Battle of Bladensburg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Bladensburg |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

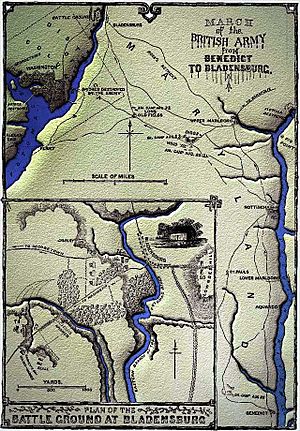

British march from Benedict to Bladensburg, 19 August 1814, by Benson Lossing |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,500 60 rockets |

6,920 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 64 killed 185 wounded |

10–26 killed 40–51 wounded 100–120 captured |

||||||

The Battle of Bladensburg was a major fight during the War of 1812. It happened on August 24, 1814, near Bladensburg, Maryland, not far from Washington, D.C. This battle is often called "the greatest disgrace" for American forces.

In this battle, British soldiers and Royal Marines easily defeated a combined force of U.S. Army regulars and state militia. The American loss led to the capture and burning of Washington, D.C. This was the only time since the American Revolutionary War that the U.S. capital was taken by a foreign army.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

British Plans for Attack

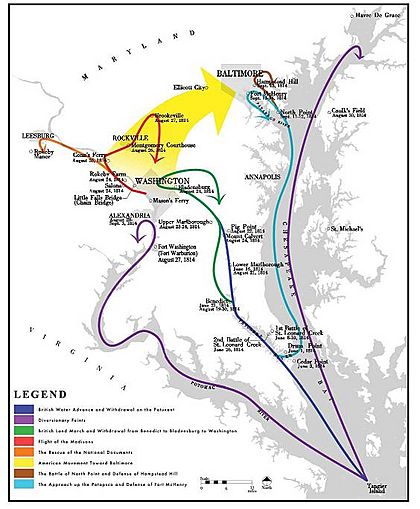

For the first two years of the War of 1812 (1812–1815), Britain was busy fighting Napoleon in Europe. But British warships, led by Rear Admiral George Cockburn, controlled the Chesapeake Bay. They captured many U.S. trading ships and raided small towns.

By April 1814, Napoleon was defeated. This meant Britain could send many more ships and soldiers to fight in America. Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane took charge of the British forces in North America. He wanted to attack the United States more aggressively.

Most new British troops went to Canada. But a special group of 2,500 soldiers, led by Major General Robert Ross, sailed to Bermuda. Their goal was to raid the U.S. East Coast. This would help the British army defending Canada.

U.S. Prepares for Defense

President James Madison learned that Britain was sending more troops. On July 1, 1814, he met with his advisors. The Secretary of War, John Armstrong Jr., thought the British would not attack Washington. He believed Baltimore was a more likely target because it had more valuable goods.

Despite this, President Madison put Brigadier General William H. Winder in charge of the area around Washington and Baltimore. Winder had been captured in a battle a year earlier. He spent a month visiting forts but did not build strong defenses. He also didn't order any militia (citizen soldiers) to prepare early.

The Campaign Begins

British Advance on Washington

Major General Ross commanded the British troops in the Chesapeake Bay. Vice Admiral Cochrane decided where to attack. He wanted a quick strike on Washington. Ross's soldiers had been on ships for months and lacked cavalry or heavy equipment.

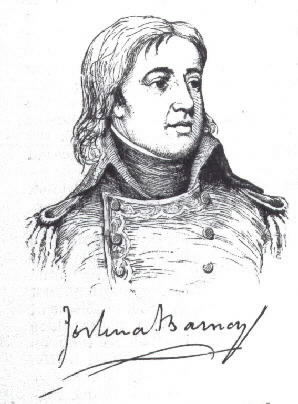

Ross's first goal was to destroy the U.S. Chesapeake Bay Flotilla, a group of small U.S. Navy ships. British forces landed at Benedict, Maryland, on August 19. They marched up the Patuxent River. Commodore Joshua Barney, who led the U.S. flotilla, had to destroy his own ships to keep them from being captured. He then marched his men toward Washington.

From Upper Marlboro, Maryland, Ross could attack either Washington or Baltimore. This confused the Americans. On the night of August 23–24, Ross decided to attack Washington. He had about 4,370 men. This included infantry, Royal Marines, and about 200 Colonial Marines (black soldiers who were formerly enslaved people). He also had some cannons and rockets.

Ross had two paths to Washington. He chose the eastern route through Bladensburg. On the morning of August 24, he made a fake move on the southern route. Then, he quickly turned north toward Bladensburg.

U.S. Forces Prepare for Battle

In Washington, General Winder had about 1,000 regular soldiers and around 7,000 militia. The militia were not well-trained or equipped. On August 20, Winder ordered his troops to move south to meet the British. After a small fight on August 22, Winder ordered a quick retreat.

Winder knew that Bladensburg was key to defending Washington. It controlled roads for reinforcements. It was also one of the easiest ways for the British to reach the capital. On August 20, Winder told Brigadier General Tobias Stansbury to take the best position near Bladensburg.

Stansbury set up his forces on Lowndes Hill. He quickly dug earthworks for his cannons. But on August 23, Winder ordered him to move his tired troops across the Bladensburg bridge. Stansbury did not burn the bridge, which was a big mistake. This gave up a strong defensive position.

Meanwhile, in Washington, government offices were quickly packing up records. They sent them away to Maryland or Virginia to keep them safe.

The Battle Unfolds

General Winder had about 7,000 men at Bladensburg. Most were militia from Maryland, Virginia, and the District of Columbia. Stansbury's Maryland militia were placed too far from the river to stop the British from crossing.

Around noon on August 24, the British army reached Bladensburg. The British light infantry, led by Colonel William Thornton, rushed across the bridge. American artillery and riflemen stopped their first attack. But the British eventually crossed the river.

As the British advanced, some American militia broke and ran away. General Winder gave confusing orders. The 5th Maryland militia fought bravely but were forced to retreat.

The British then faced General Walter Smith's brigade and Commodore Barney's cannons. Barney's men, with heavy cannons from the Washington Navy Yard, were positioned along the road to Washington. Thornton's light infantry attacked several times but were pushed back by Barney's artillery. Thornton was badly wounded.

However, the British began to surround Smith's left side. Winder ordered Smith's brigade to retreat. Barney's 300 sailors and 103 Marines kept fighting bravely. They held off the British attacks with cannons and hand-to-hand combat. But when their ammunition ran low, Barney ordered his men to retreat. Barney himself was wounded and captured. The British praised his bravery and later released him.

Most of the American militia fled the battlefield. They ran through the streets of Washington, D.C. President Madison and other government officials were at the battle and barely escaped capture. They also fled the capital.

Journalist Steve Vogel praised British commander Robert Ross. He said Ross used clever tricks to confuse the Americans. This stopped them from defending Bladensburg well.

After the Battle

The American retreat was so fast and messy that the battle became known as the "Bladensburg Races." It was called "the greatest disgrace ever dealt to American arms."

That same night, the British entered Washington without a fight. They set fire to many government buildings, including the White House and the Capitol. This event is known as the Burning of Washington. The British commander, Vice Admiral Cochrane, wanted to get revenge for American troops burning a Canadian town earlier.

Major General Ross, the British commander, was killed in a later battle. His family later changed their name to Ross-of-Bladensburg to remember his victory.

Today, some U.S. Army National Guard units carry on the history of the American regiments that fought at Bladensburg. In the British Army, several regiments were given the "Bladensburg" battle honor for their bravery.

Black Soldiers in the Battle

Black sailors fought with Commodore Joshua Barney's American naval force at Bladensburg. They provided important cannon support. Charles Ball, a black sailor, wrote in his memoir that his unit fought until Commodore Barney was shot. He said the militia ran, but his men did not.

Historians believe that 15% to 20% of American naval forces in the War of 1812 were black. Commodore Barney was asked if his black sailors would run. He replied, "No Sir... they don't know how to run; they will die by their guns first." He was right. Young sailor Harry Jones, a free black man, was wounded at Bladensburg and treated at the Naval Hospital.

Black troops also fought for the British. They were part of the Corps of Colonial Marines. These were formerly enslaved black Americans who were promised freedom by the British. They received the same training and pay as other Royal Marines. After the war, the British kept their promise and moved these soldiers and their families to Canada and Bermuda.

Battlefield Today

It's hard to preserve the entire Bladensburg battlefield today because of city growth. But the town of Bladensburg and Prince George's County have put up historical markers. They offer a walking tour with an audio guide to help people explore the battle site.