Natural history of New Zealand facts for kids

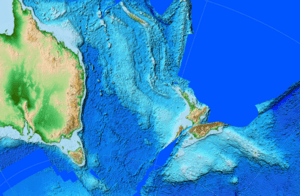

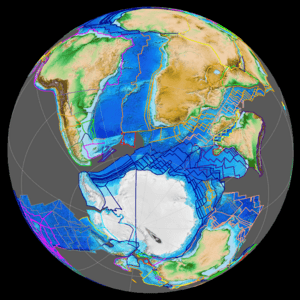

New Zealand's amazing natural story started when a huge piece of land called Zealandia broke away from a giant continent named Gondwana. This happened about 85 million years ago! Before then, Zealandia was connected to Australia and Antarctica. After it separated, New Zealand's plants, animals, and landscapes developed mostly on their own.

This natural history changed around 1300 AD when people first arrived. Since then, many of New Zealand's special native species have sadly become extinct.

When Gondwana broke apart, the new landmasses, including Zealandia, shared similar plants and animals. Zealandia started moving away from Australia and Antarctica about 85 million years ago. By 70 million years ago, the separation was complete. Zealandia has been moving north ever since, changing its shape and climate. Today, New Zealand still has some plants and animals from Gondwana, like podocarps, southern beeches, unique insects, birds, frogs, and the tuatara. However, it has lost others, like the ancient Saint Bathans mammal. Many new species have also arrived over time.

During a period called the Oligocene (about 33.9 to 23 million years ago), Zealandia's land area was at its smallest. Some scientists thought it might have been completely underwater. But most now agree that some low-lying islands remained. These islands were probably about a quarter the size of New Zealand today.

Contents

- Zealandia: Before the Big Split (85 Million Years Ago)

- Zealandia Drifts Away (85–66 Million Years Ago)

- Swamps and Volcanoes (66 to 33.9 Million Years Ago)

- New Zealand's Shallow Seas (33.9 to 23 Million Years Ago)

- Mountains, Fossils, and Ancient Animals (23 to 2.6 Million Years Ago)

- Volcanoes and Ice Ages (2.6 Million Years Ago to Today)

Zealandia: Before the Big Split (85 Million Years Ago)

In the late Cretaceous period, Gondwana was smaller than before. But the lands that would become Australia, Antarctica, and Zealandia were still joined. Many of the animals we call 'Gondwanan fauna' today first appeared in the Cretaceous. At this time, Zealandia had a mild climate and was mostly flat. There were no tall mountains yet.

Ancient Animals of Gondwana

Fossils found in Australia suggest that 110 million years ago, Australia had many different monotremes (like echidnas and platypuses). But it did not have any marsupials (like kangaroos). Marsupials seem to have first appeared in the northern part of the world. A 100-million-year-old marsupial fossil was found in Utah, USA. Marsupials then spread to South America and Gondwana.

The first signs of mammals (both marsupials and placental mammals) in Australia are from 55 million years ago. These were found at a fossil site in Queensland. Since Zealandia had already broken away by then, this explains why New Zealand's fossil record does not show any native land-dwelling marsupials or placental mammals.

Dinosaurs continued to thrive during this time. As flowering plants became more common, some conifer trees and specialized plant-eating dinosaurs disappeared from Gondwana. But general plant-eaters, like some types of sauropodomorph dinosaurs, did well. The Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event killed off all dinosaurs except birds. However, plant life in Gondwana was not much affected.

Some ancient mammals, called Gondwanatheria, lived across Gondwana (South America, Africa, Madagascar, India, and Antarctica). Two groups of placental mammals, Xenarthra and Afrotheria, also came from Gondwana. They likely started to evolve separately around 105 million years ago when Africa and South America split.

Ancient Plants of Gondwana

Angiosperms first appeared in the northern part of Gondwana and southern Laurasia during the Early Cretaceous. They then spread all over the world. The southern beeches are important members of these early flowering plants. Fossils of pollen from the Late Cretaceous show that some plants evolved across all of Gondwana. Others started in Antarctica and then spread to Australia. Nothofagus fossils have also been found in Antarctica.

The laurel forests in Australia, New Caledonia, and New Zealand have many species related to those in South America. This connection happened through the ancient Antarctic flora. These include gymnosperms and the deciduous Nothofagus trees. Also, the New Zealand laurel, Corynocarpus laevigatus, and Laurelia novae-zelandiae are part of this group. At this time, Zealandia was mostly covered in forests of podocarps, araucarian pines, and ferns.

Zealandia Drifts Away (85–66 Million Years Ago)

The landmass that included Australia and New Zealand split from Antarctica in the late Cretaceous (95–90 million years ago). Then, Zealandia separated from Australia around 85 million years ago. This split began in the south and eventually formed the Tasman Sea. By about 70 million years ago, Zealandia's land was fully separated from Australia and Antarctica. However, we don't know exactly when the land above sea level fully separated. For some time, only shallow seas might have divided Zealandia and Australia in the north. Dinosaurs continued to live in New Zealand. They had about 10–20 million years to evolve into unique species after the separation from Gondwana.

In the Cretaceous, New Zealand was much further south than it is today (about 80 degrees south). But it, and much of Antarctica, was covered in trees. This was because the climate 90 million years ago was much warmer and wetter.

New Zealand's native land animals today do not include land mammals (except bats) or snakes. Neither marsupials nor placental mammals evolved in time to reach Australia before the split. A very old type of mammal called multituberculates might have been able to cross to New Zealand using a land bridge. We are less sure about snakes because their fossil record is poor. It's unclear if they were in Australia before the Tasman Sea opened. Ratite birds (like ostriches and emus) evolved around 80 million years ago. They might have been present in Zealandia at this time.

Swamps and Volcanoes (66 to 33.9 Million Years Ago)

At the start of the Paleocene epoch, New Zealand's living things were recovering from the dinosaur extinction. The species that survived began to spread into the empty spaces. The average temperature dropped slightly at the start of the Paleocene. This led to changes in the types of trees that formed the forest canopy. Zealandia was mostly covered by shallow seas, with low-lying land and swamps. The oldest penguin fossil in the world, along with other ancient sea birds, has been found in New Zealand from this time.

The Tasman Sea continued to grow until the early Eocene (53 million years ago). The western half of Zealandia then joined with Australia to form the Australian Plate (40 million years ago). Because of this, a new plate boundary formed within Zealandia. This boundary was between the Australian Plate and the Pacific Plate. This caused volcanoes to become active, forming islands north and west of present-day New Zealand. New Zealand was low-lying due to this stretching of the land, and swamps became very common. Today, we see these ancient swamps as large coal seams in the rocks.

Many scientists believe that the separation of Antarctica and the formation of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current caused Antarctica to become covered in ice. This also led to global cooling in the Eocene epoch. Ocean models show that the opening of these two passages (around Antarctica) limited how much heat reached the poles. This caused sea surface temperatures to drop by several degrees. Other models show that CO2 levels also played a big part in Antarctica's glaciation. Scientists often say the Antarctic Circumpolar Current started at the Eocene/Oligocene boundary.

Whales became fully marine animals by 40 million years ago. New Zealand's oldest whale fossils are from 35 million years ago.

New Zealand's Shallow Seas (33.9 to 23 Million Years Ago)

From the early Oligocene, when the Zealandia landmass was mostly underwater, almost all of New Zealand's rocks were formed in the sea. There are very few land-based sediments from the Oligocene, and they are hard to date. Some people thought that Zealandia was completely underwater at one point. If so, all land plants and animals would have arrived later.

However, studies of the DNA of 248 different New Zealand species show something different. They suggest that many species have been in New Zealand for 50 million years or more. About 74 of these species seem to have survived the Oligocene in New Zealand. There is no sign that many species died out before the Oligocene, or that many new ones arrived just after. This strongly suggests that New Zealand was never completely submerged.

While there isn't a clear sign of many species dying out in the Oligocene, the limited genetic diversity in kiwis, moas, and New Zealand wrens hints at a genetic bottleneck. This means their populations became very small around the time of maximum submersion. New Zealand at this time probably had only low-lying islands with few different types of habitats.

Significant uplift of land happened in the mid-Oligocene (around 32–29 million years ago) in the area of the modern Canterbury Basin. Here, ancient river channels cut through the early Oligocene Amuri Limestone, leading east towards the present Bounty Trough.

The North and South Islands have been separate for most of the last 30 million years. This has allowed different subspecies to develop on each island.

Mountains, Fossils, and Ancient Animals (23 to 2.6 Million Years Ago)

Major uplift began along the Alpine Fault. This fault started to form the hills and mountains that became the Southern Alps.

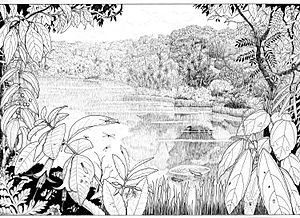

Foulden Maar is a special type of volcano that preserved many fossils. It holds a wide variety of freshwater fish, insects, plants, and fungi from a lake 23 million years ago. It is the only known maar of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere and is one of New Zealand's most important fossil sites. Fossil pollen and spores suggest a warm, humid, sub-tropical rainforest. This forest had tall canopy trees, with smaller shrubs and ferns underneath. The climate was like modern-day south-eastern Queensland, which is a humid sub-tropical area. Some of the species found there no longer grow in New Zealand. The lake had small and large galaxiid fish, eels, and ducks. It likely also had crocodiles.

The Saint Bathans Fauna provides a detailed look at New Zealand's land animals in the Miocene epoch. It shows that small land mammals and crocodiles once lived here but have since become extinct. The earliest remains of moas come from the Miocene Saint Bathans Fauna. From eggshells and leg bones, we know there were at least two species of already quite large moas at that time.

The boundaries of the Pliocene epoch are not marked by a single worldwide event. Instead, they are based on regional changes between the warmer Miocene and the cooler Pliocene. The end of the Pliocene is set at the start of the Pleistocene ice ages. Uplift increased along the Alpine Fault, forming the Southern Alps. This global cooling, combined with the rising mountains, caused many plant groups to die out locally. These plants are now still found in New Caledonia. The new habitats created in the mountains were filled by species migrating from Australia and those that could quickly adapt.

Volcanoes and Ice Ages (2.6 Million Years Ago to Today)

The ice age began 2.6 million years ago, at the start of the Pleistocene epoch. It is defined by the presence of large ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica. During warmer times, sea levels were higher than today. This created raised beaches around New Zealand. New Zealand's plant life is still recovering from the last glacial maximum. About 2 million years ago, the stretching of the land and subduction under the North Island formed the Taupo Volcanic Zone. This led to the central North Island having soils low in cobalt, which makes it hard for forests to grow. One of the largest eruptions was the Lake Taupo eruption in 186 AD.

Since the last glacial maximum, there have been three main climate periods. The coldest period was from 28,000 to 18,000 years ago. An intermediate period followed from 18,000 to 11,000 years ago. Our current warmer climate, the Holocene Inter Glacial, has been for the last 11,000 years. In the coldest period, global sea levels were about 130 meters lower than today. This made most of New Zealand a single large island. It also exposed huge parts of the continental shelf that are now underwater. Temperatures were about 4–5 °C lower than today. Much of the Southern Alps and Fiordland were covered in glaciers. Most of the rest of New Zealand was covered in grass or shrubs due to the cold, dry climate.

These large areas of exposed land with little plant cover led to more wind erosion. This deposited loess (windblown dust). The loss of forests meant many canopy tree species were limited to the northern parts of the country. The kauri tree, for example, was only found in Northland at that time. It has slowly moved south over the last 7,000 years, reaching its current limit about 2,000 years ago.

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |