John Clarke (Baptist minister) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Clarke

|

|

|---|---|

The Unknown Clergyman

(possible portrait of Clarke) |

|

| 3rd and 5th Deputy Governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | |

| In office 1669–1670 |

|

| Governor | Benedict Arnold |

| Preceded by | Nicholas Easton |

| Succeeded by | Nicholas Easton |

| In office 1671–1673 |

|

| Governor | Benedict Arnold |

| Preceded by | Nicholas Easton |

| Succeeded by | John Cranston |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Baptized 8 October 1609 Westhorpe, Suffolk, England |

| Died | 20 April 1676 (aged 66) Newport, Rhode Island |

| Resting place | Clarke Cemetery, Dr. Wheatland Blvd., Newport |

| Spouses | (1) Elizabeth Harris (2) Jane (_____) Fletcher (3) Sarah (_____) Davis |

| Occupation | Physician, Baptist Minister, Colonial agent, Deputy, Deputy Governor |

John Clarke (born October 1609, died April 20, 1676) was a doctor and a Baptist minister. He helped start the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He also wrote an important document called the Rhode Island Royal Charter, which gave people religious freedom in America.

John Clarke was born in Westhorpe, England. He studied a lot, earning a master's degree and becoming a doctor in Holland. He came to America in 1637 during a big religious disagreement. He decided to move to Aquidneck Island with others who were leaving the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

He helped found the towns of Portsmouth and Newport, Rhode Island. He also started America's second Baptist church in Newport. Baptists were not allowed in Massachusetts. Clarke even went to jail in Boston for trying to share his beliefs there.

After his time in prison, he went to England. There, he wrote a book about how Baptists were treated in Massachusetts. He also stayed in England for over ten years. He worked as an agent for the new Rhode Island colony, looking after its interests.

Other colonies like Massachusetts and Connecticut were not friendly to Rhode Island. They even tried to take some of Rhode Island's land. When King Charles II became king again in England in 1660, Rhode Island needed a special paper called a royal charter. This charter would protect its land and its people.

Clarke's job was to get this important paper. He saw it as a chance to include religious freedoms that no other charter had ever had. He sent many letters to King Charles II. He also spent months talking with Connecticut about land borders.

Finally, Clarke wrote the Rhode Island Royal Charter himself. King Charles II approved it on July 8, 1663. This charter gave amazing freedom and religious liberty to people in Rhode Island. It lasted for 180 years, making it the longest-lasting constitutional paper in history.

Clarke returned to Rhode Island after his success. He became very active in the colony's government. He also continued to lead his church in Newport until he died in 1676. He left a will that created the first educational trust fund in America. He strongly believed in "soul-liberty," which means people should be free to believe what they want. This idea was in the Rhode Island charter and later in the United States Constitution.

Contents

Early Life and Education

John Clarke was born in Westhorpe, Suffolk, England. He was baptized on October 8, 1609. He was one of seven children. Six of his siblings also moved from England to New England. We don't know much about his early life in England.

Clarke was very well educated. He arrived in New England at age 28 as both a doctor and a Baptist minister. His studies are clear from a book he wrote in 1652. They are also clear from how well he wrote the Rhode Island Royal Charter in 1663. His will even mentions his Hebrew and Greek books.

It is hard to trace Clarke's life in England because his name was very common. Some historians think he went to St Catharine's College, Cambridge. He might also have earned degrees from Brasenose College, Oxford. He likely studied medicine at Leiden University in Holland. Records show a "Johannes Clarcq, Anglus" (John Clark, England) graduated there in 1635.

Starting Rhode Island

Clarke arrived in Boston in November 1637. The colony was having a big religious and political problem. This problem was called the Antinomian Controversy. Many people were leaving Massachusetts Bay Colony because of it.

Some people went north to start a town in New Hampshire. A larger group didn't know where to go. They asked Roger Williams, who had started Providence Plantations. He suggested they buy land from the Narragansett people near his settlement.

Clarke joined a group of men in Boston on March 7, 1638. They wrote an agreement called the Portsmouth Compact. Some historians believe Clarke wrote it.

Twenty-three men signed it to form a government based on Christian ideas.

Roger Williams suggested two places for the group to settle. Clarke led a small group to Plymouth Colony to ask about land claims. He learned that Aquidneck Island was not claimed by Plymouth. This was good for Clarke, who wanted the settlers to be "clear of all, and be ourselves."

The settlers bought Aquidneck Island from the Narragansett leaders, Canonicus and Miantonomoh. Roger Williams helped with the deed. Many settlers' names were on the deed.

Clarke joined Anne Hutchinson and others to build a new settlement called Pocasset on Aquidneck Island. But after a year, there were disagreements among the leaders. Clarke joined William Coddington and others to move to the south end of the island. They started the town of Newport.

In 1640, Portsmouth and Newport joined together. Coddington was chosen as governor. Roger Williams wanted the settlements to be recognized by the king. He also wanted protection from Massachusetts, Plymouth, and Connecticut. In 1643, he went to England to get a patent for all four towns.

Coddington did not like this patent because the island towns were doing better than the mainland towns. He kept the island towns separate for a while. But in 1647, all four towns finally joined. They became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

Clarke had some legal training. Historians believe he wrote the first full set of laws for the colony in 1647. One historian called these laws a "model of legislation."

Starting the Newport Church

In 1638, Roger Williams started a church in Providence. It is now called the First Baptist Church in America. John Clarke started the next Baptist church on Aquidneck Island. It likely began when he arrived in 1638.

Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop wrote that there were Baptists on the island by 1640. A lawyer named Thomas Lechford said Clarke was the leader of a church there in 1640. Clarke led public worship in Newport from his arrival until 1644. That's when the church was officially founded.

The church is still active today. It is called the United Baptist Church, John Clarke Memorial. It honors its founder, John Clarke.

Standing Up for Baptist Beliefs

In 1649, Clarke went to Seekonk to help start a Baptist church. Roger Williams wrote that many people there were joining Clarke. They were getting baptized by immersion, which means being fully dipped in water. Williams believed this practice was closer to what Jesus did.

Some people in Seekonk had left their old church. They disagreed about infant baptism. Clarke and another man went to welcome them. They baptized them by immersion. One of these men was Obadiah Holmes.

The leaders in Massachusetts were angry about these baptisms. They believed it made earlier baptisms invalid. They also thought it made the ministers who performed them invalid. The Massachusetts leaders wrote to Plymouth, saying they should do something. Holmes later moved to Newport.

Imprisonment for Faith

In July 1651, Clarke, Obadiah Holmes, and John Crandall visited an elderly blind man named William Witter in Lynn, Massachusetts. Witter was a Baptist and too sick to travel. They held a religious service at his home.

During the service, two police officers arrived. They had a warrant to arrest Clarke and his friends. The warrant suggested they were arrested for baptizing people, even though they hadn't. The men were forced to attend a Puritan church service. They refused to take off their hats inside the church. Clarke explained why they did this at the end of the service.

The men were held that night. The next day, they were brought before local leaders. They were then taken to Boston. Clarke held another service at Witter's house, and Holmes baptized three people.

The prisoners were taken to Boston on July 22. Their trial was on July 31. They were questioned by Governor John Endicott. They were accused of being Baptists. Clarke said he was not against infant baptism, but he also didn't support it. The governor said the men "deserved death." He did not want "such trash" in his colony.

During the trial, the court accused them of several things. These included holding an unauthorized meeting and not removing their hats in church. They were also accused of saying Massachusetts churches were not true churches. The men were sentenced without anyone speaking against them.

Holmes was fined £30, Clarke £20, and Crandall £5. Holmes got the highest fine. Clarke protested the fines. He wrote a letter from prison, asking for a debate with the Puritan ministers. His fine was paid by friends without his knowledge, and he was released. He tried two more times to debate, but it never happened. Clarke had written down four main points of his beliefs.

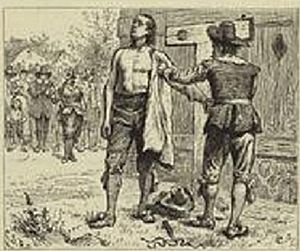

Friends paid the fines for Clarke and Crandall. But Holmes refused to let his fine be paid. He believed it was wrong. So, on September 5, 1651, Holmes was whipped 30 times in Boston. He later said he felt no pain. He told the leaders, "You have struck me as with roses."

What Happened Next

After the men's arrest, a man named Sir Richard Saltonstall wrote from England. He told the Boston church leaders that their "rigid ways" had made people dislike them. Roger Williams also wrote to Governor Endicott. He asked for religious tolerance, but his request was ignored.

Williams then wrote a book called The Bloody Tenent Yet More Bloody (1652). He used Clarke and Holmes's story in his book. He gave a copy to Clarke, writing that Clarke was a "witness of Christ Jesus against the bloody Doctrine of persecution."

One good thing came from this event. Some people who saw what happened changed their beliefs. One was Henry Dunster, the first president of Harvard College. His change in faith led to him losing his job in 1654. But it also helped start the First Baptist Church of Boston.

Some historians think Clarke planned this trip to make Massachusetts officials angry. This would help Rhode Island's cause in England. Soon after arriving in England, Clarke published Ill Newes from New-England. This book described what happened with the Massachusetts authorities. It asked the king for religious tolerance. The book helped shape public opinion and gain support for Rhode Island's charter.

Time in England

William Coddington was not happy with the patent Roger Williams got in 1643. He did not want the four settlements to join into one Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He wanted the two island towns, Newport and Portsmouth, to be independent. So, he went to England to make his case.

On April 3, 1651, Coddington was given power to govern the islands of Aquidneck and Conanicut for life.

Ending Coddington's Rule

People in Rhode Island were upset when Coddington returned with his new power. Clarke spoke out against Coddington's rule. He was chosen to be the island's agent to England on October 15, 1651. The next month, he and William Dyer were sent to England. Their goal was to get Coddington's power taken away.

At the same time, the mainland towns sent Roger Williams on a similar mission. The three men sailed for England in November 1651. This was just a few months after Clarke was released from prison.

Coddington's power over the island government was removed in October 1652. Henry Vane helped with this. William Dyer returned to Rhode Island with the news. But Clarke stayed in England with his wife.

Ill Newes from New England

Soon after arriving in England, Clarke published his book, Ill Newes from New England: or a Narrative of New England's Persecution (1652). The book began with a letter to the English Parliament. It asked for freedom of conscience and religious tolerance. Then came a letter to the Puritan leaders in Massachusetts.

Most of the book explained Clarke's beliefs about how a church should be run. He explained why he thought the Massachusetts churches were wrong. Less than half of the book was about the persecution he and his friends faced. He wrote that no one should control another person's conscience. He said conscience is a "sparkling beam" that cannot be forced.

The book worked. The Massachusetts leaders were so worried about Ill Newes that a minister wrote a book to argue against it. This book defended using force to keep the "correct" church in Massachusetts. But it actually confirmed the persecutions Clarke wrote about. This helped Rhode Island gain important religious freedoms. One historian called Clarke "the Baptist drum major for freedom in seventeenth century America."

Rhode Island's Agent

Clarke was Rhode Island's official agent in England. He did not get much money for his work. But he stayed active in his religious beliefs. He joined a Baptist church in London. He preached there, which helped him with money and a place to stay. He also worked as a lawyer and doctor in London.

Clarke spent most of his time in England during a period when Parliament ruled the country. His main goal was to get a stronger charter for Rhode Island. This charter would protect the religious freedoms the colony was founded on. The leader of England, Oliver Cromwell, confirmed Rhode Island's 1643 patent. Clarke also helped the colony by sending supplies like gunpowder.

Clarke became friends with Richard Baily in London. Baily helped him with legal advice and writing letters to the king. He might have even helped Clarke write Rhode Island's charter. When Clarke finally went back to Newport, Baily sailed with him.

Getting a Royal Charter

In 1660, Charles II became king of England. He passed a law that made everyone follow the Anglican Church. This made it harder for Clarke to get a charter that included religious freedoms. Clarke's job as agent for Rhode Island was renewed in October 1660. He sent at least ten letters to the king between 1661 and 1662. He promised the king Rhode Island's loyalty. Then he asked for the king's support to guarantee freedom of conscience in religion.

Clarke wrote a very powerful request in a letter to the king on February 5, 1661. He asked for a "LIVELY EXPERIMENT" that a successful government could exist "WITH A FULL LIBERTIE IN RELIGIOUS CONCERNMENTS." These words became a symbol of Rhode Island's fight for religious freedom. They were later included in the charter itself. They are even carved on the Rhode Island State House.

A problem came up in 1662. The governor of Connecticut, John Winthrop, Jr., met with the king before Clarke. He got a new charter for his colony. Winthrop was friendly with many Rhode Islanders. But he also had land interests that went against Rhode Island's claims. Clarke thought Winthrop's actions were unfair. Winthrop avoided Clarke in England.

The Earl of Clarendon saw the conflict between Connecticut and Rhode Island. He called Winthrop and Clarke to meet in July 1662. He wanted to settle the land dispute between the two colonies. Both colonies claimed land between the Pawcatuck River and the Narragansett Bay. After months of talks, the border was set at the Pawcatuck River. People who lived on the disputed land could choose which colony to be part of. Once this was settled, Winthrop went back to New England. Clarke then made his final push for Rhode Island's charter.

After all the arguments about land, the other parts of the charter were easily approved. Many parts of Rhode Island's charter were like Connecticut's. But Rhode Island wanted more self-government. And the Rhode Island charter went much further in guaranteeing religious freedom.

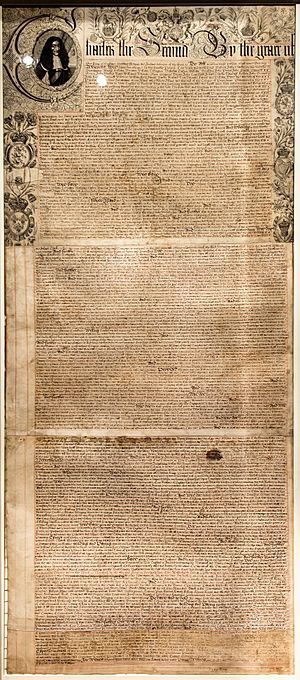

Rhode Island's Royal Charter

Once the border issue was fixed, the charter, written by Clarke, was approved by the king on July 8, 1663. This document was amazing. It gave Rhode Island a lot of power to govern itself. It also gave religious freedom like never before. The charter's rules were so strong that Rhode Island became very independent. The document lasted for 180 years.

The charter set the colony's borders. It also made rules for a military and for fighting wars. It protected fishing rights. It also explained how to appeal to England if there were problems. The charter made sure Rhode Islanders could travel freely in other colonies. Before, their travel was sometimes stopped for religious reasons.

The new charter also stopped other New England colonies from fighting Native Americans within Rhode Island without its permission. It also said that arguments with other colonies would be sent to the king. It also set up the colony's government. This included a governor, deputy governor, and ten assistants. It also said how many representatives each town would have.

The most important part for Clarke was the charter's clear promise of religious freedom. It said Rhode Islanders did not have to follow the Anglican Church. This was "because some of the people ... cannot, in their private Opinions, conform to the publique exercise of religion." It also said:

that no person within the said colony, at any time hereafter shall be any wise molested [harassed], punished, disquieted, or called in question, for any differences in opinion in matters of religion, and do not actually disturb the civil peace of our said colony; but that all and every person and persons may, from time to time, and at all times hereafter, freely and fully have and enjoy his and their own judgments and consciences, in matters of religious concernments, throughout the tract of land hereafter mentioned, they behaving themselves peaceable and quietly ...

Once Clarke had the charter, he needed to send it to Rhode Island. But he had not been paid much for his work. He did not have money to sail back right away. So, he gave the charter to Captain George Baxter. Baxter carried it to Rhode Island.

On November 24, 1663, Rhode Island's General Court met in Newport. They gathered to officially receive the charter. This was the result of Clarke's ten years of hard work. The event was very important. The colonial records describe it:

At a very great meeting and assembly of the freemen of the colony of Providence Plantation, at Newport, in Rhode Island, in New England, November the 24th, 1663. The abovesayed Assembly being legally called and orderly mett for the sollome reception of his Majestyes gratious letter pattent unto them sent, and having in order thereto chosen the President, Benedict Arnold, Moderator of the Assembly, [it was] Voted: That the box in which the King's gratious letters were enclosed be opened, and the letters with the broad seale thereto affixed be taken forth and read by Captayne George Baxter in the audience and view of all the people; which was accordingly done, and the sayd letters with his Majesty's Royall Stampe, and the broad seal, with much becoming gravity held up on hygh, and presented to the perfect view of the people, and then returned into the box and locked up by the Governor, in order to the safe keeping of it.

The next day, they voted to thank the King and the Earl of Clarendon. They also voted to give Clarke £100. The charter worked well for a long time. It was not replaced until 1843, 180 years later. It was replaced only because the way representatives were chosen was no longer fair. When it was finally retired, it was the longest-lasting constitutional charter in the world. It was so strong that even the American Revolutionary War did not change it. This is because both the revolution and the charter were based on the same idea: the right to govern oneself.

Later Life and Impact

With the royal charter on its way to New England, Clarke needed to find money to get himself back. A week after the king approved the charter, Clarke mortgaged his Newport properties. But he still could not leave England right away. He and his wife finally sailed back to Rhode Island the next spring. They carried their belongings and weapons for the colony.

Even with the great charter, land disputes with Connecticut continued for over 50 years. There were also problems with the Atherton Company, which owned land within Rhode Island. Luckily for Rhode Island, a group of royal commissioners arrived in 1664. They confirmed that the Narragansett people had submitted to the English king in 1644.

The commissioners then declared all the Narragansett territory to be Kings Province. This included the Atherton lands. One commissioner was Samuel Maverick, a friend of Rhode Island's governor. He disliked the Atherton Company. Clarke was one of three men who presented Rhode Island's views on the land disputes. The commissioners strongly supported Rhode Island. Eventually, the Atherton Company lost its land. Kings Province became part of the Rhode Island colony.

Government Roles

After his important work in England, Clarke became even more involved in Rhode Island's government. He served for six years as a Deputy from Newport in the General Assembly. He then served as Deputy Governor under Governor Benedict Arnold for two years.

Because of his legal knowledge, he was asked to organize Rhode Island's laws in 1666. In 1670 and 1672, he was chosen to go back to England as an agent for the colony. In 1672, he was supposed to appeal to the king because Connecticut was taking Rhode Island's land. But the plan to send him was canceled.

From 1675 to 1676, Rhode Island was caught in King Philip's War. This was a very destructive conflict in New England. It ruined many towns on the mainland. This war was between Native Americans and English settlers. It was named after Metacomet, a Native American leader called King Philip by the English.

Rhode Island was more peaceful with Native Americans than other colonies. But because of its location, it suffered a lot of damage. Warwick and Pawtuxet were completely destroyed. Much of Providence was also ruined. Clarke was highly respected in the colony. He was one of 16 leaders whose advice was sought during the war. Two weeks later, while the war was still happening, Clarke died.

Church Issues

When Clarke returned from England, he also continued to lead the Newport church. There were two major disagreements in the church. One happened while he was in England. The other happened several years after he returned.

The first disagreement was about "laying on of hands." This was a practice some believed was important. Some church members wanted it to be required. Others did not want more rules. This led to William Vaughan leaving the church in 1656. He formed his own Baptist church in Newport.

The second disagreement was about the day of worship. Some members wanted to worship on Saturday, like Sabbatarians. This was mostly allowed. But the elder Obadiah Holmes did not like this practice. Clarke told Holmes to be less harsh in 1667. Holmes stopped preaching at the Newport church for a while. But he started again in 1671. When he continued to criticize the Sabbatarians, they left to form their own church in December 1671.

More disagreements happened in the church. A family named Slocum was involved. When Joan Slocum said she did not believe Christ was alive, she was removed from the church in 1673. Her husband, children, and their spouses then left the church. They became Quakers.

Death and Lasting Impact

John Clarke wrote his will on April 20, 1676. He died in Newport the same day. He was buried in his family plot in Newport, next to his first two wives, Elizabeth and Jane.

In his will, he created a trust. This trust was "for the relief of the poor or bringing up of children unto learning from time to time forever." This trust is still used today. It is thought to be the oldest educational trust fund in the United States.

Clarke believed that government and religion should exist peacefully side-by-side. He was a key figure in the idea of separation of church and state. Historian Thomas Bicknell said that when the Puritans settled New England, civil and religious freedom did not exist anywhere else. He said it was first clearly established in Rhode Island, led by John Clarke.

Another historian, Louis Asher, wrote that Clarke was the first to bring democracy to the New World through Rhode Island. Bicknell also said Clarke was the "recognized founder and father" of the Aquidneck Plantations. He called him the "leading spirit" in organizing the island towns. Historian Edward Peterson wrote that Clarke was a man "whose moral character has never been surpassed." Asher said that Clarke "lived for others." He gave more to his fellow humans than he received.

The First Baptist Church of Newport, a grammar school, and a ship called the SS John Clarke are named after him. The Physical Sciences building at Rhode Island College was dedicated in his honor in 1963. A plaque at the Newport Historical Society reads:

Erected by the Newport Medical Society

December 1885

To

John Clarke, Physician

1609–1676

Founder of Newport

And of the Civil Polity of Rhode Island

Family History

John Clarke was the fifth of seven children born to Thomas and Rose Clarke. All were born or baptized in Westhorpe, Suffolk, England. His older siblings were Margaret, Carew, Thomas, and Mary. His younger brothers were William and Joseph. Margaret lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Mary came to Newport, Rhode Island, with her husband and four brothers.

John Clarke was married three times. His first wife was Elizabeth Harris. She was with him while he was an agent in England. She died in Newport a few years before Clarke. After her death, he married Jane Fletcher in 1671. She died the next year. Clarke had a daughter with Jane, but she died young.

Clarke's third wife was Sarah Davis. She was the widow of Nicholas Davis. Davis had been an early settler of Aquidneck Island. He later became a merchant and moved to Plymouth Colony. Davis became a Quaker. He was imprisoned and banished from Massachusetts in 1659. He later lived in Newport. He helped the Quaker founder George Fox travel in 1672. Davis drowned soon after. Within a year and a half, his widow Sarah married Clarke. Sarah outlived Clarke and died around 1692. She had children who were mentioned in Clarke's will.

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |