Chief Vann House Historic Site facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Chief Vann House

|

|

Chief Vann House

|

|

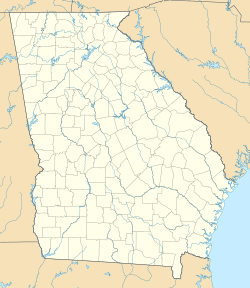

| Location | 82 Highway 225 N, Chatsworth, Georgia |

|---|---|

| Built | 1804 |

| Architect | Henry Chandlee Forman |

| Architectural style | Federal |

| NRHP reference No. | 69000044 |

| Added to NRHP | October 28, 1969 |

The Chief Vann House was the very first brick home built in the Cherokee Nation. People often called it the "Showplace of the Cherokee Nation" because it was so grand. This historic house belonged to a powerful Cherokee leader named James Vann. Today, it is a Georgia Historic Site and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It's one of the oldest buildings still standing in northern Georgia. You can find it in Murray County, near Chatsworth. From the house, you can see the beautiful Cohutta Mountains about 10 miles (16 km) away.

Contents

Building the Vann House

As James Vann became a very successful businessman and an important chief, he decided to build a large brick house. He wanted it to show his high status. He hired professional architects to help design it. The Moravian people, who also helped educate local Cherokees, assisted with the building work.

In July 1803, construction began with a man named Vogt and Dr. Henry Chandlee Forman. The house was finished in early 1804. Both the outside walls, which are about eighteen inches thick, and the inside walls, about eight inches thick, are made of solid brick. These bricks were made from red clay found right on the Spring Place Plantation where the house stands. Even the nails and hinges were handmade in Vann's own blacksmith shop. Only the walls on the third floor were made of plaster over wood.

The main bricklayer for the house was Robert Henry Howell. He was born in Virginia and passed away in 1834. He is buried in the Moravian cemetery nearby.

The Vann House combines two styles: late Federal-style architecture and early Georgian style. It has two full floors and a third half-story. The first and second floors have tall twelve-foot ceilings. The third floor's roof is only six feet high.

The first and second floors each have three main rooms. On both levels, there's a room on the east, a room on the west, and a hallway in between. On the first floor, the dining room is on the east, and the drawing-room (or living room) is on the west. Upstairs, the east room was the master bedroom, and the west room was for guests. The third floor was different. It was used for storage when James lived there and later as children's rooms when his son Joseph owned it.

On the third floor, there are two rooms. One, thought to be for boys, is two-thirds the width of the house and has two closets. The other room, for girls, is one-third the width of the house. This room could be closed off from the boys' room for more privacy.

The Vann House also has a basement with two separate rooms. One was used as a wine cellar. The other might have been used for storage or other purposes.

The inside of the house is beautifully decorated with colors like red, blue, green, and yellow. White was used as a background color. There are two ideas about why these colors were chosen. One idea is that they represent nature: red for Georgia's red clay, blue for the sky, green for trees and grass, and yellow for wheat and corn. The second idea is that these colors were popular in the Federal-style of that time.

These colors were common in homes from the late 1700s and early 1800s. However, the Vann House used colors differently. Most homes would have one color per room, like a "red room" or a "blue room." But in the Vann House, colors were mixed in almost every room, creating a multi-color look. You can still see this color scheme on the mantels, doorframes, and wainscoting, which are all original to the house.

The house's doors are special, too, and are called Christian doors. They have designs that look like a cross and an open Bible.

Besides the house, the 800-acre (3.2 km2) property had many other buildings. These included a blacksmith shop, six barns, five smokehouses, and a trading post. There were also over 1,000 peach trees and 147 apple trees.

James Vann lived in his grand house for five years. After his passing in 1809, his son, Rich Joe Vann, inherited the home.

Rich Joe's Vann House

After his father passed away, Rich Joe made his own improvements to the house. He hired a father and son team, John and James McCartney, to decorate the home between 1809 and 1818.

The McCartneys added all the beautiful woodwork you see today, including fancy ionic columns. They also built a very unusual feature: a "floating staircase" on the third floor. It looks like it's floating because the second landing of the stairs has no visible supports underneath it. It seems to hang in the air!

The Vann staircase is one of the oldest examples of cantilevered construction in Georgia. This means it's built so that one side is firmly supported, balancing the weight of the other side. Part of the staircase is built into a very thick brick wall, which acts like a counterweight. This design makes sure the stairs are always stable.

In 1819, President James Monroe was traveling from Augusta to Nashville. He had planned to stay at a simple Moravian mission. Instead, he visited the nearby Vann House and found it much more comfortable. He asked Rich Joe, who was only 20 years old, if he could spend the night there, and Rich Joe agreed.

Losing the Vann House

After the Georgia Gold Rush, new laws made things difficult for the Cherokee people. Rich Joe Vann hired a white man, Mr. Howel, to help manage the Vann House. However, a new Georgia law said white people could not work for Cherokees without a special permit. Rich Joe didn't know he was breaking this new law.

During this time, leading up to the Trail of Tears, two different people tried to claim the Vann House. Colonel William Bishop and the Georgia Guard tried to take the house because Rich Joe had hired a white man without a permit. At the same time, Spencer Riley claimed he had won the house in the Land Lottery of 1832. Colonel Bishop then forced Rich Joe out of his home.

Colonel Bishop used the house as his local office and let his brother, Absalom Bishop, live there. But Spencer Riley then moved into the house, claiming it was his. To get Riley to leave, Colonel Bishop placed a smoldering log on the cantilevered steps. This caused some damage to the house but made Riley leave, and Bishop's brother moved back in.

Even though Rich Joe and his family lost their home, he later sued the government. He was given $19,605 as payment, which was almost double what the house was worth back then.

In November of that year, a famous composer named John Howard Payne was held at the house for 13 days. Payne, who wrote the song "Home, Sweet Home," was accused of supporting the Cherokee people against the state of Georgia.

Bringing the Vann House Back to Life

Rich Joe and his family were finally forced to leave their home in March 1835. They moved to Webbers Falls, Oklahoma, as part of the Trail of Tears. They never returned to Georgia or their house.

Over many years, the Vann House had seventeen different owners. In 1952, a doctor named J. E. Bradford, who had bought the house in 1920, sold it to the Georgia Historical Commission and the State of Georgia. The house was in very bad shape; the roof had fallen off, and the weather was causing a lot of damage.

One of the past owners had added a room after Rich Joe left. A big project to restore the house began in 1958, led by Dicksie Bradley Bandy. It took six years to finish. They removed the extra room that wasn't part of the original house and repainted the home using its classic color scheme. Today, the house is managed by the Parks, Recreation, and Historic Sites division of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

Robert E. Chambers Interpretive Center

In 1999, the State of Georgia, the Cherokee people, the State of Oklahoma, and other supporters helped build a new museum. It's called the "Robert E. Chambers Interpretive Center" and is located next to the Vann House. It opened on July 27, 2002. This center honors the Cherokee people and their history. It also tells the stories of Chiefs James and Joseph Vann and shares the history of the Cherokee Nation over the last 200 years, including the sad story of the Trail of Tears. Robert E. Chambers was a local businessman from Chatsworth who supported the Cherokee people, and the center is named after him.

See also

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |