Mary Dyer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mary Dyer |

|

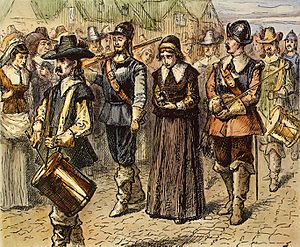

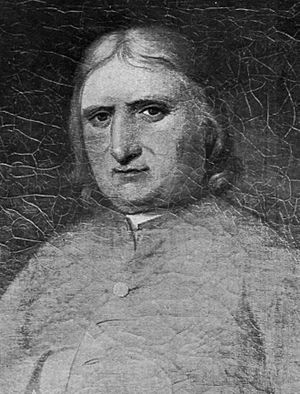

Dyer being led to the gallows in Boston in 1660, painted c. 1905 by Howard Pyle |

|

| Born | c. 1611 in England |

|---|---|

| Died | 1 June 1660 (aged 48–49) in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony |

| Nationality | English |

| Spouse | William Dyer (Dier, Dyre) |

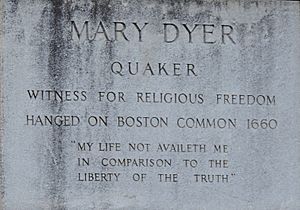

Mary Dyer (born Marie Barrett; around 1611 – June 1, 1660) was an English woman who moved to America. She was first a Puritan but later became a Quaker. She was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, because she kept breaking a Puritan law. This law banned Quakers from the colony. She is one of four Quakers who were executed, known as the Boston martyrs.

Mary and her husband, William Dyer, were Puritans. They wanted to change the Anglican Church from the inside. When King Charles I put more pressure on Puritans, many left England. Mary and William arrived in Boston by 1635.

They soon got involved in a big religious debate called the Antinomian Controversy. Mary and William strongly supported Anne Hutchinson. Because of this, William lost his right to vote and own weapons. They then left Massachusetts with many others. They started a new colony on Aquidneck Island (later Rhode Island).

In 1651, Mary Dyer went to England for over five years. During this time, she became a Quaker. The Puritans thought Quakers were very dangerous. Massachusetts made several laws against them. When Mary returned to Boston, she was put in jail and then sent away. She kept coming back, even when told she would be killed. She was almost executed once but was saved at the last moment. She returned to Boston one more time and was then hanged. She was the third of four Quaker martyrs.

Contents

Mary Dyer's Early Life

We don't know much about Mary Dyer's early life in England. Her marriage record shows her name as Marie Barret. She married William Dyer in London in 1633. He was a fish seller and a hat maker.

Mary was well-educated, which we know from the two letters she wrote. People described her as a "Comely Grave Woman" and "of a goodly Personage." She was also said to have a "piercing knowledge" and a "wonderful sweet and pleasant discourse."

Mary and William Dyer were Puritans. They wanted to make the Church of England simpler. They felt it still had too many parts from Roman Catholicism. Many Puritans moved to New England to practice their religion freely.

Moving to Massachusetts

In 1635, Mary and William Dyer sailed from England to New England. Mary was likely pregnant during the trip. Their son Samuel was baptized in Boston in December 1635. William Dyer became a "freeman" of Boston the next year. This meant he could vote and hold office.

Starting Rhode Island

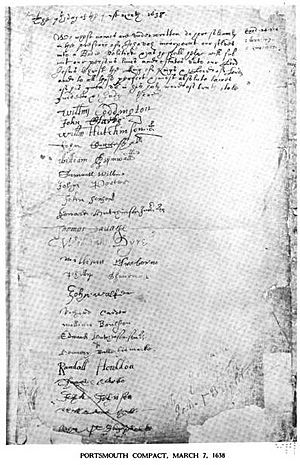

Many people who disagreed with the Boston leaders left Massachusetts. They bought land from Native Americans near Providence. In March 1638, a group of men, including William Dyer, signed an agreement for a new government. This group included many who supported Anne Hutchinson. They started their colony on Aquidneck Island (Rhode Island). They named their first settlement Pocasset.

William and Mary Dyer joined Anne Hutchinson and others in building this new place. After a year, some leaders disagreed. The Dyers moved to the south end of the island and started the town of Newport. William Dyer became the recording secretary for Newport.

Later, all four settlements in the area (Providence, Warwick, Portsmouth, and Newport) united. William Dyer was elected the General Recorder for the whole colony in 1648.

In 1651, William Coddington, a leader, went to England. He got permission to be governor-for-life of the island. Many people were unhappy about this. So, Roger Williams, John Clarke, and William Dyer went to England. They wanted Coddington's power taken away. Mary Dyer had already sailed to England before them. It's a mystery why she left her six children, including a baby, behind.

In England, the three men successfully had Coddington's power removed. William Dyer returned to Rhode Island with the good news. Mary, however, stayed in England for four more years.

Becoming a Quaker

In England

Mary Dyer stayed in England for over five years. During this time, she became very interested in Quakerism. Quakers are also known as the Society of Friends. They did not practice water baptism or the Lord's Supper. They also did not believe in having special ministers. Both women and men could preach and lead spiritual matters.

Quakers believed in freedom of conscience. They wanted the church and government to be separate. They met in silence, and anyone could speak if they felt inspired. They refused to bow to social superiors or take oaths. They also would not fight in wars. Puritans in Massachusetts saw Quakers as very dangerous. They passed many laws against them.

It's believed Mary Dyer became a Quaker minister in England. However, there are no clear records from that time to prove it. It's more likely she became a Quaker late in her stay. She probably started her ministry after returning to New England.

Quakers in Massachusetts

Massachusetts was the harshest colony in punishing Quakers. Other colonies like Plymouth and Connecticut also treated them badly. When the first Quakers arrived in Boston in 1656, there were no laws against them yet. But laws were quickly made, and punishments followed. Ministers and leaders strongly opposed Quakers.

The punishments for Quakers became more severe. This was the situation Mary Dyer returned to from England.

Mary Dyer's Return

In early 1657, Mary Dyer came back to New England. She was with Ann Burden, a widow. Mary was quickly recognized as a Quaker and put in jail. Her husband had to come to Boston to get her out. He promised she would not stay in Massachusetts or talk to anyone while leaving.

But Mary continued to travel and preach her Quaker message. In 1658, she was arrested in the New Haven Colony. She was then forced to leave for preaching her beliefs. She taught about the "inner light" and that women and men were equal in church.

In June 1658, two Quaker activists, Christopher Holder and John Copeland, came to Boston. They were already causing trouble for the leaders. They were joined by John Rous and put in prison. Mary Dyer heard about this while visiting friends in Providence. She, along with Mrs. Scott and her two daughters, went to Boston to visit the jailed men. All four women and the child were also imprisoned.

The Quaker situation was becoming a big problem for the leaders. They decided to make tougher laws. On October 19, 1658, a new law was passed in Massachusetts. It said Quakers would be banished from the colony. If they returned, they would be hanged. Mary Dyer, along with others, was sentenced to "banishment upon pain of death." Mary went home to Newport.

In June 1659, two Quakers, William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson, were arrested again. When Mary heard this, she left her home in Newport. She returned to Boston to support her Quaker friends. She was put in jail again. Her husband had written a long letter to the leaders. He questioned if their actions were legal.

On October 19, Mary, Robinson, and Stephenson were brought before Governor Endicott. They explained their mission from God. The governor then sentenced them to death. Mary replied, "The will of the Lord be done." When told to be taken away, she said, "Yea, and joyfully I go."

First Quaker Executions

The execution date for William Robinson, Marmaduke Stephenson, and Mary Dyer was October 27, 1659. Soldiers escorted them to the gallows. Mary walked hand-in-hand between the two men. When asked about this, she said, "It is an hour of the greatest joy I can enjoy in this world." The prisoners tried to speak to the crowd, but drums drowned out their voices.

William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson were executed. But as Mary waited, a pardon was announced. A request from her son, William, gave the leaders an excuse to stop her execution. It was a plan to scare Mary and make her give up. But Mary only expected to die as a martyr.

The next day, she wrote a letter to the General Court. She refused to accept the pardon. She was determined to die if the anti-Quaker laws were not changed.

After going home to Rhode Island, Mary spent the winter on Shelter Island. This island was a safe place for Quakers escaping Puritans. Here, Mary thought about the Puritans' explanation for their actions. She saw it as a way to calm public anger. She decided to return to Boston. She wanted to force the leaders to either change their laws or execute a woman. She left Shelter Island in April 1660, focused on this goal.

Mary Dyer's Martyrdom

Mary Dyer returned to Boston on May 21, 1660. Ten days later, she was again brought before the governor.

The governor asked if she was a prophetess. She answered that she spoke words the Lord gave her. When she started to speak again, the governor shouted, "Away with her! Away with her!" She was sent back to jail. Her husband had written a letter asking for her freedom, but no second pardon was given.

Execution

On June 1, 1660, at nine in the morning, Mary Dyer left the jail. She was escorted to the gallows. Once she was on the ladder under the elm tree, she was given a chance to save her life. She replied, "Nay, I cannot; for in obedience to the will of the Lord God I came, and in his will I abide faithful to the death."

The military leader, Captain John Webb, read the charges against her. He said she "was guilty of her own blood." Mary Dyer replied:

Nay, I came to keep bloodguiltiness from you, desiring you to repeal the unrighteous and unjust law of banishment upon pain of death, made against the innocent servants of the Lord, therefore my blood will be required at your hands who willfully do it; but for those that do is in the simplicity of their hearts, I do desire the Lord to forgive them. I came to do the will of my Father, and in obedience to his will I stand even to the death.

Her former pastor, John Wilson, urged her to change her mind. He told her not to be "so deluded and carried away by the deceit of the devil." To this, she answered, "Nay, man, I am not now to repent." When asked if she wanted the elders to pray for her, she said, "I know never an Elder here."

Burial

Records from Portsmouth, Rhode Island, state that Mary Dyer was "put to death at the Town of Boston... and there buried upon ye 31 day of ye 3d mo. 1660." The date is off by one day, as she died on June 1. It's unlikely she was buried in Boston. Evidence suggests she was buried on the Dyer family farm in Middletown, Rhode Island. It makes sense that her family would want her remains near them.

What Happened Next

After Mary Dyer's hanging, one of the officers, Edward Wanton, was so moved that he became a Quaker. His family later became important Quaker leaders in Rhode Island.

News of Mary's hanging spread quickly. But there was no immediate response from England. This was because of political changes there, with King Charles II returning to power. One more Quaker, William Leddra, was hanged in March 1661.

A few months later, a Quaker activist named Edward Burrough met with the king. The king then ordered that executions and imprisonments of Quakers must stop. He said any Quaker who broke laws should be sent to England for trial.

While the king's order stopped executions, Puritans still found ways to mistreat Quakers. By the 1670s, public opinion and royal orders finally ended the persecution of Quakers.

Mary Dyer's Legacy

Mary Dyer's life shows how a woman could stand up against powerful control. Her letters show her thoughts and reasons. Her actions can be seen as a public display of women's strength and belief. Quaker women were allowed to preach, and they felt they were acting under God's power.

Mary Dyer was very determined in her dealings with the leaders. She chose to become a martyr. She took full responsibility for her actions. She also asked the Puritan leaders to take moral responsibility for her death. Unlike Anne Hutchinson, Mary Dyer seemed to fully understand what would happen. Even though some called her "mad," her letters show she was very clear about her purpose.

When she was questioned, Mary used "yeas" and "nays." She refused to let others define her. She rejected being called a sinner. She also challenged the authority of the church elders.

Mary Dyer's story also shows strong loyalty. She became known when she walked out of the meeting house holding Anne Hutchinson's hand. Two decades later, she chose to stand by her Quaker friends and share their fate. She wrote that her life was "bound up" with her "dear Brethren and Seed" (fellow Quakers).

The Puritans found it strange that Mary walked hand-in-hand with two men to the gallows. But for Quakers, spiritual bonds were very strong. These bonds went beyond gender, age, and social class. This closeness was seen as a threat by the Puritans.

In her first letter, Mary Dyer compared her actions to the Book of Esther. Esther, a Jew, saved her people from a wicked man who wanted them killed. Mary saw herself as Esther, the Massachusetts leaders as the wicked man, and the Quakers as the Jews.

Mary Dyer's martyrdom did have an effect. Her story became a Quaker story. It was quickly shared in England and reached King Charles II. The king ordered an end to the death penalty for Quakers.

Mary Dyer's journey changed her from a silenced person to someone who spoke out. From a "monster" to a "martyr." Her death was a spiritual victory as much as it was a sad injustice.

Memorials and Honors

A statue honoring Mary Dyer was placed outside the Massachusetts State House in June 1959.

A bronze statue of Dyer, made by Quaker artist Sylvia Shaw Judson, stands in front of the Massachusetts State House in Boston. You can also find copies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Richmond, Indiana.

In Portsmouth, Rhode Island, Mary Dyer and Anne Hutchinson are remembered. There is an Anne Hutchinson/Mary Dyer Memorial Herb Garden at Founders' Brook Park. This garden has medicinal plants and a historical marker.

Mary Dyer was added to the Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame in 1997. She was also inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 2000.

Books and Plays

Several books have been written about Mary Dyer for adults. A biography for middle school students, Mary Dyer, Friend of Freedom by John Briggs, was published in 2014.

Mary Dyer herself did not publish books. But she wrote two important letters that are still kept today. These letters are central to her story as a martyr.

A play called Heretic, by Jeanmarie Simpson, is about Mary Dyer's life. She was also featured in Rachel Dyer, a novel from 1828 by John Neal. This book connects her story to the Salem witch trials.

Children and Family

Mary Dyer had eight known children. Six of them grew up. After she died, her husband remarried and had at least one more child.

- Her first child, William, was baptized in London in 1634 but died three days later.

- Her second child, Samuel, was baptized in Boston in 1635. He married Anne Hutchinson, the granddaughter of William and Anne Hutchinson.

- Her third child was a stillborn girl in 1637.

- Henry, born around 1640, was her fourth child.

- The fifth child was another William, born around 1642.

- Child number six was a boy named Mahershallalhashbaz.

- Mary was the seventh child, born around 1647.

- Mary Dyer's youngest child was Charles, born around 1650.

There is no proof that Mary's husband, William Dyer, ever became a Quaker.

Famous people who are descendants of Mary Dyer include Rhode Island Governors Elisha Dyer and Elisha Dyer, Jr.. Also, U.S. Senator from Rhode Island, Jonathan Chace.

See also

In Spanish: Mary Dyer para niños

In Spanish: Mary Dyer para niños

- Christian egalitarianism

- Christian views about women

- List of early settlers of Rhode Island

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |