Opothleyahola facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

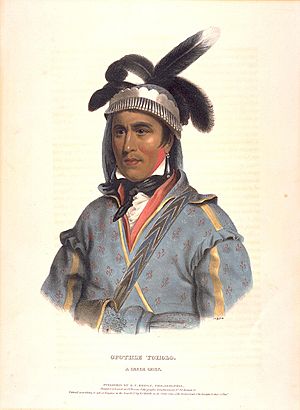

Opothle Yahola

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | c. 1778 Tuckabatchee town (Elmore County, Alabama)

|

| Died | March 22, 1863 (aged 85) Quenemo in Osage County, Kansas

|

| Resting place | near Fort Belmont in Woodson County, Kansas |

| Nationality | Muscogee |

| Other names | Laughing Fox |

| Occupation | Tribal chief |

Opothleyahola (around 1778 – March 22, 1863) was an important Muscogee Creek leader. He was known for being a great speaker. He served as a main speaker for the Upper Creek Council. He also worked hard to keep their traditional ways alive.

Even though he was a skilled diplomat, Opothleyahola led his people against the United States government. This happened during the Creek War. Later, he tried to stop the Treaty of Indian Springs (1825). But he was forced to sign a new treaty in 1832. He became a colonel and led his forces against other groups. These included the Lower Creek and the Seminole people.

Despite his efforts, Opothleyahola and his people were forced to move. They had to leave their homes in 1836. This move was part of the Indian removal to Indian Territory. They settled in an area called the Unassigned Lands.

During the American Civil War, Opothleyahola and many Creek people supported the Union. Because of fighting within the tribe, he led his followers to Kansas for safety. They fought three battles against their enemies along the way. Their journey became known as the Trail of Blood on Ice. This was because of the terrible conditions they faced. Many people suffered from a lack of supplies, sickness, and harsh winters. Opothleyahola died during the war in a refugee camp in Kansas.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Opothleyahola was born around 1778. His birthplace was Tuckabatchee, the main town of the Upper Creek. This area is now in Elmore County, Alabama. The Upper Creeks were the largest group in the nation. His name means "good speaker" or "good shouting child."

Historians believe his father was Davy Cornell, a mixed-blood Creek. His mother was a full-blood Creek, but her name is not known. Another historian, Angie Debo, thought his father might have been David Evans. He was a trader from Wales. He might have taught Opothleyahola English.

Opothleyahola had both European and Creek family. But he was born to a Creek mother. This meant he was considered part of her clan and tribe. He was raised as a Creek. The Creek people had a matrilineal system. This means that family lines and property came from the mother's side. The mother's family decided a child's status. Often, a boy's maternal uncles were very important in raising him. They would teach him men's roles and introduce him to tribal groups.

A Leader for His People

As more European Americans arrived, the Lower Creek leaders signed treaties. They gave up hunting lands in Georgia in 1790, 1802, and 1804. The Lower Creek had more contact with these newcomers. They had already lost land for hunting. So, they started farming more to survive.

Tensions grew between the Upper Creek and Lower Creek. This led to a civil war in 1812. The Red Sticks, from the Upper Creek, wanted to keep their old ways. They did not want to become like the European Americans. They also resisted giving up land. Opothleyahola is thought to have joined the British. This was against the U.S. forces in the War of 1812.

He was part of the Red Sticks in the Creek War of 1813–1814. This war ended when General Andrew Jackson defeated them. This happened at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. After this loss, Opothleyahola promised to be loyal to the U.S. government.

Standing Up for Land

Later, Opothleyahola became a very important and skilled speaker. He was chosen as the Speaker for the chiefs. This was a special role on the National Council. He later became known as a "diplomatic chief."

Opothleyahola also became a successful trader. He owned a large cotton plantation of 2,000 acres. This was near North Fork Town. Like other Creek and Five Civilized Tribes members, he had enslaved African Americans working on his plantation. He also adopted some European-American ways. He joined the Freemasons and became a Baptist.

Some Lower Creek chiefs signed the second Treaty of Indian Springs (1825). They did this without the agreement of the whole tribe. This treaty gave up most of the remaining Creek lands in Georgia. In return, they would get money and land west of the Mississippi River. The Creek National Council was worried. They made a law that said giving up land without tribal agreement was a serious crime.

The National Council, with Opothleyahola's support, sentenced William McIntosh to death. McIntosh and other chiefs had signed the 1825 Treaty. A chief named Menawa led 200 warriors. They attacked McIntosh's plantation. They killed him and another chief. They also burned McIntosh's house.

Fighting for Rights

The Creek elders knew they needed good negotiators. They needed to present their case to the U.S. government. Opothleyahola was a great speaker, but he did not speak English well. So, they asked the Cherokee for help. Major Ridge, a Cherokee leader, suggested his son, John Ridge, and David Vann. These young men were well-educated and spoke English fluently. They traveled with Opothleyahola to help him.

The Creek National Council, led by Opothleyahola, went to Washington, D.C. They protested the 1825 treaty. They said the chiefs who signed it did not have the council's approval. President John Quincy Adams agreed with them. The U.S. government and the chiefs made a new treaty. This was the Treaty of Washington (1826). It had better terms for the Creek.

But officials in Georgia started forcing Native Americans off the lands. They claimed these lands under the 1825 treaty. Georgia also ignored a U.S. Supreme Court ruling from 1832. This ruling said Georgia's laws about Native American lands were against the Constitution.

When Alabama also tried to take over Creek lands, Opothleyahola asked President Andrew Jackson for help. But Jackson had already signed the 1830 Indian Removal Act. He wanted the Creek and other tribes to move west. With no other choice, the Upper Creek signed the Treaty of Cusseta on March 24, 1832. This treaty divided Creek lands into individual plots. People could sell their plots and move to Indian Territory. Or they could stay in Alabama as citizens.

In 1834, Opothleyahola went to Nacogdoches, Texas. He tried to buy land there for his people to share. He paid $20,000 to landowners. But pressure from both the Mexican and American governments made him give up the idea.

Forced to Move West

In 1836, the U.S. government made Opothleyahola a colonel. He led 1,500 of his warriors against other Creek groups. These groups had joined the Seminole in Florida. They were fighting against European-American settlement. Soon after, the U.S. Army gathered the remaining Creek and other Native American groups. They forced them to move to Indian Territory. This difficult journey became known as the "Trail of Tears."

In 1837, Opothleyahola led 8,000 of his people. They moved from Alabama to lands north of the Canadian River. This was in the Unassigned Lands (now part of Oklahoma). Over time, they started raising animals and growing grains. The land and climate there were not good for their old farming methods.

The Civil War and a Difficult Journey

At the start of the American Civil War, Opothleyahola and many Creek people stayed loyal to the U.S. government. They felt the Southern states had forced them to move from their homes. The Lower Creek and some other tribes grew cotton. They owned many enslaved people. They also had more connections with white settlers. These groups supported the Confederacy. The Confederacy promised them an Indian-controlled state if they won. Tensions grew within the Creek Nation. The Confederacy tried to make tribes have stricter rules about enslaved people.

Creek people with African ancestors did not like these proposed rules. They felt more connected to the Union. Enslaved African Americans who had escaped, free people of color, Chickasaw, and Seminole people gathered at Opothleyahola's plantation. They hoped to stay neutral in the war.

Choosing a Side

On August 15, 1861, Opothleyahola and chief Micco Hutko contacted President Abraham Lincoln. They asked for help for the loyal Creek people. On September 10, they received a positive reply. The U.S. government promised to help them. The letter told Opothleyahola to move his people to Fort Row in Wilson County, Kansas. There, they would find safety and aid.

On November 15, Confederate Col. Douglas H. Cooper led 1,400 men north. These included pro-Confederate Native Americans. He wanted to convince Opothleyahola to join the Confederacy. If not, he planned to "drive him and his party from the country." Opothleyahola believed the U.S. promises. He led his group, including Seminole under Halleck Tustenuggee, toward Kansas.

The Trail of Blood on Ice

Along the way, Opothleyahola's people had to fight three battles. They had lost many of their belongings when they left quickly. At Round Mountain, Opothleyahola's forces pushed the Confederates back.

In December, the loyalists faced a loss at Battle of Chusto-Talasah. Then they suffered a big defeat at the Battle of Chustenahlah. Opothleyahola lost about 2,000 of his 9,000 followers. This was due to battles, sickness, and harsh winter storms. Fort Row could not get enough supplies. It also lacked medical help for the refugees. The Creek had to move to Fort Belmont. But conditions were still very bad. Most of the Creek only had the clothes they were wearing. They lacked proper shoes and shelter. Many Creek people died that winter, including Opothleyahola's daughter.

A Sad End

Life for the Creek in Kansas remained very hard. Opothleyahola died in the Creek refugee camp. This was near the Sac and Fox Agency at Quenemo in Osage County, Kansas. He passed away on March 22, 1863. He was buried next to his daughter near Fort Belmont in Woodson County, Kansas.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |