Paul Cuffe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Captain

Paul Cuffee

|

|

|---|---|

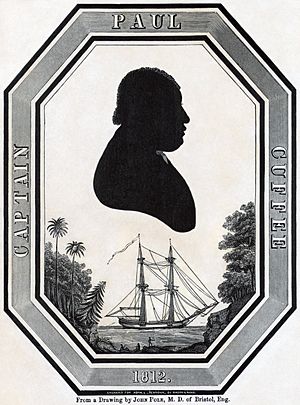

Captain Paul Cuffee engraving, 1812, from a drawing by Dr. John Pole of Bristol, England

|

Paul Cuffe, also known as Paul Cuffee (born January 17, 1759 – died September 7, 1817), was an amazing American businessman, whaler, and abolitionist. He was born free into a multiracial family on Cuttyhunk Island, Massachusetts. Paul Cuffe became a very successful merchant and sea captain. His mother, Ruth Moses, was a Wampanoag woman from Harwich, Cape Cod. His father was an Ashanti man from West Africa who was captured as a child and sold into slavery around 1720. In the 1740s, his father was freed by his Quaker owner. His parents married in 1747 in Dartmouth.

When Paul was 13, his father died. Paul and his older brother, John, took over the family farm. The next year, Paul started working on whaling ships, traveling to the West Indies. During the American Revolutionary War, Paul Cuffe bravely delivered goods to Nantucket by sneaking past a British blockade. After the war, he built a very successful shipping business along the Atlantic Coast and around the world. He even built his own ships in a boatyard. In Westport, Massachusetts, he started the first racially integrated school in the United States.

Paul Cuffe was a very religious Quaker. He joined the Westport Friends Meeting in 1808 and often spoke at services. In 1813, he gave half the money for a new meeting house in Westport and helped build it. This building is still standing today. At that time, few people of color were allowed to join the Friends Meeting.

Cuffe also became involved in a British project to create a colony in Sierra Leone. The British had sent over 1,000 former slaves from America to this colony. These were people who had found freedom with the British during the American Revolution. In 1810, Cuffe sailed to Sierra Leone to see how he could help these settlers. He believed they should produce more goods to sell and develop their own shipping. He traveled to England to share his ideas with British abolitionists, who liked his plans. He made two more trips to Sierra Leone to help make these plans happen.

On his last trip in 1815–16, he took nine free Black families from Massachusetts to Sierra Leone. They went to help the former slaves and local people build their economy. Some historians connect Cuffe's work to the "Back to Africa" idea. This idea was promoted by the American Colonization Society (ACS), which wanted to send free Black people from the U.S. to Africa. The ACS leaders asked for Paul Cuffe's advice. However, many free Black people in Philadelphia and New York City strongly disagreed with the ACS. Because of their objections, Cuffe decided not to support the ACS. He believed his efforts to provide training, tools, and ships would help African people improve their lives and succeed.

Contents

Paul Cuffe's Life Story

Early Years

Paul Cuffe was born on January 17, 1759, on Cuttyhunk Island, Massachusetts. He was the youngest son of Coffe Slocum and Ruth Moses. His father, Kofi, was an Ashanti man from Africa. He was captured when he was about 10 years old and brought to Newport, Rhode Island, as a slave. In 1742, Kofi was sold to John Slocum, a Quaker farmer. John Slocum freed Kofi around 1745.

Kofi took the last name Slocum. In 1746, he married Ruth Moses, who was a member of the Wampanoag Nation from Cape Cod. Kofi worked for Holder Slocum, who owned a large farm and islands. Around 1750, Kofi moved his family to Cuttyhunk Island to care for sheep. Paul was born there, the seventh of ten children. In 1767, the family moved to a 116-acre farm in Dartmouth.

Paul's father died in 1772 when Paul was 13. Paul and his brother John took over running the farm and supported their mother and sisters. Around 1777-1778, Paul's brother John started using "Cuffe" as his last name. Paul later spelled his name "Cuffe" in his letters and other documents.

Becoming a Sailor

In 1773 and 1775, Paul Cuffe sailed on whaling ships, learning how to navigate. He called himself a mariner, which means a sailor. In 1776, during the American Revolutionary War, his whaling ship was captured by the British. Paul and his crew were held as prisoners in New York City for three months before being released.

Back home in Westport, Massachusetts, Paul continued to sail. In 1779, he used a small sailboat to deliver goods to Nantucket, even though pirates sometimes attacked his boat. He kept making these trips and eventually made a profit.

Fighting for Rights

In 1780, when Paul was 21, he and his brother John refused to pay taxes. They argued that free Black people in Massachusetts did not have the right to vote. They sent a petition to the government, saying it was wrong to tax them without letting them have a say. Their actions helped lead to a state law in 1783 that gave voting rights to all free male citizens in Massachusetts.

After the war, Cuffe started a shipping business with his brother-in-law, Michael Wainer. They built ships and sailed along the Atlantic Coast. Paul slowly earned more money and grew his fleet of ships. In 1789, they opened their own shipyard in Westport. He continued to build ships for the next 25 years. Many of Michael Wainer's sons became captains and crew members on their ships.

Marriage and Family Life

On February 25, 1783, Paul Cuffe married Alice Abel Pequit, a Wampanoag woman. They lived in Westport, Massachusetts, and had seven children: Naomi, Mary, Ruth, Alice, Paul Jr., Rhoda, and William.

Building a Shipping Empire

In 1787, Paul Cuffe and Michael Wainer built their first ship together, a 25-ton schooner called Sunfish. This was the start of a long partnership. Their next ship was the 40-ton schooner Mary, built in their own boatyard. They sold these ships to build a larger one, the 69-ton schooner Ranger, launched in 1796.

By 1800, Paul Cuffe had enough money to own half of the 162-ton barque Hero. At this time, he was one of the wealthiest African American or Native American people in the United States. His biggest ship, the 268-ton Alpha, was built in 1806. His favorite ship, the 109-ton brig Traveller, was built in 1807. In 1811, when Cuffe sailed the Traveller to Liverpool, a London newspaper reported that it was probably the first ship in Europe "entirely owned and navigated by Negroes."

Helping Sierra Leone

Paul Cuffe had been interested in the African colony of Sierra Leone for many years. He wanted to help the former slaves who had settled there. In 1810, he began his first trip to Sierra Leone.

Cuffe arrived in Freetown, Sierra Leone, on March 1, 1811. He explored the area and learned about the lives of the people. He met with Black business owners in the colony. Together, they wrote a request to the African Institution in London. They said the colony needed people to work in farming, trade, and whaling to grow. Cuffe and the Black business owners also started the Friendly Society of Sierra Leone. This group aimed to help free people in the colony become more successful.

Cuffe then sailed to Britain to get more help for the colony. He was welcomed by the leaders of the African Institution in London. They raised money for the Friendly Society. Cuffe was also given permission to continue his work in Sierra Leone. He returned to Sierra Leone, where he and the settlers made plans to build a grist mill, a saw mill, a rice factory, and a salt works.

Challenges and War

In late 1811, the U.S. government placed an embargo on British goods. This affected trade with Sierra Leone. In April 1812, when Cuffe's ship Traveller arrived in Newport, it was seized by U.S. officials. Cuffe went to Washington, D.C., to appeal. He met with President James Madison at the White House, possibly the first time an African American was a guest there. Madison ordered Cuffe's cargo returned, as he had not broken the law on purpose.

Madison also asked Cuffe about Sierra Leone, interested in the idea of sending free American Black people to Africa. Soon after, the War of 1812 began between the U.S. and Britain. As a Quaker, Cuffe was a pacifist and opposed the war. He was sad that the war stopped his efforts to help Sierra Leone. He tried to convince both countries to allow him to continue trading, but the U.S. Congress refused.

During the war, Cuffe visited Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. He spoke to groups of free Black people about the colony in Sierra Leone. He encouraged them to form Friendly Societies and communicate with each other. In 1813, Cuffe helped rebuild the Westport Friends Meeting House, paying about half the cost himself. The war caused Cuffe to lose ships and money.

After the War

The war ended in late 1814. After getting his finances in order, Cuffe prepared to return to Sierra Leone. On December 10, 1815, he sailed from Westport with 38 free Black colonists, including 18 adults and 20 children.

The trip cost Cuffe more than $4,000. The colonists arrived in Sierra Leone on February 3, 1816. The ship carried supplies like axes, hoes, a plow, and parts for a sawmill. However, Governor MacCarthy of Sierra Leone was not as welcoming this time. He was having trouble keeping order and was not eager for more immigrants. Also, Cuffe's cargo sold for less than it was worth. The new colonists were settled in Freetown. Cuffe believed that regular trade would help the society grow.

This expedition was very expensive for Cuffe. He had given each colonist a year's worth of supplies. The African Institution did not pay him back, and he lost over $8,000 due to high taxes. He knew he needed stronger financial support for future trips.

Later Life and Death

When he returned to New York in 1816, Cuffe showed proof that the colonists had settled well in Sierra Leone. During this time, many African Americans became interested in moving to Africa. The American Colonization Society (ACS) was formed for this purpose. Cuffe was asked for his advice by the ACS. However, he was worried by the clear racism shown by many ACS members, some of whom owned slaves. Some co-founders wanted to send freed Black people away to prevent them from causing trouble in slave societies.

In early 1817, Paul Cuffe's health got worse. He never returned to Africa. He died in Westport on September 7, 1817. His last words were, "Let me pass quietly away." Cuffe left behind a large estate worth almost $20,000. He left money and property to his wife, siblings, children, grandchildren, a poor widow, and the Friends Meeting House in Westport. He is buried in the graveyard behind the Westport Friends Meeting House. Many friends and family gathered for his funeral.

Paul Cuffe was a man of great hope and determination. He believed in doing what was right and worked hard to make things better for his race.

Honors and Legacy

- On January 16, 2009, Congressman Barney Frank spoke about Paul Cuffe as a "Voting Rights Pioneer" in the Congressional Record.

- On January 17, 2009, Governor Deval Patrick of Massachusetts declared Paul Cuffe Day to honor his 250th birthday.

- The Massachusetts State House and Senate also honored Paul Cuffe on January 17, 2009.

- On September 7, 2017, Governor Charlie Baker of Massachusetts declared Paul Cuffe Day to honor the 200th anniversary of his death.

- The Massachusetts House and Senate also honored Paul Cuffe on September 7, 2017.

- The New Bedford Whaling Museum opened the Captain Paul Cuffe Park in 2018.

- The Paul Cuffe Symposium Committee started the Paul Cuffe Heritage Trail in 2017. This trail celebrates Native American and African American history from New Bedford to Westport, honoring Cuffee Slocum, Paul Cuffe, and Michael Wainer.

- The Paul Cuffee Maritime Charter School was opened in 2001 in Providence, Rhode Island, for young people.

- The Paul Cuffe Math-Science Technology Academy ES was established in 2003 in Chicago, Illinois.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Paul Cuffe para niños

In Spanish: Paul Cuffe para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |