Wilma Mankiller facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Wilma Mankiller

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation | |

| In office December 14, 1985 – August 14, 1995 |

|

| Preceded by | Ross Swimmer |

| Succeeded by | Joe Byrd |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Wilma Pearl Mankiller

November 18, 1945 Tahlequah, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Died | April 6, 2010 (aged 64) near Tahlequah, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses |

Hugo Olaya

(m. 1963; div. 1974)Charlie Soap

(m. 1986) |

| Children | 2 |

| Education | Skyline College San Francisco State University (BA) University of Arkansas |

Wilma Pearl Mankiller (Cherokee: ᎠᏥᎳᏍᎩ ᎠᏍᎦᏯᏗᎯ, romanized: Atsilasgi Asgayadihi; November 18, 1945 – April 6, 2010) was an important Native American leader. She was the first woman ever elected to be the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Wilma was born in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

When she was 11, her family moved to San Francisco as part of a government program. This program encouraged Native Americans to move to cities. After high school, she got married and had two daughters. Inspired by the social changes of the 1960s, Wilma became involved in Native American rights. She helped with the Occupation of Alcatraz and worked with the Pit River Tribe on land issues. For five years, she worked as a social worker, helping children.

In 1976, Wilma returned to Oklahoma. The Cherokee Nation hired her to help with economic projects. She was very good at writing grant applications to get money for projects. By the early 1980s, she led the new Community Development Department for the Cherokee Nation. She created new projects that helped people in rural areas solve their own problems. For example, her project in Bell, Oklahoma, helped people get clean water. This project was even shown in a movie called The Cherokee Word for Water.

Wilma's leadership skills impressed the Principal Chief, Ross Swimmer. He asked her to run as his deputy in the 1983 tribal elections. When they won, she became the first elected woman to be Deputy Chief of the Cherokee Nation. In 1985, when Chief Swimmer left for a job in the federal government, Wilma became the Principal Chief. She served until 1995. During her time as Chief, the Cherokee government built new health clinics and started education programs. She also helped the tribe earn money through businesses and manage its own funds.

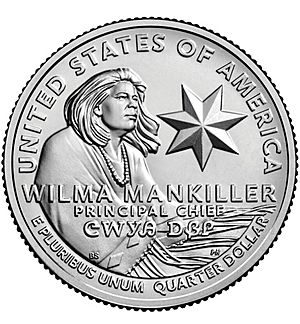

After leaving politics, Wilma continued to be an activist. She wrote books, including her best-selling autobiography, Mankiller: A Chief and Her People. She also gave many talks about health, tribal rights, women's rights, and cancer awareness. Wilma faced many serious health problems throughout her life. She received many awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which is the highest award for a civilian in the U.S. In 2021, it was announced that her image would appear on a U.S. quarter coin.

Contents

Wilma's Early Life (1945–1955)

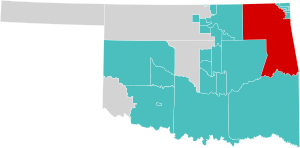

Wilma Pearl Mankiller was born on November 18, 1945. She was born at the Hastings Indian Hospital in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Her father, Charley Mankiller, was a full-blooded Cherokee. His family had been forced to move from Tennessee to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears in the 1830s. Her mother, Clara Irene, had European ancestors.

The name "Mankiller" (Asgaya-dihi in Cherokee) was a traditional Cherokee military rank. It was like being a captain or major. Wilma's Cherokee name, A-ji-luhsgi, means flower. Her parents lived on her grandfather's land, called "Mankiller Flats." This land was near Rocky Mountain, Oklahoma in Adair County, Oklahoma.

Wilma was one of eleven children. In 1948, her father, uncle, and brother built a house for the family. It was a small house with no electricity or running water. The family lived in "extreme poverty." They hunted, fished, and grew vegetables to eat. They also grew peanuts and strawberries to sell. Wilma went to a three-room schoolhouse in Rocky Mountain. Her family spoke both English and Cherokee at home. Her mother taught the children about their Cherokee heritage.

Moving to San Francisco (1956–1976)

In 1955, a bad drought made it hard for the family to find food. The Indian Relocation Act of 1956 was a government program. It helped Native families move to cities. Government agents promised better jobs and living conditions. In 1956, when Wilma was 11, her father decided to move the family to California. They chose California because her mother's mother lived there.

The family took a train from Stilwell, Oklahoma, to San Francisco. They were promised an apartment, but there wasn't one when they arrived. They stayed in a poor hotel for weeks. Even after moving to Potrero Hill, the family struggled financially. They felt alone because they had few Native American neighbors.

Wilma and her siblings went to school, but it was hard. Other students made fun of her last name and her clothes. Wilma felt sad and shy. She ran away to her grandmother's farm for a year. When she returned, her family had moved to Bayview–Hunters Point, San Francisco. This neighborhood had a lot of crime. Wilma still felt alone but started going to the San Francisco Indian Center. She graduated from high school in 1963.

After school, Wilma got a job and moved in with her sister. She met Hector Hugo Olaya de Bardi, an Ecuadorian college student. They married in 1963. They had two daughters, Felicia and Gina. While her husband went to school and worked, Wilma raised their children. But Wilma wanted more. She went back to school at Skyline Junior College. For the first time, she really enjoyed learning.

Becoming an Activist

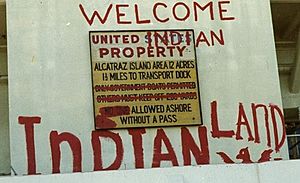

In the late 1960s, students began protesting the Vietnam War and fighting for civil rights. The American Indian Movement (AIM) was one of these groups. In 1969, the San Francisco Indian Center burned down. This led to the Occupation of Alcatraz Island by Native American activists.

The Alcatraz occupation inspired Wilma to become an activist. She had not been involved before. She started meeting with other Native Americans who supported the occupation. She helped by raising money and gathering supplies like blankets and food. During this time, Wilma learned how to organize and do legal research. She also learned that she had the same kidney disease as her father.

Working as a Social Worker

After her father died in 1971, Wilma returned to Oklahoma for his burial. When she came back to California, she studied social welfare at San Francisco State University. She started to become more independent. She took her daughters to Native American events. On her travels, she met members of the Pit River Tribe. She joined their fight to get money for lands taken from them. For five years, she helped them with legal documents and fundraising.

Wilma also started the Native American Youth Center in East Oakland. She found a building and asked for volunteers to help. The community gave a lot of support. In 1974, Wilma and her husband divorced. She moved to Oakland with her daughters. She worked as a social worker at the Urban Indian Resource Center. She researched child abuse and worked to keep Native children with Native families. This work helped create the Indian Child Welfare Act. This law made it illegal to place Native children with non-Native families.

Returning to Oklahoma

Community Development Work (1976–1983)

In 1976, Wilma's mother moved back to Oklahoma. Wilma and her daughters soon followed. She built a small house near her mother's home. In 1977, the Cherokee Nation hired her to work on a program for young Cherokees. She also took more classes and earned her college degree. She then studied community development at the University of Arkansas. She continued to work for the tribe, helping with health care, language services, and youth programs.

In 1979, Wilma was in a serious car accident. Her friend, Sherry Morris, died. Doctors thought Wilma might not walk again. After many surgeries, she could walk with crutches. While recovering, she was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, a muscle disease. She had more surgeries and chemotherapy. She returned to work in December 1980.

Wilma's first community project was in Bell, Oklahoma. She got a grant for a water system. She asked community members to help lay 16 miles of pipe. This project showed how people could work together to improve their own lives. Wilma worked with Charlie Soap on this project. Its success became a model for other tribes. In 1981, Chief Ross Swimmer made her the first director of the new Community Development Department. Wilma raised millions of dollars for similar programs. She believed in "self-help," where people found their own solutions. Chief Swimmer was so impressed that he asked her to run for Deputy Chief with him.

Entering Politics (1983–1995)

Deputy Chief (1983–1985)

In 1983, Wilma ran as Deputy Chief with Ross Swimmer. Swimmer was a Republican, and Wilma was a Democrat. They both wanted the tribe to be more independent. Swimmer focused on tribal businesses, while Wilma wanted to improve housing and health care in rural areas.

Wilma faced sexism because she was a woman. In traditional Cherokee society, women had a lot of influence, but not titled government positions. She received threats, and her car tires were cut. But Swimmer supported her. They won the election, and Wilma became the first woman elected Deputy Chief of the Cherokee Nation. Some people tried to challenge the election results, but courts ruled in their favor.

As Deputy Chief, Wilma led the Tribal Council. Some council members were not supportive because she was a woman. She focused on areas not controlled by the council. She worked to bring together Cherokees with different backgrounds. She expanded the Cherokee Heritage Center and literacy programs. She also changed how council members were elected. This change meant that smaller communities had more say.

Principal Chief (1985–1995)

In 1985, Chief Swimmer resigned. Wilma became the first female Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. She was sworn in on December 5, 1985. Wilma became famous around the world. She helped improve how Native Americans were seen. She showed that Cherokee traditions of cooperation and respect for nature were good examples for everyone. She also talked about how Cherokee women were valued before outside influences changed things.

Wilma used her public attention to tell Cherokee voters about her goals. She wanted to improve housing and health services. Within five months, she was named American Indian Woman of the Year. She also received honorary degrees from universities.

In 1986, Wilma and Charlie Soap got married. This caused some talk, and Charlie resigned from his job. Wilma decided to run for re-election. She convinced voters that the tribe could work with state and federal governments. Charlie, who was a full-blood Cherokee, helped her talk to people. He spoke in Cherokee about the traditional role of women. Wilma focused on how government budget cuts affected the tribe. She believed that business growth needed to be balanced with solving social problems.

Before the election, Wilma was in the hospital for her kidney disease. Her opponents said she was too sick to lead. But Wilma won the election. She used her fame to fight negative ideas about Native people. She highlighted their culture and strengths. She was named Ms. magazine's Woman of the Year in 1987.

One of Wilma's first goals was to keep the Talking Leaves Job Corps Center open. She found a new location for it. In 1987, her Kenwood Project won a national award for community development. She also pushed the Cherokee Heritage Center to earn its own money. When a law about tribal gambling passed, Wilma was careful. She did not want gambling to bring crime. Later, bingo parlors did become a big source of income for the tribe. She also refused requests for the tribe to store nuclear waste.

Wilma started the Private Industry Council. This group brought government and businesses together to create jobs. She helped tribal members start their own businesses. She also supported a tribal electronics company and a hydroelectric plant. Her government also sued the U.S. government for money. They wanted payment for resources taken from the Arkansas River. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Cherokee and other tribes owned the riverbanks.

In 1988, Wilma won a national award for her leadership. She met with President Reagan to discuss Native issues. She was disappointed that he did not listen. But the meeting helped her public image. She also made an agreement with Oklahoma about taxes. This allowed the tribe to collect state taxes and keep some of the money.

In 1990, Wilma's kidney failed. Her brother Don donated a kidney, and she had a transplant. She returned to work quickly. She signed an agreement for the Cherokee Nation to manage federal funds itself. This was part of a new policy called "self-governance." It allowed tribes to decide how to use money for their own needs. During her first full term, her government built new health clinics and started education programs. She received honorary degrees from Yale University and Dartmouth College.

Wilma also worked to solve problems with the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians. Her administration created a tribal court. They also made agreements with law enforcement agencies. This helped deal with legal issues on tribal lands.

In 1991, Wilma ran for re-election and won with 83% of the vote. She met with President George H. W. Bush, who was more open to tribal leaders. She hoped for a new era of "government-to-government relationships." She opposed centralizing Indian education. She also fought against a law that would tax cigarettes sold at tribal shops. She spent a lot of time trying to get money for the tribe's mineral rights in the Arkansas River.

Wilma's government reopened Sequoyah High School. She started a program to connect Cherokee mentors with girls at the school. She also focused on Cherokee identity. She helped document groups claiming Cherokee heritage. She worked to make sure only real Native artists could sell their work as "Indian Art."

Wilma did not want to make it easier for groups to claim tribal recognition. She believed it could allow people to falsely claim Native heritage. During her time as chief, the Cherokee tribal council passed laws. These laws required people to prove their Cherokee ancestry to enroll in the tribe.

In 1992, Wilma supported Bill Clinton for president. She became a very important Native American leader. Her autobiography, Mankiller: A Chief and Her People, became a best-seller in 1993. She received many awards, including being inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame. In 1994, she was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame. She also helped organize a summit for leaders of all federally recognized tribes. This meeting helped tribal leaders and government officials solve problems.

In 1995, Wilma was diagnosed with lymphoma. She decided not to run for chief again because of her health. Joe Byrd became the next Principal Chief. Wilma did not attend his inauguration. She was worried that Byrd would fire her staff. She authorized payments for workers leaving office. A lawsuit was filed against her, but it was later dropped. Wilma said, "We've had daunting problems... but I believe in the old Cherokee injunction to 'be of a good mind'."

When Wilma left office, the Cherokee Nation had grown from 68,000 to 170,000 citizens. The tribe was earning about $25 million each year from businesses. She had also secured $125 million each year in federal aid for education, health, and housing. She had helped the tribe gain more control over its own funds.

Returning to Activism (1996–2010)

After her time as chief, Wilma became a visiting professor at Dartmouth College in 1996. She taught in the Native American Studies program. She also started a national lecture tour. She spoke about health care, tribal rights, women's rights, and cancer awareness. She spoke to many groups, including universities and women's organizations.

In 1998, President Clinton gave Wilma the Presidential Medal of Freedom. This is the highest award for a civilian in the United States. Soon after, she had another kidney failure. Her niece donated a kidney for her second transplant. Wilma quickly returned to her lecture tours and worked on four books. In 1999, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She had surgery and radiation treatment. That same year, a book she helped edit, The Reader's Companion to U.S. Women's History, was published.

Wilma continued to write and speak. In 2004, she co-authored Every Day Is a Good Day: Reflections by Contemporary Indigenous Women. She also worked to raise awareness about breast cancer. In 2006, she sent a simple pair of walking shoes to a museum exhibit. She chose them because she had worn them all over the world. They showed her normal life and her strong determination. In 2007, she gave a special lecture for Oklahoma's 100th anniversary. She continued her work until her death.

Wilma's Death and Lasting Impact

In March 2010, Wilma's husband announced she was very sick with pancreatic cancer. Wilma died on April 6, 2010, at her home in Oklahoma. About 1,200 people attended her memorial service. Many important people were there, including the Cherokee Chief, Oklahoma Governor, and Gloria Steinem. Statements from Bill and Hillary Clinton and President Barack Obama were read. Wilma was buried in her family cemetery. She was also honored by the U.S. House of Representatives.

Wilma Mankiller's important papers are kept at the University of Oklahoma. She received 14 honorary doctorates. She made a lasting impact on her state and the nation. She helped build communities and guided her tribe. During her time as Principal Chief, she made the Cherokee Nation stronger. She helped improve how the tribe worked with the U.S. federal government. She was an inspiration to Native and non-Native Americans, and a role model for women and girls. Wilma once said, "Prior to my election, young Cherokee girls would never have thought that they might grow up and become chief." A scholarship was named in her honor to help Indigenous women attend leadership conferences.

A 2013 movie, The Cherokee Word for Water, tells the story of the Bell waterline project. This project helped start Wilma's political career. It also began her friendship with her future husband, Charlie Soap. The film was important to Wilma because it showed the strength of Native people. The Mankiller Foundation, named after her, helps with education and community projects. In 2015, the Wilma P. Mankiller Health Center in Stilwell was expanded. It is one of the busiest hospitals in the Cherokee Nation. In 2017, a documentary film called Mankiller was released. It tells her life story. In 2018, Wilma was honored in the National Native American Hall of Fame.

In 2021, it was announced that Wilma Mankiller's image would appear on a quarter-dollar coin. This is part of the United States Mint's "American Women Quarters" Program.

|

See also

In Spanish: Wilma Mankiller para niños

In Spanish: Wilma Mankiller para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |