Melungeon facts for kids

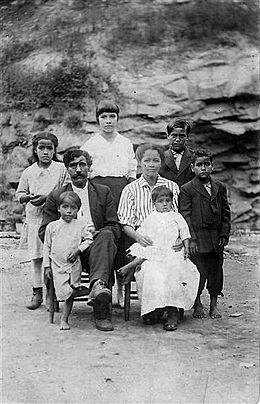

Arch Goins and family, Melungeons from Graysville, Tennessee, c. 1920s

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1950s estimate 200,000; currently unknown | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Originally in upper (East Tennessee, Southwest Virginia, and Eastern Kentucky; later migrations throughout the United States) | |

| Languages | |

| Appalachian English; other | |

| Religion | |

| Baptist; Pentecostal |

Melungeons (pronounced mə-LUN-jənz) are a group of people from the southeastern United States. Their ancestors were a mix of European and sub-Saharan African people. Many came to America as indentured servants in the mid-1600s, before slavery became common. This was an early example of different groups mixing together.

Historically, Melungeons lived in the Cumberland Gap area of the Appalachian Mountains. This region includes parts of East Tennessee, Southwest Virginia, and eastern Kentucky. The term "tri-racial" describes groups of people who have mixed European, African, and Native American backgrounds. There are many such groups, possibly as many as 200.

Contents

Who Are the Melungeons?

The history and identity of Melungeons have been much debated. Experts don't always agree on their exact origins, language, culture, or where they came from.

Melungeons can be seen as different families from various backgrounds who moved to frontier areas. They settled near each other and often married within their community. This happened mostly in Hancock and Hawkins counties in Tennessee, nearby parts of Kentucky, and in Lee County, Virginia. Their family lines can usually be traced back to colonial Virginia and the Carolinas. For a long time, until about 1900, they mostly married people from their own group.

Melungeons are known for having mixed ancestry. They don't look like they belong to just one race. Today, most descendants of families traditionally called Melungeon look like European Americans. They often have dark hair and eyes, and skin that is a bit darker or "olive." In the past, in the 1800s and early 1900s, Melungeons were sometimes called "Portuguese", "Native American", or "light-skinned African American". During the 1800s, free people of color sometimes said they were Portuguese or Native American to avoid being labeled as "black" in places where society was segregated.

Many Melungeon individuals and families are now seen as white, especially since the mid-1900s. They have tended to marry white people since before the 1900s.

Scholars don't all agree on which families are considered Melungeon. However, the English surname Gibson and the Irish surname Collins are often mentioned. Family history experts call them "core" surnames. Vardy Collins and Shep Gibson settled in Hancock County. Records like land deeds, slave sales, and marriage licenses show details about them and other Melungeons.

The original meaning of the word "Melungeon" is not clear. From the mid-1800s to the late 1900s, it mainly referred to the mixed-race descendants of the Collins, Gibson, and other related families in places like Newman's Ridge and Vardy Valley in Hancock and Hawkins counties, Tennessee.

Where Did They Come From?

In 1662, Virginia passed a law that said children born in the colonies would have the same social status as their mother. This meant that children of enslaved African women were born into slavery. But it also meant that children of free white or mixed-race women were born free, even if their father was an enslaved African man. The free descendants of these mixed families became most of the "free people of color" listed in the 1790 and 1810 US censuses. Early colonial Virginia was a "melting pot" of people. Before slavery became a strict racial system, white and black working-class people often lived and worked closely, forming relationships and marriages.

Some of these early mixed-race families were ancestors of the Melungeons. However, each family line needs to be traced separately. Over time, most people in the Melungeon group were of mixed European and African descent, sometimes also with Native American ancestry. Their ancestors had been free in colonial Virginia.

In 1950, Edward Price's study on mixed-blood groups said that children of European and free black parents also married people with Native American ancestry. In 1894, the U.S. Department of the Interior noted that Melungeons in Hawkins County "claim to be Cherokee of mixed blood." The term Melungeon has since sometimes been used for many different groups of mixed-race people.

In 1995, Paul Heinegg published a book showing that most free people of color in the 1790 and 1810 censuses had ancestors from colonial Virginia. These ancestors were children of white women and free, indentured, or enslaved African or African-American men.

In 2012, the family history expert Roberta Estes and other researchers from the Melungeon DNA Project found that Melungeon family lines likely started from mixed marriages between black and white indentured servants in Virginia in the mid-1600s. This was before slavery became widespread. They found that as laws against mixed-race marriages were put in place, these families married each other, forming a close-knit group. They moved together, sometimes with white neighbors, from western Virginia through the Piedmont frontier of North Carolina. They eventually settled mainly in the mountains of East Tennessee. The Melungeon DNA Project has confirmed that many people identified as Melungeon have mixed European and African ancestry.

Historical Records

Records show that free people of color moved with their European-American neighbors in the early 1700s to the frontiers of Virginia and North Carolina. There, they received land grants like their neighbors. For example, the Collins, Gibson, and Ridley (Riddle) families owned land next to each other in Orange County, North Carolina. In 1755, they were listed as "free Molatas" (mulattoes) and had to pay taxes. By settling in frontier areas, free people of color found better living conditions. They could escape some of the strict racial rules of Virginia and North Carolina's Tidewater areas.

Around 1767, some Melungeon ancestors reached the frontier New River area. They are listed on tax lists in Montgomery County, Virginia, in the 1780s. From there, they moved south into the Appalachian Range to Wilkes County, North Carolina. Some were listed as "white" on the 1790 census. They lived in a part that became Ashe County, where they were called "other free" in 1800.

The Collins and Gibson families were recorded in 1813 as members of the Stony Creek Primitive Baptist Church in Scott County, Virginia. They seemed to be treated as equals by the white members. The first known use of the term "Melungeon" is found in the records of this church.

From the Virginia and North Carolina frontiers, these families moved west into frontier Tennessee and Kentucky. The earliest known Melungeon in what is now northeast Tennessee was Millington Collins, who signed a deed in Hawkins County in 1802. However, there is some evidence that Vardy Collins and Shep Gibson had settled in Hawkins (now Hancock County) by 1790. Several Collins and Gibson households were listed in Floyd County, Kentucky in the 1820 census. They were classified as "free persons of color". On the 1830 censuses of Hawkins and nearby Grainger County, Tennessee, the Collins and Gibson families were listed as "free-colored". Melungeons lived in the part of Hawkins that became Hancock County in 1844.

By 1830, the Melungeon community in Hawkins County had 330 people in 55 families. In nearby Grainger County, there were 130 people in 24 families. According to Edward Price, Hawkins County had more free colored people in the 1830 census than any other county in Tennessee except Davidson (which includes Nashville). It also had more free colored families named Collins than any other county in the United States. Melungeon families have also been found in Ashe County in northwestern North Carolina.

Early records show that Melungeon ancestors were seen as mixed race. In the 1700s and early 1800s, census takers called them "mulatto", "other free", or "free persons of color". Sometimes they were listed as "white", sometimes as "black" or "negro", but almost never as "Indian". One family called "Indian" was the Ridley (Riddle) family, noted in a 1767 Pittsylvania County, Virginia, tax list. They had been called "mulattoes" in an earlier record from 1755. The Melungeon DNA Testing Program in 2012 stated that the Riddle family is the only Melungeon participant with historical records saying they had Native American origins, but their DNA is European. Among the participants, only the Sizemore family has documented Native American DNA.

A court case from 1858 in Johnson County, Tennessee, called Jacob Perkins vs. John White, helped define race at the time. In Virginia, if a free person was mostly white (one-eighth or less black), they were considered legally white and a citizen. The court said that if a person had no more than 1/8th "Negro or Indian blood," they were a citizen.

During the 1800s, because they married white spouses, families with Melungeon surnames were increasingly listed as white on census records. In 1935, a Nevada newspaper described Melungeons as "mulattoes" with "straight hair."

Becoming Part of Society

Historian Ariela Gross showed that how someone was seen, whether as "mulatto" or "white", often depended on their appearance and how the community saw them. It also depended on who they spent time with and if they acted like other citizens. Census takers were usually from the community, so they classified people based on how they were known locally. Racial categories were often unclear, especially for "mulatto" and "free person of color." In the early colonies and states, "mulatto" could mean a mix of African and European, African and Native American, European and Native American, or all three. These groups also married each other.

People were often identified by the company they kept and which ethnic culture they belonged to. There were differences between how people saw themselves and how others saw them. Because of slavery, laws often labeled mixed-race people with any African origin as African or "black." However, people of mixed African and Native American descent often identified and lived as Native Americans, especially if their mother was Native American. Many Native American tribes followed matrilineal systems, where children belonged to their mother's clan and got their social status from her people.

Because of the unclear terms and social attitudes towards mixed-race people, Native Americans who didn't live on reservations in the Upper South were often not recorded as "Indian." They were often reclassified as "mulatto" or "free people of color," especially as generations married neighbors of African descent. In the early 1900s, Virginia and some other states passed "one-drop rule" laws. These laws said that anyone with any known African ancestry had to be classified as black, no matter how they looked or identified.

After Virginia passed its Racial Integrity Act of 1924, officials even changed old birth and marriage records. They reclassified some mixed-race people or families who identified as "Indian" as "colored." These actions destroyed the official records of several Indian communities.

According to the Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, in his 1950 study, Edward Price suggested that Melungeons were families descended from free people of color (who had European and African ancestry) and mixed-race marriages between people of African ancestry and Native Americans in colonial Virginia. This territory included modern-day Kentucky and West Virginia.

Being Accepted

The families known as "Melungeons" in the 1800s were generally well-integrated into their communities. They might have still faced racism, but records show they usually had the same rights as whites. For example, they owned property, voted, and served in the Army. Some, like the Gibsons, even owned slaves as early as the 1700s.

Under Tennessee's first constitution in 1796, free men of color were allowed to vote. But after fears caused by the 1831 Nat Turner slave rebellion in Virginia, Tennessee and other southern states added new rules for free people of color. By its new constitution in 1834, Tennessee took away the voting rights of free people of color. This made them second-class citizens and kept them out of the political system.

During this time, several Melungeon men were tried in Hawkins County in 1846 for "illegal voting." They were suspected of being black or free men of color, which would make them unable to vote. They were found innocent. This likely happened because they showed the court they didn't have much black ancestry. The rules were not as strict then as the "one drop rule" laws of the 1900s. Often, a person's racial status was decided by how the community saw them. It also depended on whether they "acted white" by voting, serving in the militia, or doing other things white men did.

After the American Civil War and the Reconstruction Era, white southerners tried to regain political power and control over freedmen and free families like the Melungeons. White Democrat-controlled state governments passed Jim Crow laws. But arguments about money sometimes led to court cases about race.

For example, in 1872, a widowed woman's Melungeon ancestry was looked at in a trial in Hamilton County, Tennessee. Her late husband's relatives challenged her right to inherit money from him. They argued that a marriage between a white man and a woman known to be Melungeon was not legal because she had black ancestry. Based on what people in the community said, the court decided the woman did not have African ancestry, or not enough to matter.

During the time of segregation, a North Carolina law prevented "Portuguese" people (likely Melungeons, as North Carolina doesn't have many Portuguese Americans) from attending white-only schools. However, these "Portuguese" were not classified as Black, and they were not forced to attend Black schools.

Modern studies of Melungeon descendants in Appalachia show that they have become culturally very similar to their white neighbors. They share the Baptist religion and other community traits. As attitudes changed and people looked for more work, many descendants of early Melungeon families moved from Appalachia to other parts of the United States.

Old Stories and Myths

Even though Melungeons were culturally and linguistically similar to their European neighbors, their different physical appearance led to many stories about their identity. In the early 1800s, the negative term "Melungeon" began to be used by local white neighbors. Soon, local myths and stories started to appear about them. According to historian Pat Elder, the earliest myth was that they were "Indian" (specifically, "Cherokee"). Jack Goins, a Melungeon descendant and researcher, says that Melungeons claimed to be both Indian and Portuguese. An example was "Spanish Peggy" Gibson, wife of Vardy Collins.

A few ancestors might have been of mixed Iberian (Spanish and/or Portuguese) and African origin. Historian Ira Berlin noted that some early enslaved and free black people in the colonies were "Atlantic Creoles." These were mixed-race descendants of Iberian workers and African women from slave ports in Africa. Their male descendants grew up speaking two languages and traveled with Europeans as workers or slaves. Most of the early Melungeon ancestors, who moved from Virginia over time, were of northern European and African descent. Later generations in Tennessee married descendants of Scotch-Irish immigrants who arrived in the mid-to-late 1700s.

Based on historical evidence of Native American settlement, it's very unlikely that the original Melungeon families were descended from the Cherokee Nation. These families formed in the colonial era in the Virginia Tidewater areas, which were not Cherokee land. Some of their descendants might have later married isolated individuals of Cherokee or other Native American ancestry in East Tennessee. Melungeons in Graysville, Tennessee claimed Cherokee ancestors.

Anthropologist E. Raymond Evans wrote in 1979 that in Graysville, Melungeons strongly denied their Black heritage. They explained their physical differences by claiming to have Cherokee grandmothers. Many local white people also claimed Cherokee ancestry and seemed to accept the Melungeon claim.

In 1999, historian C. S. Everett thought that John Collins (recorded as a Sapony Indian expelled from Orange County, Virginia around 1743) might be the same as the Melungeon ancestor John Collins, who was called a "mulatto" in 1755 North Carolina records. But Everett later changed his mind after finding evidence that these were two different men. Only descendants of the second John Collins, identified as mulatto in the 1755 record, have a proven link to the Melungeon families of eastern Tennessee.

Other groups often suggested as Melungeon ancestors are the Black Dutch and the Powhatan Indian group. The Powhatan were an Algonquian-speaking tribe who lived in eastern Virginia when Europeans first arrived.

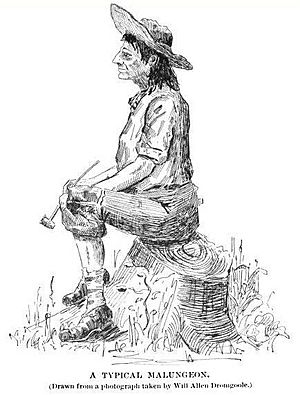

Stories about Melungeon origins continued in the 1800s and 1900s. Writers told folk tales of shipwrecked sailors, lost colonists, hidden silver, and ancient peoples like the Carthaginians or Phoenicians. Each writer added new parts to the myths, and more surnames were added to the list of possible Melungeon ancestors. Journalist Will Allen Dromgoole wrote several articles about the Melungeons in the 1890s.

In the late 1900s, some amateur researchers suggested that Melungeons might have ancestors who were Turks and Sephardi (Iberian) Jews. Writers David Beers Quinn and Ivor Noel Hume theorized that Melungeons came from Sephardi Jews who fled the Inquisition and sailed to North America. They also said that Francis Drake didn't send all the Turks he saved from the attack on Cartagena back home, but some came to the colonies. However, Janet Crain notes there are no written records to support this idea.

The paper on the Melungeon DNA Project, published by Paul Heinegg, Jack Goins, and Roberta Estes, shows that the ancestry of the people tested is mainly European and African. Only one person had Native American DNA from their father's side. There is no genetic evidence to support the Turkish or Jewish ancestry theories.

What Does the Name Mean?

There are many ideas about where the word Melungeon comes from. Linguists and many researchers believe it might come from the French word mélange, meaning "mixture." Or perhaps from [nous] mélangeons, meaning "[we] mix/mingle." This idea is also found in several dictionaries. Many French Huguenot immigrants came to Virginia from 1700, and their language could have contributed the term.

Joanne Pezzullo and Karlton Douglas think a more likely origin for Melungeon, given that English was the main language, might be from the old English word malengin (also spelled mal engin). This word meant "guile," "deceit," or "ill intent." It was used by Edmund Spenser in his poem, The Faerie Queene (1590–1596), which was popular in Elizabethan England. The phrase, "harbored them Melungins," would mean "harbored someone of ill will" or "harbored evil people," without referring to any specific ethnic group.

Another idea traces the word to malungu (or malungo), a Luso-African word from Angola. It means "shipmate" and comes from the Kimbundu word ma'luno, meaning "companion" or "friend." The word, spelled as Melungo and Mulungo, has been found in many Portuguese records. It is said to be a negative word that Africans used for people of Portuguese or other white ancestry. If so, the word likely came to America through people of African ancestry.

Kennedy (1994) suggests the word comes from the Turkish melun can (from Arabic mal`un jinn), which supposedly means "damned soul." He thinks that at the time, "condemned soul" was a term Turks used for Muslims captured and enslaved on Spanish galleons.

Some writers try to link the word Melungeon to an ethnic origin of the people it describes, but there's no proof for this. It seems the name was an exonym, meaning it was a name given to these mixed-race people by their neighbors, no matter their own origin.

In 1840, a newspaper in Jonesborough, Tennessee, called Brownlow's Whig, published an article titled "Negro Speaking!" The publisher called a rival politician an "impudent Malungeon from Washington City a scoundrel who is half Negro and half Indian," and then a "free negroe." He didn't name the politician.

Modern Identity

The term Melungeon was once considered an insult. It was a label for Appalachians who looked or were thought to be of mixed-race ancestry. In southwest Virginia, the term Ramp was used similarly for mixed-race people. This term is still seen as negative.

In 1943, Virginia's State Registrar of Vital Statistics, Walter Ashby Plecker, sent a letter to county officials. He warned against "colored" families trying to pass as "white" or "Indian," which was against the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. He listed specific surnames by county, including: "Lee, Smyth and Wise: Collins, Gibson, (Gipson), Moore, Goins, Ramsey, Delph, Bunch, Freeman, Mise, Barlow, Bolden (Bolin), Mullins, Hawkins (chiefly Tennessee Melungeons)". (Lee County, Virginia borders Hancock County, Tennessee.) He ordered offices to reclassify members of certain families as black. This caused many families to lose records that showed their continued identity as Native American.

Different researchers have made their own lists of core Melungeon family surnames. Usually, specific family lines need to be traced to confirm this identity. For example, DeMarce (1992) listed Hale as a Melungeon surname.

By the mid-to-late 1800s, the term Melungeon seemed to be used most often for the mixed-race families of Hancock County and nearby areas. Other uses of the term in print from the mid-1800s to early 1900s have been collected online. The spelling of the term varied a lot, which was common then. Eventually, "Melungeon" became the standard spelling.

Since the late 1960s, more and more people who identify with the group have started using the term "Melungeon." This change might be because of a popular outdoor play called Walk Toward the Sunset, which started in 1969 in Sneedville. The play showed Melungeons as native people of unclear race who were wrongly seen as black by white settlers. Since the play showed Melungeons in a positive way, many people began to identify themselves with the term for the first time. The play helped bring new interest to Melungeon history. The civil rights movement and social changes of the 1960s also helped people accept the group more widely. New facts about people identified as Melungeons have been found through historical and family research.

Since the mid-1990s, popular interest in Melungeons has grown a lot. Many descendants have moved away from the original areas. Writer Bill Bryson wrote about them in his book The Lost Continent (1989).

N. Brent Kennedy, who is not a specialist, wrote a book about his claimed Melungeon roots, The Melungeons: The Resurrection of a Proud People (1994). Kennedy's book was controversial. He suggested that Abraham Lincoln and Elvis Presley were Melungeons. He also believed there were pre-Columbian Welsh and Phoenicians/Carthaginians in North America. He dismissed them as related because he thought Melungeons don't look Welsh, and the time from any Phoenicians in North America to today (2500 years) would likely not allow their physical appearance to remain. With the internet, many people are researching family history, and the number of people identifying as having Melungeon ancestry has grown quickly. Some people started identifying as Melungeons after reading about the group online and finding their surname on a growing list of "Melungeon-associated" surnames. Others believe they have certain "characteristic" physical traits or health conditions, or assume that having mixed-race heritage means they are Melungeon.

For example, some Melungeons are said to have shovel-shaped incisors, a dental feature more common in Native Americans and Northeast Asians, but not only in them. After an unproven idea, made popular by N. Brent Kennedy, that Melungeons are of Turkish origin, some people have identified as having an enlarged external occipital protuberance, called an "Anatolian bump."

Academic historians have not found any proof for these ideas. The results from the Melungeon DNA Project also do not support them. As mentioned before, this analysis shows that Melungeon descendants mostly have northern European and African DNA ancestry.

Internet sites promote the idea that Melungeons are more likely to get certain diseases, like sarcoidosis or familial Mediterranean fever. Medical centers have noted that neither of these diseases is limited to one group of people.

Kennedy's claims about his family connections to this group have been strongly questioned. The professional family history expert and historian, Virginia E. DeMarce, reviewed his 1994 book. She found that Kennedy's proof of his Melungeon ancestry was seriously flawed. He had a very unclear definition of Melungeons, even though the group had already been studied and documented by other researchers. She criticized Kennedy for trying to include people who might have had non-northern European ancestry. She said he didn't properly consider existing historical records or accepted family history practices in his research. He claimed his ancestors were persecuted for racial reasons. However, she found that his named ancestors were all classified as white in records, held various political jobs (showing they could vote and were supported by their community), and owned land. Kennedy responded to her criticism in his own article.

The Ridgetop Shawnee Tribe of Indians in Kentucky, which is not recognized by the federal or state government as an Indian tribe, claims that most families in its area commonly identified as Melungeon are partly Native American. The organization says their ancestors moved to the region in the late 1700s and early to mid-1800s. Most of these families claimed Ridgetop Shawnee heritage to explain their dark skin and Indian features and to avoid racial unfairness. In 2010, the Kentucky General Assembly passed resolutions that recognized the contributions of the Ridgetop Shawnee Tribe of Indians to the state.

Similar Groups

Here are other multi-racial groups that were once called "tri-racial isolates." Some identify as Native American and have received state recognition, like six tribes in Virginia.

- Delaware

- Nanticoke-Moors (and in Maryland) Nanticoke groups in Delaware and New Jersey (where they are mixed with Lenape) have received state recognition. Most had left the area in the late 1700s and 1800s.

- Florida

- Dominickers of Holmes County in the Florida Panhandle

- Indiana

- Ben-Ishmael Tribe, sometimes called "Grasshopper Gypsies"

- Louisiana

- Redbones (and in Texas)

- Maryland

- Piscataway Indian Nation, formerly also known as We-Sorts, one of three Piscataway-related groups recognized as Native American tribes by the state

- New Jersey and New York

- Ramapough Mountain Indians (also known as "Jackson Whites") of the Ramapo Mountains, recognized by both New Jersey and New York as Native Americans

- North Carolina

- Coree or "Faircloth" Indians of Carteret County

- Haliwa-Saponi, recognized by the state as Native American

- Lumbee, recognized by the state as Native American

- Person County Indians, also known as "Cubans and Portuguese"

- Ohio

- Carmel Indians of Highland County

- South Carolina

- Red Bones (Note: different from the Gulf States Redbones)

- Turks

- Brass Ankles

- Virginia

- Monacan Indians (also known as "Issues") of Amherst and Rockbridge counties, recognized by the state of Virginia and the federal government (2018) as a Native American tribe, along with five other Virginia tribes

- West Virginia

- Chestnut Ridge people of Barbour County (also known as Mayles or, negatively, "Guineas")

Each of these groups of mixed-race people has its own history. There is evidence that some of them are connected, going back to common ancestors in colonial Virginia. For example, the Goins surname group in eastern Tennessee has long been identified as Melungeon. The surname Goins is also found among the Lumbee of southern North Carolina, a mixed-race group recognized by the state as a Native American tribe. In most cases, the mixed-race families need to be traced through specific branches, as not all descendants were considered to be Melungeon or part of other groups.

Images for kids

-

Arch Goins and family, Melungeons from Graysville, Tennessee, c. 1920s

See also

In Spanish: Melungeon para niños

In Spanish: Melungeon para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |