Carter G. Woodson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

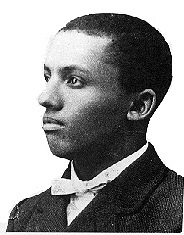

Carter Godwin Woodson

|

|

|---|---|

Carter G. Woodson

|

|

| Born | December 19, 1875 |

| Died | April 3, 1950 (aged 74) Washington, DC

|

| Education | B.Litt, Berea College (1903) A.B.; M.A., University of Chicago (1908) PhD, Harvard University (1912) |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Known for | Founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (now called Association for the Study of African American Life and History). Established Negro History Week. |

Carter Godwin Woodson (December 19, 1875 – April 3, 1950) was an important African-American historian and writer. He is known for starting the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. Woodson was one of the first experts to deeply study African-American history. He also helped create The Journal of Negro History in 1915. Many people call him the "father of black history." In February 1926, he began "Negro History Week," which later became Black History Month.

Contents

Carter Woodson's Early Life and Education

Carter G. Woodson was born in Buckingham County, Virginia, on December 19, 1875. His parents, James and Eliza Riddle Woodson, were formerly enslaved people. His father helped Union soldiers during the Civil War. The family moved to West Virginia because a high school for Black students was being built in Huntington.

Carter came from a large, poor family. This meant he could not go to school regularly. But he taught himself many basic school subjects by the time he was 17. Wanting more education, Carter went to Fayette County. He worked as a miner in the coal fields to earn money. He could only attend school for a few months each year.

In 1895, at age 20, Woodson entered Douglass High School. He finished his diploma in less than two years. From 1897 to 1900, Woodson taught in Winona. In 1900, he became the principal of Douglass High School. He earned his Bachelor of Literature degree from Berea College in Kentucky in 1903. He took classes part-time while working.

Woodson's Career in Education

From 1903 to 1907, Woodson worked as a school supervisor in the Philippines. Later, he studied at the University of Chicago. He earned two degrees there in 1908. He was also a member of the first Black professional fraternity, Sigma Pi Phi.

He earned his PhD in history from Harvard University in 1912. He was the second African American to get a doctorate from Harvard. His doctoral paper was about Virginia's history. He did research for it at the Library of Congress. After getting his PhD, he kept teaching in public schools. Later, he became a professor at Howard University. He even served as the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences there.

Woodson believed that the history of African Americans was often ignored. He felt it was also sometimes shown incorrectly by scholars. He saw a need to research the forgotten past of African Americans. In 1915, he published a book called The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861. He wrote it with Alexander L. Jackson.

Carter G. Woodson often stayed at the Wabash Avenue YMCA when he visited Chicago. His experiences there inspired him to create the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915. This group held conferences and published The Journal of Negro History. It especially aimed to help those who taught Black children.

Woodson thought that education could help reduce racism. He also believed that more contact between Black and white people could help. He promoted the organized study of African-American history for this reason. Woodson later started the first Negro History Week in Washington, D.C., in 1926. This event was the beginning of Black History Month.

He also served as Academic Dean of the West Virginia Collegiate Institute from 1920 to 1922.

Besides his first book, he wrote A Century of Negro Migration. This book is still published by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). He studied many parts of African-American history. For example, in 1924, he published the first study of free Black slaveowners in the United States.

Woodson once wrote about the power of ideas: "If you can control a person’s thinking, you don’t have to worry about their actions. If you can make someone believe they are not as good, they will act that way without being told."

Woodson and the NAACP

Woodson was connected with the Washington, D.C. branch of the NAACP. Its chairman was Archibald Grimké. On January 28, 1915, Woodson wrote to Grimké. He shared his ideas for the group.

Woodson suggested two things. First, the branch should get an office. This office would be a place where Black people could report their concerns. It would also help the NAACP reach more parts of the city. Second, he suggested hiring someone to find new members and get subscriptions for The Crisis. This was the NAACP magazine edited by W. E. B. Du Bois.

W. E. B. Du Bois added another idea. He suggested avoiding businesses that did not treat all races fairly. Woodson said he would help with these efforts. He even offered to pay the office rent for one month. However, Grimké did not like Woodson's ideas.

On March 18, 1915, Woodson wrote back to Grimké. He said: "I am not afraid of being sued by white businessmen. It would help our cause. Let us not be afraid. We have been in this state for three centuries. I am ready to act, if I can find brave people to help me."

Woodson and Grimké had different ideas about how the NAACP should act. Grimké wanted a more careful approach. This difference led Woodson to end his connection with the NAACP.

Creating Black History Month

Woodson spent the rest of his life studying history. He worked hard to save the history of African Americans. He collected thousands of old items and books. He noticed that contributions by African Americans were "overlooked, ignored, and even hidden" in history textbooks. He believed that prejudice against Black people came from the idea that they had not contributed to human progress.

In 1926, Woodson started "Negro History Week." He chose the second week in February. This week included the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. This week of recognition became popular. Later, it was expanded to the full month of February. Now, it is known as Black History Month.

Woodson's Colleagues and Influence

Woodson believed in self-reliance and respect for one's race. These were values he shared with Marcus Garvey. Garvey was an activist from Jamaica who worked in New York. Woodson became a regular writer for Garvey's weekly newspaper, Negro World.

Woodson's work put him in touch with many Black thinkers and activists. He wrote to people like W. E. B. Du Bois, John E. Bruce, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, and Hubert H. Harrison. Even with all his work for the Association, Woodson found time to write books. These included The History of the Negro Church (1922) and The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933). These books are still widely read today.

Woodson was not afraid to discuss difficult topics. He used his writings to join important discussions. One topic was the relationship between West Indian and African-American people. Woodson believed that West Indian societies had done better at educating and freeing their people. He supported efforts by West Indians to include Black history and culture in their school lessons.

Some people at the time did not agree with Woodson. They thought it was wrong to teach African-American history separately from general American history. They believed that Black people were simply Americans, with no history apart from others. So, Woodson's efforts to get Black culture and history into schools were often difficult. Today, African-American studies are special fields of study. There is also more focus on how African Americans have contributed to American culture. The United States government now celebrates Black History Month.

Carter Woodson's Lasting Legacy

Carter G. Woodson died suddenly from a heart attack on April 3, 1950. He was 74 years old. He passed away in his office at his home in Washington, D.C. He is buried in Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Suitland, Maryland.

One of Woodson's most visible legacies is that schools now set aside time each year for African-American history. His strong will to make sure Black people were recognized in history inspired many other scholars. Woodson stayed focused on his work his whole life. Many people see him as a person with great vision and understanding. The Association and journal he started in 1915 are still active today. Both have earned great respect in the world of ideas.

Woodson also founded the Associated Publishers in 1920. This is the oldest African-American publishing company in the United States. It helped publish books about Black people that might not have been published otherwise. He created Negro History Week in 1926, which is now Black History Month. He also started the Negro History Bulletin. This was a magazine for elementary and high school teachers. It has been published continuously since 1937. Woodson also helped guide and fund research in African-American history. He wrote many articles and books about Black people. His book The Negro in Our History sold over 90,000 copies by 1966.

Dorothy Porter Wesley said that Woodson would often take his publications to the post office himself. He would then have dinner at the YMCA. He would jokingly turn down dinner invitations, saying, "No, you are trying to marry me off. I am married to my work." Woodson's biggest dream was to complete a six-volume Encyclopedia Africana. This project was not finished when he died.

Honors and Tributes to Carter Woodson

- In 1926, Woodson received the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Spingarn Medal. This is a high honor for African Americans.

- The Carter G. Woodson Book Award was created in 1974. It is given to the best social science books for young readers. These books must show different ethnic groups in the United States.

- The U.S. Postal Service released a stamp honoring Woodson in 1984.

- In 1992, the Library of Congress held an exhibit called "Moving Back Barriers: The Legacy of Carter G. Woodson." Woodson had given his collection of 5,000 items to the Library.

- His home in Washington, D.C., has been saved. It is now called the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included Carter G. Woodson on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

Places Named After Carter G. Woodson

California

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary School in Los Angeles.

- Carter G. Woodson Public Charter School in Fresno.

Florida

- Carter G. Woodson Park, in Oakland Park.

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary School was in Oakland Park. It closed in 1965 when schools were desegregated.

- Dr. Carter G. Woodson African American Museum in St. Petersburg.

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary School in Jacksonville.

- Dr. Carter G. Woodson PK–8 Leadership Academy in Tampa, Florida.

Georgia

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary in Atlanta.

Illinois

- Carter G. Woodson Regional Library in Chicago.

- Carter G. Woodson Middle School in Chicago.

- Carter G. Woodson Library of Malcolm X College in Chicago.

Indiana

- Carter G. Woodson Library in Gary.

Kentucky

- Carter G. Woodson Academy in Lexington.

- Carter G. Woodson Center for Interracial Education, Berea College, in Berea.

Louisiana

- Carter G. Woodson Middle School in New Orleans.

- Carter G. Woodson Liberal Arts Building at Grambling State University, built in 1915, in Grambling.

Maryland

Minnesota

- Woodson Institute for Student Excellence in Minneapolis.

New York

- PS 23 Carter G. Woodson School in Brooklyn.

North Carolina

- Carter G. Woodson Charter School in Winston-Salem.

Texas

Virginia

- The Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

- Carter G. Woodson Middle School in Hopewell.

- C.G. Woodson Road in his home town of New Canton.

- Carter G. Woodson Education Complex in Buckingham County, built in 2012.

Washington, DC

- Carter G. Woodson Junior High School was named for him. It now hosts Friendship Collegiate Academy Public Charter School.

- The Carter G. Woodson Memorial Park is between 9th Street, Q Street and Rhode Island Avenue, NW. The park has a bronze sculpture of the historian.

- The Carter G. Woodson Home, a National Historic Site, is located at 538 9th St., NW, Washington, D.C.

West Virginia

- Carter G. Woodson Jr. High School (renamed McKinley Jr. High School after integration in 1954) in St. Albans, built in 1932.

- Carter G. Woodson Avenue (also known as 9th Avenue) in Huntington. His old school, Douglass High School, is on this avenue.

Images for kids

-

Portrait of Woodson from West Virginia Collegiate Institute's El Ojo yearbook picture (1923)