Great Fire of New York (1776) facts for kids

| Part of the New York and New Jersey campaign of the American Revolutionary War | |

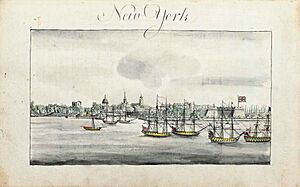

A contemporaneous artist's interpretation of the fire, published in 1776

|

|

| Date | September 21, 1776 |

|---|---|

| Location | New York City |

| Outcome | 400 – 1,000 structures destroyed |

The Great Fire of New York was a huge fire that burned for a long time. It started on the night of September 20, 1776, and continued into the next morning. The fire happened on the west side of what was then New York City. This area is at the southern tip of Manhattan island. The fire broke out soon after British forces took control of the city during the American Revolutionary War.

The fire destroyed about 10 to 25 percent of the city's buildings. Some areas not touched by the fire were robbed. Many people thought someone had started the fire on purpose. British leaders blamed American revolutionaries. Many residents also believed one side or the other was responsible. The fire had lasting effects on the British control of the city, which lasted until 1783.

Contents

The City Before the Fire

The American Revolutionary War began in April 1775. New York City was already an important business center. However, it was not yet a huge city. It only covered the lower part of Manhattan island. About 25,000 people lived there. Before the war, the Province of New York was divided. Some people were Patriots, who wanted independence. Others were Loyalists, who supported the British King. After the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Patriots took control of the city. They began arresting Loyalists or making them leave.

In the summer of 1776, British General William Howe wanted to take control of New York City. Its harbor was very important for the war. He first took Staten Island in July. Then, he successfully attacked Long Island in late August. His brother, Admiral Lord Richard Howe, helped with naval forces. American General George Washington knew New York City would be captured. He moved most of his army about 10 miles (16 km) north to Harlem Heights.

Some people, like General Nathanael Greene, suggested burning the city. This would prevent the British from using it. Washington asked the Second Continental Congress about this idea. They said no, stating the city "should in no event be damaged."

On September 15, 1776, British forces landed on Manhattan. The next morning, some British troops marched towards Harlem. There, the two armies fought again. Other British troops marched into the city.

Many people had already left the city before the British arrived. When American troops came in February, some Loyalists left. The capture of Long Island made even more people leave. The American army used many empty buildings. When the British arrived, they also took over buildings that belonged to Patriots. This meant there were not enough homes for everyone, especially with so many soldiers.

The Fire Spreads

An eyewitness, John Joseph Henry, was an American prisoner on a British ship. He said the fire started at the Fighting Cocks Tavern. This tavern was near Whitehall Slip. However, where the fire truly began is still debated. Some believe it started in many places, or at Trinity Church.

The weather was dry, and strong winds helped the fire spread quickly. The flames moved fast through the city's tightly packed wooden homes and businesses. The narrow streets also helped the fire spread. People rushed into the streets, carrying what they could. They found safety on the grassy town commons, which is now City Hall Park.

The fire crossed Broadway near Beaver Street. Then, it burned most of the city between Broadway and the Hudson River. The fire burned all night and into the next day. It finally stopped when the wind changed direction. Some citizens and British marines also helped put it out. The fire may also have stopped at the less developed land of King's College. This college was at the northern edge of the burned area.

Estimates say that between 400 and 1,000 buildings were destroyed. This was about 10 to 25 percent of the 4,000 buildings in the city at that time. Trinity Church was destroyed, but St. Paul's Chapel survived. Rebuilding Trinity Church became a sign of hope for New Yorkers.

Who Started the Fire?

General Howe told London that the fire was set on purpose. He wrote that "a most bad attempt was made by a number of wretches to burn the town." Royal Governor William Tryon thought Washington was responsible. He wrote that "many circumstances lead to conjecture that Mr. Washington was privy to this villainous act." He also said "some officers of his army were found concealed in the city." Many Americans also thought Patriots had started the fire. John Joseph Henry wrote that marines said they caught men "in the act of firing the houses."

Some Americans accused the British of starting the fire so they could steal things. A Hessian soldier wrote that some who fought the fire also "paid themselves well by plundering other houses near by that were not on fire." While stealing likely happened during the fire, there is no proof the British planned it.

Washington wrote to John Hancock on September 22. He said he did not know what caused the fire. In a letter to his cousin Lund, Washington wrote, "Providence—or some good honest fellow, has done more for us than we were disposed to do for ourselves." This suggests he was happy about the fire, even if he didn't cause it.

Historian Barnet Schecter says no claim of arson has ever been proven. The strongest clue for arson was that the fire seemed to start in many places. However, people at the time said that burning pieces of wooden roofs spread the fire. One person wrote that "the flames were communicated to several houses" by debris "carried by the wind to some distance."

The British questioned over 200 suspects. But no one was ever charged with starting the fire. Interestingly, Nathan Hale, an American captain spying for Washington, was arrested in Queens the day the fire started. This made some people link him to the fire, but there was no real proof.

Life Under British Control

Major General James Robertson took over empty homes of known Patriots. He gave them to British officers. Churches, except for the official Church of England churches, were turned into prisons, hospitals, or barracks. Some soldiers stayed with civilian families. Before the fire, the British already worried about housing soldiers. The fire made this problem much worse.

In the weeks after the fire, many Loyalist refugees came to the city. This made the overcrowding even worse. Many Loyalists from Patriot-controlled areas lived in messy tent cities on the burned ruins. This caused problems between Loyalists and British leaders. Loyalists often expected help and protection, but did not always get it.

The fire convinced the British to put the city under martial law. This meant the military, not civilian leaders, would rule the city. Martial law was also used because New York was already occupied and divided. Crime and poor sanitation were ongoing problems during the British control. The British did not leave the city until November 25, 1783.

See also

In Spanish: Gran incendio de Nueva York de 1776 para niños

In Spanish: Gran incendio de Nueva York de 1776 para niños