Thomas Pownall facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Pownall

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the Great Britain Parliament for Minehead, Somerset |

|

| In office 1774–1780 Serving with John Fownes-Luttrell

|

|

| Preceded by | Henry Fownes-Luttrell |

| Succeeded by | Francis Fownes-Luttrell |

| Member of the Great Britain Parliament for Tregony, Cornwall |

|

| In office 1767–1774 Serving with Sir Abraham Hume and John Grey

|

|

| Preceded by | William Trevanion |

| Succeeded by | George Lane Parker |

| Governor of the Province of South Carolina | |

| In office 1760 – 1760,Resigned having never assumed office |

|

| Appointed by | Lords of Trade |

| 10th Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay | |

| In office 3 August 1757 – 3 June 1760 |

|

| Appointed by | Lords of Trade |

| Preceded by | Massachusetts Governor's Council (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Hutchinson (acting) |

| Lieutenant Governor of the Province of New Jersey | |

| In office 13 May 1755 – 23 September 1757 |

|

| Governor | Jonathan Belcher |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 25 February 1805 (aged 82) Bath, Somerset, England |

| Spouse | Harriet Fawkener |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Signature |  |

Thomas Pownall (born September 4, 1722 – February 25, 1805) was a British government official and politician. He served as the governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay from 1757 to 1760. Later, he was a member of the House of Commons, a part of the British Parliament, from 1767 to 1780.

Before the American Revolutionary War, Pownall traveled a lot in the American colonies. He disagreed with Parliament's attempts to tax the colonies. He was one of the few people in Britain who supported the colonists' views until the Revolution began.

Pownall had a good education and strong connections in London's colonial government. He first came to North America in 1753. He spent two years exploring the colonies. In 1755, he became the Lieutenant Governor of New Jersey.

He became governor of Massachusetts in 1757. He helped remove the previous governor, William Shirley. His time as governor was mainly focused on the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years' War). Pownall was very important in getting the Massachusetts militia ready for the war. He did not like the military interfering with colonial government. He also opposed forcing British soldiers to stay in private homes. He generally had a good relationship with the local assembly, which was like a colonial parliament.

After returning to England in 1760, Pownall remained interested in colonial matters. He wrote popular books about the colonies, including The Administration of the Colonies. As a Member of Parliament, he often spoke up for the colonies. He supported the war effort once the Revolutionary War started. Later in his life, he became an early supporter of reducing trade barriers. He also wanted Britain and the United States to have a strong relationship. Some writers have suggested that Pownall was "Junius," a secret writer who criticized the British government.

John Adams, a future U.S. president, once said that Pownall was "the most constitutional and national Governor... who ever represented the crown in this province."

Contents

Early Life and Travels in America

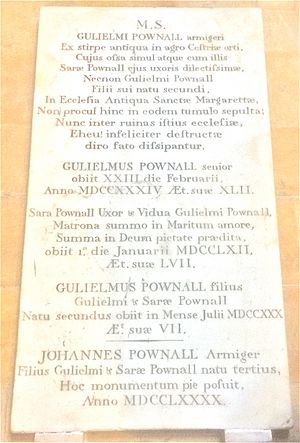

Thomas Pownall was the oldest son of William and Sarah Pownall. His father was a country gentleman and soldier. Sadly, his father's poor health and early death in 1735 caused the family to face hard times. Thomas was born in Lincoln, England, and went to Lincoln Grammar School. He then studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, graduating in 1743. His education taught him about classic thinkers and new scientific ideas. His first book, about how governments started, came from notes he took at Cambridge.

While Thomas was at Cambridge, his younger brother, John Pownall, got a job at the Board of Trade. This board managed British colonies. John quickly moved up in the government. The brothers helped each other advance their careers. John helped Thomas get a job in the colonial office. There, Thomas learned about opportunities in the colonies.

In 1753, Thomas went to America as a private secretary. He worked for Sir Danvers Osborne, the new governor of New York. But Governor Osborne died just a few days after arriving in New York. This left Pownall without a job or a sponsor. Pownall decided to stay in America. He wanted to learn about the American colonies.

For several months, he traveled widely. He went from Maryland to Massachusetts. He met important leaders and people in colonial society. He became friends with influential figures like Benjamin Franklin and Massachusetts Governor William Shirley.

Governor Osborne had been told to deal with growing problems with the six Iroquois nations. Their land was next to New York. Pownall had studied this issue. Because of his knowledge, he was invited to the 1754 Albany Congress. He attended as an observer. He saw how the colonies dealt with Native Americans. He noticed political fights over trade and unfair land deals. This led him to suggest new ideas for colonial management.

He proposed creating a royal superintendent for Native American affairs. He specifically suggested William Johnson. Johnson was New York's commissioner for Native American affairs and had a lot of influence with the Iroquois. Pownall also shared ideas for managing the colonies' expansion to the west.

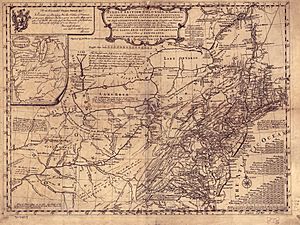

After the conference, Pownall returned to Philadelphia. He became closer friends with Franklin. They even started some business ventures together. Franklin had suggested uniting the colonies at the Albany conference. He might have helped Pownall with his writings, though it's not clear how much. In Philadelphia, Pownall also worked closely with mapmaker Lewis Evans. They both saw the need for accurate maps of North America's inner regions. These areas were being fought over with New France during the French and Indian War. The map Evans published in 1755 was dedicated to Pownall. This map made Pownall widely known. The British government followed Pownall's advice and appointed William Johnson as superintendent of Native American affairs in 1755.

Lieutenant Governor of New Jersey

Pownall had been paying his own way, hoping to get a government job. In May 1755, he was made Lieutenant Governor of New Jersey. He didn't have many duties, mostly waiting for the old governor, Jonathan Belcher, to die. He also attended military meetings about the ongoing war. However, Belcher lived longer than expected, dying in 1757, and Pownall grew restless.

The military meetings pulled him into a power struggle. This was between Johnson and Shirley. Shirley had become the military commander-in-chief after General Edward Braddock died in July 1755. Johnson used Pownall's worries about frontier safety to get him on his side. Pownall already disliked Shirley because of an earlier slight. Pownall's reports to New York Governor Sir Charles Hardy, along with other damaging claims from Johnson's supporters, led to Shirley being removed as commander-in-chief.

Pownall went back to England in early 1756. There, he confirmed Johnson's claims. As a reward, he was given a special job as "Secretary Extraordinary" to the new commander-in-chief, Lord Loudoun.

While Pownall was in England, Shirley's reputation suffered more. There were claims that he had let military information fall into enemy hands. The Board of Trade decided to recall him. Pownall was also offered the governorship of Pennsylvania. But he asked for too much power, so they took back the offer. Pownall used this to his advantage. He told everyone that he had turned down the offer because of the owners' "unreasonable, unenlightened attitude."

He returned to America with Loudoun in July 1756. But he went back to England again to represent Loudoun in hearings about Shirley's military leadership. Loudoun also told him about his military plans. In London, Pownall became very involved in telling members of the new government about North America. His good performance led to him being appointed governor of Massachusetts in March 1757. People admired his skill in colonial affairs. However, he was also criticized for being vain and having a bad temper. He was also blamed for Shirley's downfall.

Governor of Massachusetts Bay

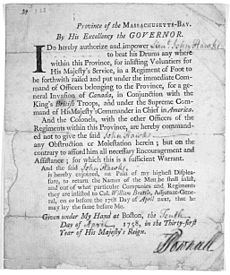

Pownall arrived in Boston in early August 1757. He was welcomed warmly and started his job on August 3. He immediately faced a war crisis. A French force was reportedly moving toward Fort William Henry in northern New York. The military commander there had urgently asked for militia. Pownall quickly organized the militia. But the call for soldiers came too late. Fort William Henry fell after a short siege. This was followed by terrible Native American attacks.

In September 1757, Pownall went to New Jersey for Governor Jonathan Belcher's funeral. He stopped in New York to meet with Loudoun. The commander-in-chief was angry that the Massachusetts General Court (the colonial assembly) had not fully met his demands. He blamed Pownall. Pownall argued against the military interfering in civilian matters. Loudoun used threats to get his way. Pownall believed the governor needed to lead the assembly, not force them. The meeting was very tense. Loudoun later wrote a harsh letter to London criticizing Pownall's ideas.

Loudoun faced opposition in the General Court. He demanded that British troops be housed with civilians in Boston. He threatened to send more troops into the province and take housing by force. Pownall asked the General Court to agree to some of Loudoun's demands. He eventually signed a bill allowing troops to be housed in inns and other public places. This bill was unpopular. Pownall was seen negatively in the local newspapers as supporting Loudoun's policies.

However, Pownall's letters to Loudoun show he understood the colonists' position. He wrote that the people of Massachusetts had the same "natural rights of English born subjects." He believed enjoying these rights would encourage them to fight "a cruel, invading enemy." He was also clear about the relationship between the royal governor and his assembly. He said a governor must "endeavour to lead those people for he cannot drive them." He was so committed to these ideas that he offered to resign. But Loudoun encouraged him to stay. Pownall later helped write parts of the 1765 Quartering Acts. This law was widely resisted in the colonies.

In January 1758, Pownall wrote to William Pitt. He explained the problems between the colonial government and the British military. He suggested that London pay more of the colonies' war expenses. When this idea was put into action, it led to many more militia joining the war. Massachusetts alone sent 7,000 men for the 1758 campaign. Pownall also got a bill passed in the General Court to reform the militia system. This bill gave local officials more power over the militia, reducing the governor's control.

Even with these changes, recruiting for the militia was hard. Recruiting parties were often bothered, leading to riots. But Pownall successfully recruited the province's full number of militia. His strong help in the war effort earned him praise from William Pitt and the Board of Trade. He also got approval from the new commander-in-chief, James Abercrombie.

Feeling successful, Pownall suggested to General Jeffery Amherst building a fort on Penobscot Bay. This would help fight against French movements in the area. This area had seen many frontier raids since 1755. This idea grew into a large expedition. It was approved by Amherst and the assembly. Pownall led the expedition and oversaw the building of Fort Pownall. He considered it a major success. Its success led to a small land rush in the area.

Although Pownall's start as governor was a bit difficult, his popularity grew. He worked hard to help the many fishermen in the province. He convinced military leaders to remove difficult paperwork. He also worked with local merchants. He invested in businesses run by Thomas and John Hancock. A group of Massachusetts merchants praised him when he left. Pownall was a bachelor and was known to be social. He regularly attended church services. He successfully handled difficult issues about recruiting and supplying the militia. He found compromises between military and provincial demands.

However, he had a strained relationship with his lieutenant governor, Thomas Hutchinson. The two men never trusted each other. Pownall often left Hutchinson out of his important meetings. Instead, he sent him on missions, like dealing with militia recruitment. One of Pownall's last actions before leaving was to approve James Otis Sr. as speaker of the assembly. Otis was a longtime opponent of Hutchinson.

In late 1759, Pownall wrote to William Pitt asking to return to England. He felt he "might be of some service" there. Some historians believe Pownall was frustrated. He was left out of major military actions in the later war years. He might also have wanted a more important job, like governor-general of conquered New France. Other historians think Pownall's dislike of Shirley's supporters, like Thomas Hutchinson, and local political fights contributed to his request. His difficult relationships with military commanders also played a part.

Whatever the reason, the Board of Trade changed some colonial positions after King George II died. Pownall was given the governorship of South Carolina. He was also allowed to take leave in England first. His departure from Boston was delayed by militia recruiting issues and a major fire in the city. He did not leave until June 1760.

The Administration of the Colonies

Although he was named governor of South Carolina, Pownall never actually went there. He described his time in Massachusetts as "arduous." In November 1760, he told the colonial office he would only accept another governorship if King George III directly ordered it. Pitt appointed him to a military office in the Electorate of Hanover. He served there until the Seven Years' War ended in 1763. This job did not help his career in colonial administration. It also led to claims of financial problems, but he was cleared of these.

When he returned to England, he prepared a book called The Administration of the Colonies. It was first published without his name in 1764. Pownall updated and republished the book several times between 1765 and 1777. The book was a detailed and complex study of North America. It included comments on the growing tensions in the Thirteen Colonies. Pownall wanted to show how the colonies could become a proper part of a larger empire.

Pownall's book showed he supported American liberty. He worried that Britain was losing control of its colonies. But he wrote that Americans deserved the same rights to representative government as people in England, Scotland, and Wales. At the same time, he said that the military protection from Britain meant colonists had to help pay for it. He also believed there needed to be a strong central government. This government would make policies that everyone in the British empire, including the American provinces, had to follow. Pownall eventually thought the only solution was to create an imperial parliament. This parliament would have representatives from both Britain and the colonies.

He was not the only British person to suggest an imperial parliament. But most Americans hated the idea. John Dickinson specifically criticized Pownall's plan in his famous Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1768).

Supporting the Colonies

Pownall kept in touch with his political friends in Massachusetts. He was often asked to speak to Parliament committees about colonial issues. He thought about returning to Massachusetts if he could find a job there. He also started buying land in Nova Scotia. This added to the colonial land he already owned in Maine from his time as governor.

In 1765, he married Harriet Fawkener. She was the widow of Everard Fawkener and the daughter of Lieutenant General Charles Churchill. This marriage connected him to the powerful Dukes of Marlborough. Pownall raised her four children as his own. Harriet was a kind and smart woman. She helped his political career by hosting social events and encouraging his intellectual interests. She may have encouraged him to run for Parliament in 1767. He won a seat representing Tregony.

He started writing to officials in Massachusetts again. He hoped to be appointed as an agent to represent the province's interests, but he was not successful. He often had visitors from the colonies. Benjamin Franklin, his old friend from Pennsylvania, was a frequent guest. Pownall watched with concern as tensions grew in the colonies. He saw how Parliament's mistakes made things worse instead of better.

He used his position in Parliament to highlight the colonists' objections to the Quartering Act of 1765 and other unpopular laws. In 1768, troops were sent to Boston after protests against the Townshend Acts turned violent. Pownall spoke in Parliament, warning that the ties between Britain and the colonies were breaking. He said this could lead to a permanent split.

Pownall opposed Lord North's partial repeal of the hated Townshend Acts in 1770. The tax on tea was kept as a symbol of Parliament's power. Pownall argued that keeping the tax would be a "millstone" around English necks, not a burden on Americans. He warned it would lead to civil war. He gave this speech on March 5, 1770, the same day as the Boston Massacre. He was discouraged that Parliament seemed to misunderstand the American colonial issues. He urged his colonial friends to keep pushing for constitutional rights and avoid violence.

Colonial American issues then became less important for a short time. In 1772, Pownall introduced a law to improve food production and distribution in Great Britain. It passed the House of Commons. But the House of Lords changed it, so the Commons rejected the changed bill. The bill passed the next year and was called "Governor Pownall's Bill." It received much praise, even from important people like Adam Smith. Pownall was also honored with membership in the Society of Antiquaries and the Royal Society.

Revolution and Later Life

After the Boston Tea Party in December 1773, Parliament passed a series of laws to punish Massachusetts. Pownall could not convince others to take a more peaceful approach. He was also involved in the Hutchinson Letters Affair. He may have given private letters from Thomas Hutchinson to Benjamin Franklin, though Franklin never said who his source was.

Pownall lost his seat in Parliament in 1774. Wanting to stay active, Pownall asked Lord North for help. North helped him get a seat in a special election, representing Minehead. This seemed like a shift towards supporting the King's party, which worried some of Pownall's colonial supporters. There is also some evidence that North might have caused Pownall to lose his first seat to gain his support.

Pownall supported North's attempts to make peace in the debates before the War of Independence. However, once fighting began in April 1775, his peaceful ideas were ignored. Those who supported the war opposed him. Those who wanted to limit the King's power saw his ideas as trying to weaken their position. Pownall continued to support North until 1777. Then, he openly declared his support for the peace party. When France entered the war on the American side, he firmly returned to supporting the war.

His support was complex. He still argued for some kind of agreement with the Americans. But he also remained very patriotic towards the French. He was not alone among British politicians in struggling to balance these views. He refused to run for re-election in 1780.

During the war, he published several updated versions of The Administration of the Colonies. He expanded the book to reflect the changing situation. He also worked to update the Evans map. He asked for new information and maps from his colonial contacts. He withdrew somewhat after his wife died in 1777, but he continued to appear in Parliament.

Later Life and Legacy

In July 1780, Pownall anonymously published an essay called A Memorial Most Humbly Addressed to the Sovereigns of Europe. This widely published document brought Pownall attention across Europe. People figured out he was the author because he used long parts from Administration of the Colonies. The essay gave advice to European leaders on how to deal with a newly independent United States. He pointed out that America's independence and fast population growth would greatly change world trade. He suggested that European leaders meet to create worldwide rules for free trade.

Pownall continued to be interested in the United States after the war. However, he never returned there. He tried to get a formal commission in the Massachusetts militia. This was mostly a formality so he could show it during his travels in Europe. He kept writing essays, both new ones and revisions of older ones. He also published an updated version of his 1755 map.

In his later years, Pownall met Francisco de Miranda. Miranda was a Venezuelan general who wanted Latin American countries to be independent from Spain. According to historian William Spence Robertson, many of Miranda's later arguments came from Pownall's influence. Pownall also directly helped Miranda. He used his connections in the British government to help Miranda's independence goals. Pownall's last major work was a book arguing for free trade. It also clearly called for British support of Latin American independence. This would open those markets to British and American trade. Pownall died in Bath on February 25, 1805. He was buried in the church at Walcot.

Antiquarian Interests

Thomas Pownall is known as a colonial governor and politician. But he was also important in the study of ancient things and archaeology in the late 1700s. Bryony Orme, who studied Pownall, said he is "perhaps one of the most neglected of our early antiquaries, and undeservedly so." He got these interests from his father, Captain William Pownall. His father had written to William Stukeley about ancient discoveries around Lincoln. Thomas Pownall's brother John also wrote about archaeology. Pownall showed his interest in archaeology before he left for America. In 1752, he recorded evidence of a Roman villa at Glentworth in Lincolnshire.

After he returned from America, he became a member of the Society of Antiquaries of London in 1770. He wrote many articles for the early issues of the journal Archaeologia. Some of his writings described discoveries around Lincoln. More importantly, he wrote about Newgrange in Ireland in 1773. He also wrote about Braich-y-Dinas at Penmaenmawr, on the North Wales coast. He later described Roman remains in France when he lived there. When he moved to Bath, he again provided descriptions of Roman discoveries.

Family and Places Named After Him

Pownall married twice. His first wife was Harriet Churchill. She was the widow of Sir Everard Fawkener and the daughter of Lieutenant General Charles Churchill. In 1784, Pownall married Hannah (Kennet) Astell. Through this marriage, he gained significant land and the lifestyle of a wealthy landowner.

The towns of Pownal, Maine and Pownal, Vermont are named after Thomas Pownall. Dresden, Maine was once called Pownalborough in his honor. This recognition lives on in the Pownalborough Courthouse, a historic building built there in 1761. The remains of Fort Pownall, named for him, can still be seen in Maine's Fort Point State Park.

Who Was Junius?

Between 1769 and 1772, a series of letters appeared in London's Public Advertiser newspaper. They were written by someone using the secret name Junius. Many of these letters accused British government officials of corruption and misusing their power. These were topics Pownall also spoke and wrote about.

The true identity of Junius has been a mystery and a topic of debate for a long time. In 1854, Frederick Griffin wrote Junius Uncovered. He argued that Pownall was Junius. This idea was brought up again by Pownall's descendant, Charles A. W. Pownall, in his 1908 book about Pownall. However, modern experts disagree. They currently believe Philip Francis was the writer of the letters, based on various clues.

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |