History of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom facts for kids

The history of the United Kingdom's foreign relations looks at how England, and later Great Britain and the United Kingdom, dealt with other countries from around 1500 to 2000. For what's happening since 2000, you can check out foreign relations of the United Kingdom.

From the mid-1700s to the early 1900s, Britain was very proud of its strong economy. It had powerful industries, banks, shipping, and trade that led the world. A policy of free trade (from the 1840s to the 1920s) helped the economy grow. The first British Empire lost many of its lands when the thirteen American colonies broke away in a war where Britain had no big allies.

A new empire, the Second British Empire, was then built in Asia and Africa. It was strongest in the 1920s. Britain's foreign policy made sure this empire was safe. In 1931, the Statute of Westminster gave the self-governing parts of the Empire, called Dominions, their independence. Starting with India in 1947, many colonies gained independence by the 1960s, with only a few left by the 1970s.

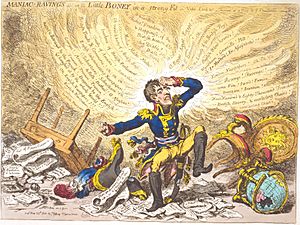

Peace was common, but there were big conflicts, especially against France from the 1790s to 1815. After this, Britain did not fight another war in Europe until World War I, which cost a lot. After defeating the First French Empire and Napoleon (1793–1815), Britain focused on keeping a balance of power in Europe. This meant making sure no single country became too strong. This was a main reason for Britain's wars against Napoleon and, for some, Germany in World War I. Until 1815, the main enemy was France, which had a larger population and a powerful army. The Royal Navy was a huge advantage for Britain. The British usually won their wars, with the American War of Independence (1775–1784) being a rare exception.

A favorite way to deal with other countries was to pay for the armies of allies in Europe, like the Kingdom of Prussia. This turned London's money power into military strength. Britain relied heavily on its Royal Navy for safety. It aimed to keep its navy the strongest in the world, with bases everywhere. The Royal Navy's control of the seas was key to building the British Empire. For most of the 1800s and early 1900s, the British Navy was larger than the next two biggest navies combined. The British ruled the oceans. The Royal Navy was so strong that it didn't need to fight much from 1812 to 1914. While other big countries fought their neighbors, the British Army only had one somewhat small war (the Crimean War against the Russian Empire in 1854–56). The army mostly guarded places and dealt with small uprisings and conflicts in Asia and Africa.

For a quick look at the wars, see list of wars involving the United Kingdom.

Contents

- Early English Foreign Policy (Before 1700)

- Wars with France (1702–1815)

- Defeating Napoleon (1803–1814)

- The "British Peace" (1814–1914)

- Early 1900s (1900–1914)

- First World War (1914-1918)

- Between the World Wars (1919–1939)

- Second World War (1939-1945)

- Since 1945

- See also

- Timeline

Early English Foreign Policy (Before 1700)

In 1500, the Kingdom of England had a small population (3.8 million) compared to bigger rivals like France (15 million), Spain (6.5 million), and the Holy Roman Empire (17 million). It was three times bigger than its sea rival, the Netherlands, and eight times bigger than Scotland. England had a small budget and didn't try to conquer much in Europe. The English Channel also protected it from invasions. Because of this, foreign affairs were less urgent for the English government before 1688. Important people didn't pay much attention to Europe before the 1660s, and there wasn't much desire to join the Thirty Years War (1618–48). Historian Lawrence Stone said England was "no more than a small player in the European power game." The growing Royal Navy was admired, but London used it to support its expanding empire overseas.

Tudor Kings and Queens (1485-1603)

King Henry VII (ruled 1485–1509) started the Tudor family that ruled until 1603. He focused on bringing peace to England, especially against threats from the recently defeated House of York. Foreign affairs, except with Scotland, were not a top concern. Scotland was an independent country, and peace was agreed in 1497. Much of his diplomacy involved arranging marriages with royal families in Europe. He married his oldest daughter Margaret Tudor to King James IV of Scotland in 1503. This marriage didn't bring peace right away, but it did in the long run: in 1603, James VI and I, the grandson from this marriage, united the two kingdoms under his rule. Henry tried to marry his daughter Mary to the future Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, but that didn't happen. Henry VIII eventually married her to King Louis XII of France as part of a peace treaty in 1514. Louis died after three months, and Henry demanded and got most of her dowry back. Henry VII's other main diplomatic success was an alliance with Spain, sealed by the marriage in 1501 of his heir, Arthur, Prince of Wales, to Catherine of Aragon, the Spanish king's oldest daughter. When his queen died in 1503, Henry VII looked for a diplomatic marriage for himself with a large dowry, but he couldn't find a match.

Arthur died in 1502, and Henry VII's second son married Catherine in 1509, right after he became King Henry VIII.

King Henry VIII's Rule (1509-1547)

King Henry VIII (ruled 1509–1547) was one of England's most famous and colorful monarchs. He greatly expanded the English Navy to protect the growing merchant fleet. He also hired privateers (private ships allowed to attack enemy ships) from merchant fleets to act as extra warships. Some of his foreign and religious policies were about ending his marriage to Catherine of Aragon in 1533, even though Pope Clement VII was against it. His solution was to remove the Church of England from the Pope's control, starting the English Reformation.

In 1510, France, allied with the Holy Roman Empire in the League of Cambrai, was winning a war against the Republic of Venice. Henry renewed his father's friendship with Louis XII of France and signed a pact with King Ferdinand of Spain. After Pope Julius II created the anti-French Holy League in October 1511, Henry followed Spain's lead and brought England into the new League. An early joint attack by England and Spain was planned for the spring to get Aquitaine back for England, starting Henry's dream of ruling France. The attack failed and strained the alliance. Still, the French were soon pushed out of Italy, and the alliance continued, with both sides wanting more victories over the French.

On June 30, 1513, Henry invaded France. His troops defeated a French army at the Battle of the Spurs. This was a small victory, but the English used it for propaganda. Soon after, the English took Thérouanne and gave it to Maximillian. Tournai, a more important town, followed. Henry had led the army himself with a large group of followers.

However, his absence from the country led James IV of Scotland to invade England at Louis's request. The English army, led by Queen Catherine, decisively defeated the Scots at the Battle of Flodden on September 9, 1513. James IV and many important Scottish nobles died in this battle.

Charles V became king of both Spain and the Holy Roman Empire after his grandfathers, Ferdinand (1516) and Maximilian (1519), died. Francis I became king of France when Louis died in 1515. This left three relatively young rulers and a chance for a fresh start. The careful diplomacy of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey led to the Treaty of London in 1518, an early non-aggression pact among the main kingdoms of Western Europe. As a big follow-up, Henry met Francis I on June 7, 1520, at the Field of the Cloth of Gold near Calais for two weeks of fancy and very expensive entertainment.

The hope that war was over didn't last. Charles brought his Holy Roman Empire into war with France in 1521. Henry offered to help mediate, but little was achieved. By the end of the year, Henry had allied England with Charles. He still wanted to get English lands back in France. He also sought an alliance with Burgundy, then part of Charles's lands, and Charles's continued support. Charles defeated and captured Francis at Pavia and could demand peace. But he felt he owed Henry nothing. Henry had raised taxes many times to pay for his foreign actions. In 1525, quiet resistance from wealthy people forced an end to the newest tax, called the "Amicable Grant." Lack of money ended Henry's plans to invade France, and he took England out of the war with the Treaty of the More on August 30, 1525.

Exploring the New World

Just five years after Columbus, in 1497, Henry VII asked the Italian sailor John Cabot, who had settled in England, to explore the New World. Cabot was the first European since the Norsemen to reach parts of what is now Canada, exploring from Newfoundland as far south as Delaware. He found no gold or spices, and the king lost interest. Colonization was not a top priority for the Tudors. They were much more interested in raiding Spanish treasure ships than in getting their own colonies.

The Treasure Crisis of 1568

The "Treasure crisis" of 1568 happened when Queen Elizabeth seized gold from Spanish treasure ships in English ports in November 1568. Chased by privateers in the English Channel, five small Spanish ships carrying gold and silver worth £85,000 found shelter in English harbors at Plymouth and Southampton. The English government, led by William Cecil, gave permission. The money was meant for the Netherlands to pay Spanish soldiers fighting rebels there. Queen Elizabeth found out the gold was not owned by Spain, but by Italian bankers. She decided to seize it and treated it as a loan from the Italian bankers to England. The bankers agreed to her terms, so Elizabeth had the money and eventually paid the bankers back. Spain reacted angrily, seizing English property in the Netherlands and Spain. England responded by seizing Spanish ships and properties in England. Spain then stopped all English imports into the Netherlands. This bitter diplomatic standoff lasted for four years. However, neither side wanted war. In 1573, the Convention of Nymegen was a treaty where England promised to stop supporting raids on Spanish shipping by English privateers like Francis Drake and John Hawkins. It was finalized in the Convention of Bristol in August 1574, where both sides paid for what they had seized. Trade between England and Spain started again, and relations improved.

The Spanish Armada

The Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) started mostly because of religious differences. The execution of Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots in 1587 angered Spain. War was never officially declared. Spain was much stronger militarily and financially. It supported Catholic interests against England's Protestantism. The conflict involved battles far apart. It began with England's military trip in 1585 to the Spanish Netherlands (modern-day Belgium) to help the States General resist Spanish Habsburg rule. The English had a small victory by "Singeing the King of Spain's Beard" in 1587 at Cádiz, Spain's main port. The raid, led by Francis Drake, destroyed many merchant ships and captured some treasure. The great English triumph was the decisive defeat of the Spanish invasion attempt by the ill-fated Spanish Armada in 1588. After Elizabeth died in 1603, the new king made peace a top priority and ended the long conflict in 1604.

Stuart Kings (1603-1714) and Foreign Policy

By 1600, the fight with Spain was stuck during campaigns in Brittany and Ireland. James I, the new king of England, made peace with the new King of Spain, Philip III, with the Treaty of London in 1604. They agreed to stop their military actions in the Spanish Netherlands and Ireland, respectively. The English also stopped privateering against Spanish merchant ships. King James I (ruled 1603–25) truly wanted peace, not just for his three kingdoms, but for all of Europe. He disliked both Puritans and Jesuits because they were eager for war. He called himself "Rex Pacificus" ("King of peace"). Europe was deeply divided and on the edge of the huge Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). Smaller Protestant states faced aggression from larger Catholic empires. When he became king, James made peace with Catholic Spain. His policy was to marry his son to the Spanish Infanta (princess) in the "Spanish Match". The marriage of James's daughter Princess Elizabeth to Frederick V, Elector Palatine on February 14, 1613, was more than a social event. Their union had important political and military effects. Across Europe, German princes were forming the Union of German Protestant Princes, based in Heidelberg, the capital of the Palatine. King James thought his daughter's marriage would give him diplomatic influence among Protestants. He planned to have a foot in both sides and help make peaceful agreements. In his innocence, he didn't realize that both sides were using him to achieve their goal of destroying the other side. Spain's ambassador Count Gondomar knew how to manipulate the king. Catholics in Spain and Emperor Ferdinand II, the Vienna-based leader of the Habsburgs and head of the Holy Roman Empire, were strongly influenced by the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Their goal was to remove Protestantism from their lands.

Lord Buckingham (1592–1628), who increasingly ran Britain, wanted an alliance with Spain. Buckingham took Charles with him to Spain to try to win over the Infanta in 1623. However, Spain's condition was that James must end Britain's anti-Catholic intolerance or there would be no marriage. Buckingham and Charles were humiliated, and Buckingham became the leader of the widespread British demand for a war against Spain. Meanwhile, Protestant princes looked to Britain, as it was the strongest Protestant country, for military support. James's son-in-law and daughter became king and queen of Bohemia, which angered Vienna. The Thirty Years’ War began when the Habsburg Emperor removed the new king and queen of Bohemia and killed their followers. Catholic Bavaria then invaded the Palatine, and James's son-in-law begged for James's military help. James finally realized his policies had backfired and refused these pleas. He successfully kept Britain out of the European war that caused so much destruction for three decades. James's backup plan was to marry his son Charles to a French Catholic princess, who would bring a large dowry. Parliament and the British people were strongly against any Catholic marriage. They demanded immediate war with Spain and strongly favored the Protestant cause in Europe. James had angered both important people and the public in Britain, and Parliament was cutting back his money. Historians praise James for avoiding a major war at the last minute and keeping Britain at peace.

The crisis in Bohemia in 1619, and the resulting conflict, marked the start of the terrible Thirty Years' War. King James's decision to avoid getting involved in the European conflict, even during the "war fever" of 1623, seems in hindsight to be one of the most important and positive parts of his rule.

Between 1600 and 1650, England tried many times to colonize Guiana in South America. All attempts failed, and the lands (Surinam) were given to the Dutch Empire in 1667.

King Charles I (1600-1649) trusted Lord Buckingham, who became rich but failed at foreign and military policy. Charles gave him command of the military trip against Spain in 1625. It was a complete disaster, with many dying from disease and hunger. He led another terrible military campaign in 1627. Buckingham was hated, and the damage to the king's reputation was permanent. England rejoiced when he was killed in 1628 by John Felton.

Helping the Huguenots

As a major Protestant nation, England supported and helped protect Huguenots (French Protestants), starting with Queen Elizabeth in 1562. There was a small naval Anglo-French War (1627–1629), where England supported the French Huguenots against King Louis XIII of France. London paid for many Huguenots to move to England and its colonies around 1700. About 40,000-50,000 settled in England, mostly in towns near the sea in the south. The largest group was in London, where they made up about 5% of the population in 1700. Many others went to the Thirteen Colonies, especially South Carolina. The immigrants included many skilled craftspeople and business owners who helped modernize their new home's economy. The British government ignored complaints from local craftspeople about favoritism shown to foreigners. Many became private tutors, schoolmasters, and riding school owners, hired by the upper class. The immigrants fit in well, using English, joining the Church of England, marrying into English families, and succeeding in business. They started the silk industry in England.

This led to a new interest in helping people in other countries, aiming to stop foreign governments from punishing people for their religious beliefs. This new idea came largely from the good experience of protecting Huguenots in France and taking in many refugees who became good citizens.

Anglo-Dutch Wars

The Anglo-Dutch Wars were three wars between the English and the Dutch from 1652 to 1674. The reasons included political disagreements and growing competition in merchant shipping. Religion was not a factor, as both sides were Protestant. In the first war (1652–54), the British had a stronger navy with more powerful "ships of the line" that were good for the naval fighting style of the time. The British also captured many Dutch merchant ships. In the second war (1665–67), the Dutch navy won battles. This second war cost London ten times more than planned, and the king asked for peace in 1667 with the Treaty of Breda. It ended the fights over "mercantilism" (using force to protect and expand national trade, industry, and shipping). Meanwhile, the French were building fleets that threatened both the Netherlands and Great Britain. In the third war (1672–74), the British relied on a new alliance with France, but the outnumbered Dutch outsailed both of them. King Charles II ran out of money and political support. The Dutch gained control of sea trading routes until 1713. The British gained the thriving colony of New Netherland and renamed it New York.

William III: 1689–1702

The main reason the English Parliament asked William to invade England in 1688 was to overthrow King James II and stop his efforts to bring back Catholicism and allow Puritanism. However, William's main reason for accepting the challenge was to gain a powerful ally in his war to stop King Louis XIV of France's expansion. William's goal was to build alliances against the strong French monarchy, protect the independence of the Netherlands (where William remained in power), and keep the Spanish Netherlands (present-day Belgium) out of French hands. The English aristocracy strongly disliked France and usually supported William's goals. Throughout his time in the Netherlands and Britain, William was the main enemy of Louis XIV. The Catholic King of France, in turn, called the Protestant William a usurper who had illegally taken the throne from the rightful Catholic King James II, and said he should be overthrown. In May 1689, William, now king of England, with Parliament's support, declared war on France.

Historian J.R. Jones states that King William was given:

- supreme command within the alliance throughout the Nine Years War. His experience and knowledge of European affairs made him the essential leader of Allied diplomatic and military strategy, and he gained more authority from his higher status as king of England – even the Emperor Leopold...recognized his leadership. William's English subjects played smaller roles in diplomatic and military affairs, having a major share only in leading the war at sea. Parliament and the nation had to provide money, men, and ships, and William found it helpful to explain his plans...but this did not mean that Parliament or even ministers helped create policy.

England and France were almost constantly at war until 1713, with a short break from 1697–1701 made possible by the Treaty of Ryswick. The combined English and Dutch fleets could defeat France in a widespread naval war, but France still had stronger armies on land. William wanted to cancel that advantage by allying with Leopold I, the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor (1658–1705), who was based in Vienna. Leopold, however, was busy with a war against the Ottoman Empire on his eastern borders. William worked to achieve a negotiated settlement between the Ottomans and the Empire. William showed an imaginative strategy across Europe, but Louis always managed to find a counter-move.

William was usually supported by English leaders, who saw France as their biggest enemy. But eventually, the costs and war weariness caused second thoughts. At first, Parliament gave him the money for his expensive wars and for his payments to smaller allies. Private investors created the Bank of England in 1694. It provided a stable system that made financing wars much easier by encouraging bankers to lend money.

In the long Nine Years' War (1688–97), his main strategy was to form a military alliance of England, the Netherlands, the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and some smaller states. This alliance would attack France at sea and from land in different directions, while defending the Netherlands. Louis XIV tried to weaken this strategy by refusing to recognize William as king of England. He also gave diplomatic, military, and financial support to various people who claimed the English throne, all based in France. William focused most of his attention on foreign policy and foreign wars, spending a lot of time in the Netherlands (where he continued to hold the main political office). His closest foreign-policy advisers were Dutch, especially William Bentinck, 1st Earl of Portland. They shared little information with their English counterparts. The result was that the Netherlands remained independent, and France never took control of the Spanish Netherlands. The wars were very expensive for both sides but didn't have a clear winner. William died just as the next war, the War of the Spanish Succession (1702–1714), was beginning. It was fought during Queen Anne's reign and ended in a draw.

Wars with France (1702–1815)

Britain's Diplomatic Service

Unlike major rivals like France, the Netherlands, Sweden, or Austria, Britain's control over its own diplomacy was inconsistent. Diplomats were often poorly chosen, poorly funded, and not professional. The main posts were Paris and The Hague, but the diplomats sent there were better at dealing with London politics than with international affairs. King William III handled foreign policy himself, using Dutch diplomats whenever possible. After 1700, Britain increased the number of its diplomatic staff in major capitals, without much focus on quality. Vienna and Berlin were given more importance, but even they were ignored for years at a time. By the 1790s, British diplomats had learned a lot by closely watching their French rivals. Aristocratic exiles from Paris also started helping. For the first time in the French wars, Britain set up a secret intelligence service that was in contact with local rebels and helped shape their protests. William Pitt the Younger, the Prime Minister during much of the French Revolutionary period, had a largely incompetent Foreign Secretary, Francis Osborne, 5th Duke of Leeds, from 1783 to 1791. However, Pitt managed to bring in many strong diplomats, such as James Harris at The Hague, where he formed an alliance that, with Prussia, became a triple alliance in 1788. Pitt often used him to solve problems in difficult negotiations. Pitt brought in William Eden (1744–1814), who negotiated a tough trade treaty with France in 1786.

Pitt also brought in three foreign ministers with strong reputations. William Grenville (1791–1801) saw France as a huge threat to every nation in Europe. He focused on defeating it, working closely with his cousin, Prime Minister Pitt. George Canning (1807–9) and Viscount Castlereagh (1812–15) were very successful in organizing complex alliances that eventually defeated Napoleon. Castlereagh and Canning showed imagination and energy, even though their personalities clashed so much they fought a duel.

Britain's leaders understood the importance of the growing Royal Navy. They made sure that in various treaties, Britain gained naval bases and access to key ports. In the Mediterranean, it controlled Gibraltar and Minorca, and had good positions in Naples and Palermo. The alliance with Portugal in 1703 protected its access to the Mediterranean. In the North, Hanover played a role (it was ruled by the English king), while the alliance with Denmark gave naval access to the North Sea and the Baltic. Meanwhile, French sea power was weakened by the Treaty of Utrecht, which forced France to destroy its naval base in Dunkirk. English sea power was boosted by a series of trade treaties, including those of 1703 with Portugal, and with the Netherlands, Savoy, Spain, and France in 1713. Although London merchants had little direct say at the royal court, the king valued their contribution to his kingdom's wealth and tax income.

War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1712)

Britain was a player in the first world war of modern times, with fighting in Spain, Italy, Germany, Holland, and at sea. The main issue was the threat of a French-supported Bourbon heir becoming king of Spain. This would allow the Bourbon kings of France to control Spain and its American empire.

Queen Anne was in charge, but she relied on an experienced team of experts, generals, diplomats, cabinet members, and War Office officials—most notably her most successful general John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough. He is best known for his great victory at the Battle of Blenheim in 1704. In 1706, he defeated the French at the Battle of Ramillies, captured their garrisons, and drove the French out of most of the Spanish Netherlands. The Royal Navy, with help from the Dutch, captured Gibraltar in 1704-5, which has been key to British power in the Mediterranean ever since. The war dragged on, and neither France nor England could afford the rising costs. So, a compromise was finally reached in the Treaty of Utrecht. This treaty protected most of England's interests. The French gave up their long-term claim that the Old Pretender (the Catholic son of James II by his second marriage) was the true King of England. Utrecht marked the end of French ambitions to dominate Europe, which were seen in the wars of Louis XIV. It also preserved the European system based on the balance of power. British historian G. M. Trevelyan argues:

That Treaty, which ushered in the stable and characteristic period of Eighteenth-Century civilization, marked the end of danger to Europe from the old French monarchy, and it marked a change of no less significance to the world at large, — the maritime, commercial and financial supremacy of Great Britain.

England solved its long-standing problem with Scotland in the Acts of Union 1707. This brought Scotland into the British political and economic system. The much smaller Scotland kept its traditional political leaders, its established Presbyterian church, its excellent universities, and its unique legal system. The War of the Spanish Succession had again shown the danger of an independent Scotland allied with France, acting as a threat to England. Awareness of this danger helped decide the timing, manner, and results of the union. Scots began to play major roles in British intellectual life and in providing diplomats, merchants, and soldiers for the growing British Empire.

War of the Austrian Succession (1742–48)

Britain played a small part in this inconclusive but hard-fought war that affected central Europe, while funding its ally Austria. The goal, as set by foreign minister John Carteret, was to limit the growth of French power and protect the Electorate of Hanover, which was also ruled by King George II. In 1743, King George II led a 40,000-man British-Dutch-German army into the Rhine Valley. He was outsmarted by the French Royal Army but scored a narrow victory at the Battle of Dettingen. In the winter of 1743–44, the French planned to invade Britain with the Stuart pretender to George's throne. They were stopped by the Royal Navy. King George gave command to his son the Duke of Cumberland. He did poorly, and Britain pulled out of the war to deal with a rebellion at home. There, Cumberland gained fame by decisively stopping the Jacobite Rising at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. Meanwhile, Britain did much better in North America, capturing the strong Fortress of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748) favored France, which won most victories. Britain returned the Fortress of Louisbourg to France, and the French left the Austrian Netherlands (modern Belgium). Prussia and Savoy were the main winners, and Britain's ally Austria was a loser. The treaty left the main issues of control over territories in America and India unresolved. It was little more than a temporary peace and a prelude to the more important Seven Years' War.

Seven Years' War (1754–63)

The Seven Years' War (1756–63 in Europe, 1754–63 in North America) was a major international conflict centered in Europe but reaching across the globe. Great Britain and Prussia were the winners. They fought France, Austria, Spain, and Russia—nearly all other important powers except the Ottoman Empire. The Royal Navy played a major role, and the army and the Treasury played important roles. The war seemed like a disaster for Prussia until its luck changed at the last second. Britain took much of the overseas French Empire in North America and India. How the war was paid for was a critical issue. Britain handled it well, and France handled it poorly, getting so deep in debt that it never fully recovered. William Pitt (1708–78) energized British leadership and used effective diplomacy and military strategy to win. Britain used manpower from its American colonies effectively with its regular soldiers and Navy to overwhelm the much less populated French colonial empire in what is now Canada. From a small spark in 1754 in the distant wilderness (the Battle of Fort Necessity near modern-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania), the fighting spread to Europe. 1759 was the "annus mirabilis" ("miraculous year"), with victory after victory. British and Prussian troops defeated the French army at the Battle of Minden. The British captured Guadeloupe Island and Quebec, crushed the French fleet at Quiberon Bay, and (in January 1760) defeated the French in southern India. Peace terms were hard to reach, and the war dragged on until everyone was exhausted. The British national debt soared to £134 million from £72 million, but London had a financial system that could handle the burden.

A debate happened at the peace conference about whether Britain should keep the French colony of "New France" (now Canada) or Guadeloupe, both of which it had seized in the war. France wanted the rich sugar island as its world view turned to sea and tropical interests. Meanwhile, Britain was moving from trade and sea rules to taking direct control over its colonies. So Britain kept the vast, less profitable lands of Canada, and France kept the rich little island.

American War of Independence (1775–83)

Neutral Countries

Britain's diplomacy failed in the war. It only had support from a few small German states that hired out soldiers. Most of Europe was officially neutral, but important people and the public usually favored the underdog American Patriots, as in Sweden and Denmark.

The League of Armed Neutrality was an alliance of smaller European naval powers between 1780 and 1783. It aimed to protect neutral shipping against the Royal Navy's wartime policy of searching neutral ships for French contraband. Empress Catherine II of Russia started the League in 1780. She supported the right of neutral countries to trade by sea with warring countries without problems, except for weapons and military supplies. The League would not recognize blockades of entire coasts, only of individual ports, and only if a British warship was actually present. Denmark and Sweden agreed with Russia, and the three countries signed the agreement forming the League. They stayed out of the war otherwise but threatened joint retaliation for every ship of theirs searched by a warring country. By the end of the war in 1783, Prussia, the Holy Roman Empire, the Netherlands, Portugal, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and the Ottoman Empire had all joined.

The League never fought a battle. Diplomatically, it had more influence. France and the United States quickly said they agreed with the new rule of free neutral trade. Britain—which did not—still didn't want to anger Russia and avoided interfering with the allies' shipping. While both sides of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War quietly understood it as an attempt to keep the Netherlands out of the League, Britain did not officially see the alliance as hostile.

William Pitt the Younger

As Prime Minister (1783–1801, 1804–1806), William Pitt the Younger, despite his youth, revitalized Great Britain's government system, modernized its finances, and led the way out of the diplomatic isolation it found itself in during the American war. Starting in 1793, he led the British nation in its deadly fight against the French Revolution and Napoleon.

Warfare and Money

From 1700 to 1850, Britain was involved in 137 wars or rebellions. It kept a large and expensive Royal Navy, along with a small standing army. When more soldiers were needed, it hired mercenaries or paid allies who had armies. The rising costs of war forced a change in government funding. It shifted from income from royal farms and special taxes to relying on customs and excise taxes and, after 1790, an income tax. Working with bankers in the City, the government raised large loans during wartime and paid them off in peacetime. The increase in taxes amounted to 20% of national income, but the private sector benefited from increased economic growth. The demand for war supplies boosted the industrial sector, especially naval supplies, weapons, and textiles, which gave Britain an advantage in international trade after the war. In the 1780s, Pitt reformed the financial system by raising taxes, carefully watching expenses, and setting up a sinking fund to pay off the long-term debt, which was £243 million, with annual interest taking up most of the budget. Meanwhile, the banking system used its ownership of the debt to provide money for economic growth. When the wars with France began, the debt reached £359 million in 1797. Pitt kept the sinking fund going and raised taxes, especially on luxury items. Britain was far ahead of France and all other powers in using finance to strengthen its economy, military, and foreign policy.

Nootka Crisis with Spain (1789–1795)

The Nootka Crisis was a problem with Spain that started in 1789 at Nootka Sound, an unsettled area now part of British Columbia. Spain seized small British merchant ships involved in the fur trade on the Pacific Ocean along the Pacific Coast. Spain claimed ownership based on a papal decree from 1493 that Spain said gave it control of the entire Pacific Ocean. Britain rejected Spain's claims and used its much stronger naval power to threaten war and win the dispute. Spain, a rapidly weakening military power, could not rely on its long-time ally France, which was struggling with internal revolution. The dispute was settled by negotiations in 1792–94, which became friendly when Spain switched sides in 1792 and allied with Britain against France. Spain gave up many of its trade and land claims in the Pacific to Britain, ending a two-hundred-year monopoly on Asian-Pacific trade. The outcome was a victory for Britain's trade interests and opened the way for British expansion in the Pacific.

French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1803)

The French Revolution began in 1789 and divided British political opinion. The ruling conservatives were outraged by the killing of the king, the expulsion of nobles, and the Reign of Terror. Britain was at war against France almost continuously from 1793 until the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815. The goal was to stop the spread of revolutionary and democratic ideas and prevent France from controlling Western Europe. William Pitt the Younger was the main leader until his death in 1806. Pitt's strategy was to gather and fund the alliance against France. It seemed too hard to attack France on the continent, so Pitt decided to seize France's valuable colonies in the West Indies and India. At home, a small pro-French group had little influence with the British government. Conservatives criticized every radical idea as "Jacobin" (referring to the leaders of the Terror), warning that radicalism threatened to upset British society.

- 1791–92: London rejects getting involved in the French Revolution. Its policy is based on what's practical, not ideology. It seeks to avoid French attacks on the Austrian Netherlands, not worsen the fragile situation of King Louis XVI, and prevent a strong alliance forming in Europe.

- 1792–97: War of the First Coalition: Prussia and Austria, joined after 1793 by Britain, Spain, the Netherlands, Sardinia, Naples, and Tuscany, fight against the French Republic.

- 1792: Austria and Prussia invade France. The French defeat the invaders and then go on the attack, invading the Austrian Netherlands (modern Belgium) in late 1792. This causes serious tension with Britain, as it was British policy to ensure France could not control the "narrow seas" by keeping the French out of the Low Countries.

- 1792: In India, victory over Tipu Sultan in the Third Anglo-Mysore War; half of Mysore is given to the British and their allies.

- 1793: France declares war on Britain.

- 1794: Jay Treaty with the United States normalizes trade and ensures a decade of peace. The British withdraw from forts in the Northwest Territory but continue to support tribes hostile to the U.S. France is angered by the close relationship and says the Jay Treaty violates its 1777 treaty with the U.S.

- 1802–03: Peace of Amiens allows 13 months of peace with France.

Defeating Napoleon (1803–1814)

Britain ended the uneasy peace created by the Treaty of Amiens when it declared war on the First French Empire in May 1803. The British were increasingly angered by Napoleon's changes to the international system in Western Europe, especially in Switzerland, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands.

Britain felt it was losing control and markets. It was also worried by Napoleon's possible threat to its overseas colonies. Frank McLynn argues that Britain went to war in 1803 due to "a mix of economic reasons and national fears – an irrational worry about Napoleon's motives and plans." McLynn concludes that in the long run, it was the right choice for Britain, because Napoleon's intentions were hostile to British interests. Napoleon was not ready for war, so this was the best time for Britain to stop him. Britain focused on the Malta issue, refusing to follow the Treaty of Amiens and leave the island.

The deeper British complaint was their feeling that Napoleon was taking personal control of Europe, making the international system unstable, and pushing Britain aside.

Historian G. M. Trevelyan argues that British diplomacy under Lord Castlereagh played a decisive role:

- In 1813 and 1814 Castlereagh played the part that William III and Marlborough had played more than a hundred years before, in holding together an alliance of jealous, selfish, weak-kneed states and princes, by a vigor or character and singleness of purpose that held Metternich, the Czar and the King of Prussia on the common track until the goal was reached. It is quite possible that, but for the lead taken by Castlereagh in the allied counsels, France would never have been reduced to her ancient limits, nor Napoleon dethroned.

- 1803: Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) against France begin.

- 1803–06: War of the Third Coalition: Napoleon ends the Holy Roman Empire.

- 1803: Through an Anglo-Russian agreement, Britain pays £1.5 million for every 100,000 Russian soldiers fighting. Money also went to Austria and other allies.

- 1804: Pitt organizes the Third Coalition against Napoleon; it lasts until 1806 and is mostly marked by French victories.

- 1805: Decisive defeat of the French navy at the Battle of Trafalgar by Nelson; end of invasion threats.

- 1806–07: Britain leads the Fourth Coalition in alliance with Prussia, Russia, Saxony, and Sweden. Napoleon leads France to victory at many major battles, notably Battle of Jena–Auerstedt.

- 1807: Britain makes the international slave trade illegal; Slave Trade Act 1807. The US prohibits the importation of new slaves (Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves).

- 1808–14: Peninsular War against Napoleonic forces in Spain; results in victory under the Duke of Wellington.

- 1812–15: US declares War of 1812 over national honor, neutral rights at sea, and British support for western Indians.

- 1813: Napoleon defeated at Battle of the Nations; he retreats.

- 1814: France invaded; Paris falls; Napoleon gives up his throne and the Congress of Vienna begins.

- 1814: Anglo-Nepalese War (1814–1816).

- 1815: With the War of 1812 against the U.S. a military draw, the British abandon their First Nation allies and agree at the Treaty of Ghent to restore things to how they were before the war. This begins a lasting peace along the US-Canada border, only disturbed by occasional small, unauthorized raids.

- 1815: Napoleon returns and for 100 days is again a threat; he is defeated at the Battle of Waterloo and sent away to the distant island of Saint Helena.

- 1815: The Napoleonic Wars end, marking the start of Britain's Imperial Century, 1815–1914.

- 1815: Second Kandyan War (1815) – in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

The "British Peace" (1814–1914)

The main purpose of the British defense system, especially the Royal Navy, was to protect its overseas empire and defend the homeland. The army, usually with local forces, stopped internal revolts, losing only the American War of Independence (1775–83). David Armitage says it became a British belief that:

Protestantism, ocean trade, and control of the seas provided strongholds to protect the freedom of people in the British Empire. That freedom was shown in Parliament, the law, property, and rights, all of which were sent throughout the British Atlantic world. Such freedom also allowed the British, uniquely, to combine the traditionally opposite ideas of liberty and empire.

Away from the high seas, Britain's involvement in India and exaggerated fears of Russian intentions led to involvement in the Great Game rivalry with the Russian Empire.

Britain, with its global empire, powerful Navy, leading industries, and unmatched financial and trade networks, dominated diplomacy in Europe and the world during the mostly peaceful century from 1814 to 1914. Five men stood out for their leadership in British foreign policy: Lord Palmerston, Lord Aberdeen, Benjamin Disraeli, William Gladstone, and Lord Salisbury. Open military action was much less important than diplomacy. British military actions from 1815–50 included opening markets in Latin America (like in Argentina), opening the China market, responding to humanitarians by sending the Royal Navy to stop the Atlantic slave trade, and building a balance of power in Europe, as in Spain and Belgium.

Key Leaders in Foreign Policy

Lord Palmerston

Lord Palmerston, first as a Whig and then as a Liberal, became the main leader in British foreign policy for most of the period from 1830 until his death in 1865. As Foreign Secretary (1830-4, 1835–41, and 1846–51) and later as prime minister, Palmerston tried to keep the balance of power in Europe, sometimes opposing France and at other times allying with France to do so. For example, he allied Britain with France in the Crimean War against Russia. The allies fought and won this war with the limited goal of protecting the Ottoman Empire. Some of his aggressive actions, now sometimes called "liberal interventionist", were very controversial at the time and still are today. For example, he used military force to achieve his main goal of opening China to trade. In all his actions, Palmerston showed great patriotic energy. This made him very popular among ordinary British people, but his passion, tendency to act based on personal dislike, and bossy language made him seem dangerous and destabilizing to the Queen and his more conservative colleagues in government. He was an innovative administrator who found ways to increase his control over his department and build his reputation. He controlled all communication within the Foreign Office and to other officials. He leaked secrets to the press, published selected documents, and released letters to gain more control.

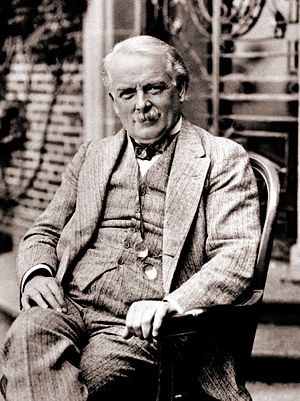

Lord Aberdeen

Lord Aberdeen (1784-1860) was a very successful diplomat in many disputes from 1812 to 1856, but he failed badly in handling the Crimean War and retired in 1856. In 1813-1814, as ambassador to the Austrian Empire, he negotiated the alliances and funding that led to Napoleon's defeat. In Paris, he normalized relations with the newly restored Bourbon government and convinced London that the Bourbons could be trusted. He worked well with top European diplomats like his friends Klemens von Metternich in Vienna and François Guizot in Paris. He brought Britain into the center of European diplomacy on important issues, such as the local wars in Greece, Portugal, and Belgium. Ongoing problems with the United States were ended by compromising the border dispute in Maine. This gave most of the land to the Americans but gave Canada important links to a warm-water port. He played a central role in winning the First Opium War against China, gaining control of Hong Kong in the process.

Benjamin Disraeli

Benjamin Disraeli, the Conservative leader for much of the mid-19th century, built up the British Empire and played a major role in European diplomacy. Disraeli's second term as Prime Minister (1874–1880) was dominated by the Eastern Question—the slow decline of the Ottoman Empire and the desire of other European powers, like Russia, to gain land from the Ottomans. Disraeli arranged for the British to buy (1875) a major share in the Suez Canal Company (in Ottoman-controlled Egypt). In 1878, facing Russian victories against the Ottomans, he worked at the Congress of Berlin to achieve peace in the Balkans on terms favorable to Britain and unfavorable to Russia, its long-time enemy. This diplomatic victory over Russia made Disraeli one of Europe's leading statesmen. However, world events then turned against the Conservative Party. Controversial wars in Afghanistan (1878-1880) and in South Africa (1879) weakened Disraeli's public support.

William Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone (Prime Minister 1868–74, 1880–85, 1886, 1892–94), the Liberal Party leader, was much less interested in imperialism than Disraeli. He sought peace as the highest foreign-policy goal. However, historians have been very critical of Gladstone's foreign policy during his second time as prime minister. Paul Hayes says it "provides one of the most interesting and confusing stories of confusion and incompetence in foreign affairs, unmatched in modern political history until the days of Grey and, later, Neville Chamberlain." Gladstone opposed the "colonial lobby" which pushed for the scramble for Africa. His term saw the end of the Second Anglo-Afghan War in 1880, the First Boer War of 1880-1881, and the start of the war (1881-1899) against the Mahdi in Sudan.

Lord Salisbury

Historians generally see Lord Salisbury (Foreign Minister 1878–80, 1885–86, 1887–92, and 1895–1900, and Prime Minister 1885-6, 1886–92, 1895–1902) as a strong and effective leader in foreign affairs. Historians in the late 20th century rejected the older idea that Salisbury followed a policy of "splendid isolation" (staying out of European alliances). He had an excellent understanding of the issues and proved to be:

- a patient, practical leader, with a sharp understanding of Britain's historical interests....He oversaw the division of Africa, the rise of Germany and the United States as imperial powers, and the shift of British attention from the Dardanelles to Suez without causing a serious conflict among the great powers.

Free Trade and Empire

The Great Exhibition of 1851 clearly showed Britain's dominance in engineering and industry. This lasted until Germany and the United States rose in the 1890s. Using free trade and financial investment as tools of empire, Britain had a major influence on many countries outside Europe, especially in Latin America and Asia. So Britain had both a formal Empire (where it ruled directly) and an informal one (where its financial power was key).

Relations with Latin America

The independence of Latin American countries, especially after 1826, opened profitable opportunities for London bankers. The region was badly damaged by the wars of independence and had weak financial systems, weak governments, and repeated coups and internal rebellions. However, the region had a well-developed export sector focused on foods in demand in Europe, especially sugar, coffee, wheat, and (after refrigeration arrived in the 1860s) beef. There was also a well-developed mining sector. With the Spanish gone, ex-Spanish America in the early 1820s was a devastated region suffering a deep economic downturn. It urgently needed money, entrepreneurs, bankers, and shippers. British entrepreneurs quickly filled the gap by the mid-1820s, as the London government used its diplomatic power to encourage large-scale investment. The Royal Navy protected against piracy. The British set up communities of merchants in major cities—including 3,000 Britons in Buenos Aires. London bankers bought £17 million in Latin American government bonds, especially from Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Mexico. They invested another £35 million in 46 stock companies set up to operate mainly in Latin America. The bubble soon burst, but the surviving companies operated quietly and profitably for many decades. From the 1820s to the 1850s, over 260 British merchant houses operated in the River Plate or Chile, and hundreds more in the rest of Latin America. The Latin American market was important for the cotton manufacturers of Lancashire. They supported the independence movement and persuaded the British government to place commercial consuls in all major trading centers in Latin America. The British were permanently committed, and it took decades—until the 1860s—before the commercial involvement paid serious dividends. By 1875, Latin America was firmly connected to a transatlantic economy under British leadership. After 1898, the British had to compete commercially with the United States.

Over the long term, Britain's influence in Latin America was huge after independence was established in the 1820s. Britain deliberately tried to replace Spain in economic and cultural matters. Military issues and colonization were minor factors. British influence worked through diplomacy, trade, banking, and investment in railways and mines. The English language and British cultural norms were spread by energetic young British business agents on temporary assignments in major commercial centers. There, they invited locals to British leisure activities, such as organized sports, and to their transplanted cultural institutions like clubs and schools. The impact on sports was enormous as Latin America enthusiastically took up football (soccer). In Argentina, rugby, polo, tennis, and golf became important for middle-class leisure. Cricket was ignored. The British role never disappeared, but it faded quickly after 1914 as the British sold their investments to pay for World War I (1914-1918). The United States then moved into the region with overwhelming force and similar cultural norms.

No actual wars in 19th-century Latin America directly involved Britain. However, several confrontations occurred. The most serious came in 1845–1850 when British and French navies blockaded Buenos Aires to protect Uruguay's independence from Juan Manuel de Rosas, the dictator of Argentina. Other smaller disputes with Argentina broke out in 1833, with Guatemala in 1859, Mexico in 1861, Nicaragua in 1894, and Venezuela in 1895 and 1902. There was also tension along the Mosquito Coast in Central America in the 1830s and 1840s.

Relations with the United States

British relations with the United States often became tense and even close to armed conflict. Britain almost supported the Confederacy in the early part of the American Civil War of 1861-1865. British leaders were constantly annoyed from the 1840s to the 1860s by what they saw as Washington's efforts to please the democratic public, as in the Oregon boundary dispute in 1844–46. However, British middle-class public opinion felt a common "Special Relationship" between the two peoples based on language, migration, Protestantism, liberal traditions, and extensive trade. This group rejected war, forcing London to calm the Americans. During the Trent affair in late 1861, London drew the line, and Washington backed down.

British public opinion was divided on the American Civil War. The Confederacy tended to have support from the elites—from the aristocracy and gentry, who identified with the landed plantation owners, and from Anglican clergy and some professionals who admired tradition, hierarchy, and paternalism. The Union was favored by the middle classes, the Nonconformists in religion, intellectuals, reformers, and most factory workers, who saw slavery and forced labor as a threat to the status of the workingman. The cabinet made the decisions. Chancellor of the Exchequer William E Gladstone, whose family fortune was based on slave plantations in the West Indies, supported the Confederacy. Foreign Minister Lord Russell wanted neutrality. Prime Minister Lord Palmerston wavered between support for national independence, his opposition to slavery, and the strong economic advantages of Britain remaining neutral.

Britain supplied warships and blockade runners to the Confederate Navy, but also had large-scale trade with the United States. Many British men volunteered to fight for the Northern Union Army. Northern food supplies were much more essential to Britain than Southern cotton. After the war, the US demanded payments (called the Alabama Claims) for the damages caused by the warships. After arbitration, the British paid the U.S. $15.5 million in 1872, and peaceful relations resumed.

Relations with the Ottoman Empire

As the 19th century went on, the Ottoman Empire grew weaker, and Britain increasingly became its protector. Britain even fought the Crimean War in the 1850s to help it against Russia. Three British leaders played major roles. Lord Palmerston, in the 1830–65 era, thought the Ottoman Empire was an essential part of the balance of power and was the most supportive of Constantinople. William Gladstone, in the 1870s, tried to build a "Concert of Europe" that would support the empire's survival. In the 1880s and 1890s, Lord Salisbury considered an orderly breakup of the empire in a way that would reduce rivalry between the greater powers.

Crimean War (1854–56)

The Crimean War (1854–56) was fought between Russia on one side and an alliance of Britain, France, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire on the other. Russia was defeated, but casualties were very high on all sides, and historians see the whole event as a series of mistakes.

The war began with Russian demands to protect Christian sites in the Holy Land. The churches quickly settled that problem, but it grew out of control as Russia put continuous pressure on the Ottomans. Diplomatic efforts failed. The Sultan declared war against Russia in October 1851. After an Ottoman naval disaster in November, Britain and France declared war against Russia. It was quite difficult to reach Russian territory, and the Royal Navy could not defeat the Russian defenses in the Baltic. Most of the battles took place in the Crimean peninsula, which the Allies finally captured. London was shocked to find out that France was secretly negotiating with Russia to form a postwar alliance to dominate Europe. Britain dropped its plans to attack St. Petersburg and instead signed a one-sided truce with Russia that achieved almost none of its war goals.

The Treaty of Paris, signed March 30, 1856, ended the war. Russia gave up a little land and dropped its claim to protect Christians in the Ottoman lands. The Black Sea was demilitarized (no military forces allowed), and an international commission was set up to guarantee freedom of commerce and navigation on the Danube River. Moldavia and Wallachia remained under nominal Ottoman rule but would be granted independent constitutions and national assemblies. However, by 1870, the Russians had regained most of their concessions.

The war helped modernize warfare by introducing major new technologies like railways, the telegraph, and modern nursing methods. In the long run, the war marked a turning point in Russian domestic and foreign policy. Russian thinkers used the defeat to demand major reforms of the government and social system. The war weakened Russia and diplomatically isolated Austria, so they could no longer promote stability. This opened the way for Napoleon III, Cavour (in Italy), and Otto von Bismarck (in Germany) to start a series of aggressive wars in the 1860s that reshaped Europe.

Of the 91,000 British soldiers and sailors sent to Crimea, 21,000 died, 80 percent of them from disease. The losses were reported in detail in the media and caused disgust against warfare in Britain, combined with a celebration of the heroic common soldier who showed Christian virtue. The great heroine was Florence Nightingale, who was praised for her dedication to caring for the wounded and her focus on middle-class efficiency. She represented a moral status as a nurse that was superior to aristocratic militarism in terms of both morality and efficiency.

Historian R. B. McCallum points out the war was enthusiastically supported by the British public as it was happening, but the mood changed very dramatically afterward. Pacifists and critics were unpopular but:

in the end they won. Cobden and Bright were true to their principles of foreign policy, which laid down the absolute minimum of intervention in European affairs and a deep moral disapproval of war....When the first enthusiasm was passed, when the dead were mourned, the sufferings revealed, and the cost counted, when in 1870 Russia was able calmly to secure the revocation of the Treaty, which disarmed her in the Black Sea, the view became general that the war was stupid and unnecessary, and achieved nothing....The Crimean war remained as a classic example...of how governments may rush into war, how strong ambassadors may mislead weak prime ministers, how the public may be worked up into an easy fury, and how the achievements of the war may crumble to nothing. The Bright-Cobden criticism of the war was remembered and to a large extent accepted [especially by the Liberal Party]. Staying out of European problems seemed more desirable than ever.

Taking Control of Egypt (1882–1914)

The most important event came from the Anglo-Egyptian War, which led to Britain occupying the Khedivate of Egypt. Although the Ottoman Empire was the official owner, in practice Britain made all the decisions. In 1914, Britain went to war with the Ottomans and ended their official role. Historian A. J. P. Taylor says that the seizure, which lasted seven decades, "was a great event; indeed, the only real event in international relations between the Battle of Sedan and the defeat of Russia and the Russo-Japanese war." Taylor emphasizes the long-term impact:

- The British occupation of Egypt changed the balance of power. It not only gave the British security for their route to India; it made them masters of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East; it made it unnecessary for them to stand in the front line against Russia at the Straits....And thus prepared the way for the Franco-Russian Alliance ten years later.

Early 1900s (1900–1914)

After 1900, Britain ended its policy of "splendid isolation" (staying out of alliances) by developing friendly relations with the United States and European powers—most notably France and Russia, in an alliance that fought the First World War. The "Special Relationship" with the United States, starting around 1898, allowed Britain to largely move its naval forces out of the Western Hemisphere.

According to G. W. Monger's summary of the Cabinet debates in 1900 to 1902:

Chamberlain suggested ending Britain's isolation by making an alliance with Germany; Salisbury resisted change. With the new crisis in China caused by the Boxer rising and Landsdowne's appointment to the Foreign Office in 1900, those who wanted a change gained power. Landsdowne in turn tried to reach an agreement with Germany and a settlement with Russia but failed. In the end, Britain made an alliance with Japan. The decision of 1901 was very important; British policy had been guided by events, but Lansdowne didn't truly understand these events. The change of policy had been forced on him and was an admission of Britain's weakness.

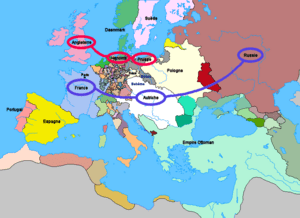

Germany's Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had controlled European diplomacy from 1872–1890, aiming to use the balance of power to keep the peace. There were no wars. However, he was removed by an aggressive young Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1890, allowing French efforts to isolate Germany to succeed. Joseph Chamberlain, who played a major role in foreign policy in the late 1890s under the Salisbury government, repeatedly tried to start talks with Germany about some kind of alliance. Germany was not interested. Instead, Berlin felt increasingly surrounded by France and Russia. Meanwhile, Paris went to great lengths to win over Russia and Great Britain. Key agreements were the Franco-Russian Alliance of 1894, the 1904 Entente Cordiale linking France and Great Britain, and finally the Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907, which became the Triple Entente. France thus had a formal alliance with Russia and an informal alignment with Britain, against Germany. By 1903, Britain had established good relations with the United States and Japan.

Britain abandoned the policy of staying away from European powers ("Splendid Isolation") in the 1900s after standing without friends during the Second Boer War (1899–1903). Britain made agreements, limited to colonial affairs, with its two major colonial rivals: the Entente Cordiale with France in 1904 and the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907. Britain's alignment was a reaction to an assertive German foreign policy and the buildup of its navy from 1898, which led to the Anglo-German naval arms race. British diplomat Arthur Nicolson argued it was "far more disadvantageous to us to have an unfriendly France and Russia than an unfriendly Germany". The impact of the Triple Entente was to improve British relations with France and its ally Russia and to make good relations with Germany less important to Britain. After 1905, foreign policy was tightly controlled by the Liberal foreign minister Edward Grey (1862–1933), who rarely consulted the Cabinet. Grey shared the strong Liberal policy against all wars and against military alliances that would force Britain to take a side in war. However, in the case of the Boer War, Grey believed that the Boers had committed an aggression that needed to be stopped. The Liberal party split on the issue, with a large group strongly opposed to the war in Africa.

The Triple Entente between Britain, France, and Russia is often compared to the Triple Alliance between Germany, Austria–Hungary, and Italy, but historians warn against the comparison. The Entente, unlike the Triple Alliance or the Franco-Russian Alliance, was not an alliance of mutual defense. Britain therefore felt free to make its own foreign policy decisions in 1914. The Liberal party members were very peaceful and moralistic. By 1914, they were increasingly convinced that German aggression violated international rules, and specifically that a German invasion of neutral Belgium was completely wrong. However, the all-Liberal British cabinet decided on July 29, 1914, that being a signatory to the 1839 treaty about Belgium did not obligate it to oppose a German invasion of Belgium with military force. As war neared, the cabinet agreed that Germany defeating France and controlling the continent of Europe was unacceptable and would be a reason for war.

After 1805, the dominance of Britain's Royal Navy was unchallenged. In the 1890s, Germany decided to try to match it. Grand Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (1849–1930) controlled German naval policy from 1897 until 1916. Before the German Empire formed in 1871, Prussia never had a real navy, nor did the other German states. Tirpitz turned the small fleet into a world-class force that could threaten the British Royal Navy. The British responded with new technology, like the Dreadnought revolution. This made every battleship obsolete. Along with a global network of coaling stations and telegraph cables, it allowed Britain to stay well ahead in naval affairs.

Around the same time, Britain started using fuel oil in warships instead of coal. The benefits of oil for the navy were significant. It made ships cheaper to build and run, gave them greater range, and removed strategic limits caused by needing frequent stops at coaling stations. Britain had plenty of coal but no oil and had relied on American and Dutch oil suppliers. So, its foreign policy made securing oil a high priority. At the suggestion of Admiral John Fisher, Winston Churchill addressed this, starting with the Royal Commission on Fuel and Engines of 1912. The issue became urgent when it was learned that Germany was arranging an oil supply in the Middle East. Britain secured its own supplies through foreign policy and its 1914 purchase of a controlling, 51% stake in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, which BP is a successor to.

First World War (1914-1918)

Besides providing soldiers and fleets, one of Britain's most important roles was financing the war. It gave large loans and grants to France, Russia, Italy, and others. It tried to stay friendly with the United States, which sold large amounts of raw materials and food and provided large loans. Germany was so convinced that the United States, as a neutral country, was playing a decisive role that it began unrestricted submarine warfare against the United States. Germany knew this would lead to American entry into the war in April 1917. The United States then took over Britain's financial role, lending large sums to Britain, France, Russia, Italy, and the others. The US demanded repayment after the war but did negotiate better terms for Britain. Finally, in 1931, all debt payments were stopped.

Between the World Wars (1919–1939)

Britain had suffered little destruction during the war. Prime Minister David Lloyd George supported reparations (payments for war damage) to a lesser extent than the French did at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. Britain reluctantly supported the harsh Treaty of Versailles, while the U.S. rejected it. France was the main supporter in its quest for revenge.

Strong memories of the horrors and deaths of the World War made Britain and its leaders very inclined to pacifism (opposition to war) in the years between the wars.

Britain was a "troubled giant," having much less influence than before. It often had to give way to the United States, which frequently used its financial superiority. The main goals of British foreign policy included a conciliatory role at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, where Lloyd George worked hard to lessen French demands for revenge. He was partly successful, but Britain soon had to moderate French policy toward Germany, as in the Locarno Treaties. Britain was an active member of the new League of Nations, but the League had few major achievements, none of which greatly affected Britain or its Empire.

Breakup of the Ottoman Empire

The Sykes–Picot Agreement was a secret 1916 agreement between Great Britain and France. It decided how the lands of the Ottoman Empire would be divided after its defeat. The agreement defined their agreed spheres of influence and control in the Middle East. The agreement gave Britain control of areas roughly including the coastal strip between the Mediterranean Sea and the River Jordan, Jordan, southern Iraq, and a small area with the ports of Haifa and Acre, to allow access to the Mediterranean. France got control of southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. Russia was supposed to get Constantinople, the Turkish Straits, and Armenia. The controlling powers could decide state boundaries within their areas. Further talks were expected to determine international administration after consulting with Russia and other powers, including Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca.

The promises to Russia ended when it left the war. After the Ottoman defeat in 1918, the subsequent partitioning of the Ottoman Empire divided the Arab provinces outside the Arabian peninsula into areas controlled or influenced by Britain and France. Britain ruled Mandatory Iraq from 1920 until 1932, while the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon lasted from 1923 to 1946.

The British took control of Palestine in 1920 and ruled it as Mandatory Palestine from 1923 until 1948. However, the British, in the Balfour Declaration of 1917, promised a Jewish zone with an unclear status, which was unacceptable to Arab leaders.

Lloyd George's Decline

A series of foreign policy crises gave Prime Minister David Lloyd George his last chance to lead nationally and internationally. Everything went wrong. The League of Nations, off to a slow start, was a huge disappointment from utopian dreams. The Treaty of Versailles had set up temporary organizations, made of delegations from key powers, to ensure the Treaty was successfully applied. The system worked very poorly. The assembly of ambassadors was repeatedly overruled and became unimportant. Most commissions were deeply divided and unable to make decisions or convince the involved parties to carry them out. The most important commission was on Reparations, and France took full control of it. The new French prime minister Raymond Poincaré was strongly anti-German, relentless in his demands for huge reparations, and repeatedly challenged by Germany. France finally invaded parts of Germany, and Berlin responded by causing runaway inflation that seriously damaged the German economy and also harmed the French economy. The United States, after refusing to join the League in 1920, almost completely separated itself from the League.

In 1921, the Anglo-Soviet Trade Agreement successfully opened trade relations with Communist Russia. Lloyd George was unable to negotiate full diplomatic relations, as the Russians rejected all repayment of debts from the Tsarist era. Conservatives in Britain grew very wary of the communist threat to European stability. In 1922, Lloyd George set out to make himself the master of peace in the world, especially through a world conference in Genoa that he expected would be as visible as Paris in 1919 and restore his reputation. Everything went wrong. Poincaré and the French demanded a military alliance that was far beyond what the British would accept. Germany and Russia made their own sweeping agreement at Rapallo, which ruined the Genoa conference. Finally, Lloyd George decided to support Greece in a war against Turkey in the Chanak Crisis. It was another disaster, as all but two of the Dominions refused support, and the British military was hesitant. The Conservatives rejected a war, with Bonar Law telling the nation, "We cannot act alone as the policeman of the world." Greece lost its war, and Lloyd George lost control of his coalition. He never again held a major office. Internationally and especially at home, Lloyd George, the hero of the world war, had suddenly become a failed leader.

Disarmament was high on the public agenda, and Britain supported the United States' leadership in the Washington Naval Conference of 1921 in working toward naval disarmament of the major powers. Britain played a leading role in the 1927 Geneva Naval Conference and the 1930 London Conference that led to the London Naval Treaty. However, the refusal of Japan, Germany, Italy, and Russia to go along led to the meaningless Second London Naval Treaty of 1936. Disarmament had collapsed, and the issue became rearming for a war against Germany.

Britain was less successful in negotiating with the United States regarding the large wartime loans. The U.S. insisted on repayment of the full £978 million. It was agreed to in 1923 at an interest rate of 3% to 3.5% over 62 years. Under Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, Britain took the lead in getting France to accept the American solution to reparations through the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan. Under these plans, Germany paid its reparations using money borrowed from New York banks. The Great Depression starting in 1929 put enormous pressure on the British economy. Britain moved toward imperial preference, which meant low tariffs among the Commonwealth of Nations and higher barriers to trade with outside countries. The flow of money from New York dried up, and the system of reparations and debt payments collapsed in 1931. The debts were renegotiated in the 1950s.

Seeking Stability in Europe

Britain sought peace with Germany through the Locarno Treaties of 1925. A main goal was to restore Germany to a peaceful, prosperous state.

The success at Locarno in handling the German question pushed Foreign Secretary Austen Chamberlain, working with France and Italy, to find a master solution to the diplomatic problems of Eastern Europe and the Balkans. It proved impossible to overcome mutual dislikes because Chamberlain's plan was flawed by his misunderstandings and wrong judgments.

Britain thought disarmament was the key to peace. France, with its deep fear of German militarism, strongly opposed the idea. In the early 1930s, most Britons saw France, not Germany, as the main threat to peace and harmony in Europe. France did not suffer as severe an economic downturn and was the strongest military power, but it still refused British offers for disarmament.

The Dominions (Canada, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand) gained virtual independence in foreign policy in 1931, though each depended heavily on British naval protection. After 1931, trade policy favored the Commonwealth with tariffs against the U.S. and others.

Foreign Policy and Home Politics

The Labour Party came to power in 1924 under Ramsay MacDonald, who served as party leader, prime minister, and foreign secretary. The party had a unique foreign policy based on pacifism. It believed that peace was impossible because of capitalism, secret diplomacy, and the trade in weapons. That is, it focused on material factors that ignored the psychological memories of the Great War and the highly emotional tensions regarding nationalism and country borders. Nevertheless, MacDonald overcame these ideological limits and proved very successful in managing foreign affairs. In 1929, the Americans gave him a ticker-tape parade in New York City.

The Zinoviev letter appeared during the 1924 general election. It claimed to be a directive from the Communist International in Moscow to the Communist Party of Great Britain. It said that resuming diplomatic relations (by a Labour government) would speed up the radicalization of the British working class. It was a forgery, but it helped defeat Labour as the Conservatives won by a landslide. A.J.P. Taylor argues that the most important impact was on the psychology of Labour members, who for years blamed their defeat on foul play. This led them to misunderstand the political forces at work and delayed needed reforms in the Labour Party. MacDonald returned to power in 1929. There was little pacifism left. He strongly supported the League of Nations, but he also felt that unity within the British Empire and a strong, independent British defense program would be the best policy.

The 1930s

The challenge came from dictators, first Benito Mussolini of Fascist Italy from 1923, then from 1933 Adolf Hitler of a much more powerful Nazi Germany. Britain and France led the policy of non-interference in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). The League of Nations disappointed its supporters; it was unable to solve any of the threats posed by the dictators. British policy was to "appease" them (give in to their demands) in the hopes they would be satisfied. League-authorized sanctions against Italy for its invasion of Ethiopia had support in Britain but failed and were dropped in 1936.

Germany was the difficult case. By 1930, British leaders and thinkers largely agreed that all major powers shared the blame for the war in 1914, not Germany alone as the Treaty of Versailles stated. Therefore, they believed the harshness of the Treaty of Versailles was unfair. This view, adopted by politicians and the public, was largely responsible for supporting appeasement policies until 1938. That is, German rejections of treaty provisions seemed justified.

Leading up to World War II

By late 1938, it was clear that war was coming, and that Germany had the world's most powerful military. British military leaders warned that Germany would win a war, and Britain needed another year or two to catch up in terms of aviation and air defense. The final act of appeasement came when Britain and France gave up the Sudetenland border regions of Czechoslovakia to Hitler's demands at the Munich Agreement of 1938. Hitler was not satisfied and, in March 1939, seized all of Czechoslovakia and threatened Poland. At last, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain stopped appeasement and stood firm in promising to defend Poland. Hitler, however, made a deal with Joseph Stalin to divide Eastern Europe. When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Britain and France declared war; the British Commonwealth followed London's lead.

Second World War (1939-1945)

Since 1945