Historiography of the British Empire facts for kids

The history of the British Empire looks at how experts have studied and understood the British Empire over time. It focuses on the ideas of historians, not on specific events or places. Scholars have long explored why the Empire formed, how it interacted with other empires like the French, and what kinds of people supported or opposed it. They also study how the Empire ended, especially in places like the United States (which became independent in 1776), India (which gained freedom in 1947), and African countries (which became independent in the 1960s). Historian John Darwin (2013) says the Empire had four main goals: settling new lands, making people more "civilized," converting them to Christianity, and trading.

Over the last century, historians have studied the Empire from many different angles. More recently, they have looked at new topics like social and cultural history. They pay special attention to how the Empire affected local people and how those people responded. Newer studies also focus on language, religion, gender, and identity. There are debates about how Great Britain (the "metropole") influenced its colonies and how the colonies influenced Britain. Some historians focus on the strong connections between British people who moved to different parts of the Empire. Others, called "new imperial historians," look at how the Empire changed everyday life and ideas back in Britain. By the 1990s, few historians still saw the Empire as completely good. They found that local people often adapted to British rule in many ways.

Contents

- How Historians See the British Empire

- Understanding the Idea of Empire

- First and Second British Empires

- Ideas About Imperialism

- Good Intentions, Human Rights, and Slavery

- Regions of the Empire

- Nationalism and Opposition to the Empire

- Ideas of Anti-Imperialism

- World War II and the Empire

- Decline and Decolonization

- New Imperial History

- Impact on Britain and British Memory

- See also

How Historians See the British Empire

Historians generally agree that the British Empire was not planned from the start. It wasn't a single legal country like the Roman Empire. There was no "imperial constitution" or one set of laws for everyone. So, when it began, when it ended, and how it changed are matters of opinion, not official rules. A big change happened between 1763 and 1793. Britain shifted its focus from western lands (like America) to eastern lands after the U.S. became independent. The way London managed the colonies also changed, and slavery was slowly ended.

The Empire's Beginnings

The start of the Empire is also debated. The Tudor conquest of Ireland began in the 1530s, and the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland in the 1650s finished Britain's control over Ireland. The first major history book about the Empire was The Expansion of England (1883) by Sir John Seeley. It was very popular and admired by those who supported the Empire. Seeley argued that British rule was good for India. He also warned that India needed protection, which increased Britain's responsibilities. He famously wrote that Britain seemed to have "conquered half the world in a fit of absence of mind." This book helped many British people see the colonies as an extension of Britain itself. However, later historians like A. P. Newton (1940) felt Seeley's book gave a false idea that the Empire was built mostly through war.

Historians often point out that in the First British Empire (before the 1780s), there wasn't one big plan. Instead, different groups of English business people or religious groups started colonies. The Royal Navy protected them, but the government didn't fund or plan them. After the American War, British leaders focused on trade and how Britain related to its colonies.

The Second British Empire

By 1815, historians see four main parts to the Second British Empire. First, there were self-governing colonies in the Caribbean, Canada, and Australia. Second, India was unique. Its huge size meant Britain had to control the sea routes to it, giving Britain naval power from the Persian Gulf to the South China Sea. Third, there were smaller territories like trading ports such as Hong Kong and Singapore, and some ports in Africa. Fourth, there was the "informal empire." This meant Britain had financial control through investments, like in Latin America, and a complex situation in Egypt. Historian John Darwin says the British Empire was special because its builders were very adaptable. They tried to avoid fighting and instead worked with local leaders and business people. These local leaders gained power and protection from Britain.

Historians say Britain built an informal economic empire in Latin America after Spanish and Portuguese colonies became independent around 1820. By the 1840s, Britain used a successful policy of free trade. This gave it control over much of the world's trade. After losing its first Empire in America, Britain focused on Asia, Africa, and the Pacific. After defeating France in 1815, Britain had a century of strong power and expanded its Empire globally. In the 20th century, white settler colonies gained more self-rule.

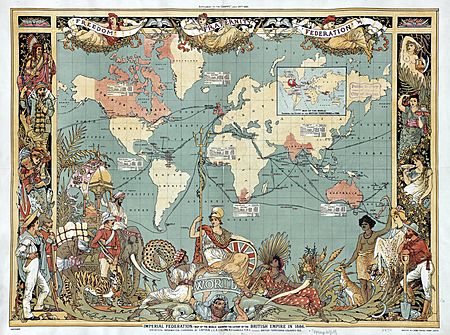

New Growth and Key Figures

The Empire grew again in the late 1800s, with the "Scramble for Africa" and new lands in Asia and the Middle East. Leaders like Joseph Chamberlain and Lord Rosebery pushed for British imperialism. Figures like Cecil Rhodes in Africa, Lord Cromer, Lord Curzon, General Kitchner, Lord Milner, and writer Rudyard Kipling were also important. They were all influenced by Seeley's book. The British Empire became the largest in history, in both land and population. Its power was unmatched in 1900. In 1876, Queen Victoria became "Empress of India."

Before the 1960s, British historians focused on the Empire's diplomacy, military, and administration. They often saw it as a good thing. Younger historians then looked at social, economic, and cultural topics. They took a much more critical view. An example of the older style was the Cambridge History of India (1922-1937). Critics said its research methods were old-fashioned.

Understanding the Idea of Empire

David Armitage studied how the idea of a British Empire grew from the 1500s to the 1700s. He argues that this idea helped form a British state from England, Scotland, and Ireland. It also linked Britain to its colonies across the Atlantic. Before 1700, different English and Scottish ideas about empire made it hard for a single idea to form. But later, thinkers like Nicholas Barbon and Charles Davenant stressed the importance of trade, especially trade closed to outsiders (called mercantilism). They believed that "trade depended on liberty, and that liberty could therefore be the foundation of empire." To create a single "British" empire, Parliament began to control the Irish economy and passed the Acts of Union 1707.

Economic Policy: Mercantilism

Mercantilism was the main economic policy for the British Empire before the 1840s. It was a system where governments controlled their country's economy to gain power over other nations. It was like the economic side of political absolutism. This policy aimed to gather money (like gold and silver) by selling more goods than were bought. Mercantilism was common in Europe from the 1500s to the late 1700s. It often led to wars and encouraged colonies.

Mercantilist policies included:

- Building colonies overseas.

- Forbidding colonies to trade with other countries.

- Having special "staple ports" where all trade had to go.

- Banning the export of gold and silver.

- Only allowing trade on national ships.

- Giving money to industries that exported goods.

- Limiting wages.

- Using as many local resources as possible.

- Limiting what people could buy at home.

For its colonies, British mercantilism meant the government and merchants worked together. Their goal was to increase Britain's power and wealth, keeping other empires out. The government used trade barriers, rules, and money for local industries to boost exports and reduce imports. The Royal Navy protected the colonies and fought smuggling. Smuggling became popular in America in the 1700s to get around trade rules with France, Spain, or the Netherlands. The aim was to have more gold and silver flow into London. The government took its share through taxes, and the rest went to British merchants. Colonies were forced to buy British goods and could only produce raw materials for Britain. This led to smuggling and tension with colonial business people. Mercantilist policies were a big reason for the American Revolution.

Mercantilism taught that trade was a "zero-sum game." This meant one country's gain was another's loss. Even with its flaws, Britain became the world's top trader and a global power under mercantilist policies before the 1840s. Britain gradually moved away from mercantilism after 1815. Free trade, with no tariffs, became the main idea from the 1840s to the 1930s.

Defending the Empire

John Darwin has looked at how historians explain the big role of the Royal Navy and the smaller role of the British Army in the Empire's history. For the 20th century, he talks about a "pseudo-empire" of oil producers in the Middle East. Protecting the Suez Canal was very important from the 1880s to 1956, and this expanded to oil regions. Darwin says defense strategy had to balance home politics with keeping the global Empire safe.

Darwin argues that the British defense system, especially the Royal Navy, mainly protected the overseas empire. The army, often with local forces, stopped internal revolts. The only major loss was the American War of Independence (1775–83). Armitage believes the British thought their Protestantism, sea trade, and control of the seas protected their freedom. This freedom was shown in Parliament, law, property, and rights, which were spread across the British Atlantic world. This freedom, they believed, allowed the British to combine liberty and empire.

Lizzie Collingham (2017) highlights how expanding food supplies helped build, fund, and defend the trade side of empire-building.

Thirteen American Colonies and Revolution

The first British Empire focused on the 13 American Colonies. Many settlers from Britain moved there. From the 1900s to the 1930s, the "Imperial School" of historians saw the Empire positively. They stressed its successful economic connections.

Historian Herbert L. Osgood (1855–1918) brought new ideas to studying colonial relations. He was the first American historian to see how complex the Empire's structures were. He also noted the differences between theory and practice that caused problems. He believed American factors, not imperial ones, shaped the colonies' development.

Much of the history focuses on why Americans revolted in the 1770s and became independent. The "Patriots" (a name they adopted proudly) emphasized their rights as Englishmen, especially "No taxation without representation." Since the 1960s, historians have shown that the Patriot argument was possible because Americans felt a sense of shared identity. This identity came from a Republican idea that people should consent to be governed and oppose control by aristocrats. In Britain, republicanism was a small idea. In the 13 colonies, there were almost no aristocrats. Instead, politics was based on free elections open to most white men.

Historians today use three main ways to understand the Revolution:

- Atlantic history: This view puts the American story in a wider context, including revolutions in France and Haiti. It connects the history of the American Revolution with that of the British Empire.

- New social history: This looks at how communities were structured to find divisions that grew into colonial conflicts.

- Ideological approach: This focuses on republicanism in the United States. Republicanism meant no royalty, aristocracy, or national church. But it kept British common law, which American lawyers used. Historians have studied how American lawyers changed British common law to fit republican ideas.

First and Second British Empires

Historians in the early 1900s started talking about a "First" and "Second" British Empire. Timothy H. Parsons (2014) argued there were "several British empires that ended at different times." He focused on the Second Empire.

The First Empire began in the 1600s. It was based on many settlers moving to American colonies and sugar plantations in the West Indies. It ended when Britain lost the American War for Independence. The Second Empire had already started. It began as a network of trading ports and naval bases. But it grew inland when the East India Company took control of most of India. India became the most important part of the Second Empire, along with later colonies in Africa. Some new settler colonies also grew in Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Historians agree that the idea of a "First British Empire" has remained strong since 1900.

Historians debate if 1783 was a clear break between the First and Second Empires. Some say there was an overlap, or even a "black hole" between them. Denis Judd says the "black hole" idea is wrong and that there was continuity. He writes that in 1783, "there was still a substantial Empire left." The exact dates for the two empires vary, but 1783 is a common dividing line. Books like The Fall of the First British Empire (1982) by Robert W. Tucker and David Hendrickson focus on the American victory. In contrast, Brendan Simms' Three Victories and a Defeat (2007) explains Britain's loss by saying it upset other major European powers.

Ideas About Imperialism

Theories about imperialism usually focus on the Second British Empire. The word "Imperialism" was first used in English in the 1870s by William Gladstone. He used it to criticize Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli's imperial policies, calling them aggressive. Later, supporters like Joseph Chamberlain adopted the term. For some, imperialism meant idealism and helping others. For others, it was about political self-interest and greed.

John A. Hobson, a British Liberal, wrote an important book called Imperialism: A Study (1902). He argued that funding overseas empires took money away from Britain. He believed money was invested abroad because workers there were paid less, leading to higher profits. So, while wages in Britain stayed higher, they didn't grow as fast as they could have. He concluded that sending money abroad limited wage growth and living standards at home. By the 1970s, historians like David K. Fieldhouse and Oren Hale said Hobson's ideas were mostly disproven by the British experience. However, European Socialists, especially Vladimir Lenin, used Hobson's ideas. Lenin's Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916) became a standard textbook for Marxists until the fall of communism. Lenin saw imperialism as capitalism's final stage, where big companies needed to expand to new markets, leading to colonial growth and world wars.

