South Polar region of the Cretaceous facts for kids

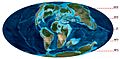

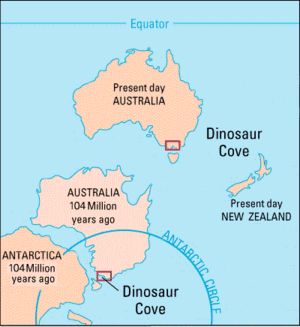

The South Polar region during the Cretaceous period (about 145 to 66 million years ago) was very different from today. It was made up of a huge continent called East Gondwana, which included what we now know as Australia and Antarctica. This land was much warmer than Antarctica is today.

Because it was warmer, there were no permanent ice sheets. Instead, the South Pole was covered in thick polar forests. These forests were mostly filled with conifers (like pine trees), cycads (palm-like plants), and ferns. They needed a mild climate and lots of rain to grow.

Many unique animals lived in this region. For example, there were small, plant-eating dinosaurs called hypsilophodonts. The last known labyrinthodont amphibian, a giant frog-like creature named Koolasuchus, also lived here. As Antarctica became more isolated, its ocean areas developed a special group of sea creatures known as the Weddellian Province.

Contents

Ancient Landscapes

How the Land Changed

The land that is now the southern Antarctic Peninsula had a lot of volcanic rock. This shows there was a huge volcanic event during the Middle Cretaceous. This area has many fossils of plants and mollusks from the Early Cretaceous and Late Jurassic periods. The Antarctic Peninsula was always active with volcanoes because a large tectonic plate was sliding underneath it.

Important fossil sites include the Santa Marta Formation on James Ross Island near the Antarctic Peninsula. This area has many different land plants and animals from the Late Cretaceous polar region. Seymour Island is another key site, where fossils of vertebrates (animals with backbones) and invertebrates (animals without backbones), like plesiosaurs, have been found. Other fossil sites on James Ross Island include the Snow Hill Island Formation, the Lopez de Bertodano Formation, and the Hidden Lake Formation.

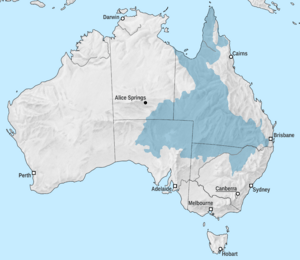

In Australia, the Eumeralla Formation at Dinosaur Cove and the Wonthaggi Formation in Victoria have many dinosaur fossils and footprints from the Early Cretaceous. New Zealand's Tahora Formation also shows us what reptiles lived there during the Cretaceous.

A large inland sea called the Eromanga Sea covered parts of Australia in the Early Cretaceous. It had lagoons and rivers in the south and a bay in the east. When India moved away from Australia, another sea formed in the Perth Basin. As Australia and Antarctica slowly drifted apart, a new sea formed between them.

Plant Life in the Polar Forests

The Cretaceous period was generally very warm around the world. This was because there was a lot of carbon dioxide and methane in the air, which are greenhouse gases. This warmth meant that the polar regions didn't have permanent ice. Even though carbon dioxide levels dropped later in the Cretaceous, some scientists think small ice sheets might have formed sometimes. More volcanic activity could have kept the Earth warmer overall. Temperatures might have been up to 15°C (27°F) warmer than they are today!

Early Cretaceous Plants

In the Early Cretaceous, East Gondwana (Australia, Antarctica, and Zealandia) began to break away from South America. India and Madagascar also started to separate. The warm, tropical zone might have reached as far south as 32°S, allowing trees to grow all year round in the Antarctic polar forests. Discoveries of large evergreen and deciduous trees suggest mild temperatures with moderate seasons, without widespread freezing, at least between 70°S and 85°S. However, it's also possible these plants only grew during the warm summer months. We know a lot about the plants of East Gondwana from pollen and leaf compressions found in the northern Antarctic Peninsula. Depending on the exact location, the polar night (when the sun doesn't rise) could have lasted from six weeks to over four months.

However, rocks from the Early Cretaceous Wonthaggi Formation in southeastern Australia show signs of seasonally frozen ground. This area was around 78°S, meaning it had one to three months of darkness in winter. It was likely a floodplain fed by glaciers. Evidence of cold climates and possibly glaciers was also found in sediments in the Eromanga Basin in central Australia, which was between 60°S and 80°S in the Early Cretaceous. This basin was a huge inland sea. Still, some similar formations could have been made by simple debris flows, so it's not certain if glaciers were always there. The total polar ice cover during the Mesozoic Era might have been only a third of what it is today, but cold spells with freezing temperatures probably happened throughout the Early Cretaceous.

Late Cretaceous Plants

The tops of the polar forests around what is now Alexander Island (around 75°S in the Middle Cretaceous) were mostly evergreen trees, especially araucarian and podocarp conifers. It's believed these trees stayed quiet during the polar winters and grew during the long summer days with the midnight sun.

Fossils of flowering plants from about 80 million years ago in the Late Cretaceous suggest there were temperate forests, similar to those in modern Australia, New Zealand, and southern South America. Some flower fossils were found near 60°S. At this latitude, the area might have had polar winters and seasonal weather, but the flowers suggest an average yearly temperature of 8–15°C (46–59°F) and a rainy climate.

Pollen from southeastern Australia matches plants living in Australia today, like conifers, flowering plants that like a lot of rain, and sclerophyllous scrublands. This means the landscape was a mix of rainforest and open bushland. By looking at the tree rings on fossil trees, scientists found that the Antarctic polar forests got cooler during the Maastrichtian age (72 to 66 million years ago). The average yearly temperature dropped from 7°C (45°F) to a more extreme 4–8°C (39–46°F). These plants likely survived the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event (which killed off most life 66 million years ago) on the volcanic Antarctic Peninsula. Plant fossils from 60 million years ago on Seymour Island are thought to be the ancestors of temperate plants found in modern Australia and South America.

Ancient Animals

Dinosaurs

Birds

Fossils of early modern birds (called Neornithes) are rare from the Mesozoic Era. Most bird groups developed much later in Antarctica. However, the discovery of Vegavis, a goose-like bird from the Late Cretaceous found on Vega Island, shows that major modern bird groups were already around. A leg bone from a bird similar to a seriema was also found on Vega Island. Bird footprints in Dinosaur Cove, which were larger than most Cretaceous bird species, suggest there were many big birds like enantiornithes or ornithurines in the Early Cretaceous.

Two diving birds, possibly early loons, were found in Late Cretaceous Chile and Antarctica: Neogaeornis and Polarornis. Polarornis might have been able to both dive and fly. The earliest penguins, Crossvallia and Waimanu, are known from 61–62 million years ago. However, genetic studies suggest penguins first appeared in the Late Cretaceous. Since these penguins lived so close to the extinction event, they either evolved before it or very quickly afterward.

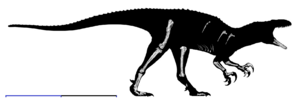

Non-flying Dinosaurs

Dinosaur fossils are rare in the South Polar region. Key fossil sites include the James Ross Island group, Beardmore glacier in Antarctica, Roma, Queensland, Mangahouanga stream in New Zealand, and Dinosaur Cove in Victoria, Australia. The dinosaur remains from this region are often just small pieces, making them hard to identify. For example, there are debates about whether some fossils are from an Allosaurus or an Abelisaurus, or if Serendipaceratops is a ceratopsian or an ankylosaur. The theropod Timimus is also hard to classify.

When the supercontinent Pangaea existed in the Jurassic, major dinosaur groups spread all over the world. Even after Pangaea broke up, some closely related dinosaurs were found in the South Polar region and elsewhere, despite being separated by the Tethys Ocean. However, dinosaur groups that spread across all of Gondwana during the Cretaceous would have had to use a land bridge connecting Australia to South America through Antarctica. The South Polar iguanodontian Muttaburrasaurus is most closely related to European rhabdodontids, which were common in Europe during the Late Cretaceous. The Cretaceous South Polar Kunbarrasaurus is considered the most primitive ankylosaur, which is important because ankylosaurs are found in both Gondwana and Laurasia. Dromaeosaurs (raptor-like dinosaurs) are known from Antarctica, suggesting they were a remaining group from a time when they lived worldwide. Despite these apparent migrations, it's unlikely that South Polar dinosaurs left the polar forests during winter. They were either too big (like ankylosaurs) or too small (like troodontids) to travel long distances, and a large sea blocked migrations in the Late Cretaceous. Some dinosaurs, like the theropod Timimus, might have hibernated to cope with winter.

The most common and diverse dinosaurs found so far are the hypsilophodont-like dinosaurs. They make up half of all dinosaur types found in southeastern Australia, which is unusual compared to more tropical regions. This might mean they had an advantage in the poles. Being small with teeth for grinding, they probably ate low-lying plants like lycopods and podocarp seed pods. The hypsilophodont-like Leaellynasaura had very large eye sockets, bigger than those of tropical hypsilophodont-like dinosaurs. This suggests it might have had excellent night vision, meaning Leaellynasaura and perhaps other hypsilophodont-like dinosaurs lived in the polar areas all year round, including during the dark polar winters. Its bones grew continuously, meaning it didn't hibernate. This was possible if it was warm-blooded or if it dug burrows. However, it's also possible the large eyes were just a feature of young dinosaurs or a birth defect, as only one specimen is known.

Although remains are scarce and identification is often uncertain, Victorian theropod fossils have been linked to seven different groups: Ceratosauria, Spinosauria, Tyrannosauroidea, Maniraptora, Ornithomimosauria, and Allosauroidea. However, tyrannosauroids are not known from other Gondwanan continents and are more common in northern Laurasia. Unlike other Gondwanan continents where the top predators were abelisaurids and carcharodontosaurids, the discovery of Australovenator, Rapator, and an unnamed species in Australia suggests that megaraptorans were the top predators of East Gondwana. The tail bones of an unknown theropod, nicknamed "Joan Wiffen's theropod", were found in Late Jurassic/Early Cretaceous rocks in New Zealand.

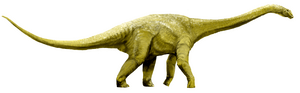

Three titanosaurs (Savannasaurus, Diamantinasaurus, and Wintonotitan) and one macronarian (Austrosaurus) found in the Winton Formation make up the sauropod (long-necked, plant-eating dinosaurs) group of Cretaceous Australia. However, these huge creatures probably avoided the polar regions, as their remains are completely missing from Southeast Australia, which was in the South Polar region during the Cretaceous. Still, it's likely that at least the titanosaurs migrated to Australia from South America, which would have required them to pass through Antarctica, since titanosaurs evolved after Pangaea broke up. It's possible the Bonarelli Event in the Middle Cretaceous made Antarctica warmer and more welcoming for sauropods. These dinosaurs probably ate the fleshy seeds of podocarp and yew trees, as well as the common forked ferns of the time. Austrosaurus might be a leftover from Middle Jurassic sauropods, appearing more primitive than other Cretaceous sauropods. It's a mystery why more primitive sauropods lasted longer than more advanced ones. It's possible that after becoming extinct near the equator, dinosaurs preferred the polar regions more.

After the Dinosaurs (Paleocene)

After an asteroid hit Earth, the resulting "impact winter" is thought to have killed off the dinosaurs and much of the life from the Mesozoic Era in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. However, in Antarctic or Australian sediments, there isn't a sudden disappearance of plant and bivalve (shellfish) fossils during this time. This suggests the impact might have been less severe in the South Polar region. Since the dinosaurs and other animals of the Cretaceous polar regions were good at living in long periods of darkness and cold, some scientists think this community might have survived the extinction event.

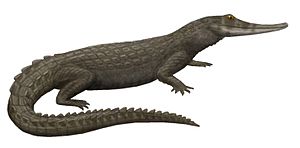

Rivers and Lakes

The last temnospondyls, a group of giant amphibians that mostly died out after the Triassic period, lived in the South Polar region into the Early Cretaceous. Koolasuchus, perhaps the last temnospondyl, is thought to have survived in areas too cold for their rivals, the neosuchians (a group of reptiles that includes modern crocodilians). Neosuchians become inactive in water below 10°C (50°F). Although neosuchians are known from Cretaceous Australia, it's thought they stayed away from the polar region, arriving in Australia by sea rather than over land.

It's likely the temnospondyls lived in the freshwater systems of polar Australia until the Bonarelli Event around 100 million years ago. This event increased temperatures and allowed neosuchians to live in Antarctica. These neosuchians, which were no more than 2.5 meters (8.2 feet) long as adults, probably caused the extinction of the temnospondyls, along with more developed ray-finned fish that might have eaten their larvae. The arrival of neosuchians in the region suggests that average winter temperatures were above 5.5°C (42°F), with an average yearly temperature over 14.2°C (58°F). However, polar neosuchians are only known from one nearly complete skeleton of Isisfordia; other neosuchian remains are from unknown species.

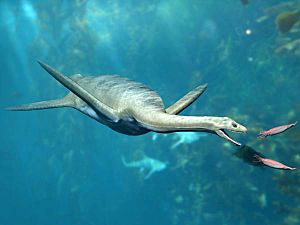

Plesiosaurs lived in freshwater rivers and estuaries. Their remains, mostly teeth, have been found in southeastern Australia from the Late Cretaceous. However, they were never fully described because the remains are too few. The teeth are similar to those of pliosaurs, especially rhomaleosaurids and Leptocleidus, which died out in the Early Cretaceous. This suggests the polar freshwater systems might have been a safe place for pliosaurs during the Cretaceous. Unlike modern marine reptiles, these South Polar plesiosaurs probably handled colder waters better.

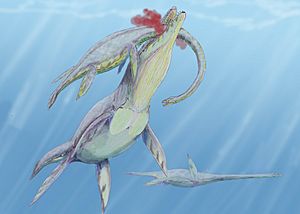

Oceans

Early to Middle Cretaceous marine reptile fossils from South Australia include five families of plesiosaurs (Cryptoclididae, Elasmosauridae, Polycotylidae, Rhomaleosauridae, and Pliosauridae) and the ichthyosaur family Ophthalmosauridae. The discovery of several young plesiosaur remains suggests they used the nutrient-rich coastal waters as safe places to give birth. The cold water might have kept predators like sharks away. Most of the plesiosaurs found lived all over the world, but some unique ones, like Opallionectes and a possible new species of cryptoclidid, lived only there. A debated species of elasmosaurid, Woolungasaurus, was named in 1928, one of the earliest descriptions of an Australian marine reptile. Many fossils of molluscs, gastropods, ammonites, bony fish, chimaerids, and squid-like belemnites have also been found. The coastal area might have frozen in winter. These reptiles might have moved north during winter, had a faster metabolism than tropical reptiles, hibernated in freshwater areas like modern American alligators, or been warm-blooded like modern leatherback sea turtles. The lower number of plesiosaurs and higher number of ichthyosaurs and sea turtles in more northern parts of Australia suggests plesiosaurs preferred colder areas.

Several Late Cretaceous oceanic plesiosaurs and mosasaurs have been found in New Zealand and Antarctica. Some, like Mauisaurus, were unique to the region, while others, like Prognathodon, lived all over the world. Elasmosaurs and pliosaurs are known from one to three species in this area. The discovery of three cryptoclidids in the Southern Hemisphere (Morturneria from Antarctica, Aristonectes from South America, and Kaiwhekea from New Zealand) shows that this family became more diverse in the Late Cretaceous of this region. This might also suggest that the early Southern Ocean was becoming more productive.

Pterosaurs

Two groups of pterosaurs (flying reptiles) are found in Early Cretaceous Australia: Pteranodontoidea and Ctenochasmatoidea. Their remains are mostly from the Toolebuc Formation and areas of Queensland and New South Wales. Scientists think at least six types of pterosaurs lived in Cretaceous Australia, but many fossils are too broken to identify exactly. Fossils were found in shallow-water areas and lagoons, suggesting they ate fish and other water animals. Ctenochasmatids were the only archaeopterodactyloids to survive into the Cretaceous. The only pterosaur tooth fossils found in Australia from the Early Cretaceous belong to Mythunga and a possible Late Cretaceous anhanguerid. Mythunga is estimated to have had a 4.5-meter (15-foot) wingspan, much larger than any other archaeopterodactyloid found. However, it's possible this pterosaur is more closely related to the Anhangueridae or Ornithocheiridae. Since pterosaurs could fly, they might not have needed to cross a land bridge through the polar regions to get to Australia, meaning they might not have lived in the South Polar region at all.

Of the Late Cretaceous pterosaurs, only remains belonging to the family Azhdarchidae (found in the Carnarvon Basin and Perth Basin in Western Australia) were assigned to a specific group. A possible ornithocheirid was found in Late Cretaceous Western Australia, even though this family was thought to have died out in the Early Cretaceous.

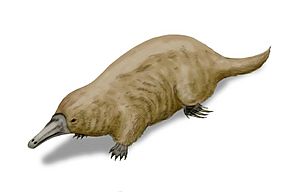

Mammals

Seven mammals have been discovered from Early Cretaceous Australia: an undescribed platypus-like animal, Kryoryctes, Kollikodon, Ausktribosphenos, Bishops, Steropodon, and Corriebaatar. All of these were unique to Australia at that time. It's likely that mammals crossed the Antarctic land bridge between Australia and South America in the Early Cretaceous. The ancestors of Australia's unique mammals probably arrived during the Jurassic across the supercontinent Pangaea.

Invertebrates

Many fossils of insects and crustaceans have been found in South Polar Cretaceous sediments in New Zealand. The Late Cretaceous Monro Conglomerate was located at 68°S and provided fossils of Helastia, and the crab Hemioon novozelandicum was found in the Swale Siltstone, located at 76°S during the late Albian age. Several insect specimens were also found in the Tupuangi Formation of the Chatham Islands at a latitude of 79°S during the Cenomanian to Turonian ages.

Images for kids

-

Paleogeography of the Late Cretaceous (90 Ma); the Antarctic Circle is at 60°S

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |