Atlantic Creole facts for kids

Atlantic Creoles were a unique group of people from the 16th and 17th centuries. They mostly came from parts of Africa like the Kongo and Angola. But they also had strong family or cultural connections to Europe.

Many Atlantic Creoles lived in busy trading cities along the coast of West Africa. These cities were melting pots of different cultures. Some of these people were taken from Africa as enslaved people during the Atlantic slave trade. Historians say that because they knew many cultures, they were very good at trading, talking, and understanding different languages. Many who arrived as enslaved people in new lands even managed to become free.

Famous Atlantic Creoles in early Colonial America included Anthony Johnson, John Punch, and Emanuel Driggus. Over time, the first Atlantic Creoles in Colonial America blended into different groups. These included Black, White, Native, and Creole communities in the United States. In places like Latin America and the Caribbean, they helped shape the many different cultures there.

Contents

History of Atlantic Creoles

What is an Atlantic Creole?

The historian Ira Berlin (1998) used the term "Atlantic Creoles" to describe a special group of people. They arrived in the Chesapeake Bay area of Colonial America in the 1600s. These were often Black enslaved people who had mixed European and West Central African backgrounds. They came from trading cities on the Atlantic Coast of West Africa. These cities already had strong Creole cultures.

Berlin didn't just mean "mixed race" when he used the term. He used it for people who, through their experiences or choices, became part of a new culture. This culture grew along the Atlantic coast in Africa, Europe, and the Americas starting in the 1500s. Being part of this Atlantic Creole culture was often more about choice and experience than about skin color or family background.

Atlantic Creoles in Africa and Beyond

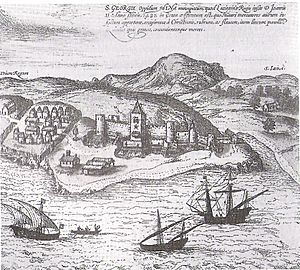

In the 1500s, European countries started to expand. This led to many different cultures mixing in West African trading ports. Atlantic Creoles often felt like outsiders in both African and European cultures. But people admired them for their skill in moving between these two worlds. They became known as expert traders and negotiators.

They also created a special Creole language. This language helped people who spoke different African languages talk to each other. Their ability to understand different cultures helped them succeed in the changing West African societies. However, they could also be enslaved if they lost favor with leaders, got into debt, or committed crimes. Then, they were sent to the Americas or Europe as part of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Some were also children of important African families sent to Europe to study.

As historian Jane Landers explains, Atlantic Creoles were "merchants, slave traders, linguists, sailors, artisans, musicians, and military figures." They interacted with many European and local groups. They helped create a new way of life across the Atlantic world.

Atlantic Creoles in Colonial America

Ira Berlin wrote that Atlantic Creoles were among the first enslaved people in the Chesapeake Colonies. He called them the "Charter Generation." This was up until the late 1600s. For the first 50 years of settlement, the differences between Black and White workers were not always clear. Often, both worked as indentured servants to pay for their travel. Enslaved people were not as separated as they would be later.

Working-class people lived together. Many White women and Black men formed relationships. Many of the new Creoles born in the colonies were children of European indentured servants and enslaved or bonded workers from West Africa. (Some Native Americans were also enslaved. Some enslaved Native Americans were brought to North America from the Caribbean and South America).

In 1662, a new law called partus sequitur ventrem was added to colonial law. This law said that children born in the colony would have the same status as their mother. So, if a mother was enslaved, her children were born into slavery. This was true even if their fathers were free or enslaved. This was different from traditional English law, which said children took the father's status.

Researchers like Paul Heinegg found that 80% of the free people of color in the Upper South during colonial times were born to White mothers. This meant they were born free. Their fathers were African or African-American. Some enslaved African men also gained freedom early on. But free mothers were the main reason most free families of color existed.

Berlin noted that most mixed-race "Atlantic Creoles" had Portuguese and Spanish fathers. This was mainly in the trading ports of West Africa. They often had surnames like Chavez, Rodriguez, and Francisco. In the Chesapeake Bay Colony, many Atlantic Creoles married their European neighbors. They adopted European surnames, became landowners and farmers, and even owned enslaved people themselves. These families became well-known. They had many free descendants by the time of the American Revolution.

In 2007, Linda Heywood and John Thornton studied new information about the slave trade. They found strong evidence for Berlin's idea. They showed that the first enslaved people, before 1660, mostly came from West Central Africa.

They also pointed out that in the Kingdom of Kongo (which is now northern Angola), leaders adopted Catholicism in the late 1400s. This was because of Portuguese influence. Many people in the kingdom then became Catholic. They created a special African-Catholic way of worship unique to their area. People often took Portuguese names when they were baptized. These kingdoms were Christian for almost 400 years. Many of their people were taken as enslaved people by the Portuguese.

Historians argue that many people from Kongo were brought to the North American colonies as enslaved people. This was especially true for South Carolina and Louisiana. Kongolese Catholics led the Stono Rebellion in 1739. Thornton and Heywood believe that about one out of every five African Americans today has ancestors from Kongo.

Historian Brunelle says that most early Atlantic Creoles with Iberian surnames in North America came from the Kongolese enslaved people. Not just from the small mixed-race groups around European trading posts. Many of these Kongolese were Christian, spoke several languages, and knew some European customs. The Dutch colonies in South America, the Caribbean, and New York also had many enslaved Atlantic Creoles from the Kingdom of Kongo.

Brunelle also suggests that European slave traders started bringing more enslaved Africans from outside the Atlantic Creole regions. This was to meet the growing need for workers by White colonists. The colonists found these non-Christian Africans to be very different culturally and ethnically. These differences, especially that the enslaved people were not Christian, made it easier for colonists to start seeing Africans as only enslaved property. This idea lasted through the 1700s and 1800s. The large number of these newer arrivals, who worked on the growing plantations, eventually formed much of African American culture. The influence of the Atlantic Creoles became less important over time.

Southern US Atlantic Creoles

Tidewater Creoles

The first Africans in Virginia came from parts of Angola that the Portuguese had settled since the late 1400s. Many of them spoke several languages and had been baptized. This mixing of cultures might be why some were able to gain freedom in colonial Virginia and Maryland.

Over time, slave laws became stricter. This caused the Tidewater Creoles to split up. Some were able to pass as White and join White communities. Others became Melungeon people. Some became free people of color, while the rest became part of the enslaved Black population.

Gullah Creoles

Historically, the Gullah region stretched from the coast of North Carolina down to Florida. The Gullah people and their language are also called Geechee. This name might come from the Ogeechee River in Georgia. Gullah was first used to describe the special English dialect spoken by these people. Now, it also refers to their unique language and ethnic identity. Georgia communities are called "Freshwater Geechee" or "Saltwater Geechee." This depends on whether they live on the mainland or the Sea Islands.

These Africans were enslaved from many different Central and West African groups. They worked on large plantations in rural areas. They were somewhat isolated from White people. Because of this, they developed a Creole culture that kept much of their African language and traditions. They also took in new influences from the region.

The Gullah people speak an English-based Creole language. It has many words from African languages. Its grammar and sentence structure are also influenced by African languages. Linguists sometimes call it "Sea Island Creole." It is similar to other Creole languages like Bahamian Creole, Turks and Caicos Creole, Barbadian Creole, Guyanese Creole, Belizean Creole, Jamaican Patois, and the Sierra Leonean Krio from West Africa. Gullah crafts, farming, fishing, folk beliefs, music, rice-based food, and storytelling all show strong influences from Central and West African cultures.

Louisiana Creoles

Louisiana Creoles are people whose families lived in colonial Louisiana. This was before it became part of the U.S., during the time when it was ruled by France and Spain. As an ethnic group, their ancestors are mainly African, French, Spanish, and Native American. German, Irish, and Italian immigrants also married into these groups. Louisiana Creoles share cultural ties. These include speaking French, Spanish, and Louisiana Creole languages. Most also practice Catholicism.

In the early 1800s, during the Haitian Revolution, thousands of refugees came to New Orleans. These included both Europeans and free Africans from Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). They often brought enslaved Africans with them. So many refugees arrived that the city's population doubled. As more refugees were allowed into Louisiana, Haitian people who had first gone to Cuba also arrived. These groups greatly influenced the city and its culture. Half of the White refugee population from Haiti settled in Louisiana, especially around New Orleans. Later immigrants in the 1800s, like Irish, Germans, and Italians, also married into Creole groups. Most of these new immigrants were also Catholic.

New Orleans also had a large historical population of Creoles of color. This group mostly included free people of mixed European, African, and Native American heritage. Most of these Creoles of Color later blended into Black culture. This was because of their shared history of slavery in the United States. Some chose to remain a separate but still part of the African American ethnic group. Many Creoles can also be found in the River Parishes: St. Charles, St. John, and St. James. However, most Creoles live in the greater New Orleans area or in Acadia.

Seminole Creoles

The Seminole Creoles are a group connected to the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly original Seminole people, Africans, Creoles, and escaped enslaved people (called maroons). These groups allied with Seminole groups in Spanish Florida. Many have Seminole family lines. But because of the stigma of having darker skin, they have often been called slaves or freedmen.

Historically, the Black Seminoles mostly lived in separate groups near the Native American Seminole. Some were held as enslaved people, especially by Seminole leaders. But the Black Seminoles had more freedom than enslaved people held by White people in the South or by other Native American tribes. This included the right to carry weapons.

Caribbean Atlantic Creoles

In many parts of the Southern Caribbean, the term Creole people means the mixed-race descendants of Europeans and Africans born on the islands. Over time, people from Asia also married into these groups. They eventually formed a common culture. This culture was based on their shared experience of living together in countries colonized by the French, Spanish, Dutch, and British.

A typical Creole person from the Caribbean has French, Spanish, Portuguese, British, and/or Dutch ancestors. These are mixed with sub-Saharan African ancestors. Sometimes, they also have Native Indigenous people of the Americas in their family tree. As workers from Asia came to the Caribbean, Creole people of color married people of Arab, Indian, Chinese, Javanese, Filipino, Korean, and Hmong backgrounds. These mixed families were especially common in Guadeloupe. The foods and cultures are a result of this mixing of influences.

"Kreyòl" or "Kweyol" or "Patois" also refers to the Creole languages in the Caribbean. These include Antillean French Creole, Bajan Creole, Bahamian Creole, Belizean Creole, Guyanese Creole, Haitian Creole, Jamaican Patois, Trinidadian Creole, Tobagonian Creole, and Sranan Tongo, among others.

See also

In Spanish: Criollo atlántico para niños

In Spanish: Criollo atlántico para niños