The meaning of "imperialism" has changed over time. It now includes moral, economic, systemic, cultural, and time-related aspects. These changes show a growing discomfort with the idea of Western power.

Historians and thinkers have long debated how capitalism, imperialism, exploitation, social reform, and economic development are linked. Hobson argued that social reforms at home could stop imperialism by fixing its economic causes. He thought government taxes could boost spending, create wealth, and lead to a peaceful world. If the government didn't act, he believed wealthy people would cause imperialism.

Hobson was very influential in Liberal circles. Lenin's writings became central for Marxist historians. But they had many critics. D. K. Fieldhouse, for example, said their arguments were weak. Fieldhouse argued that British expansion after 1870 was driven by explorers, missionaries, engineers, and politicians who cared little about financial investments. Hobson's reply was that hidden financiers controlled everyone. Lenin believed capitalism was dying and controlled by monopolies that sought profits from protected markets. Fieldhouse rejects these ideas as guesses.

Free Trade Imperialism

Historians agree that in the 1840s, Britain adopted a free-trade policy. This meant open markets and no tariffs throughout the Empire. The debate is about what free trade actually meant. "The Imperialism of Free Trade" is a famous 1952 article by John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson. They argued that the "New Imperialism" of the 1880s (like the Scramble for Africa) was a continuation of a long-term policy. This policy preferred informal influence over formal control. Their article helped start the Cambridge School of historiography. Gallagher and Robinson created a new way to understand European imperialism. They showed that European leaders didn't think "imperialism" had to mean formal, legal control. Informal influence in independent areas was often more important. According to Wm. Roger Louis, historians had been too focused on formal empires and maps colored red. Most British people, trade, and money went to areas outside the formal Empire. The key idea was to have an empire "informally if possible and formally if necessary." Oron Hale says Gallagher and Robinson found few capitalists or capital in Africa. Decisions to take over lands were usually based on political reasons.

Historian Martin Lynn (late 20th century) thinks Gallagher and Robinson overstated the impact. He says Britain did increase its economic interests, but it didn't fully "regenerate" societies to tie them to British economic interests.

The idea that free-trade empires use informal controls to expand their economic influence has attracted Marxists. This helps them avoid problems with earlier Marxist ideas about capitalism. This approach is often used to study American policies.

Free Trade vs. Tariffs

Historians have started to look at the effects of British free-trade policy, especially how American and German high tariffs impacted it. Canada adopted high tariffs in the late 1800s to protect its new industries from cheaper imports from the U.S. and Britain. In Britain, there was a growing demand to end free trade and impose tariffs to protect its industries from American and German competition. Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914) made "tariff reform" (higher tariffs) a big issue in British politics. By the 1930s, Britain started to shift away from free trade. They moved towards low tariffs within the British Commonwealth and higher tariffs for outside products. Economic historians have debated how these tariff changes affected economic growth.

Gentlemanly Capitalism

Gentlemanly capitalism is a theory by P. J. Cain and A. G. Hopkins (1980s, fully developed in 1993). It suggests that British imperialism was driven by the business interests of London's financial sector and wealthy landowners. This theory shifts focus away from manufacturers and military strategy. It suggests that the Empire's expansion came from London and its financial world.

Good Intentions, Human Rights, and Slavery

Kevin Grant shows that many historians today explore the links between the Empire, international government, and human rights. They focus on British ideas about world order from the late 1800s to the Cold War. British thinkers and leaders felt it was their duty to protect human rights and help local people move away from old traditions and cruel practices (like suttee in India or foot binding in China). The idea of "benevolence" (doing good) grew between 1780 and 1840. Idealists made moral rules that annoyed colonial administrators and merchants who cared more about profit. This also involved fighting corruption in the Empire. A big success was the end of slavery, led by William Wilberforce and other religious reformers. Christian missionary work also expanded. Edward Gibbon Wakefield (1796–1852) led efforts to create model colonies like South Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. The 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, meant to protect Maori rights, is now key to New Zealand's biculturalism. Wakefield wanted to promote hard work and a productive economy, not just send criminals to colonies.

Slavery: Promotion and Abolition

Historian Jeremy Black says: "Slavery and the slave trade are the most difficult and contentious aspect of the imperial legacy... it leaves a clear and understandable hostility to empire in the Atlantic world."

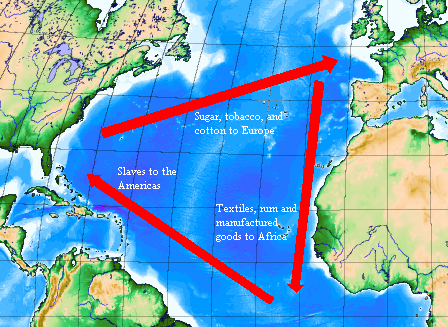

One of the most debated parts of the Empire is its role in first promoting and then ending slavery. In the 1700s, British ships were the largest transporters of slaves across the "Middle Passage" to the Western Hemisphere. Most survivors ended up in the Caribbean, where the Empire had very profitable sugar colonies. Living conditions for slaves were terrible. The British Parliament ended the international slave trade in 1807 and used the Royal Navy to enforce it. In 1833, Britain bought out plantation owners and banned slavery. Before the 1940s, historians said moral reformers like William Wilberforce were mainly responsible.

Later, historian Eric Williams, a Marxist, argued in Capitalism and Slavery (1944) that abolition was more about profit. He said sugar cane farming had worn out the soil, making plantations unprofitable. It was cheaper to sell the slaves to the government than to keep them. Williams also claimed that profits from the slave trade helped fund the Industrial Revolution in Britain.

Since the 1970s, many historians have challenged Williams. Gad Heuman says recent research shows Caribbean colonies were still very profitable during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Seymour Drescher argues that Britain ended the slave trade in 1807 because of public moral outrage, not because slavery was no longer profitable. Critics also say slavery was still profitable in the 1830s due to farming improvements. Richardson (1998) found that slave trade profits were less than 1% of Britain's domestic investment. He also challenged claims that the slave trade caused widespread depopulation in Africa. He noted that Africans controlled the first stage of the trade, capturing people and selling them to Europeans. After 1750, African elites made large profits from slavery, increasing their wealth and power.

Economic historian Stanley Engerman found that even without counting costs, total profits from the slave trade and West Indian plantations were less than 5% of the British economy during the Industrial Revolution.

"Civilizing Mission" and Its Challenges

Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800–1859) was a leading historian. He believed British history was a journey towards more freedom and progress. Macaulay also helped change India's education system. He wanted it to use English so India could progress like Britain. He gave the British Empire a strong moral goal: to "civilize" local people.

Yale professor Karuna Mantena argues that the "civilizing mission" didn't last long. She says reformers lost key debates after events like the 1857 rebellion in India and the brutal handling of the Morant Bay rebellion in Jamaica in 1865. The idea of civilizing continued, but it became an excuse for British misrule and racism. It was no longer believed that local people could truly progress. Instead, they were to be ruled strictly, with democracy delayed.

Historian Peter Cain disagrees with Mantena. He argues that imperialists truly believed British rule would bring "ordered liberty" to their subjects. This would allow Britain to fulfill its moral duty and become great. Much of this debate happened in Britain. Imperialists worked hard to convince the public that the civilizing mission was working. This helped strengthen support for the Empire at home.

Public Health

Mark Harrison says that public health administration in India began when the Crown took over in 1859. Medical experts found that diseases had weakened British troops during the 1857 rebellion. They insisted that preventing disease was better than waiting for outbreaks. Across the Empire, setting up public health systems became a high priority. They used the best practices from Britain, with detailed administrative structures in each colony. The system relied on trained local leaders to improve sanitation, quarantines, vaccinations, hospitals, and treatment centers. For example, local midwives were trained to provide care for mothers and babies. Campaigns with posters, rallies, and films educated the public. A big challenge came from increased travel, which spread diseases like the plague in the 1890s. This made public health programs even more urgent. Michael Worboys says that tropical disease control in the 20th century had three phases: protecting Europeans, improving health for local workers, and finally, fighting major diseases among local people.

Donald McDonald argues that India had the most advanced public health program (besides the self-governing dominions). The Indian Medical Service (IMS) was set up. The British Raj also created the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine in 1921 for advanced study.

Religion: Missionaries

In the 1700s and especially the 1800s, British missionaries saw the Empire as a great place to spread Christianity. Churches across Britain received reports and gave money. All major Christian groups were involved. Much of this energy came from the Evangelical revival. The two largest groups were the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) (1701) and the more evangelical Church Mission Society (1799).

Before the American Revolution, Anglican and Methodist missionaries were active in the 13 Colonies. After the Revolution, a separate American Methodist church became the largest Protestant group in the U.S. A big problem for colonial officials was the Church of England's demand to set up an American bishop, which most Americans strongly opposed. Colonial officials became more neutral on religious matters. After America broke free, British officials decided to strengthen the Church of England in other settler colonies, especially Canada.

Missionary societies funded their own work and were not controlled by the Colonial Office. This sometimes caused tension with colonial officials. Officials worried missionaries might cause trouble or encourage local people to challenge British rule. Generally, officials preferred to work with existing local leaders and religions rather than introduce Christianity, which could divide people. This was especially true in India, where few local elites became Christian. In Africa, however, missionaries made many converts. By the 21st century, there were more Anglicans in Nigeria than in England.

Christianity had a big impact beyond just converts. It offered a model of modern life. European medicine was very important, as were European political ideas like religious freedom, mass education, printing, newspapers, and democracy. Missionaries increasingly added non-religious roles to their spiritual work. They tried to improve education, healthcare, and helped modernize local people to adopt European middle-class values. They built schools and clinics, and sometimes showed better farming methods. Christian missionaries played a public role, especially in promoting sanitation and public health. Many were trained as doctors or took courses in public health and tropical medicine.

Historians have also started to look at the role of women in overseas missions. At first, only men were officially missionaries, but women increasingly took on many roles. Single women often worked as teachers. Wives helped their missionary husbands.

Education

In colonies that became self-governing dominions, education was mostly handled by local officials. The British government took a strong role in India and most later colonies. The goal was to speed up modernization and social development. This included widespread elementary education for all local people, plus high school and university education for selected elites. Students were encouraged to attend university in Britain.

Direct and Indirect Control

Older historical studies often focused on the detailed daily operations of the Imperial government. More recent studies look at who the bureaucrats and governors were, and how their colonial experience affected their lives and families. The cultural approach asks how bureaucrats presented themselves and convinced local people to accept their rule.

Wives of senior officials played a growing role in dealing with local people and supporting charities. When they returned to Britain, they influenced upper-class opinions about colonization. Historian Robert Pearce notes that many colonial wives had a negative reputation. But he describes Violet Bourdillon (1886–1979) as "the perfect Governor's wife." She charmed both British business people and local Nigerians, showing respect and making the British seem like guides and partners in development.

Some British colonies were ruled directly by London. Others were ruled indirectly through local leaders, who were supervised by British advisors. This led to different economic results.

In much of the Empire, large local populations were ruled closely with local leaders. Historians use terms like "subsidiary alliances," "paramountcy," "protectorates," "indirect rule," and "collaboration." Local elites were given leadership positions. They often helped reduce opposition from local independence movements.

Fisher has studied how indirect rule began. The British East India Company, from the mid-1700s, placed its staff as agents in Indian states it didn't directly control. By the 1840s, this became an efficient way to govern indirectly. It involved giving local rulers detailed advice approved by central authorities. After 1870, military officers often took this role. The indirect rule system spread to many colonies in Asia and Africa.

Economic historians have looked at the economic effects of indirect rule in places like India and West Africa. In 1890, Zanzibar became a protectorate (not a colony) of Britain.

Colonel Sir Robert Groves Sandeman (1835–1892) created a new system to bring peace to Balochistan (1877-1947). He paid tribal chiefs who kept control and only used British military force when needed. However, the Government of India generally opposed his methods. Historians still debate how effective his system was in spreading Imperial influence peacefully.

Environment

Environmental history began to grow rapidly after 1970, but it only reached empire studies in the 1990s. Gregory Barton argues that the idea of environmentalism came from forestry studies. He highlights the British Empire's role in this research. He says the imperial forestry movement in India around 1900 included government protected areas, new fire protection methods, and managing forests for income. This helped ease the conflict between those who wanted to preserve nature and business people, leading to modern environmentalism.

Recently, many scholars have looked at the Empire's environmental impact. Beinart and Hughes say that finding and using new plants for business or science was important in the 1700s and 1800s. Using rivers efficiently with dams and irrigation was an expensive but important way to increase farm production. To use natural resources better, the British moved plants, animals, and goods around the world. This sometimes caused ecological problems and big environmental changes. Imperialism also led to more modern views of nature and supported botany and agricultural research. Scholars use the British Empire to study "eco-cultural networks." These are connected social and environmental processes.

Regions of the Empire

Between 1696 and 1782, the Board of Trade and various secretaries of state managed colonial affairs, especially in British America.

From 1783 to 1801, the British Empire, including British North America, was run by the Home Office. From 1801 to 1854, it was managed by the War Office (which became the War and Colonial Office). From 1824, the Empire was divided into four departments: NORTH AMERICA, the WEST INDIES, MEDITERRANEAN AND AFRICA, and EASTERN COLONIES. North America included:

The Colonial Office and War Office were separated in 1854. The War Office then divided the military control of British colonies into nine districts. North America And North Atlantic included:

- New Westminster (British Columbia)

- Newfoundland

- Quebec

- Halifax

- Kingston, Canada West

- Bermuda

India was managed separately by the East India Company until 1858. Then it was transferred to the India Office, which closed in 1947 when India became independent. British British protectorates were not British territory, so they were managed separately by the Foreign Office.

Studies of the Whole Empire

In 1914, The Oxford Survey Of The British Empire (six volumes) covered the geography and society of the entire Empire, including Britain.

Since the 1950s, historians have focused on specific countries or regions. By the 1930s, the Empire was so vast that it was hard for historians to study it all. The American Lawrence H. Gipson (1880–1971) won a Pulitzer Prize for his huge 15-volume work, "The British Empire Before the American Revolution" (1936–70). Around the same time, Sir Keith Hancock wrote a Survey of Commonwealth Affairs (1937–42). This greatly expanded the study beyond politics to economic and social history.

Recently, many scholars have written one-volume surveys, including T. O. Lloyd, Denis Judd, Lawrence James, Niall Ferguson, Brendan Simms, Piers Brendon, and Phillip J. Smith. There were also popular histories by Winston Churchill and Arthur Bryant. Many writers were inspired by Edward Gibbon's famous The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Brendon notes that Gibbon's work became a guide for Britons trying to understand their own Empire. W. David McIntyre's The commonwealth of nations (1977) covers political and constitutional relations from London's view.

Ireland

Ireland, often seen as the first British Empire acquisition, has a huge amount of popular and academic writing. Marshall says historians still debate if Ireland should be considered part of the British Empire. Recent work focuses on the ongoing imperial aspects of Irish history, postcolonial ideas, Atlantic history, and how migration shaped the Irish people across the Empire and North America.

Australia

Until the late 1900s, Australian historians used an Imperial framework. They argued that Australia grew from British people, institutions, and culture. They saw the first governors as "tiny sovereigns." Historians traced the path to self-government, with local parliaments and ministers, then Federation in 1901, and finally full independence. This was a story of successful growth into a modern nation. This idea has largely been dropped by recent scholars. Stuart Macintyre's history of Australia shows how historians now focus on the negative and tragic parts.

The first major history was William Charles Wentworth's Statistical, Historical, and Political Description of the Colony of New South Wales (1819). Wentworth showed the terrible effects of the penal colony system. Many historians followed him. Manning Clark's six-volume History of Australia (1962–87) told a story of "epic tragedy."

History Wars

Since the 1980s, some even describe a "history war" in Australia among scholars and politicians. Debates often involve recorded history versus oral stories about how Aboriginal people were treated. They also debate if Australia has been more "British" or "multicultural" historically, and how it should be today. This debate has entered national politics, often linked to whether Australia should become a republic. Some schools and universities have reduced the amount of Australian history in their lessons.

Debates on Australia's Founding

Historians use the founding of Australia to mark the start of the Second British Empire. London planned it as a replacement for the lost American colonies. The American Loyalist James Matra (1783) suggested a colony in New South Wales for American Loyalists, Chinese, and South Sea Islanders (not convicts). Matra thought the land was good for sugar, cotton, and tobacco. New Zealand timber and flax could be valuable. It could be a base for Pacific trade and a home for displaced American Loyalists. At Lord Sydney's suggestion, Matra added convicts as settlers. The government adopted Matra's basic plan in 1784 and funded the convict settlement.

Michael Roe argues that Australia's founding supports Vincent T. Harlow's theory (1964). Harlow said a goal of the second British Empire was to open new trade in the Far East and Pacific. However, London stressed Australia's purpose as a penal colony. The East India Company also opposed potential trade rivals. Still, Roe says Australia's founders were very interested in whaling, sealing, sheep farming, mining, and other trade opportunities. In the long run, he says, trade was the main reason for colonization.

Canada

Canadian historian Carl Berger argues that many English Canadians supported imperialism. They saw it as a way to boost Canada's power in the world. Berger identified Canadian imperialism as a unique idea, different from anti-imperial Canadian nationalism or pro-American continentalism.

For French Canadians, the main debate among historians is about the British conquest in 1763. One group says it was a disaster that stopped the normal growth of a middle-class society for over a century. They say it left Quebec stuck in old traditions controlled by priests and landlords. The other, more hopeful group says it was generally good politically and economically. For example, it helped Quebec avoid the French Revolution. It also connected Quebec's economy to the larger, faster-growing British economy, instead of the slow French one. The hopeful group blames Quebec's economic slowness on deep-seated conservatism and a dislike for business.

India

In recent decades, there have been four main ways historians study India: Cambridge, Nationalist, Marxist, and subaltern. The old "Orientalist" view, which saw India as mysterious and spiritual, is no longer used in serious studies.

The "Cambridge School" (led by Anil Seal and others) focuses less on ideas. However, this school is criticized for being too Western-focused.

The Nationalist school focuses on the Indian National Congress, Gandhi, Nehru, and high-level politics. It highlights the Mutiny of 1857 as a war of liberation and Gandhi's 'Quit India' movement (1942) as key events. This school is criticized for focusing too much on elites.

Marxists focus on economic development, land ownership, and class conflict in India before British rule. They also study how industries declined during the colonial period. Marxists saw Gandhi's movement as a way for the wealthy elite to control popular, revolutionary forces. Marxists are also accused of being too influenced by their own ideas.

The "subaltern school" (started in the 1980s by Ranajit Guha and Gyan Prakash) shifts attention away from elites to "history from below." They look at peasants using folklore, poetry, riddles, proverbs, songs, oral history, and methods from anthropology. It focuses on the colonial era before 1947. It often emphasizes caste and downplays class, which annoys the Marxist school.

More recently, Hindu nationalists have created a version of history to support their demands for "Hindutva" ("Hinduness") in Indian society. This idea is still developing. In 2012, Diana L. Eck argued that the idea of India existed much earlier than the British or Mughals. It was not just a group of regional identities, and it wasn't based on ethnicity or race.

Debate continues about the economic impact of British imperialism on India. Edmund Burke, a British politician, attacked the East India Company in the 1780s. He claimed that officials like Warren Hastings had ruined India's economy and society. Indian historian Rajat Kanta Ray (1998) continues this argument. He says the new economy brought by the British in the 1700s was a form of "plunder" and a disaster for India's traditional economy. Ray accuses the British of taking food and money, and imposing high taxes that helped cause the terrible famine of 1770, which killed a third of Bengal's people.

British historian P. J. Marshall disagrees with the Indian nationalist view of the British as invaders who impoverished India. He argues that the British were not in full control. Instead, they were players in an Indian story, and their rise to power depended on good cooperation with Indian elites. Marshall admits that many historians still reject his view. Marshall argues that recent studies have changed the idea that the good Mughal rule led to poverty and chaos. Marshall says the British takeover didn't create a sharp break with the past. The British largely let regional Mughal rulers stay in control and kept the economy generally good for the rest of the 1700s. Marshall notes the British worked with Indian bankers and collected taxes using old Mughal rates. Professor Ray agrees that the East India Company inherited a heavy tax system that took one-third of what Indian farmers produced.

In the 1900s, historians generally agreed that British rule in India was secure from 1800 to 1940. But this has been challenged. Mark Condos and Jon Wilson argue that British rule in India was always insecure. They say officials' constant worry led to a chaotic administration with little social connection or clear ideas. The British Raj was not a confident state that could do what it wanted. Instead, it was a worried state that could only act in abstract, small, or short-term ways. Meanwhile, Durba Ghosh offers a different view.

Tropical Africa

The first historical studies of Africa appeared in the 1890s. They followed four main paths:

- Territorial narratives: Written by soldiers or civil servants, focusing on what they saw.

- Apologia: Essays justifying British policies.

- Popularizers: Books for a large audience.

- Compendia: Works combining academic and official information.

Professional studies began around 1900, focusing on business operations using government documents. The economic approach was popular in the 1930s, describing changes over the past 50 years. Reginald Coupland, an Oxford professor, studied the Exploitation of East Africa, 1856–1890 (1939). The American historian William L. Langer wrote The Diplomacy of Imperialism: 1890–1902 (1935), which is still widely used. World War II paused scholarship in the 1940s.

By the 1950s, many African students in British universities created a demand for new studies. They also started doing the research themselves. Oxford University became a main center for African studies. The focus slowly shifted from British government policy or international business to the activities of local people, especially nationalistic movements and the growing demand for independence. A major change came from Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher, especially their studies on how free trade affected Africa.

South Africa

The history of South Africa has been one of the most debated areas of the British Empire. It involves three very different views: British, Boer (Dutch settlers), and black African historians. Early British historians stressed the benefits of British civilization. Afrikaner history began in the 1870s with praise for the trekkers and anger at the British. After years of conflict, the British took control of South Africa. Historians then tried to bring the two sides together with a shared history. George McCall Theal (1837-1919) made a big effort, writing many books as a teacher and official historian. In the 1920s, historians using missionary sources began to present the views of Coloured and African people. Eric A. Walker (1886–1976) brought modern research standards. He trained a generation of students at Cambridge. Afrikaner history increasingly defended apartheid.

Liberation History

The main approach in recent decades emphasizes the roots of the liberation movement. Baines argues that the Soweto uprising of 1976 inspired a new generation of historians to write history "from below." They often used a Marxist perspective.

By the 1990s, historians were comparing race relations in South Africa and the United States from the late 1800s to the late 1900s. James Campbell argues that black American Methodist missionaries in South Africa used the same standards of promoting civilization as the British.

Nationalism and Opposition to the Empire

Opposition to imperialism and demands for self-rule grew across the Empire. In all but one case, the British stopped revolts. However, in the 1770s, led by Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson, the 13 American colonies revolted in the American Revolutionary War. With military and financial help from France, the 13 colonies became the first British colonies to gain independence in the name of American nationalism.

There is much written about the Indian Rebellion of 1857. This was a very large revolt in India, involving many native troops mutinying. The British Army put it down after much bloodshed.

Indians organized under Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru and finally gained independence in 1947. They wanted one India, but Muslims, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, created their own nation, Pakistan. This process is still debated by scholars. Independence came with religious violence, mainly between Hindus and Muslims in border areas. Millions died, and millions more were displaced. These memories and grievances still affect tensions in the region.

Historians of the Empire have recently paid close attention to 20th-century voices in many colonies who demanded independence. African colonies mostly became independent peacefully. Kenya saw severe violence. Often, independence leaders had studied in England in the 1920s and 1930s. For example, Kwame Nkrumah led Ghana to become Britain's second African colony to gain independence in 1957 (Sudan was first in 1956). Others quickly followed.

Ideas of Anti-Imperialism

On an intellectual level, anti-imperialism strongly appealed to Marxists and liberals worldwide. Both groups were much influenced by British writer John A. Hobson in his Imperialism: A Study (1902). Historians Peter Duignan and Lewis H. Gann argue that Hobson had a huge impact in the early 1900s. He caused widespread distrust of imperialism:

- Hobson's ideas were not entirely new; however his dislike of rich people and monopolies, his hatred of secret deals and public boasting, combined all existing criticisms of imperialism into one clear system....His ideas influenced German nationalists who opposed the British Empire, as well as French people who disliked Britain, and Marxists. They shaped the thoughts of American liberals and isolationist critics of colonialism. In the future, they would contribute to American distrust of Western Europe and the British Empire. Hobson helped make the British dislike colonial rule; he gave local nationalists in Asia and Africa reasons to resist European rule.

World War II and the Empire

British historians of World War II have not always stressed the important role the Empire played. This includes money, manpower, and imports of food and raw materials. The strong combination meant Britain did not fight Germany alone. It led a great, though fading, empire. As Ashley Jackson argued, "The story of the British Empire's war, therefore, is one of Imperial success in contributing toward Allied victory on the one hand, and egregious Imperial failure on the other, as Britain struggled to protect people and defeat them, and failed to win the loyalty of colonial subjects." The Empire provided 2.5 million soldiers from India, over 1 million from Canada, almost 1 million from Australia, 410,000 from South Africa, and 215,000 from New Zealand. Also, colonies mobilized over 500,000 uniformed personnel, mainly in Africa. For funding, Britain borrowed £2.7 billion from the Empire's Sterling Area, which was eventually paid back. Canada gave C$3 billion in gifts and easy loans.

In terms of fighting the enemy, there was a lot of action in South Asia and Southeast Asia, as Ashley Jackson noted:

- Terror, mass migration, shortages, inflation, blackouts, air raids, massacres, famine, forced labour, urbanization, environmental damage, occupation [by the enemy], resistance, Collaboration – all of these dramatic and often horrific phenomena shaped the war experience of Britain's imperial subjects.

Decline and Decolonization

Historians still debate when the Empire was at its strongest. Some point to the worries of the 1880s and 1890s, especially the rise of industry in the United States and Germany. The Second Boer War in South Africa (1899-1902) angered many Liberals in England. This took away much moral support for imperialism. Most historians agree that by 1918, after World War I, a long-term decline was unavoidable. The self-governing dominions had largely become independent and started their own foreign and military policies. Worldwide investments had been sold to pay for the war, and the British economy was struggling after 1918. A new spirit of nationalism appeared in many colonies, most clearly in India. Most historians agree that after World War II, Britain lost its superpower status and was almost bankrupt. With the Suez fiasco of 1956, its deep weaknesses were clear to everyone, and quick decolonization was certain.

The timeline and main features of the British Empire's decolonization have been studied in detail. Most attention has been given to India in 1947, with less focus on other colonies in Asia and Africa. Of course, most scholarly attention is on the newly independent nations. From the Empire's perspective, historians disagree on two points:

- Could London have handled decolonization better in India in 1947, or was what happened already set in motion in the previous century?

- How much did decolonization affect British society and economy at home?

Bailkin says one view is that the domestic impact was minor, and most Britons paid little attention. She notes that political historians often reach this conclusion. John Darwin has studied the political debates.

On the other hand, most social historians disagree. They say that British values and beliefs about the overseas empire shaped policy. The decolonization process was emotionally difficult for many people in Britain, especially migrants and those with family who worked in overseas civil service, business, or missionary work. Bailkin says decolonization was often taken personally. It had a big impact on British welfare state policies. She shows how some West Indian migrants were sent back home. Idealists volunteered to help the new nations. Many overseas students came to British universities. Polygamous relationships were made invalid. Meanwhile, she says, the new welfare state was partly shaped by British colonial practices, especially regarding mental health and child care. Social historian Bill Schwarz says that as decolonization moved forward in the 1950s, there was a rise in racial segregation.

Thomas Colley finds that informed Britons today agree that Britain has often been at war over centuries. They also agree that the nation has steadily lost its military power due to economic decline and the loss of its empire.

New Imperial History

The focus of historians has changed over time. Hyam states that by the 21st century, new topics had emerged, including "post-colonial theory, globalisation, sex and gender issues, the cultural imperative, and the linguistic turn."

Native Leadership

Studies of policy-making in London and settler colonies like Canada and Australia are now rare. Newer concerns deal with local people and give much more attention to native leaders like Gandhi. So, books like Sarah E. Stockwell's The British Empire: Themes and Perspectives (2008) have chapters on economics, religion, colonial knowledge, agency, culture, and identity. The new ways of studying imperial history are often called "new imperial history." These approaches have two main features. First, they suggest that the British Empire was a cultural project, not just about politics and economics. So, these historians stress how empire-building shaped the cultures of both colonized people and Britons themselves.

Race and Gender

In particular, they have shown how British imperialism was based on ideas about cultural differences. They also show how British colonialism changed understandings of race and gender in both the colonies and in Britain. Mrinalini Sinha's Colonial Masculinity (1995) showed how ideas about British manliness and the supposed weakness of some Indian men influenced colonial policy and Indian nationalist thought. Antoinette Burton is a key figure. Her Burdens of History (1995) showed how white British feminists in the Victorian period used imperialist ideas. They claimed a role for themselves in "saving" native women, which helped them argue for their own equality in Britain. Historians like Sinha, Burton, and Catherine Hall use this approach to argue that British culture at home was deeply shaped by the Empire in the 1800s.

Connections Binding the Empire

The second feature of the new imperial history is its study of the links that connected different parts of the Empire. At first, scholars looked at the Empire's impact on Britain, especially everyday experiences. More recently, attention has been paid to the material, emotional, and financial links between different regions. Both Burton and Sinha stress how gender and race politics linked Britain and India. Sinha suggested these links were part of an "imperial social formation." This was a set of arguments, ideas, and institutions that connected Britain to its colonies. More recent work by scholars like Alan Lester and Tony Ballantyne has stressed the importance of the networks that made up the Empire. Lester's Imperial Networks (2001) looked at debates and policies that linked Britain and South Africa in the 1800s. Ballantyne's Orientalism and Race created a new model for writing about colonialism. He highlighted the "webs of empire" made of ideas, books, arguments, money, and people. These moved not only between London and the colonies but also directly from colony to colony, like from India to New Zealand. Many historians now focus on these "networks" and "webs." Alison Games has used this model to study early English imperialism.

The Oxford History of the British Empire

The main multi-volume work on the British Empire is the Oxford History of the British Empire (1998–2001). It has five volumes plus a companion series. Douglas Peers says the series shows that "imperial history is clearly experiencing a renaissance."

Max Beloff, reviewing the first two volumes, praised them for being easy to read. He was happy they weren't too anti-imperialist. Saul Dubow noted the uneven quality of chapters in volume III. He also noted how hard such a project was given the state of history writing and the impossibility of keeping a triumphant tone today. Dubow felt some authors played it safe, perhaps awed by the huge task.

Madhavi Kale felt the history took a traditional approach. It placed the English (and to a lesser extent, Scottish, Irish, and Welsh) at the center, rather than the colonized people. Kale summarized her review of volumes III-V by saying it was "a disturbingly revisionist project that seeks to neutralize... the massive political and military brutality and repression" of the empire.

Postmodern and Postcolonial Approaches

A big new development after 1980 was a flood of fresh books and articles from scholars trained outside Britain. Many had studied Africa, South Asia, the Caribbean, and the dominions. This new perspective strengthened the field. More creative approaches, which caused sharp debates, came from literary scholars like Edward Said and Homi K. Bhabha, as well as anthropologists, feminists, and others. Long-time experts suddenly faced new scholarship with ideas like post-structuralism and post-modernism. The colonial empire became "postcolonial." Instead of just coloring the globe red, the Empire's history became part of a new global history. New maps were drawn emphasizing oceans more than land, leading to new views like Atlantic history.

The old agreement among historians was that British rule in India was quite secure from 1858 to World War II. Recently, this idea has been challenged. For example, Mark Condos and Jon Wilson argue that British rule in India was always insecure. They say officials' constant worry led to a chaotic administration with little clear purpose. Instead of a confident state, these historians find a worried one that could only act in abstract, small, or short-term ways. Meanwhile, Durba Ghosh offers a different approach.

Impact on Britain and British Memory

Moving away from political, economic, and diplomatic topics, historians have recently looked at how the Empire affected Britain's ideas and culture. The British promoted the Empire by appealing to ideals of political and legal freedom. Historians have always noted the strange contrast between freedom and control within the Empire, and between modern and traditional ideas. Sir John Seeley, for example, wondered in 1883:

- How can the same nation pursue two lines of policy so radically different without bewilderment, be despotic in Asia and democratic in Australia, be in the East at once the greatest Mussulman Power in the World... and at the same time in the West be the foremost champion of free thought and spiritual religion.

Historian Douglas Peers emphasizes that an idealized knowledge of the Empire spread through popular and elite thought in Britain during the 1800s:

- No history of nineteenth-century Britain can be complete without acknowledging the impact that the empire had in fashioning political culture, informing strategic and diplomatic priorities, shaping social institutions and cultural practices, and determining, at least in part, the rate and direction of economic development. Moreover, British identity was bound up with the empire.

Politicians and historians have explored whether the Empire was too expensive for Britain. Joseph Chamberlain thought so, but he had little success at the Imperial Conference of 1902 asking overseas partners to pay more. Canada and Australia talked about funding a warship, but the Canadian Senate voted it down in 1913. Meanwhile, the Royal Navy changed its war plans to focus on Germany, saving money by defending less against smaller threats in areas like the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Public opinion supported military spending out of pride. But the left in Britain leaned towards peace and disliked the waste of money.

In the Porter–MacKenzie debate, the historical question was how the Imperial experience affected British society and thinking. Porter argued in 2004 that most Britons didn't care much about the Empire. Imperialism was handled by elites. In Britain's diverse society, "imperialism did not have to have impact greatly on British society and culture." John M. MacKenzie argued back that there is much evidence to show an important impact. His view was supported by Catherine Hall, Antoinette Burton, and Jeffrey Richards.

A YouGov survey in 2014 found that 59% of Britons thought the British Empire was "more something to be proud of" and 19% were "ashamed of" it. A third (34%) also said they would like it if Britain still had an empire. Less than half (45%) said they would not.

See also

- British Empire Economic Conference (1932)

- Cambridge School of historiography led by John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson

- Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting

- Historiography of the United Kingdom

- Historiography of the causes of World War I

- Imperial Conference, Covers the meetings of prime ministers in 1887, 1894, 1897, 1902, 1907, 1911, 1921, 1923, 1926, 1930, 1932, in 1937

- Imperial War Cabinet

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- New Imperialism, re 1880–1910

- Pageant of Empire

- Porter–MacKenzie debate what role did colonialism play in shaping British culture

- The Cambridge History of the British Empire

- The Oxford History of the British Empire

- Timeline of imperialism

- Western imperialism in Asia

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |