Mercy Otis Warren facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mercy Otis Warren

|

|

|---|---|

Warren c. 1763

|

|

| Born | Mercy Otis September 28, 1728 Barnstable, Massachusetts Bay, British America |

| Died | October 19, 1814 (aged 86) Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | Burial Hill, Plymouth, U.S. 41°57′22″N 70°39′58″W / 41.956°N 70.666°W |

| Pen name | A Columbian Patriot |

| Occupation | Poet and political writer |

| Language | English |

| Education | Writer (History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5 |

Mercy Otis Warren (September 25, 1728 – October 19, 1814) was an American writer and activist during the American Revolution. She wrote poems, plays, and pamphlets that encouraged colonists to stand up against British rule. She was married to James Warren, who was also very involved in the fight for independence.

Before the Revolution, Mercy Warren wrote about how the British government was taking away the colonists' rights. In 1788, during the debate about the U.S. Constitution, she wrote a pamphlet called Observations on the new Constitution. She used a fake name, "A Columbian Patriot," to share her ideas. She believed the Constitution needed a Bill of Rights to protect people's freedoms. For a long time, people thought someone else wrote this pamphlet. But later, her descendant, Charles Warren, found proof that Mercy Warren was the true author. In 1790, she published a book of her poems and plays under her real name. This was very unusual for a woman at that time. In 1805, she wrote one of the first histories of the American Revolution, a three-volume book.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Mercy Otis Warren was born on September 25, 1728, in Barnstable, Massachusetts. She was the third of thirteen children and the first daughter of James and Mary Otis. Her father was a farmer and a lawyer. He was also a judge and a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives. He strongly disagreed with British rule and the colonial governor, Thomas Hutchinson.

Mercy grew up in a family that believed in revolutionary ideas. Even though girls usually didn't get formal schooling back then, Mercy studied with her brothers' tutor, Reverend Jonathan Russell. She learned much more than most girls of her time. Her father supported her desire to learn, which was very rare in the 1700s. Her brother James went to Harvard College and became a famous patriot and lawyer. He encouraged Mercy's writing and treated her as an equal.

Family Life and Patriot Connections

Mercy married James Warren on November 14, 1754. They lived in Plymouth, Massachusetts. James worked as a farmer and merchant before becoming a sheriff, like his father. They wrote many letters to each other, showing their deep respect and love. James would call her "a Saint," and Mercy would write about how important it was for people to have the same spirit as him to stand up to Britain. They had five sons: James, Winslow, Charles, Henry, and George.

Her husband, James, had an important political career. He was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1766. He became the speaker of the House and president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. He also managed money for George Washington's army during the American Revolutionary War.

Their home in Plymouth was a popular meeting spot for patriots and revolutionaries, including the Sons of Liberty. Mercy became more and more involved in politics. She hosted protest meetings at her house. These meetings helped start the Committees of correspondence, which connected different colonies. Mercy believed these committees were very important for uniting the colonies and gaining independence. She wrote that "Every domestic enjoyment depends on the unimpaired possession of civil and religious liberty." Her husband, James, encouraged her writing and called her his "scribbler." She became his main helper and trusted advisor.

Writing for the Revolution

Mercy Warren had many important friends she wrote to regularly. These included Abigail Adams, John Adams, Martha Washington, and Hannah Winthrop. She wrote to historian Catharine Macaulay, saying that America was ready to fight but still didn't want to go against Britain, the country it came from. Yet, she said, Britain was acting like an "unnatural parent."

She became a trusted advisor to many political leaders, such as George Washington, Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Patrick Henry, and Thomas Jefferson. John Adams was especially important to her writing career before the Revolution. He even suggested she write a history of the Revolution while the war was still happening. For this project, she used her own memories and asked leaders for copies of debates and letters.

Before and during the Revolution, the Warren home was a place for patriot leaders to meet and discuss ideas. This allowed Mercy to meet many important figures and their wives. Her husband, James, was part of the Massachusetts Committee of Correspondence and managed the Continental Army's money. Mercy often traveled with him to act as his secretary. Her important position allowed her, as a woman, to be part of the revolutionary discussions. She formed strong opinions about many leaders. She described George Washington as "one of the most amiable and accomplished gentlemen." Years later, in 1790, Washington approved her history book. Thomas Jefferson also helped her get people to buy her book.

However, her book also caused problems with John Adams. After the Revolution, Mercy supported Jeffersonian Republicanism, which was different from Adams's views. She wrote harshly about Adams in her history book, ending their long friendship. She also disagreed with John Hancock, who had once been unsure about independence.

Mercy Warren wrote several plays. Her play The Adulateur (1772) made fun of Governor Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts. It even predicted the Revolutionary War. The play featured a character named "Rapatio" who represented Hutchinson. Mercy was a Whig, and Hutchinson was a Tory, so she disagreed with his ideas. The hero of the play, "Brutus," represented her brother, James Otis. In the play, the Whigs were brave, and the Tories were selfish. The play had a happy ending for the Whigs. After it was published, people started calling Hutchinson "Rapatio."

In 1773, she wrote The Defeat, which also featured a character based on Hutchinson. This play helped remove Governor Hutchinson from his position. Mercy wondered if her writing was too strong for a woman, but Abigail Adams encouraged her, saying God had given her powers "for the good of the World." In 1775, Mercy published The Group, which imagined what would happen if the British king took away Massachusetts's rights. Other plays, The Blockheads (1776) and The Motley Assembly (1779), are also thought to be hers. In 1788, she wrote Observations on the New Constitution, opposing its approval as an Anti-Federalist.

Mercy Warren was a powerful voice for the Patriots. Her writings inspired many people to join the cause. Important men like George Washington and Alexander Hamilton praised her work. Hamilton even said that women writers in the U.S. were better than men in drama.

Later Writings and Legacy

Mercy Warren's works were published without her name until 1790. That year, she published Poems, Dramatic and Miscellaneous, which was the first book with her name on it. It included eighteen political poems and two plays. The plays, "The Sack of Rome" and "The Ladies of Castille," explored ideas of freedom and the good values needed for the new country to succeed.

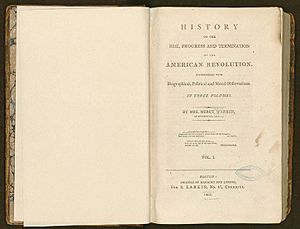

In 1805, she finished her most famous work, a three-volume book called History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution. President Thomas Jefferson bought copies for himself and his cabinet. He said her book would teach people more about the last thirty years than any other history. Because she knew Presidents Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, her book is considered one of the most important histories of the Revolution written by someone who lived through it. However, her strong opinions about John Adams in the book led to a bitter argument and ended their friendship until 1812. John Adams was upset and wrote to a friend, "History is not the province of the ladies."

Death and Remembrance

Mercy Warren passed away on October 19, 1814, at 86 years old. She is buried next to her husband at Burial Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Even though she first doubted if women should write about politics, her friends convinced her to use her talents for the patriot cause. She became a self-taught historian with a writing style that readers of her time enjoyed. Her plays and histories showed her strong opinions against Governor Hutchinson and later the Federalists. Today, historians read her work to understand the feelings and ideas of intellectuals during the Revolutionary era. Some people debate if she was a feminist, as she encouraged women writers but also stressed traditional household duties.

Mercy Warren was able to connect with both men and women in the colonies. She bravely wrote about powerful leaders while also raising a family. She told her son George that politics often brings "ruin to the adventurer." Yet, people continued to ask for her thoughts on political issues throughout her life.

The SS Mercy Warren, a ship built during World War II in 1943, was named in her honor. In 2002, she was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. She is also remembered on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail. Her great-great-grandson, Charles Warren, became a well-known lawyer and historian.

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |