Hutchinson Letters affair facts for kids

The Hutchinson Letters affair was an important event that made things much worse between the American colonists and the British government. This happened right before the American Revolution.

In June 1773, some letters were published in a Boston newspaper. These letters had been written a few years earlier by Thomas Hutchinson and Andrew Oliver. At the time of publication, Hutchinson was the governor of Massachusetts, and Oliver was the lieutenant governor. People in Massachusetts who wanted more freedom claimed the letters showed that Hutchinson and Oliver wanted to take away the colonists' rights. This caused a lot of anger.

The incident made people in Massachusetts even more upset. This anger grew, especially when the 1773 Tea Act was put into action. It all led to the famous Boston Tea Party in December 1773. The way the British government reacted to the letters also changed Benjamin Franklin. He was a key person in this affair and became a strong supporter of American independence, known as a Patriot.

Contents

Why It Happened: The Background

In the 1760s, Great Britain and its North American colonies started having problems. The British Parliament passed several laws to raise money and show its power. These laws included the 1765 Stamp Act and the 1767 Townshend Acts. Many colonists felt these laws were unfair because they had no say in Parliament. This idea was called "no taxation without representation."

These laws caused big protests in the Thirteen Colonies. The Province of Massachusetts Bay saw a lot of unrest and direct action against British officials. British soldiers were sent to Boston in 1768, which made tensions even higher. This eventually led to the Boston Massacre in 1770, where soldiers shot and killed several colonists.

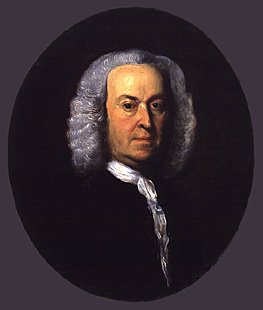

After the Townshend Acts, Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson and his brother-in-law, Andrew Oliver, wrote letters. They sent these letters to Thomas Whately, who worked for the British Prime Minister. The letters talked about the acts, the protests, and ideas on how to handle the situation. Whately died in 1772, and his papers, including the letters, went to his brother.

Hutchinson became governor of Massachusetts in 1770. For the next two years, he had many arguments with the local assembly and the governor's council. These groups were controlled by leaders who did not like British rule. Their debates were about the governor's power and Parliament's role in governing the colonies. This made the divisions in Massachusetts much deeper.

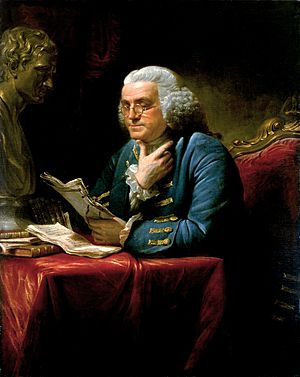

The arguments in Massachusetts reached England. Lord Dartmouth, a British official, told Benjamin Franklin to make the Massachusetts assembly take back some statements. Franklin was working in London as a representative for Massachusetts. He got a group of about twenty letters that had been sent to Whately.

After reading the letters, Franklin believed that Hutchinson and Oliver had given wrong information about the colonies. He thought they had misled Parliament. Franklin felt that if colonists knew what was in the letters, their anger would shift. Instead of being angry at Parliament, they would be angry at the people who wrote the misleading letters.

Franklin sent the letters to Thomas Cushing, who was the speaker of the Massachusetts assembly, in December 1772. He told Cushing very clearly not to publish or share them widely. Franklin said they should only be seen by a few people.

The letters arrived in Massachusetts in March 1773. They ended up with Samuel Adams, who worked for the assembly. Following Franklin's rules, only a few chosen people, like the Massachusetts Committee of Correspondence, saw the letters. What they read worried them. Cushing wrote to Franklin, asking if they could share the letters more freely. Franklin replied in early June, repeating that the letters should not be copied or published. However, he said they could be shown to anyone.

How They Were Published

Samuel Adams, who had long opposed Hutchinson, followed Franklin's rules carefully. But he still managed to start a campaign against Hutchinson without immediately showing the letters. He told the assembly that the letters existed. The assembly then formed a committee to study them.

Hints about the letters' content were leaked to newspapers and political talks. This made Hutchinson very uncomfortable. The assembly eventually decided that Hutchinson, in his letters, wanted to "overthrow the Constitution of this Government." They believed he wanted to bring "arbitrary Power into the Province." So, they asked for Hutchinson and Oliver to be removed from their jobs.

Hutchinson complained that Adams and his opponents were twisting his words. He said he had not written anything about Parliament's power that he had not said publicly before. The letters were finally published in the Boston Gazette in mid-June 1773. This caused a huge political uproar in Massachusetts and raised many questions in England.

What the Letters Said

Most of the letters were written in 1768 and 1769. They were mainly from Hutchinson and Oliver. The published collection also included some letters from Charles Paxton, a customs official, and Nathaniel Rogers, Hutchinson's nephew.

Oliver's letters suggested big changes to the Massachusetts government. He wanted to make the governor's power much stronger. Hutchinson's letters were more like his thoughts on the difficult situation in the colony. Historians say that much of what Hutchinson wrote was similar to things he had already said in public.

One of Hutchinson's thoughts was that colonists could not have all the same rights as people in England. He felt it might be necessary to "abridge what are called English liberties." This meant taking away some freedoms. Unlike Oliver, Hutchinson did not suggest specific ways to change the colonial government. He wrote in one letter that was not published, "I can think of nothing but what will produce as great an evil as that which it may remove."

Oliver's letters, however, made clear suggestions. He proposed that the governor's council should no longer be elected by the assembly. Instead, its members should be chosen by the British King.

What Happened Next

In England, everyone wondered who had leaked the letters. William Whately accused John Temple of taking them. Temple denied it and challenged Whately to a duel. Whately was hurt in the fight in December 1773. Neither was happy, and a second duel was planned.

To stop another fight, Franklin published a letter on Christmas Day. He admitted that he was the one who got and sent the letters. He said he did it to prevent "further mischief." Franklin explained that he felt it was right because the letters were written by public officials to influence government policy.

When Hutchinson's opponents in Massachusetts read the letters, they focused on key phrases. The "abridgement" phrase was one of them. They argued that Hutchinson was secretly trying to get the London government to take away their rights. Combined with Oliver's clear suggestions for changes, this seemed like proof. It looked like the colonial leaders were working against the people's interests.

People in Boston were furious about the published letters. They burned figures of Hutchinson and Oliver on Boston Common. The letters were printed again in many other colonies. Protests happened as far away as Philadelphia.

The Massachusetts assembly and governor's council asked the British government to remove Hutchinson from his job. There was a hearing in England about Hutchinson's future. The Boston Tea Party was also discussed there. Franklin stood silently while a British lawyer, Alexander Wedderburn, strongly criticized him. Franklin was accused of stealing and being dishonest. He was called the main person in England helping Boston's radical Committee of Correspondence.

The British government then removed Franklin from his job as colonial Postmaster General. They also said the request to remove Hutchinson was "groundless" and "vexatious." Parliament then passed the "Coercive Acts." These were a group of laws meant to punish Massachusetts for the tea party.

Hutchinson was called back to England. The Massachusetts governorship was given to Thomas Gage, the commander of British forces in North America. Hutchinson left Massachusetts in May 1774 and never came back. Andrew Oliver had a stroke and died in March 1774.

Gage's actions to enforce the Coercive Acts made tensions even higher. This led to the start of the American Revolutionary War in April 1775. Before his appearance in England, Franklin had been somewhat neutral about the colonial radicals. But he returned to America in early 1775, fully committed to independence. He became a very important leader in the American Revolution.

Who Leaked the Letters to Franklin?

Many people have been suggested as the person who gave the letters to Franklin. John Temple, despite his political differences with Hutchinson, seemed to convince Hutchinson in 1774 that he was not involved. However, Temple claimed to know who was involved but would not say, because it would "prove the ruin of the guilty party."

Several historians believe that Thomas Pownall was likely the source of the letters. Pownall was governor of Massachusetts before Hutchinson. He had similar ideas to Franklin about colonial matters. He also had access to important colonial government offices through his brother, John, who was a colonial under-secretary.

Other people have also been suggested, but their connection to Franklin or the situation seems weak. Historians say that we might never know for sure who gave Franklin the letters unless new documents are found.

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |