Broad-billed parrot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Broad-billed parrot |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Sketch of two individuals in the Gelderland ship's journal, 1601 | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittaculidae |

| Genus: | †Lophopsittacus Newton, 1875 |

| Species: |

†L. mauritianus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Lophopsittacus mauritianus (Owen, 1866)

|

|

|

|

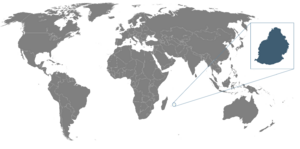

| Location of Mauritius in blue | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

|

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The broad-billed parrot or raven parrot (Lophopsittacus mauritianus) was a very large extinct parrot. It belonged to the family Psittaculidae. This unique bird lived only on the island of Mauritius in the Mascarenes.

Sailors first called it the "Indian raven" in 1598. Only a few old descriptions and three drawings of it exist. Scientists first described it in 1866 from a subfossil jawbone. Later, a detailed sketch from 1601 was found. This drawing helped connect the old stories with the fossil bones.

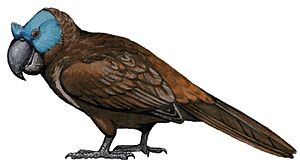

The broad-billed parrot had a huge head and a special crest of feathers on its forehead. Its beak was very big, like that of a hyacinth macaw. This strong beak helped it crack open hard seeds. Male parrots were much larger than females. The exact colors are not fully known. But one old description says it had a blue head and possibly a red body and beak. Scientists think it was not a strong flier, but it could fly. This parrot became extinct in the late 1600s. This happened because of deforestation, new animals that hunted them, and possibly hunting.

Contents

Discovering the Broad-Billed Parrot

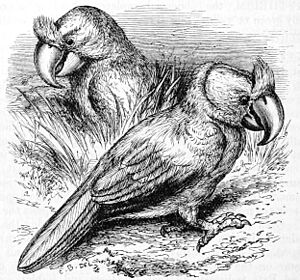

Dutch sailors first wrote about the broad-billed parrot in 1598. These reports were published in 1601. They also included the first drawing of the bird. The drawing's caption called it an "Indian Crow." It said the bird was "more than twice as big as the parroquets" and had "two or three colours."

Dutch sailors on Mauritius called these parrots "Indian ravens." They did not give many helpful details. This caused confusion for later scientists. Some thought it was a type of hornbill because of a bump on its head in one drawing. But no hornbill bones have ever been found on Mauritius.

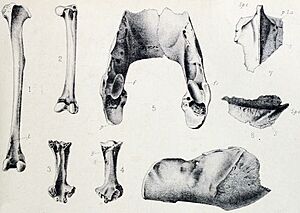

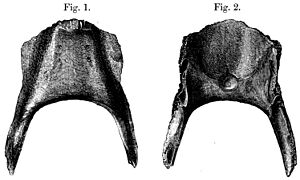

The first actual bone of the broad-billed parrot was a fossil jawbone. It was found with the first dodo bones in a swamp. In 1866, British scientist Richard Owen described this jaw. He named the bird Psittacus mauritianus. Owen also gave it the common name "broad-billed parrot."

In 1868, a journal from the Dutch ship Gelderland was found. It had a drawing of the parrot. German scientist Hermann Schlegel realized this drawing matched Owen's description. In 1875, British scientist Alfred Newton gave the parrot its own genus, Lophopsittacus. This name means "crested parrot" in Ancient Greek. More fossils were found later, including leg bones and a breastbone.

In 1973, a small fossil parrot from Mauritius was thought to be related. It was named Lophopsittacus bensoni. But in 2007, scientist Julian Hume said it was a different species. He called it Thirioux's grey parrot. Hume also found a second skull of the broad-billed parrot.

How the Parrot Evolved

Scientists are still learning about the broad-billed parrot's family tree. Its large jaws and other bone features suggest it might be related to the Rodrigues parrot. Many birds on the Mascarene islands, like the dodo, came from ancestors in South Asia. Scientists think this might be true for the parrots too.

During the Ice Age, sea levels were lower. This made it easier for birds to fly to islands that are now far apart. Fossils show that Mascarene parrots had big heads and jaws. They also had smaller chest bones and strong leg bones. Hume believes they all came from a group called Psittaculini. Parrots from this group have settled on many islands in the Indian Ocean.

What the Parrot Looked Like

The broad-billed parrot had a very large head and beak compared to its body. Its skull was flatter than other Mascarene parrots. It had a clear crest of feathers on its forehead. This crest was firmly attached, so the bird could not move it up or down. Its jaw was also very wide.

A detailed pencil sketch from 1601 shows more features. It shows the crest as a tuft of rounded feathers. It also shows rounded wings with long feathers and a slightly forked tail. The two middle tail feathers were longer than the others.

Fossil bones show that males were larger than females. Males were about 55–65 cm (22–26 inches) tall. Females were about 45–55 cm (18–22 inches) tall. This size difference between males and females was the biggest among all parrots. The two birds in the 1601 sketch might show this difference.

Possible Colors

The exact colors of the broad-billed parrot have been a bit confusing. The 1601 report said the bird had "two or three colours." The last description, from 1673–75, was by a German preacher named Johann Christian Hoffman. He wrote:

There are also geese, flamingos, three species of pigeon of varied colours, mottled and green perroquets, red crows with recurved beaks and with blue heads, which fly with difficulty and have received from the Dutch the name of Indian crow.

Some scientists thought the bird was all blue-grey. But in 2003, Julian Hume looked closely at the old journal. He suggested the head was blue and the beak might have been red. The rest of the body could have been grey or blackish.

In 2015, a new translation of an old report was published. A Dutch soldier described the bird as "very beautifully coloured." Hume then thought the bird might have been brightly colored. He suggested it had a red body, blue head, and red beak. The feathers might have even looked different colors depending on the light.

Behavior and Life

A Dutch soldier named Johannes Pretorius kept some Mauritian birds in captivity. He described the broad-billed parrot's behavior:

The Indian ravens are very beautifully coloured. They cannot fly and are not often found. This kind is a very bad tempered bird. When captive it refuses to eat. It would prefer to die rather than to live in captivity.

Even though it might have fed on the ground, its leg bones suggest it also lived in trees. Some early scientists thought it couldn't fly because of its short wings in the 1601 sketch. But the original pencil sketch shows the wings were not that short. They were broad, which is common for birds living in forests. Also, Hoffman's account says it could fly, though with difficulty. The first drawing shows it on top of a tree, which a flightless bird couldn't do. So, it was probably a weak flier, but not completely flightless.

The difference in beak size between males and females might mean they ate different foods. Or it might mean they had special roles in nesting. The large difference in head size might also have affected how each sex lived.

Some thought the parrot was active at night, like the kākāpō. But old records don't support this. Its eye sockets were similar to other large parrots active during the day. The parrot was found in dry areas near the coast. This was where people could easily reach. It might have nested in tree holes or rocks. The name "raven" or "crow" might have come from its loud call or dark feathers.

Many other animals on Mauritius became extinct after humans arrived. The island's forests were mostly cut down. The broad-billed parrot lived with other now-extinct birds. These included the dodo, the red rail, and the Mauritius blue pigeon. Many reptiles also disappeared, like giant tortoises.

What the Parrot Ate

The broad-billed parrot's large beak was like that of the hyacinth macaw. Hyacinth macaws eat very hard palm nuts. Many palm trees on Mauritius have hard seeds. The broad-billed parrot likely ate these, including seeds from Latania loddigesii and Sideroxylon grandiflorum.

Some scientists first thought its jaw was weak and it ate soft fruits. But later studies showed its jaw was strong, like the hyacinth macaw's. This means it could easily crack open hard nuts.

Scientists also think the broad-billed parrot helped spread seeds. Like the dodo, it could only reach seeds on the ground. It likely ate the largest seeds and helped them grow in new places.

Why the Parrot Disappeared

Mauritius was visited by Arabs and Portuguese sailors long ago. But they did not settle there. The Dutch took over the island in 1598. They used it to resupply their trade ships. The Dutch sailors were mostly interested in the animals for food.

Of the about eight parrot species unique to the Mascarene islands, only the echo parakeet on Mauritius is still alive. The others likely died out due to too much hunting and cutting down forests.

Because it flew poorly and was large, the broad-billed parrot was easy prey for sailors. Its nests were also vulnerable to new animals like crab-eating macaques and rats. The parrot was known to be aggressive. This might be why it survived for a while against these new threats.

The broad-billed parrot likely became extinct by the 1680s. This was when the palm trees it might have eaten were cut down a lot. Unlike other parrots, there are no records of broad-billed parrots being taken as pets. This might be because people thought of them as "ravens." Also, they might not have survived the journey if they only ate certain seeds. Some scientists believe hunting was not the main reason. They think that even a small amount of deforestation could have harmed them.

Images for kids

-

Statues in Hungary of Newton's parakeet and the broad-billed parrot

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |