Piping plover facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Piping plover |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Sauble Beach, Ontario, Canada | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Charadriidae |

| Genus: | Charadrius |

| Species: |

C. melodus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Charadrius melodus (Ord, 1824)

|

|

| Subspecies | |

|

|

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The piping plover (Charadrius melodus) is a small shorebird. It is about the size of a sparrow and has a sand-colored body. These birds build their nests and find food along sandy and gravel beaches in North America.

Adult piping plovers have yellow-orange-red legs. They have a black band across their forehead, from one eye to the other. There is also a black stripe across their chest. This chest band is usually thicker in males during breeding season. This is the only way to tell male and female plovers apart.

Piping plovers are hard to spot when they stand still. Their sandy color helps them blend in with the beach. They usually run in short bursts and then stop.

There are two types, or subspecies, of piping plovers. The eastern group is called Charadrius melodus melodus. The mid-west group is called C. m. circumcinctus. The bird's name comes from its soft, bell-like whistles. You can often hear these calls before you see the bird.

About 6,510 piping plovers are estimated to be alive today. In 2003, about 3,350 birds lived on the Atlantic Coast. This was more than half of the total population. The number of piping plovers has been growing since 1999.

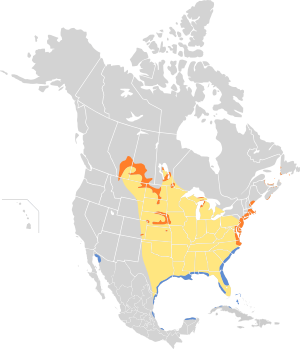

Piping plovers breed on beaches and sand flats. These areas are found along the Atlantic Ocean coast and the shores of the Great Lakes. They also live in the mid-west of Canada and the United States. They build their nests on sandy or gravel beaches.

These shorebirds look for food on beaches, mostly by sight. They move across the sand in short, quick runs. Piping plovers usually search for food near the high tide line and close to the water's edge. They mainly eat insects, marine worms, and crustaceans.

Contents

About the Piping Plover

The American naturalist George Ord first described the piping plover in 1824. There are two recognized subspecies. One is C. m. melodus from the Atlantic Coast. The other is C. m. circumcinctus from the Great Plains. The circumcinctus subspecies is usually darker. It has more noticeable dark cheeks and face markings. Breeding male circumcinctuses often have more black on their forehead and bill. They also tend to have complete chest bands.

What Does a Piping Plover Look Like?

The piping plover is a strong bird with a large, round head. It has a short, thick neck and a small bill. It is a sand-colored, dull gray or khaki shorebird. Adult birds have yellow-orange legs. During breeding season, they have a black band across their forehead. They also have a black ring around their neck. These black bands fade during the non-breeding season. Their bill is orange with a black tip.

Piping plovers are about 15 to 19 centimeters (6 to 7.5 inches) long. Their wingspan is about 35 to 41 centimeters (14 to 16 inches). They weigh between 42 and 64 grams (1.5 to 2.3 ounces).

Piping Plover Calls

The piping plover makes a soft, whistled peep peep sound. You can hear this call from birds standing or flying. Their alarm call is a soft pee-werp. The second part of this call is lower in pitch.

Where Piping Plovers Live

Piping plovers spend most of their lives on open sandy beaches or rocky shores. They often stay in high, dry areas away from the water. You can find them on the Atlantic Ocean coast of the U.S. and Canada. They also live on the shores of the Great Lakes.

They build their nests higher on the shore, near beach grass and other objects. It is very rare to see a piping plover anywhere else. During winter, many piping plovers migrate south to The Bahamas. They have also been seen in Cuba and other parts of the West Indies. Some have even been recorded in Ecuador and Venezuela.

Piping plovers migrate from their northern homes in the summer. They fly south for the winter months. Their winter homes include the Gulf of Mexico, the southern Atlantic coast of the United States, and the Caribbean. They start flying north in mid-March. Their breeding areas stretch from southern Newfoundland and Labrador down to northern South Carolina.

Migration south begins in August for some adults and young birds. By mid-September, most piping plovers have flown south for winter.

Piping Plover Behavior and Reproduction

Piping plovers usually arrive at sandy beaches to breed in mid to late April.

Breeding and Nests

Males start claiming territories and finding mates in late March. Once a pair forms, the male digs several small dips in the sand. These are called scrapes, which are like early nests. He digs these along the high shore near the beach grass. Males also do special dances and flights to attract females. This includes tossing small stones and diving in the air.

Scrapes are often found in the same areas where least terns build their nests. Females will check out the scrapes. They choose a good one and decorate it with shells and other small pieces. This helps to camouflage the nest. If a female likes a scrape, she will allow the male to mate with her. The male performs a mating ritual. He stands tall, puffs himself up, and quickly stomps his legs. If the female finds the scrape good enough, she lets the male stand on her back. Mating happens within a few minutes.

Most first nests each season have four eggs. These eggs can appear as early as mid to late April. Females lay one egg every other day. Later nests, like second or third attempts, might only have two or three eggs. Both the male and female share the job of sitting on the nest. This is called incubation. Incubation usually lasts 27 days. All the eggs typically hatch on the same day.

After the chicks hatch, they can find food within hours. The adult plovers then protect them from the weather by brooding them. They also warn the chicks about any danger. Like many other plovers, adult piping plovers sometimes pretend to have a "broken wing display". This draws attention to themselves and away from the chicks if a predator is nearby. This display is also used during nesting to distract predators from the eggs.

A main way chicks protect themselves is by blending in with the sand. It takes about 30 days for chicks to learn to fly. They must be able to fly at least 50 meters (50 yards) to be considered fledglings.

To protect nests from predators, many conservation groups use special fences. These are like round wire cages with screened tops. They let adult birds in and out but keep predators away from the eggs. After chicks hatch, some areas put up snow fences. These fences stop cars and pets from going into certain areas. This helps keep the chicks safe.

Threats to nests include crows, cats, raccoons, and foxes. Sometimes, these fences are not used. This is because they can sometimes draw more attention to the nest. Natural dangers to eggs or chicks include storms, strong winds, and very high tides. People disturbing nests can also cause birds to leave their eggs or chicks. It is best to stay away from any bird that seems upset. This helps prevent any unintended consequences.

Piping Plover Status and Conservation

The piping plover is a globally threatened and endangered bird. It is not common in many parts of its range. The United States has listed it as "endangered" in the Great Lakes region. It is listed as "threatened" in other breeding areas. While it is federally threatened, some states list it as endangered. These states include Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New York, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. The Parker River Refuge in Massachusetts helps protect piping plovers. It has the second largest plover population on the North Shore.

In eastern Canada, piping plovers are only found on coastal beaches. In 1985, Canada declared it an endangered species. A large group of plovers in Ontario disappeared completely. However, in 2008, piping plover nests were found at Wasaga Beach and near Sauble Beach, Ontario. These were along the Ontario Great Lakes shores. There is also some proof of nesting at other places in Ontario, like Port Elgin, Ontario in 2014.

In the 1800s and early 1900s, piping plovers were hunted for their feathers. These feathers were used to decorate women's hats. This practice caused their population to drop. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 helped the population recover by the 1930s.

The second decline in piping plover numbers happened after World War II. This was due to more buildings, efforts to protect shorelines, and loss of habitat. Human activity near nesting sites also played a role. The Great Lakes populations eventually became very small, with only about two dozen birds. On the Missouri River sandbars, the number of breeding birds changed. The population grew from 2012 to 2017 after new habitats were created.

Important nesting areas are now being protected. This helps the population during its breeding season. The number of piping plovers has increased since protection programs began. However, the species is still in serious danger.

Current efforts to help piping plovers include:

- Finding and protecting known nesting sites.

- Teaching the public about the birds.

- Limiting or stopping people and vehicles near nests and chicks.

- Controlling pets like cats and dogs that might harm birds or eggs.

- Removing predators like foxes, raccoons, and skunks.

In coastal areas like Plymouth, Cape Cod, Long Island, Sandy Hook, Cape Henlopen State Park in Delaware, North Manitou Island in Lake Michigan, and Cape Hatteras National Seashore in North Carolina, beach access is sometimes limited. This is done to protect piping plovers and their chicks during important breeding times.

In 2019, the first known pair of piping plovers nested in Chicago at Montrose Beach. Three chicks hatched in July. These were the first chicks in Cook County in 60 years. A music festival was planned for August, which could have threatened the nest. In July 2019, the festival was canceled. The same pair of plovers returned in 2020, and their first chick hatched in June 2020.

Piping Plovers and Climate Change

Piping plovers live on shores, so they might be greatly affected by climate change. This is because climate change impacts both their water and land homes.

Rising Water Levels in Inland Habitats

A key area for piping plovers is the Prairie Pothole Region. This region is in South Dakota, North Dakota, and Canada. The shallow wetlands here have changing water levels. Piping plovers that breed in this region need low water levels. This reveals the shorelines they use for nesting.

Climate change is causing wetlands to become fuller. This reduces the shoreline nesting areas. Research on 32 piping plover wetland habitats showed that higher water levels meant fewer plovers. This suggests that a warmer climate and more rain will harm piping plover breeding areas in the Prairie Pothole Region.

Sea Level Rise in Coastal Habitats

Climate change is also causing sea level rise. This can affect the piping plover's other main home, the Atlantic Coast of the U.S. and Canada. Studies have looked at how sea level rise threatens plover habitats on barrier islands in Long Island, New York. They found that rising sea levels will shrink piping plover breeding areas.

Breeding habitats could move inland. However, they would still be smaller due to human development. This might lead to disagreements between protecting plover habitats and human recreation. This is because sea level rise will make habitats take up a larger part of the islands. Research also shows that a large hurricane with higher sea levels could flood up to 95% of plover habitat. So, more coastal storms due to climate change, plus rising sea levels, could be very damaging.

Similar research has been done on the Florida coastline. This is part of the piping plovers’ Atlantic coast habitat. It looked at how sensitive the habitat is to sea level rise. Florida's coastal species are especially at risk from climate change. This is due to sea level rise and more tropical storms. Piping plovers rely on this habitat. They migrate south from their breeding grounds to spend about three months in Florida during winter. It is thought that 16% of coastal landforms will be lost by the year 2100 due to flooding. Also, sea level rise might make the coastline more complex. This could lead to more habitat fragmentation. So, changes to Florida's coastline will likely affect piping plover ecology. Research also shows that piping plovers are at high risk of decline among shorebirds affected by these changes.

Warmer Sand Temperatures

Hotter temperatures from climate change may also directly affect piping plovers. Piping plovers nest on the ground in open areas. This means their nests are exposed to high temperatures. Because of these high temperatures, piping plovers have special ways to keep their eggs and themselves cool. This is called thermal regulation.

Research looked at how sand temperature affects piping plover nesting in North Dakota. This study was done during the 2014-2015 breeding seasons. As sand temperatures went up, plovers spent less time on their nests. They also spent more time shading their nests. Climate change will likely increase sand temperatures. This will affect how piping plovers nest on the ground.

Images for kids

-

Area closed within Cape Henlopen State Park, Delaware, where piping plovers are known to nest

See also

In Spanish: Frailecillo silbador para niños

In Spanish: Frailecillo silbador para niños