Massachusetts Convention of Towns facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Massachusetts Convention of Towns |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| History | |

| Founded | 09/22/1768 |

| Disbanded | 09/28/1768 |

| Preceded by | Massachusetts General Assembly (disbanded) |

| Succeeded by | Massachusetts Provincial Congress |

| Leadership | |

|

Chairman

|

Thomas Cushing

|

| Meeting place | |

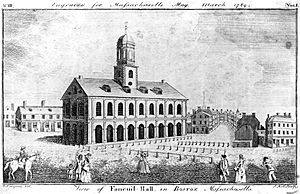

| Faneuil Hall | |

The Massachusetts Convention of Towns was a special meeting held in Boston from September 22 to 29, 1768. It was an unofficial gathering, not approved by the British government. This meeting happened because people in Massachusetts heard that British soldiers were coming. These troops were sent to stop protests against British rules.

Delegates, or representatives, from 96 towns in Massachusetts came together. They met in Faneuil Hall to talk about what they should do. Some leaders, like James Otis Jr., Samuel Adams, and John Hancock, wanted to fight back. They thought about organizing armed resistance. Others, like the convention's chairman Thomas Cushing, wanted to send a written complaint to the British government. The group decided to send a polite complaint. They passed a few calm resolutions before the meeting ended.

Contents

History of the Convention

Why the Convention Happened

In early 1768, the Massachusetts House of Representatives wrote a letter. This letter spoke out against the Townshend Acts, which were new taxes from Britain. They sent this letter to other colonies. The British government, especially Lord Hillsborough, told the House to take back the letter. When they refused, Governor Francis Bernard closed down the Massachusetts assembly. This made many colonists angry because they had no official way to share their complaints.

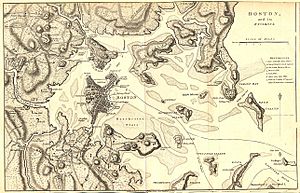

On June 10, customs officers took John Hancock's ship, the Liberty. This caused big riots in Boston. The officers had to hide at Castle William, a fort on an island. Governor Bernard asked the British government to send soldiers to Boston. He wanted them to control the "trained mob." On September 3, the governor let it be known that British troops would arrive soon.

Rumors spread that thousands of redcoats (British soldiers) were coming. People feared these soldiers would scare them and force them to obey unfair laws. They worried about a standing army living among civilians. This, they thought, would make them "the very borders of slavery." Samuel Adams said they would fight before the King could force officers on them. The Sons of Liberty, a group of patriots, started secret meetings. They planned how to resist. They even thought about taking over Castle William. This would let them stop British ships from entering Boston Harbor.

Boston's Town Meeting

On September 12 and 13, Boston held a town meeting at Faneuil Hall. Samuel Adams, James Otis Jr., and Joseph Warren led this meeting. Otis was the leader for the discussion. Many Sons of Liberty members were there. First, they asked Governor Bernard to call the assembly back together. The governor said no, claiming he needed permission from his bosses. After this, the discussion became more serious.

To avoid being charged with treason, the patriots pretended. They said the colonies were about to be attacked by the French. They told all Bostonians to get their own weapons, as local law required. They wanted "a well fixed Firelock Musket Accoutrement and Ammunition." These weapons would be used against "the enemy." The town's weapons were put on display. Some wanted to give them out right away, but this was seen as too extreme. Otis said, "there are the Arms, when an attempt is made against your Liberties they will be delivered."

The Bostonians passed several resolutions. They said that having a standing army among them without their permission was against the law. They promised to defend the King but also their own rights. They would do this "at the utmost peril of their lives and fortunes." They also decided to hold a meeting for the whole province. This meeting would start on September 22. Otis, Adams, Hancock, and Thomas Cushing were chosen to organize it. The town leaders then sent letters to other towns. They explained their worries and invited them to send delegates to the convention. Thomas Hutchinson, who was lieutenant governor, later wrote that this meeting was a big step towards a revolution.

Around the time of the town meeting, the Sons of Liberty built a simple beacon. It was a barrel of turpentine on a pole on Beacon Hill. The plan was to light it when British warships appeared. This would signal people from inland Massachusetts to march to Boston. They would then "destroy every Soldier that dares put his Foot on Shore." The town leaders were told to take the beacon down. When they refused, the sheriff removed it. On September 19, Governor Bernard officially announced that British soldiers from Halifax and Ireland were coming.

The Convention Gathers

Delegates from 96 Massachusetts towns and 8 districts arrived in Boston on September 22, 1768. The convention lasted for a week. More than half of the delegates had also been in the Massachusetts House earlier that year. For some reason, James Otis missed the first three days. His absence likely made the more radical members feel less confident.

The convention was much calmer than the Boston town meeting. Thomas Cushing said the goal was to bring together "prudent people." He hoped they would "check the violent designs of Others." Samuel Adams tried to push for more radical actions, but the moderate members stayed firm. Many delegates had been told by their towns to be careful. They were not to do anything that seemed rebellious. Some towns, like Middleborough, clearly opposed the arrival of troops. Braintree and Lexington said standing armies were against the law. But most delegates from the countryside were more cautious than those from Boston. The convention's first action was to tell the governor they had no official power.

The delegates politely asked the governor to call the assembly. Bernard ordered the convention to break up, saying it was illegal. This scared some of the more timid members. But the convention continued. The delegates sent a very respectful petition to the King. They expressed their loyalty and their "love of peace and good order." Even so, historian Richard D. Brown says the convention itself showed a revolutionary spirit. Most politically active towns were willing to defy the governor by attending this unofficial meeting. John C. Miller called the convention an early version of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress.

What Happened Next

Before the convention ended, a rumor spread in London. People thought Massachusetts was openly rebelling and had called its militia to fight the British. This news was so worrying that stock prices dropped in London.

When the British troops sailed into Boston Harbor in October, they came carefully. They were ready for a fight. Their guns pointed at the town. The ships lined up as if preparing for a siege. According to Thomas Cushing, the troops landed "in Battle Array." They expected strong resistance because of the rumors.

By this time, the radical Bostonians had agreed to follow the moderate majority. They knew they could not defeat the British alone. The soldiers marched through Boston without opposition. They took control of Faneuil Hall. The patriots tried to stop them from finding places to live, but even that failed. The soldiers were housed in the town.

After all their strong talk, the Boston patriots were made fun of by other colonies. They had failed to fight the troops. New Yorkers joked about their "ridiculous Puff and Bombast." General Gage wrote that the people of Boston were "very bold in Council, but never remarkable for their Feats in Action." English politicians thought the patriots made empty threats and should not be taken seriously.

The soldiers' presence increased tensions in Boston. An anonymous journal, the Journal of Occurrences, recorded what happened during the occupation. This journal helped unite the colonies. Boston received much-needed support from other colonies when the Boston Port Bill was passed in 1774.

Towns That Participated

The following towns sent delegates to the convention. A slash (/) means one delegate represented two or more towns. All delegates were men, as was common then. They were almost certainly all white. Governor Bernard later wrote that there were "very few Gentlemen there," meaning not many wealthy landowners.

The convention records say 96 towns were represented. If that number is correct, this list is not complete. Please remember that some town and county names and borders have changed since 1768. Some towns are now part of Maine.