George Fox facts for kids

Quick facts for kids George Fox |

|

|---|---|

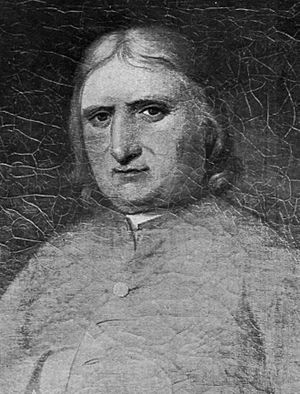

A supposed portrait of Fox from the 17th century

|

|

| Church | Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 1624 Drayton-in-the-Clay, Leicestershire, England |

| Died | 13 January 1691 (aged 66) London, England |

| Buried | Quaker Gardens, Islington |

| Denomination | Quaker |

| Parents | Christopher Fox (father) and Mary Lago (mother) |

| Spouse | Margaret Fell (née Askew) |

| Occupation | Founder and religious leader of Quakers |

| Signature |  |

George Fox (July 1624 – 13 January 1691) was an English religious leader. He was a founder of the Religious Society of Friends, often called the Quakers. George Fox was the son of a Leicestershire weaver. He lived during a time of big changes and wars in England.

Fox challenged the religious and political leaders of his time. He offered a new way to follow the Christian faith. He traveled all over Britain, sharing his ideas. He also performed many healings. Because of his beliefs, he was often treated badly by the authorities. In 1669, he married Margaret Fell. She was a wealthy supporter and a key leader among the Friends. Fox's work grew, and he traveled to North America and the Netherlands. He was put in jail many times for his beliefs. In his last years, he worked in London to organize the growing Quaker movement. Even though some Anglicans and Puritans disliked him, important people like William Penn and Oliver Cromwell respected him.

Contents

Early Life of George Fox

George Fox was born in Drayton-in-the-Clay, Leicestershire, England. This village was very Puritan. It is now called Fenny Drayton. He was the oldest of four children. His father, Christopher Fox, was a successful weaver. People called him "Righteous Christer." His mother was Mary Lago. Christopher Fox was a churchwarden and quite wealthy. He left George a good amount of money when he died.

From a young age, George was very serious and religious. He learned to read and write, but there is no record of him going to school. He said that by age eleven, he knew about "pureness and righteousness." He felt God taught him to be honest in everything. He also said, "The Lord taught me to be faithful in all things... and to keep to Yea and Nay in all things." This meant always telling the truth.

Fox's family thought he might become a priest. Instead, he became an apprentice to a local shoemaker and farmer named George Gee. This job suited his quiet nature. He became known for working hard among the wool traders. Fox always wanted to live a "simple" life. This meant being humble and not wanting fancy things. He spent a short time as a shepherd, which helped him form these ideas. He later wrote that many important Bible figures, like Moses and David, were shepherds. This showed that formal education was not needed for religious work.

As he grew up, Fox saw people who followed the Church of England. But by age 19, he disliked their behavior, especially their drinking. One night, after leaving friends at a drinking place, Fox felt an inner voice. It told him to leave behind all people, young and old, who lived in "vanity." He was to be like a stranger to them.

George Fox's First Travels

Fox felt a strong inner call. In September 1643, he left his home and traveled towards London. He felt troubled and confused. The English Civil War had started, and soldiers were in many towns. In Barnet, he felt very sad. He stayed in his room for days or walked alone in the countryside.

After almost a year, he went back home. He had long talks about religion with Nathaniel Stephens, the local clergyman. Stephens thought Fox was smart. But they disagreed so much that Stephens later called Fox crazy.

For the next few years, Fox kept traveling. His own religious ideas began to form. Sometimes he looked for help from clergy members. But he found no comfort from them. They did not seem to understand his problems. One advised him to use tobacco and sing psalms. Another got angry when Fox stepped on a flower. A third suggested bloodletting. Fox became very interested in the Bible. He studied it carefully.

He thought deeply about the Temptation of Christ. He felt his own spiritual journey was similar. He gained strength from believing that God would protect him. Through prayer and thinking, he understood his faith better. He called this process "opening." He also gained a deep understanding of Christian beliefs. Some of his main ideas were:

- Religious ceremonies are not needed if you have a true spiritual change inside.

- God's Holy Spirit gives people the ability to preach, not church schooling. This means anyone, even women and children, can preach if God guides them.

- God lives "in the hearts of his obedient people." This means religious experiences are not only in church buildings. Fox refused to call a building a "church." He called it a "steeple-house." Many Quakers still use this word. Fox would worship in fields and orchards. He believed God's presence could be felt anywhere.

- Fox used the Bible to support his views. But he believed that because God was inside believers, they could follow their own inner guide. They did not need to rely only on the Bible or what priests said.

- Fox also saw no clear difference between God the Father, Jesus the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

The Religious Society of Friends

In 1647, Fox began to preach in public. He spoke in market-places, fields, and sometimes even in "steeple-houses" after their services. His powerful preaching attracted a small group of followers. It is not clear exactly when the Society of Friends began. But soon, a group of people often traveled together. At first, they called themselves "Children of the Light" or "Friends of the Truth." Later, they were simply called "Friends."

Fox did not seem to want to start a new church at first. He only wanted to share what he saw as the true Christian ideas. But he later became a great organizer. He helped create the structure for the new society.

Many different Christian groups existed at that time. There was much debate and confusion. This gave Fox a chance to share his own beliefs. Fox's preaching was based on the Bible. But it was powerful because of his strong personal experience. He spoke strongly against bad behavior and unfair taxes. He urged people to live without sin. By 1651, he had other talented preachers with him. They continued to travel, even though some people treated them badly. They were sometimes whipped or beaten. As his fame grew, not everyone liked his words. He was a strong preacher and argued with those who disagreed with him.

Quaker worship, with silent waiting and people speaking when they felt God's Spirit, was common by this time. Speaking was an important part of their meetings from the very beginning.

Imprisonment of George Fox

Fox complained to judges about decisions he thought were wrong. For example, he wrote a letter about a woman who was to be executed for theft. He also spoke out against paying tithes. These were taxes meant to fund the official church. Fox believed the official church was not needed. He thought a university degree was not important for a preacher. This often led to problems with the government.

Fox was put in prison many times. The first time was in Nottingham in 1649. In Derby in 1650, he was jailed for speaking against accepted religious ideas. A judge made fun of Fox's words to "tremble at the word of the Lord." He called Fox and his followers "Quakers." Fox refused to fight in the army or for any reason. Because of this, his prison sentence was made longer. Refusing to swear oaths or fight became very important in his public statements. Quakers could be arrested for not swearing loyalty to the king. It also made it hard for them to speak in court. In a letter from 1652, he told Friends not to use "physical weapons" but "spiritual weapons."

In 1652, Fox preached for hours under a tree in Balby. His follower Thomas Aldham helped start the first Quaker meeting in that area. That same year, Fox felt God led him up Pendle Hill. There, he had a vision of many people coming to Christ. From there, he went to Sedbergh. He preached to over a thousand people on Firbank Fell. Many people, including Francis Howgill, believed that Christ could speak directly to people.

Later that month, he stayed at Swarthmoor Hall. This was the home of Thomas Fell and his wife, Margaret Fell. Thomas Fell was an important judge. Margaret became a Quaker. Thomas did not convert, but he knew the Friends well. This helped when Fox was arrested for speaking against accepted religious ideas in October. Fell was one of the judges, and the charges were dropped.

Fox stayed at Swarthmoor until the summer of 1653. Then he went to Carlisle, where he was arrested again. Some even wanted to put him to death. But Parliament asked for his release. They did not want "a young man... die for religion."

He was jailed again in London in 1654, Launceston in 1656, Lancaster in 1660, Leicester in 1662, Lancaster again and Scarborough from 1664–1666, and Worcester from 1673–1675. The charges usually included causing trouble and traveling without permission. Quakers broke laws against unauthorized worship. Also, their belief in equality meant they refused to use titles, take off their hats in court, or bow to those who thought they were better. This was seen as disrespectful. While in prison at Launceston, Fox wrote that Jesus said, "Swear not at all." He believed that people should just say "yes" or "no."

In prison, George Fox kept writing and preaching. He felt that being in jail helped him meet people who needed his help. These included jailers and other prisoners. In his journal, he told a judge that "God dwells not in temples made with hands." He also tried to set a good example. He would turn the other cheek when beaten. He refused to show his captors that he was sad.

Meetings with Oliver Cromwell

Government leaders became suspicious of groups like the Quakers. They feared that Fox's followers wanted to overthrow the government. By this time, his meetings often had over a thousand people. In early 1655, he was arrested in Whetstone, Leicestershire. He was taken to London with armed guards. In March, he met the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.

Fox told Cromwell he had no plans to fight. Then he spoke to Cromwell for most of the morning about the Friends. He advised Cromwell to listen to God's voice. As Fox left, Cromwell had tears in his eyes. He said, "Come again to my house." He added that he wished Fox no more harm than he did to himself.

This meeting later became an example of "speaking truth to power." This is a way Quakers try to influence powerful people. The idea is to speak simply and honestly to leaders. Quakers use this to try to stop war, unfairness, and oppression.

Fox asked Cromwell in 1656 to stop the persecution of Quakers. Later that year, they met a second time. They got along well, even though they disagreed. Fox asked Cromwell to "lay down his crown at the feet of Jesus." Cromwell did not do this. Fox met Cromwell two more times in March 1657. Their last meeting was in 1658. They could not talk long because Cromwell was very ill. Fox even wrote that Cromwell "looked like a dead man." Cromwell died in September of that year.

Challenges and Growth

The persecutions of these years were hard. About a thousand Friends were in prison by 1657. This made Fox's views on old religious and social practices stronger. In his preaching, he often stressed that Quakers did not use baptism by water. This showed how Quakers focused on inner change, not outward rituals. It also challenged others, giving Fox chances to argue about the Bible. The same happened in court. When a judge told him to take off his hat, Fox asked where the Bible said to do that.

The Society of Friends became more organized around this time. Large meetings were held. This included a three-day event in Bedfordshire. This was the start of the yearly meetings Quakers have today. Fox asked two Friends to travel and collect stories of imprisoned Quakers. This showed how they were being treated badly. This led to the creation of the Meeting for Sufferings in 1675. This group still exists today.

The 1650s were a very creative time for the Friends. Fox had hoped the movement would become the main church in England. But disagreements, persecution, and growing social problems made Fox very sad. He was deeply troubled for ten weeks in 1658 or 1659. In 1659, he sent parliament a strong pamphlet. It was called Fifty nine Particulars laid down for the Regulating things. But the year was too chaotic, and it was not considered.

The Restoration of the Monarchy

When the king returned to power, Fox's dream of Quakers becoming the main religion ended. He was again accused of plotting against Charles II. He was also called a fanatic, which he disliked. He was jailed in Lancaster for five months. While there, he wrote to the king. He advised Charles to avoid war and religious persecution. He also suggested stopping oath-taking, plays, and maypole games. These last ideas showed Fox's Puritan leanings. These ideas influenced Quakers for centuries. Fox was released again after showing he had no military plans.

Charles II did listen to Fox on one point. The 700 Quakers who had been jailed were released. But the government was still unsure about the Quakers. A revolt by another group in January 1661 led to more repression of non-Anglican groups, including Quakers. After this, Fox and eleven other Quakers made a public statement. It became known as the "peace testimony." They promised to oppose all wars and fighting. They believed this was against God's will. Not all his followers agreed with this. But persecution against Quakers continued.

Some Quakers, like John Perrot, were unhappy with Fox's growing power. Like others before them, they did not see why men should remove their hats for prayer. They argued that men and women should be treated equally. Perrot lost the argument. He moved to the New World. Fox kept his leadership of the movement.

Parliament passed laws that made non-Anglican religious meetings of more than five people illegal. This made Quaker meetings against the law. Fox told his followers to openly break these laws. Many Friends, including women and children, were jailed over the next 25 years. Meanwhile, Quakers in New England had been banned. Some were even executed. Charles was advised to stop this practice and allow them to return. Fox met some of the New England Friends in London. This made him interested in the colonies. Fox could not travel there right away. He was jailed again in 1664 for refusing to swear an oath. When he was released in 1666, he focused on organizing. He set up monthly and quarterly meetings across England and Ireland.

Visiting Ireland also gave him a chance to speak against what he saw as problems with the Roman Catholic Church. He especially disliked their use of rituals. Fox, raised in a Protestant environment, did not see any similarities between the two groups.

Fox married Margaret Fell of Swarthmoor Hall on October 27, 1669. She was from a high social class and was one of his early followers. She was ten years older than him and had eight children from her first husband, Thomas Fell. Margaret was very active in the Quaker movement. She worked for equality and for women to be accepted as preachers. Quaker weddings did not have priests. So, their marriage was a simple civil ceremony approved by them and the witnesses. Ten days after the wedding, Margaret went back to Swarthmoor to continue her work. George went back to London. Their shared religious work was central to their life together. They later worked together on much of the Society's organization. Soon after the marriage, Margaret was jailed in Lancaster. George stayed in the south of England. He became so sick and sad that he lost his sight for a time.

Travels in North America and Europe

By 1671, Fox had recovered, and Margaret was released by the King's order. Fox decided to visit the English settlements in North America and the West Indies. He stayed there for two years. After a seven-week journey, his group arrived in Barbados on October 3, 1671. From there, Fox sent a letter to Friends. It explained the role of women's meetings in Quaker weddings. This was a new idea in some places. He suggested that a meeting of only women should interview the couple before marriage. This was to check for any problems.

Fox wrote a letter to the governor of Barbados. He denied that Quakers were causing slaves to revolt. He also tried to confirm that Quaker beliefs were correct. After a stay in Jamaica, Fox landed in Maryland. He took part in a four-day meeting of local Quakers. He stayed there to meet some Native Americans who were interested in Quaker ways. He said they had "a great dispute" among themselves about joining the meeting. Fox was impressed by their polite and loving behavior. He did not like the idea that God's Spirit was not in the Native Americans. Fox rejected this idea. He did not write about meeting slaves on the mainland.

In other colonies, Fox helped set up Quaker organizations. These were similar to those in Britain. He also preached to many non-Quakers. Some of them became Quakers.

After traveling widely in the American colonies, George Fox returned to England in June 1673. He was confident that his movement was strong there. But back in England, he found his movement divided. Some Friends resisted the women's meetings and the power of those in London. With William Penn and Robert Barclay helping Fox, the challenge to his leadership was overcome. But during this time, Fox was jailed again. He refused to swear oaths after being caught in Armscote, Worcestershire. His mother died soon after hearing of his arrest. Fox's health began to suffer. Margaret Fell asked the king for his release, which was granted. But Fox felt too weak to travel right away.

While recovering at Swarthmoor, he began to dictate his journal. This was published after his death. He also wrote many letters, books, and essays. Much of his energy went to the topic of oaths. He believed it was very important to Quaker ideas. By refusing to swear, he felt he showed the importance of truth in daily life. He connected truth with God and the inner light.

For three months in 1677 and one month in 1684, Fox visited the Friends in the Netherlands. He organized their meetings there. The first trip was longer. He traveled into what is now Germany. Meanwhile, Fox was involved in a debate among Friends in Britain. This was about the role of women in meetings. This struggle took much of his energy and left him tired. Returning to England, he stayed in the south to try to end the dispute. He was interested in the founding of Pennsylvania. Penn had given him over 1,000 acres (4 km2) of land there. Persecution continued, and Fox was briefly arrested in October 1683. Fox's health was getting worse. But he kept working. He wrote to leaders in Poland, Denmark, Germany, and other places. He wrote about his beliefs and how Quakers were being treated.

Last Years of George Fox

In his last years, Fox continued to attend the London Meetings. He also kept asking Parliament to help the Friends who were suffering. The new King, James II, pardoned religious dissenters. These were people jailed for not attending the official church. This led to about 1,500 Friends being released. The Quakers lost some influence after the Glorious Revolution. But the Act of Toleration 1689 ended the laws that persecuted Quakers. It allowed them to meet freely.

George Fox died on January 13, 1691. This was two days after he preached at the Gracechurch Street Meeting House in London. He was buried three days later in the Quaker Burying Ground. Thousands of people attended his burial.

Book of Miracles

George Fox performed many healings during his time as a preacher. Records of these were collected in a special book called Book of Miracles. This book was listed in the Friends Library in London. In 1932, Henry Cadbury found a reference to it. The book was then put back together using this information and journal entries.

According to Rufus M. Jones, the Book of Miracles shows George Fox as a "remarkable healer of disease." It gave him a reputation as someone who could perform miracles. This book was purposely kept from being printed for a long time. Instead, Fox's Journal and other writings were published.

A short example from the Book of Miracles says: "And a young woman her mother... had made her well. And another young woman was... small pox... of God was made well."

Journal and Letters

Fox's journal was first published in 1694. It was edited by Thomas Ellwood, a friend of John Milton. William Penn wrote the introduction. Like many books from that time, the journal was not written as events happened. It was put together many years later, mostly by Fox dictating it. Some parts of the journal were not even written by Fox himself. They were put together by editors from different sources.

The journal mostly leaves out disagreements within the Quaker movement. It also does not mention how much others helped develop Quakerism. Fox shows himself as always being right. He also shows God always helping him. As a religious autobiography, it has been compared to famous works like Augustine's Confessions. It is a very personal book. It only becomes interesting to readers after a lot of editing. Historians use it as an important source. It has many details about everyday life in the 17th century. It also mentions the many towns and villages Fox visited.

Hundreds of Fox's letters were also published. Most were meant for many people to read. Some were private. They were written from the 1650s onward. Titles included Friends, seek the peace of all men and To Friends, to know one another in the light. These letters show a lot about Fox's beliefs. They also show his strong desire to share them. These writings, according to Henry Cadbury, a Quaker professor, "contain a few fresh phrases of his own, [but] are generally characterized by an excess of scriptural language and today they seem dull and repetitious." Others say that "Fox's sermons, rich in biblical metaphor and common speech, brought hope in a dark time." Fox's short, wise sayings were popular beyond the Quakers. Many other church groups used them to explain Christian ideas.

Ellwood described Fox as "graceful in countenance, manly in personage, grave in gesture, courteous in conversation." Penn said he was "civil beyond all forms of breeding." People said he was "plain and powerful in preaching, fervent in prayer." He was good at understanding others. He was also good at controlling himself. He knew how to "speak a word in due season to the conditions and capacities of most, especially to them that were weary, and wanted soul's rest." He was "valiant in asserting the truth, bold in defending it, patient in suffering for it, immovable as a rock."

Legacy of George Fox

Fox had a huge impact on the Society of Friends. His beliefs have largely continued to this day. Perhaps his most important achievement was his leadership. He helped the movement overcome challenges from the government after the king returned. He also helped solve internal disagreements that threatened the Quakers. Not all of his beliefs were liked by all Quakers. For example, his Puritan-like dislike of arts and formal religious study. This stopped Quakers from developing these practices for some time. The George Fox room at Friends House, London, UK, is named after him.

Walt Whitman, whose parents were inspired by Quaker ideas, later wrote: "George Fox stands for something too – a thought – the thought that wakes in silent hours – perhaps the deepest, most eternal thought latent in the human soul. This is the thought of God, merged in the thoughts of moral right and the immortality of identity. Great, great is this thought – aye, greater than all else."

George Fox is remembered in the Church of England with a special day on January 13.

|

See also

In Spanish: George Fox para niños

In Spanish: George Fox para niños

- Christian anarchism

- Christian mysticism

- George Fox University

- List of abolitionist forerunners

- List of people on stamps of Ireland

- Anthony Sharp (Quaker), Dublin Quaker and merchant

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |