Billy Mitchell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Billy Mitchell

|

|

|---|---|

Then-Brigadier General William L. Mitchell

|

|

| Birth name | William Lendrum Mitchell |

| Born | December 29, 1879 Nice, France |

| Died | February 19, 1936 (aged 56) New York City, United States |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1898–1926 |

| Rank | Colonel (Permanent) Brigadier General (Temporary) |

| Commands held | Air Service, Third Army – AEF |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross Distinguished Service Medal World War I Victory Medal Congressional Gold Medal (posthumous) |

William Lendrum Mitchell (December 29, 1879 – February 19, 1936) was a United States Army officer. Many people consider him the "father of the United States Air Force" because of his strong belief in air power.

Mitchell served in France during World War I, leading all American air combat units there. After the war, he became a top leader in the Air Service. He strongly believed that airplanes would be super important in future wars. He especially argued that bombers could sink even the biggest battleships. To prove his point, he organized bombing tests against old ships.

His strong opinions and criticisms often upset other Army leaders. In 1925, he was put on trial by the military (a court-martial) for speaking out too much. He had accused Army and Navy leaders of making bad decisions about national defense by focusing on warships instead of air power. He later left the military.

After his death, Mitchell received many honors, including a special Congressional Gold Medal. He was also the first person to have an American military aircraft named after him, the North American B-25 Mitchell bomber. The Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport in Wisconsin is also named in his honor.

Contents

Early Life and Early Army Days

William Mitchell was born in Nice, France, in 1879. His father, John L. Mitchell, was a rich Wisconsin senator. William grew up on a large estate near Milwaukee.

He started at Columbian University but left to join the United States Army during the Spanish–American War in 1898. He quickly became an officer in the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

From 1900 to 1904, Mitchell worked in Alaska. He helped build a telegraph system to connect isolated Army posts and gold rush camps. As early as 1906, he predicted that future wars would be fought in the air. In 1908, he watched Orville Wright fly and later took flying lessons himself.

In 1912, Mitchell became one of the youngest officers on the Army's General Staff. He was temporarily put in charge of the Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps, which was an early version of the Air Force. He even took private flying lessons to learn more, paying for them himself. By July 1916, he was promoted to major and became Chief of the Air Service of the First Army.

Air Power in World War I

When the United States entered World War I in April 1917, Mitchell was in France. He quickly set up an office and worked closely with British and French air leaders. He studied their strategies and aircraft. On April 24, he became the first American officer to fly over German lines.

Mitchell quickly became known as a brave and energetic leader. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and then to colonel. In September 1918, he planned and led almost 1,500 British, French, and Italian aircraft in the air part of the Battle of Saint-Mihiel. This was one of the first times air and ground forces worked together in such a big way. He was promoted to temporary brigadier general and commanded all American air combat units in France.

He finished the war as a top American airman, earning several awards like the Distinguished Service Cross. However, his strong opinions sometimes caused problems with his superiors.

Fighting for Air Power

When Mitchell returned to the United States in 1919, he expected to lead the Air Service. Instead, a different general was appointed. Mitchell believed that World War I would not be the "war to end all wars." He said, "If a nation ambitious for universal conquest gets off to a flying start in a war of the future, it may be able to control the whole world."

He strongly believed that air power would soon be the most important part of warfare. He argued that the Air Force should be its own independent branch, equal to the Army and Navy. He found support from some members of Congress who also wanted a separate Department of Aeronautics.

Mitchell thought that floating bases were important for defending against naval threats. However, Navy leaders did not agree with him. Mitchell met with Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and other admirals. Mitchell said that the Navy's surface ships were becoming outdated and that the Air Service could develop bombs to sink battleships. His ideas were not well received.

Mitchell's relationship with his superiors got worse as he criticized both the War and Navy departments. He felt they weren't thinking enough about air power's future. He pushed for new aircraft ideas like better bomb-sights and engine superchargers. He also encouraged using planes to fight forest fires and patrol borders. He wanted anything that would help aviation grow and keep it in the news.

The Bombing Tests: Airplanes vs. Battleships

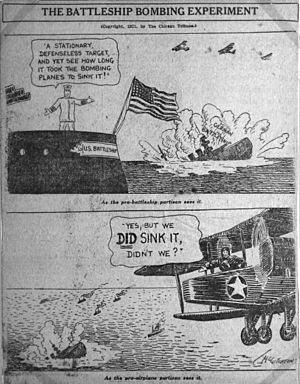

In 1921, Mitchell pushed for joint Army-Navy exercises to test his ideas. These tests, called Project B, would use old or captured ships as targets. Mitchell believed that building expensive battleships was taking money away from military aviation. He argued that a thousand bombers could be built for the cost of one battleship, and those bombers could sink that battleship.

The Navy was hesitant but agreed to the tests. They had already tried to sink an old battleship, the Indiana, with their own planes. But it was revealed that they used dummy bombs and then explosives placed on the ship to sink it. This made Congress demand new, proper tests.

Mitchell gathered 125 aircraft and 1,000 men at Langley Field for the tests. He trained them in anti-ship bombing. A Russian pilot, Alexander Seversky, suggested aiming bombs near the ships. He explained that the water pressure from underwater blasts would damage the hull more than direct hits.

Rules of the Tests

The Navy set strict rules for the tests, which Mitchell felt made it harder to sink the ships. For example, ships had to be sunk in deep water far from shore, making it difficult for the bombers. Planes were not allowed to use torpedoes, and they had to stop between hits for damage checks.

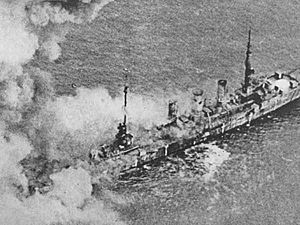

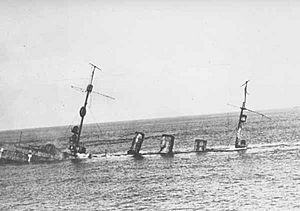

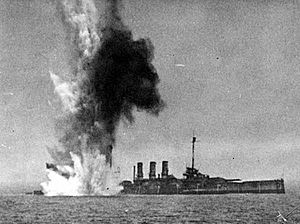

Despite the rules, Mitchell's team successfully sank the ex-German destroyer G-102 and the ex-German light cruiser Frankfurt in June and July 1921. Fighters would first attack to simulate suppressing anti-aircraft fire, then bombers would follow with high-explosive bombs. Mitchell watched from his own plane, The Osprey.

Sinking the Ostfriesland

On July 20, 1921, the Navy brought out the ex-German World War I battleship, Ostfriesland. After initial smaller bomb attacks, the ship was taking on water. The Navy delayed further bombing, but Mitchell's bombers were eventually allowed to continue.

On July 21, Mitchell's bombers dropped six 2,000 lb (910 kg) bombs near the Ostfriesland. Mitchell described how the ship rose "eight to ten feet" from the underwater blasts. There were no direct hits, but the close-by bombs ripped open the hull. The ship sank in just 22 minutes.

Mitchell used this sinking to show the power of air attacks. Even though the tests were not exactly like "war-time conditions," the fact that a battleship was sunk by planes was a huge deal. Mitchell repeated these successful tests on other battleships in 1921 and 1923. These tests forced the Navy to take naval air power more seriously.

What Happened After the Tests?

The bombing tests caused a lot of excitement and controversy. The Navy and President Harding were upset because it made the Navy look weak. They tried to downplay Mitchell's results, but his report was leaked to the press.

Mitchell continued to speak out, criticizing Army and Navy leaders. In March 1925, his term as Assistant Chief of the Air Service ended. He was sent to San Antonio, Texas, as an air officer to a ground forces unit. This was widely seen as a punishment for his outspokenness.

Why Was He Court-Martialed?

In September 1925, a Navy airship, the Shenandoah, crashed in a storm, killing 14 crew members. Mitchell publicly accused senior leaders in the Army and Navy of being incompetent and making "almost treasonable" decisions about national defense.

Because of these strong statements, President Calvin Coolidge ordered that Mitchell be put on trial by a military court, known as a court-martial. The trial began in November 1925 and lasted seven weeks. Mitchell's lawyers argued that he had a right to speak freely. Many famous people, including Eddie Rickenbacker and Douglas MacArthur, testified or were involved in the trial.

The court found Mitchell guilty of insubordination. He was suspended from active duty for five years without pay, though President Coolidge later changed it to half-pay. The court said they were lenient because of Mitchell's good service during World War I. Mitchell chose to resign from the Army on February 1, 1926.

Later Life and Death

After leaving the military, Mitchell spent the next decade writing and speaking about air power. He tried to convince everyone that air power was the future of defense. He even met with Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932, who was interested in his ideas for a unified Department of Defense.

Mitchell died on February 19, 1936, in New York City at the age of 56. He was buried in Forest Home Cemetery in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

His Legacy Lives On

Mitchell's ideas about air power proved to be true after his death. During World War II, many warships were sunk by air attacks, just as he had predicted. While many of these sinkings were by planes from aircraft carriers, not just land-based bombers, it showed that navies had learned from Mitchell's demonstrations.

Mitchell has received many honors:

- In 1941, the North American B-25 Mitchell bomber was named after him. This plane was famously used in the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo in 1942.

- Also in 1941, the main airport in his hometown of Milwaukee was renamed Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport.

- In 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt asked Congress to give Mitchell the Congressional Gold Medal for his "outstanding pioneer service and foresight in the field of American military aviation." It was awarded in 1946.

- In 1943, Walt Disney made a film called "Victory Through Air Power" which was dedicated to Mitchell and explained his ideas about air power.

- In 1955, a movie called The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell, starring Gary Cooper, told his story.

- Mitchell was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1966.

- Mount Billy Mitchell in Alaska was named after him in 1968.

- The cadet dining hall at the United States Air Force Academy is named Mitchell Hall.

- The Civil Air Patrol has an award for cadets called the General Billy Mitchell Award.

- In 1999, Mitchell's portrait was put on a U.S. postage stamp.

- In 2007, the Air Force created the Air Force Combat Action Medal, based on the design painted on Mitchell's own aircraft from World War I.

Military and Civilian Awards

Mitchell received many awards for his service:

|

Civilian AwardsImages for kidsSee also

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |

In Spanish:

In Spanish: