. He became friends with Thomas Kendall, a preacher from the New Zealand Church Missionary Society. Kendall wrote that when he met Hongi in 1814, Hongi already had ten muskets and knew how to use them well, even without a teacher. Many Europeans who met Hongi were surprised by his gentle manner and kind personality. Early settlers often called him "Shungee" or "Shunghi."

In 1815, Hongi's older half-brother, Kāingaroa, died. This made Hongi the main chief (ariki) of Ngāpuhi. Around this time, Hongi married Turikatuku, who was an important advisor to him in battles, even though she became blind early in their marriage. He later also married her younger sister, Tangiwhare. Turikatuku was his favorite wife, and he always had her by his side, even in battle.

In 1814, Hongi and his nephew Ruatara visited Sydney, Australia, with Kendall. There they met Samuel Marsden, who led the Church Missionary Society. Marsden described Hongi as "a very fine character" and "uncommonly mild." Ruatara and Hongi invited Marsden to set up the first Anglican mission in New Zealand, on Ngāpuhi land. Ruatara died the next year, leaving Hongi to protect the mission at Rangihoua Bay. Other missions were also started under his protection at Kerikeri and Waimate North. While in Australia, Hongi Hika learned about European military and farming methods. He also bought muskets and ammunition.

Because Hongi protected them, more ships came to the Bay of Islands, which meant more chances for trade. Hongi was most interested in trading for muskets, but the missionaries often didn't want to trade guns. This caused some problems, but Hongi kept protecting them. He knew it was important to have a safe harbor for trade. He traded for iron farming tools, which helped his people grow more crops. These crops could then be traded for muskets. In 1817, Hongi led a war party to Thames and attacked the Ngāti Maru stronghold of Te Totara. Many people were killed or captured. In 1818, Hongi led another Ngāpuhi war party against tribes in the East Cape and Bay of Plenty. About fifty villages were destroyed, and nearly 2,000 people were captured as slaves.

Hongi encouraged the first Christian missions in New Zealand but never became a Christian himself. In 1819, he gave 13,000 acres of land at Kerikeri to the Church Missionary Society in exchange for 48 axes. He also helped the missionaries create a written form of the Māori language. Hongi, like other Māori, saw his relationship with the missionaries as a way to trade and benefit his people. Very few Māori became Christian for about ten years. Most northern Māori only converted after Hongi's death. He protected Thomas Kendall when Kendall left his wife and took a Māori wife. Later in life, Hongi became frustrated with Christian teachings of humility and non-violence. He said Christianity was only for slaves.

Trip to England and More Battles

In 1820, Hongi Hika, his nephew Waikato, and Kendall traveled to England on a whaling ship. Hongi spent five months in London and Cambridge. His facial tattoos (called moko) made him famous there. During his trip, he met King George IV, who gave him a suit of armor. Hongi later wore this armor in battles in New Zealand, which scared his enemies. In England, he continued to help Professor Samuel Lee write the first Māori–English dictionary. Because of Hongi Hika's northern dialect, written Māori still has a northern sound today. For example, the "f" sound in Māori is written as "wh."

Hongi Hika returned to the Bay of Islands on July 4, 1821. He traveled with Waikato and Kendall. He reportedly traded many of the gifts he received in England for muskets in New South Wales, which upset the missionaries. He also picked up hundreds of muskets that were waiting for him. These muskets had been ordered by Baron Charles de Thierry, whom Hongi met in England. De Thierry traded the muskets for land in the Hokianga, though his claim to the land was later disputed. Hongi was able to get the guns without paying for them. He also got a lot of gunpowder, bullets, swords, and daggers.

With these new weapons, Hongi quickly led a force of about 2,000 warriors. Over 1,000 of them had muskets. They attacked the Ngāti Pāoa chief Te Hinaki at Mokoia and Mauinaina pā (Māori forts) on the Tamaki River (now Panmure). This battle resulted in the death of Hinaki and many Ngāti Paoa people. This attack was revenge for a defeat Ngāpuhi had suffered around 1795. Hongi wore the suit of armor given to him by King George VI during this battle. It saved his life, leading to rumors that he could not be harmed. Hongi and his warriors then attacked the Ngāti Maru pā of Te Tōtara. Hongi pretended to want peace, then attacked that night when the Ngāti Maru guards were not ready. Hundreds were killed, and as many as 2,000 were captured and taken back to the Bay of Islands as slaves. This was also revenge for a defeat in 1793.

In early 1822, Hongi led his force up the Waikato River. After some initial success, he was defeated by Pōtatau Te Wherowhero. However, he won another victory at Orongokoekoea. In 1823, he made peace with the Waikato iwi and invaded Te Arawa territory in Rotorua. His warriors carried their large canoes (called waka) overland into Lake Rotoehu and Lake Rotoiti.

In 1824, Hongi Hika attacked Ngāti Whātua again. He lost 70 men, including his eldest son Hāre Hongi, in the battle of Te Ika a Ranganui. This defeat was a disaster for Ngāti Whātua. The survivors moved south, leaving behind the rich land of Tāmaki Makaurau (the Auckland isthmus) with its large harbors at Waitematā and Manukau. This land had belonged to Ngāti Whātua for over a hundred years. Hongi Hika left Tāmaki Makaurau almost empty as a buffer zone to the south. Fifteen years later, when Governor William Hobson wanted to move his new government away from the Bay of Islands, he was able to buy this land cheaply from Ngāti Whātua. This is where Auckland, New Zealand's main city, was built. In 1825, Hongi got revenge for the earlier defeat at Moremonui in the battle of Te Ika-a-Ranganui, though both sides lost many people.

Hongi Hika's Final Years and Death

In 1826, Hongi Hika moved from Waimate to conquer Whangaroa and start a new settlement. This was partly to punish the Ngāti Uru and Ngāti Pou tribes for bothering the Europeans at Wesleydale, the Wesleyan mission at Kaeo. In January 1827, some of his warriors, without his knowledge, ransacked the Wesleydale mission, and it was abandoned.

In January 1827, Hongi Hika was shot in the chest during a small fight in the Hokianga. A few days later, when he returned to Whangaroa, he found that his wife Turikatuku had died. Hongi lived for 14 more months, and at times people thought he might recover. He kept planning for the future, inviting missionaries to Whangaroa, planning a trip to Waikato, and hoping to capture the harbor at Kororāreka (Russell). He would invite people to listen to the wind whistling through his lungs, and some even claimed they could see right through him. He died from an infection on March 6, 1828, at Whangaroa. Five of his children survived him, and his final burial place was kept a secret.

Hongi Hika's death seemed to be a turning point for Māori society. Unlike what usually happened when an important chief died, no attack was made by neighboring tribes to get revenge for Hongi Hika's death. Settlers who had been under his protection were worried they might be attacked, but nothing happened. The Wesleyan mission at Whangaroa was closed and moved to Māngungu near Horeke.

Frederick Edward Maning, a European who lived among Māori, wrote about Hongi Hika. He said that Hongi warned on his deathbed that if "red coat" soldiers (British soldiers) landed in Aotearoa (New Zealand), his people should "make war against them." Another missionary, James Stack, recorded a conversation where it was said that Hongi Hika told his followers to fight against any enemy, no matter how many. His dying words were "kia toa, kia toa – be brave, be brave! Thus will you revenge my death, and thus only do I wish to be revenged."

Hongi Hika's Legacy

Hongi Hika is remembered as a great warrior and leader during the Musket Wars. Some historians say his military success was mostly because he got muskets. Others say he was a very skilled general. He was smart enough to get European weapons and change how Māori war forts (pā) and fighting methods were designed. These changes surprised British and colonial forces later during Hone Heke's Rebellion in 1845–46. Hongi Hika's campaigns caused big changes in society. But he also helped by encouraging early European settlement, improving farming, and helping to create a written version of the Māori language.

Hongi Hika's actions changed the balance of power in many areas of New Zealand, including Waitemata, Bay of Plenty, Tauranga, Coromandel, Rotorua, and Waikato. His campaigns and those of other musket warriors led to many tribes moving and making new land claims. This later made land disputes complicated in the Waitangi Tribunal. For example, the Ngāti Whātua occupation of Bastion Point in 1977–78 was related to these historical events.

Hongi Hika never tried to set up a long-term government over the tribes he conquered. He rarely tried to keep control of territory permanently. It's likely his goals were to increase his own respect and influence (called mana) as a warrior. He is said to have stated during his visit to England, "There is only one king in England, there shall be only one king in New Zealand." But if he wanted to become a Māori king, it never happened. In 1828, Māori did not have a national identity; they saw themselves as belonging to separate iwi. It would be 30 years before the Waikato iwi recognized a Māori king. That king was Te Wherowhero, a man who had gained his mana by defending the Waikato against Hongi Hika in the 1820s.

Hongi Hika's second son, Hāre Hongi Hika (who took his older brother's name after his death in 1825), signed the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand in 1835. He became an important leader after his father's death. He was one of only six chiefs to sign the declaration by writing his name, not just making a mark. He was also important in Māori struggles for sovereignty in the 1800s and helped open the Te Tii Waitangi Marae in 1881. He died in 1885. Hongi Hika's daughter Hariata (Harriet) Rongo married Hōne Heke in 1837. She had her father's confidence and drive, and brought her own mana to the marriage.

Hongi Hika is shown leading a war party against the Te Arawa iwi in a 2018 music video for the New Zealand thrash metal band Alien Weaponry's song "Kai Tangata."

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |