Economic history of the United Kingdom facts for kids

The economic history of the United Kingdom tells the story of how the British economy has grown and changed over time. This story begins when Wales joined the Kingdom of England in the 1500s. It continues through the creation of the United Kingdom and up to today.

Scotland, England, and Wales had the same king from 1601. But their economies were separate until they joined together in 1707. Ireland was part of the UK economy from 1800 to 1922. After 1922, the Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland) became independent and made its own economic rules.

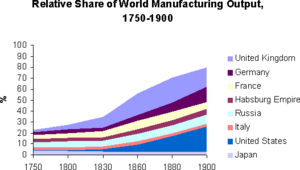

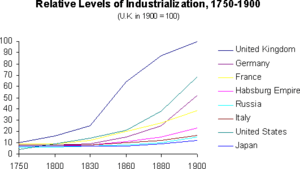

Between 1600 and 1700, Great Britain, especially England, became one of the richest places in Europe. The Industrial Revolution started in the UK in the mid-1700s. This led to huge economic changes. Britain became the top industrial power in the world. It was also a major political power. British inventors created amazing machines like steam engines for factories and trains. They also made textile equipment and tools. Britons were pioneers in building railways. They built many railway systems and made most of the equipment used by other countries. British business people were leaders in global trade and banking. The powerful Royal Navy protected British trade around the world. The City of London became the world's economic center.

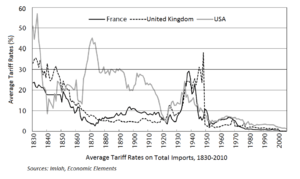

After 1840, Britain stopped using a policy called mercantilism. This policy tried to keep wealth inside the empire. Instead, Britain adopted free trade. This meant fewer taxes or rules on goods coming in or out.

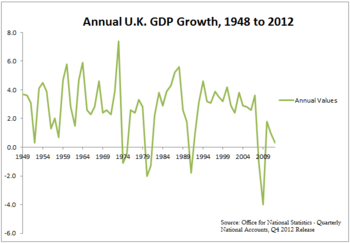

Between 1870 and 1900, the amount of goods and services produced per person in the UK grew by 50%. This meant people's living standards improved a lot. However, other countries like the United States and Germany started to grow their industries even faster. In 1870, Britain was the second richest country per person in the world. By 1914, it was third. By 1950, Britain's output per person was still 30% higher than the average of the first six countries that formed the EEC. But within 20 years, most Western European countries had caught up and passed Britain.

To help the economy grow, British governments decided to join the European Community in 1973. After this, the UK's economy improved a lot. Before the financial crisis of 2007, Britain's income per person was slightly higher than France and Germany. The gap between the UK and the USA also became much smaller.

Contents

How Britain's Economy Grew (1500 to 1700)

Between 1500 and 1700, many big economic changes happened. These changes prepared the way for the Industrial Revolution. After 1600, the UK became the leading economic region in Europe. It took this role from countries around the Mediterranean Sea. A key difference was that Britain had many privately owned businesses. Other countries often had less successful state-owned businesses.

After the Black Death in the mid-1300s, the population started to grow again. Selling wool products helped the economy. England exported these products to Europe.

In the early 1500s, wages were high and there was plenty of land. But this did not last. As the population grew, wages became low again, and land became scarce. This was a time of big change for people living in the countryside. Landlords started to enclose common lands.

There was also a lot of inflation, meaning prices went up. This was partly because of new gold from the Americas and a growing population. Inflation made most families poorer. It also caused social problems, as the gap between rich and poor grew wider.

John Leland wrote detailed descriptions of local economies from 1531 to 1560. He described markets, ports, industries, buildings, and transport. He saw some small towns growing because of new trade and industry, especially cloth making. He also saw other towns shrinking. He suggested that money from business people helped some small towns become rich. Taxes were a problem for economic growth. They were placed on investments, not on what people bought.

What Did Britain Export?

Exports grew a lot during this time, especially within the British Empire. Private companies traded with colonies in the West Indies, North America, and India.

The Company of Merchant Adventurers of London was a group of London's top overseas merchants. They formed a regulated company, like a guild, in the early 1400s. Their main business was exporting cloth, especially undyed woolen cloth. This allowed them to import many foreign goods.

The Wool Industry

Woolen cloth was Britain's main export and the biggest employer after farming. The best time for the Wiltshire woolen industry was during the reign of Henry VIII. Before this, raw wool was exported. But now, England had its own industry, based on its 11 million sheep. London and other towns bought wool from dealers. They sent it to families in the countryside. These families would wash, card, and spin the wool into thread. Then they would weave it into cloth on a loom. Merchants exported these woolens to the Netherlands, Germany, and other places. New skills brought by French Huguenots (Protestants who fled France) helped the industry grow.

What People Ate

What people ate depended on their social class. Rich people ate meat like beef, pork, and venison, and white bread. Poor people ate coarse dark bread, with a little meat sometimes at Christmas. Everyone drank ale because water was often unsafe. Fruits and vegetables were rarely eaten. Rich people used strong spices to cover the smell of old, salted meat. The potato was not part of their diet yet. Rich people enjoyed desserts like pastries, tarts, cakes, and candied fruit.

Both rich and poor people often lacked important nutrients in their diets. Not eating enough fruits and vegetables caused a lack of vitamin C, which could lead to scurvy.

Trade and industry grew in the 1500s. This made England richer and improved the lives of the upper and middle classes. However, the lower classes did not benefit as much. They often did not have enough food. Since England relied on its own farms for food, a series of bad harvests in the 1590s caused widespread hardship.

In the 1600s, the food supply got better. England had no food crises from 1650 to 1725. This was a time when France often suffered from famines.

Poverty in Tudor England

About one-third of the population was poor. Rich people were expected to give money to help the very poor. Tudor law was very strict on able-bodied poor people. These were people who could not find work. Those who left their home parishes to find work were called vagabonds. They could be punished with whipping or being put in the stocks.

Britain's Economy: 1700 to 1900

Besides woolens, making cotton, silk, and linen cloth became important after 1600. Coal and iron production also grew.

Iron Production

In 1709, Abraham Darby I started using coke (a type of fuel made from coal) to produce cast iron. This replaced charcoal. Having cheap iron was one of the reasons for the Industrial Revolution. By the late 1700s, cast iron started to replace wrought iron for some uses because it was cheaper.

The Age of Mercantilism

The British Empire was built during the age of mercantilism. This economic idea focused on trading as much as possible within the empire. It also aimed to weaken rival empires. The British Empire in the 1700s grew from earlier English colonies. These included islands in the Caribbean like Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica. It also included colonies in North America like Virginia and parts of Canada. The sugar plantations in the Caribbean, which relied on slavery, were England's most profitable colonies. The American colonies also used enslaved labor to farm tobacco, indigo, and rice in the south. Britain's empire in America slowly grew through wars and new settlements.

Mercantilism was the main policy Britain used for its colonies. This meant the government and merchants worked together. Their goal was to increase political power and private wealth, keeping other empires out. The government protected its merchants by using trade barriers and rules. It also gave money to local industries to help them export more and import less. The government had to fight smuggling, which became a common way for Americans to get around trade rules in the 1700s. The main goal of mercantilism was to have more exports than imports. This would bring gold and silver into London. The government took its share through taxes. The rest went to merchants in Britain. The government spent a lot of its money on a strong Royal Navy. This navy protected British colonies and trade. It also threatened and sometimes captured colonies from other empires. For example, the British Navy captured New Amsterdam (now New York) in 1664. The colonies were forced to buy British goods. The goal was to make the mother country rich.

The Industrial Revolution

From the 1770s to the 1820s, Britain went through a rapid economic change. It changed from a farming economy to the world's first industrial economy. This is known as the "Industrial Revolution". These changes were huge and lasted a long time across many parts of Britain, especially in the growing cities.

New laws and social changes were key to the Industrial Revolution. While most of Europe had kings with absolute power, the UK had a balance of power after the revolutions of 1640 and 1688. This new system protected property rights and made the country safer for business. This helped a rich middle class grow. Another factor was changes in marriage. People married later, which allowed young people to get more education. This built up more skilled workers. These changes helped the already growing labor and financial markets. All of this prepared the way for the Industrial Revolution, which began in the mid-1700s.

Britain had the right laws and culture for business people to start the Industrial Revolution. In the late 1700s, Britain began to switch from using mostly manual labor and animals to using machines. It started with machines for the textile industry. New ways of making iron and using more refined coal also developed. Trade grew because of new canals, better roads, and railways. Factories drew thousands of people from low-paying farm work to better-paying city jobs.

The invention of steam power, mainly fueled by coal, and more use of water wheels and machines (especially in textile manufacturing) led to huge increases in production. In the early 1800s, new metal machine tools made it easier to build more production machines for other industries. These changes spread across Western Europe and North America in the 1800s. Eventually, they affected most of the world.

A long period of good harvests, starting in the early 1700s, meant people had more money to spend. This led to a higher demand for manufactured goods, especially textiles. John Kay invented the flying shuttle. This machine allowed wider cloth to be woven faster. But it also created a demand for yarn that could not be met. So, the main inventions of the Industrial Revolution were about spinning yarn. James Hargreaves created the Spinning Jenny. This machine could do the work of many spinning wheels. While this invention could be operated by hand, the water frame, invented by Richard Arkwright, could be powered by a water wheel. Arkwright is known for bringing the factory system to Britain. He was the first successful factory owner and industrialist in British history. The water frame was soon replaced by the spinning mule, invented by Samuel Crompton.

Because they used water power, the first mills were built in the countryside near streams or rivers. Worker villages grew up around them, like the New Lanark Mills in Scotland. These spinning mills led to the decline of the domestic system. In this system, spinning was done in rural homes using old, slow equipment.

The steam engine was invented and became a power source that soon replaced waterfalls and animal power. The first useful steam engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen. It was used to pump water out of mines. A much more powerful steam engine was invented by James Watt. It could power machinery. The first steam-driven textile mills appeared in the late 1700s. This made the Industrial Revolution an urban event. It greatly helped industrial towns grow quickly.

The textile trade grew so fast that it soon needed more raw materials than were available. By the early 1800s, imported American cotton had replaced wool in the North West of England. However, wool remained the main textile in Yorkshire. Textiles were the starting point for technological change during this time. Using steam power increased the demand for coal. The demand for machines and rails boosted the iron industry. The need for transportation to move raw materials and finished products led to the growth of canals and, after 1830, railways.

This huge economic growth was not just from demand within Britain. New technology and the factory system allowed for mass production. This made goods so cheap that British manufacturers could sell inexpensive cloth and other items all over the world.

Some people have said that Britain's many overseas colonies or profits from the slave trade helped fund industrial investment. However, it has been pointed out that the slave trade and Caribbean plantations provided less than 5% of Britain's national income during the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution changed the British economy and society very quickly. Before, large industries had to be near forests or rivers for power. But with coal-fueled engines, they could be built in large cities. These new factories were much more efficient at making goods than the old cottage industry. These manufactured goods were sold worldwide. Raw materials and luxury goods were imported into Britain.

The British Empire

During the Industrial Revolution, the empire became less important. Britain's loss in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) meant it lost its largest and most developed colonies. This loss made Britain realize that colonies were not always good for the home economy. The costs of controlling colonies often outweighed the money they brought in. The American Revolution showed that Britain could still trade with the colonies without paying for their defense and government. Capitalism encouraged the British to give their colonies self-government. This started with Canada in 1867 and Australia in 1901.

Napoleonic Wars

Britain's strong economy was key to its success against Napoleon. Britain could use its industrial and financial resources to defeat France. Britain had a population of 16 million, while France had 30 million. France had more soldiers, but Britain paid for many Austrian and Russian soldiers. This meant Britain had about 450,000 allied soldiers by 1813.

Most importantly, Britain's national output remained strong. Textile and iron production grew sharply. Iron production increased because there was a huge demand for cannons and ammunition. Farm prices soared, which was a good time for agriculture. Overall, crop production grew 50% between 1795 and 1815.

Smuggling finished products into Europe weakened France's efforts to harm the British economy. The well-organized business sector made sure the military got what it needed. British cloth was used for British uniforms, allied uniforms, and even French soldiers. Britain used its economic power to expand the Royal Navy. The number of frigates doubled, and large ships increased by 50%. The number of sailors grew from 15,000 to 133,000 in eight years after the war began in 1793. France's navy, meanwhile, shrank by more than half.

The British budget in 1814 reached £66 million. This included £10 million for the Navy, £40 million for the Army, and £10 million for its allies. The national debt grew to £679 million, more than double the country's total output. Hundreds of thousands of investors and taxpayers supported this, despite higher taxes on land and a new income tax. The total cost of the war was £831 million. In contrast, France's financial system was weak. Napoleon's forces had to rely on taking resources from conquered lands.

The wars generally had a good long-term impact on the British economy, except for the working class. The economy was not harmed by sending men to the army and navy. Britain gained more than it lost in terms of destruction and wealth transfer. British control of the oceans helped create a free-trade global economy. This also helped Britain get most of the world's shipping and financial services. The effects were positive for farming and most industries, except construction. The rate of new investments slowed a bit. National income might have grown even faster without the war. The biggest negative impact was a drop in living standards for city workers.

The 19th Century

Free Trade

After 1840, Britain stopped using mercantilism. It committed its economy to free trade, with few barriers or taxes. This was clearest when the Corn Laws were removed in 1846. These laws had put high taxes on imported grain. Ending these laws opened the British market to full competition. Grain prices fell, and food became more plentiful.

From 1815 to 1870, Britain benefited from being the world's first modern, industrialized nation. It called itself 'the workshop of the world'. This meant its finished goods were made so efficiently and cheaply that they could often be sold for less than similar local goods in almost any other market. By 1820, 30% of Britain's exports went to its Empire. This slowly rose to 35% by 1910. Besides coal and iron, most raw materials had to be imported. By 1900, Britain's share of total global imports was 22.8%. By 1922, its share of total exports was 14.9%, and 28.8% of manufactured exports.

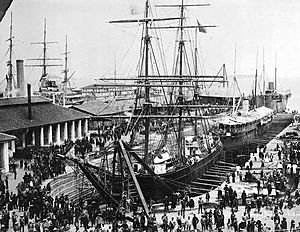

Railways

The British invented the modern railway system and shared it with the world. Railways grew from Britain's system of canals and roads. These had used horses to pull coal for the new steam engines in textile factories. Britain also had the engineers and business people needed to create and pay for a railway system. In 1815, George Stephenson invented the modern steam locomotive. This started a race for bigger, more powerful locomotives. Stephenson's key idea was to connect all parts of a railway system in 1825. He opened the Stockton and Darlington line. This showed that a railway system of a useful length could make money. London invested a lot of money in railway building. This was a huge boom, but it created lasting value. Thomas Brassey brought British railway engineering to the world. In the 1840s, his construction crews employed 75,000 men across Europe. Every nation copied the British model. Brassey expanded throughout the British Empire and Latin America. His companies invented and improved thousands of machines. They also developed civil engineering to build roads, tunnels, and bridges.

The telegraph, invented separately, was vital for railway communication. It allowed slower trains to pull over for express trains. Telegraphs made it possible to use a single track for two-way traffic. They also helped locate where repairs were needed. Britain had a strong financial system in London. This system funded railways in Britain and many other parts of the world, including the United States, until 1914. The boom years were 1836 and 1845–47. During these years, Parliament approved 8,000 miles of railways. The projected cost was £200 million, which was about one year of Britain's total output. Once a railway was approved, there was little government control. This was because private ownership and free markets were widely accepted.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–1859) designed the first major railway, the Great Western Railway. It was built in the 1830s to connect London to Bristol. Even more important was George Hudson. He became Britain's "railway king" by combining many short lines. Since there was no government agency overseeing railways, Hudson set up a system. All the lines adopted it. It made connections easy for people and goods. This was done by standardizing how freight and people were transferred between companies. It also involved lending out freight cars. By 1849, Hudson controlled almost 30% of Britain's railway tracks.

By 1850, Britain had a well-connected and well-built railway system. It provided fast, on-time, and cheap movement of goods and people to every city and most rural areas. Freight costs for coal dropped to a penny per ton-mile. The system directly or indirectly employed tens of thousands of engineers, conductors, mechanics, and managers. This brought a new level of business skill that could be used in many other industries. It also helped many small and large businesses grow their role in the Industrial Revolution. Railways had a huge impact on industrialization. By lowering transport costs, they reduced costs for all industries moving supplies and finished goods. They also increased demand for all the things needed to build the railway system itself. The system kept growing. By 1880, there were 13,500 locomotives. Each carried 97,800 passengers a year, or 31,500 tons of freight.

Second Industrial Revolution

During the First Industrial Revolution, the factory owner became more important than the merchant. In the late 1800s, control of large industries moved to financiers. This led to "financial capitalism" and the rise of large companies. Huge industrial empires were created. Their assets were controlled by people who were not directly involved in making things. This was a key feature of this new phase.

New products and services also greatly increased international trade. Better steam engines and cheap iron (and later steel) meant slow sailing ships could be replaced by steamships. Electricity and chemical industries became important. However, Britain was behind the U.S. and Germany in these areas.

Large companies joining together, mergers, and new technologies were mixed blessings for British business. This was especially true for the increased use of electric power and internal combustion engines. These developments greatly increased production and lowered costs. As a result, production often made more goods than people in Britain wanted to buy.

By the 1870s, financial companies in London had a lot of control over industry. This made policy-makers more worried about protecting British investments overseas. These investments were mainly in foreign government bonds and projects like railways.

At the end of the Victorian era, the service sector (like banking, insurance, and shipping) started to grow more important. Manufacturing became less important. In the late 1700s, the UK saw stronger growth in the service sector than in industry. Industry grew by only 2%, while service sector jobs increased by 9%.

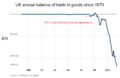

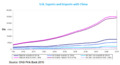

Foreign Trade

Foreign trade tripled between 1870 and 1914. Most of this trade was with other industrialized countries. Britain was the world's largest trading nation in 1860. But by 1913, it had lost ground to both the United States and Germany. British and German exports in that year were each $2.3 billion. Those of the United States were over $2.4 billion.

As foreign trade grew, more of it went outside Europe. In 1840, £7.7 million of its exports and £9.2 million of its imports were from outside Europe. In 1880, these figures were £38.4 million and £73 million. Europe's economic connections with the wider world were growing. In many cases, colonial control followed private investment, especially in raw materials and farming. Trade between continents was a larger part of global trade in this era than in the late 1900s.

Exporting Capital

London became even stronger as the world's financial capital. Exporting capital (money for investment) was a major part of the British economy from 1880 to 1913. This was known as the "golden era" of international finance.

Investment was especially high in the independent nations of Latin America. These countries wanted better infrastructure, like railways built by the British, ports, and telegraph and telephone systems. British merchants controlled trade in the region. Not all investments paid off. For example, mines in Sudan lost money. By 1913, Britain's overseas assets totaled about four billion pounds.

Business Practices

Britain continued its free trade policy. This was even though its main rivals, the U.S. and Germany, used high tariffs. American heavy industry grew faster than Britain's. By the 1890s, American machinery and other products were pushing British goods out of the world market.

New business practices in management and accounting helped large companies run more efficiently. For example, in steel, coal, and iron companies, 19th-century accountants used detailed accounting systems. These systems calculated output, yields, and costs to help managers. South Durham Steel and Iron was a large company that owned mines, mills, and shipyards. Its managers used traditional accounting methods to lower production costs and increase profits. In contrast, one of its competitors, Cargo Fleet Iron, used mass production methods. Cargo Fleet set high production goals and developed a new, complex accounting system. This system measured and reported all costs during production. However, problems getting coal and failing to meet production goals forced Cargo Fleet to stop its aggressive system. It returned to the methods South Durham Steel was using.

The American "invasion" of the British market demanded a response. Tariffs were not put in place until the 1930s. So, British business people had to either lose their market or modernize their operations. The shoe industry faced more imports of American footwear. Americans took over the market for shoe machinery. British companies realized they had to compete. They re-examined their traditional work methods, how they used labor, and their worker relations. They also rethought how to sell shoes based on fashion trends.

Imperialism

After losing the American colonies in 1776, Britain built a "Second British Empire." This empire was based in colonies in India, Asia, Australia, and Canada. The most important part was India. In the 1750s, a private British company called the East India Company, with its own army, took control of parts of India. In the 1800s, the Company's rule spread across India after pushing out the Dutch, French, and Portuguese. By the 1830s, the Company was more like a government and had given up most of its business in India. But it was still privately owned. After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the government closed the Company. It took direct control of British India and the Company's armies.

Free trade (with no tariffs and few trade barriers) was introduced in the 1840s. The powerful Royal Navy protected this economic empire. This empire also included very close economic ties with independent nations in Latin America. This informal economic empire has been called "The Imperialism of Free Trade."

Many independent business people expanded the Empire. For example, Stamford Raffles of the East India Company founded the port of Singapore in 1819. Businessmen who wanted to sell Indian opium in China led to the Opium War (1839–1842). This war led to the establishment of British colonies at Hong Kong. One adventurer, James Brooke, became the Rajah of the Kingdom of Sarawak in North Borneo in 1842. His kingdom joined the Empire in 1888. Cecil Rhodes built a very profitable diamond empire in South Africa. There were also great riches in gold. But this led to expensive wars with the Dutch settlers known as Boers.

The East India Company's possessions in India, under direct rule of the Crown from 1857, were the heart of the Empire. Because of an efficient tax system, India paid for its own administration and the cost of the large British Indian Army. However, in terms of trade, India brought only a small profit for British business.

There was pride in the Empire. Talented young Britons competed for jobs in the Indian Civil Service and other overseas career opportunities. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 was a vital economic and military link. To protect the canal, Britain expanded further. It took control of Egypt, Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, Cyprus, Palestine, Aden, and British Somaliland. None of these were very profitable until oil was discovered in the Middle East after 1920. Some military action was involved. Sometimes there was a risk of conflict with other empires seeking the same land. All these incidents were resolved peacefully.

Historians Cain and Hopkins argue that the periods of expansion abroad were closely linked to the growth of the British economy at home. They say that the changing balance of social and political forces under imperialism, and the varying intensity of Britain's economic and political rivalry with other powers, must be understood by looking at domestic policies. "Gentlemen capitalists," representing Britain's landed gentry and London's financial institutions, largely shaped and controlled Britain's imperial ventures in the 1800s and early 1900s. Industrial leaders played a smaller role and depended on these gentlemen capitalists.

Britain's Economy: 1900-1945

By 1900, the United States and Germany had developed large industries. Britain's economic advantage had lessened. London remained the world's financial and business capital until New York challenged it after 1918.

The Edwardian Era (1900–1914)

The Edwardian era (1901-1910) was a time of peace and wealth. There were no major economic downturns, and prosperity was widespread. Britain's growth rate, manufacturing output, and total economic output (but not per person) fell behind its rivals, the United States and Germany. However, Britain still led the world in trade, finance, and shipping. It also had strong manufacturing and mining industries. The industrial sector was slow to adapt to global changes. Among the elite, there was a clear preference for leisure over starting new businesses.

However, there were major achievements. The City of London was the world's financial center. It was much more efficient and widespread than New York, Paris, or Berlin. Britain had built up huge overseas investments in its formal Empire and in its informal empire in Latin America and other nations. It had large financial holdings in the United States, especially in railways. These assets were vital for paying for supplies in the first years of the World War. Life in cities was improving, and prosperity was very visible. Working-class people began to demand more political power. But major industrial unrest over economic issues was not high until about 1908.

First World War

World War I led to a decline in economic production. A lot of resources were moved to making weapons. It forced Britain to use up its financial savings and borrow large amounts from the U.S. Shipments of American raw materials and food allowed Britain to feed itself and its army while keeping its factories running. The financing was generally successful. London's strong financial position helped keep inflation from getting too bad, unlike in Germany. Overall, what people bought went down by 18% from 1914 to 1919.

Trade unions were encouraged. Membership grew from 4.1 million in 1914 to 6.5 million in 1918. It peaked at 8.3 million in 1920 before falling to 5.4 million in 1923. In Scotland, the shipbuilding industry grew by a third. Women were available, and many worked in munitions factories and took other jobs at home that men had left.

After the War: Stagnation

Britain suffered huge human and material losses in the First World War. This included 745,000 soldiers killed and 24,000 civilians. 1.7 million people were wounded. The total loss of shipping was 7.9 million tons. The financial cost to the Empire was £7,500 million. Germany owed billions in payments, but Britain in turn owed the U.S. billions in loan repayments.

When war orders ended, a serious economic downturn hit by 1921-22. The entire decade was one of stagnation. Skilled workers were especially hard hit because there were few other uses for their specialized skills. In depressed areas, things like poor health, bad housing, and long-term mass unemployment showed a deep economic problem. The heavy reliance on old, heavy industries and mining was a central issue, and no one had good solutions. This despair made local business and political leaders ready to accept new government economic planning during the Second World War.

In 1919, Britain reduced working hours in major industries to a 48-hour week for factory workers. Historians have debated if this lowered worker output and contributed to the slump.

By 1921, over 3 million Britons were unemployed because of the postwar economic downturn. By 1926, the economy was still struggling. The general strike that year did not help. Industrial relations improved briefly. But then came the Wall Street stock market crash in October 1929. This started the worldwide Great Depression. Unemployment was less than 1.8 million at the end of 1930. But by the end of 1931, it had risen sharply to over 2.6 million. By January 1933, over 3 million Britons were unemployed. This was more than 20% of the workforce. Unemployment was over 50% in some parts of the country, especially in South Wales and the north-east of England. The rest of the 1930s saw a moderate economic recovery. This was helped by private housing. The unemployment rate fell to 10% in 1938, half of what it was five years earlier.

Steel Industry

From 1800 to 1870, Britain produced more than half of the world's pig iron. It led the way in finding ways to make steel. In 1880, Britain produced 1.3 million tons of steel. In 1893, it produced 3 million tons. By 1914, output was 8 million tons. Germany caught up in 1893 and produced 14 million tons in 1914. After 1900, the U.S. led global steel production, while the British industry struggled.

Britain's steel industry brought in experts to analyze and suggest ways to improve production. The industry made important technical advances. It developed new types of strong steel alloys. It used electric furnaces and other new ideas. The industry trained a group of experts who helped large firms become scientifically self-sufficient.

Coal Mining

Politics became a central issue for coal miners. Their organization was helped by living in remote villages where mining was the only industry. The Miners' Federation of Great Britain formed in 1888. It had 600,000 members in 1908. Much of the early Labour Party's politics came from coal-mining areas.

The General Strike of 1926

In April 1926, mine owners locked out the miners. The miners had refused demands for longer hours and less pay. This was because prices were falling as oil started to replace coal. The general strike was led by the TUC (Trades Union Congress) to help the coal miners. But it failed. It was a nine-day nationwide walkout of one million railway workers, transport workers, printers, dockers, and steelworkers. They supported the 1.5 million coal miners who had been locked out. The government had given money to the industry in 1925, but it was not enough to fix the problems. The TUC hoped the government would step in to reorganize the industry and increase the money given. The Conservative government had stored supplies. Essential services continued with middle-class volunteers. All three major political parties were against the strike. The general strike itself was mostly peaceful. But the miners' lockout continued, and there was violence in Scotland. It was the only general strike in British history. TUC leaders like Ernest Bevin thought it was a mistake. Most historians see it as a unique event with few long-term effects. But some say it helped more working-class voters move to the Labour Party. The Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act 1927 made general strikes illegal. It also stopped union members from automatically paying money to the Labour Party. That act was mostly removed in 1946.

Coal continued to be a struggling industry. The best coal seams were used up, and it became harder to mine the rest. The Labour government in 1947 took control of the coal industry. It created the National Coal Board. This gave miners some control over the mines through their influence in the Labour party and government. However, by then, the best seams were gone, and coal mining was declining. Coal production was 50 million metric tons in 1850. It was 149 million in 1880, 269 million in 1910, 228 million in 1940, and 153 million in 1970. The peak year was 1913, with 292 million tons. Mining employed 383,000 men in 1851, 604,000 in 1881, and 1,202,000 in 1911.

The Great Depression (1929–1939)

In 1929, the Wall Street Crash affected Britain. This led to Britain leaving the Gold Standard. Britain had supported the idea of a free market when its economy was strong. But it slowly moved towards using tariffs to protect its industries. By the early 1930s, the depression again showed the economic problems Britain faced. Unemployment soared during this time. It went from just over 10% in 1929 to more than 20% (over 3 million workers) by early 1933. However, it had fallen to 13.9% by the start of 1936.

In politics, the economic problems led to the rise of radical groups. These groups promised solutions that traditional political parties could no longer provide. In Britain, this was seen with the rise of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and the Fascists under Oswald Mosley. However, their political power was limited. They never truly threatened the traditional political parties in the UK. The Conservatives returned to power in 1935. This was after six years of the first Labour-led government under Ramsay MacDonald.

Tourism grew quickly between the wars. This was because more middle-class people had cars and went on holidays. Seaside resorts like Blackpool, Brighton, and Skegness were very popular. However, tourist places that served only the very rich or American tourists saw a drop in profits. This was especially true during the Great Depression.

Second World War

In the Second World War, 1939–45, Britain was very successful at getting its people at home ready for the war. It used the largest possible number of workers. It made sure output was as high as possible. It put the right skills to the right tasks. It also kept up the morale of the people. Much of this success was because women were systematically organized. They worked as factory workers, soldiers, and housewives. This was made mandatory after December 1941. Women supported the war effort and made the rationing of consumer goods successful.

Industrial production was changed to make weapons, and output soared. For example, in steel, the government's Materials Committee tried to balance the needs of civilian departments and the War Department. But military needs came first. The highest priority went to making aircraft. The Royal Air Force was under constant heavy German attack. The government decided to focus on only five types of aircraft to make as many as possible. These aircraft received special priority. This included getting materials, equipment, and even diverting parts and resources from other types of aircraft. Workers were moved from other aircraft work to factories making these specific types. Cost was not a concern. The delivery of new fighter planes rose from 256 in April to 467 in September 1940. This was more than enough to cover losses. Fighter Command won the Battle of Britain in October with more aircraft than it had at the start. Starting in 1941, the U.S. provided weapons through Lend-Lease. This totaled $15.5 billion.

After war broke out between Britain and Germany in September 1939, Britain put in place exchange controls. The British Government used its gold reserves and dollar reserves to pay for weapons, oil, raw materials, and machinery, mostly from the U.S. By late 1940, the amount of British exports was down 37% compared to 1935. Although the British Government had ordered nearly $10 billion worth of goods from America, Britain's gold and dollar reserves were almost gone. The U.S. government was committed to helping Britain economically. In early 1941, it passed Lend-Lease. Through this, America would give Britain supplies totaling $31.4 billion, which never had to be repaid.

Britain's Economy: 1945 to 2001

In the 1945 general election, just after the war in Europe, the Labour Party led by Clement Attlee won a huge victory. They introduced big changes to the British economy. Taxes were increased, industries were taken over by the state (nationalized), and a welfare state was created. This included national health care, pensions, and social security.

The next 15 years saw some of the fastest growth Britain had ever experienced. The economy recovered from the war and then grew rapidly beyond its previous size. The economy became stronger, especially after the Conservatives returned to government in 1951. Winston Churchill led them until he retired in 1955. However, the Suez crisis in 1956 weakened the government's reputation and Britain's global standing. This led to Churchill's replacement by Harold Macmillan.

By 1959, tax cuts had helped improve living standards. They also led to a strong economy and low unemployment. In October 1959, the Conservatives won their third election in a row with a much larger majority. This made the public and media doubt Labour's chances of winning future elections.

Britain's economy remained strong with low unemployment into the 1960s. But towards the end of the decade, this growth started to slow. Unemployment began to rise again. Harold Wilson, the Labour leader, had ended 13 years of Conservative rule with a small win in 1964. He increased his majority in 1966. But he was surprisingly voted out of power in 1970. The new Conservative government was led by Edward Heath.

During the 1970s, Britain suffered a long period of economic problems. It was troubled by rising unemployment, frequent strikes, and high inflation. Neither the Conservative government (1970-1974) nor the Labour government that followed (led by Harold Wilson and then James Callaghan) could stop the country's economic decline. Inflation went over 20% twice in the 1970s and was rarely below 10%.

Unemployment went over 1 million by 1972. It rose even higher by the end of the decade, passing 1.5 million in 1978. The winter of 1978/79 brought many public sector strikes. This period was known as the Winter of Discontent. It led to the fall of Callaghan's Labour government in March 1979.

This led to the election of Margaret Thatcher. She had replaced Edward Heath as Conservative leader in 1975. She reduced the government's role in the economy. She also weakened the power of trade unions. The last two decades of the 20th century saw more service providers and less manufacturing and heavy industry. Some parts of the economy were also sold off to private companies. Some people call this a 'Third Industrial Revolution', but this term is not widely used.

After World War II: The Age of Austerity (1945–1951)

After World War II, the British economy had lost a huge amount of wealth again. Its economy was completely focused on war needs. It took some time to change back to peaceful production. The United States had negotiated during the war to open up trade after the war. This was to get into markets that had been closed to it, including the British Empire's currency area. This was planned through the Atlantic Charter of 1941 and the Bretton Woods system in 1944. The U.S. also gained economic power because Britain's economy was weakened.

Right after the war ended, the U.S. stopped its free Lend-Lease program. But it did give the UK a long-term, low-interest loan of $4.33 billion. The winter of 1946–1947 was very harsh. It cut down production and led to coal shortages. This again affected the economy. By August 1947, when the British currency was supposed to be freely convertible, the economy was not strong enough. When the Labour Government made the currency convertible, people quickly exchanged British pounds for U.S. dollars. The dollar was seen as the new, more powerful and stable currency. This hurt the British economy, and the convertibility was stopped within weeks. By 1949, the British pound was too highly valued and had to be devalued. The U.S. began Marshall Plan grants (mostly grants with some loans). These pumped $3.3 billion into the economy. They also forced business people to modernize their management.

Nationalization

The Labour Governments from 1945–1951 put in place a political plan based on collectivism. This included the nationalization of industries. This meant the state took control of them. It also included state control of the economy. Both world wars had shown the possible benefits of more state involvement. This shaped the future direction of the post-war economy. It was mostly supported by the Conservatives. However, the initial hopes for nationalization were not fully met. More flexible ideas about economic management appeared, such as state guidance rather than state ownership. But the basic idea remained the same: using economic theories and continued state involvement.

The idea of nationalizing the coal mines had been accepted by both owners and miners before the 1945 elections. The owners were paid £165 million. The government set up the National Coal Board to manage the coal mines. It loaned the board £150 million to modernize the system. The coal industry had been in poor condition for many years, with low production. In 1945, there were 28% more workers in coal mines than in 1890, but the yearly output was only 8% greater. Young people avoided working in the mines. Between 1931 and 1945, the percentage of miners over 40 years old rose from 35% to 43%. 24,000 miners were over 65 years old. The number of surface workers decreased by only 3,200 between 1938 and 1945. But during the same time, the number of underground workers fell by 69,600. This greatly changed the balance of labor in the mines. Accidents, breakdowns, and repairs in the mines were almost twice as costly in terms of production in 1945 as they had been in 1939. This was probably a result of the war. Output in 1946 averaged 3.3 million tons weekly. By summer 1946, it was clear that the country faced a coal shortage for the coming winter. Stockpiles of 5 million tons were too low. Nationalization showed a lack of preparation for public ownership. It also showed a failure to stabilize the industry before the change. There were also no strong reasons to keep or increase coal production to meet demand.

The loss of the Empire and the material losses from two world wars affected Britain's economy. First, its traditional markets changed as Commonwealth countries made their own trade deals with local or regional powers. Second, Britain's early gains in the world economy declined. This was because countries whose infrastructure was badly damaged by war rebuilt and reclaimed their share of world markets. Third, the British economy changed. It shifted towards a service sector economy from its manufacturing and industrial past. This left some regions with economic problems. Finally, part of the political agreement was to support the Welfare State and Britain's role in the world. Both of these needed money from taxes and a strong economy to provide those taxes.

Prosperity in the 1950s

The 1950s and 1960s were prosperous times. The economy continued to modernize. For example, the first motorways were built. Britain kept and increased its financial role in the world economy. It used the English language to promote its education system to students worldwide. Unemployment was relatively low during this time. The standard of living continued to rise. More new private and council housing was built, and the number of poor quality homes decreased. Churchill and the Conservatives were back in power after the 1951 elections. But they mostly continued the welfare state policies that the Labour Party had started in the late 1940s.

During the "golden age" of the 1950s and 1960s, unemployment in Britain was only about 2%. As prosperity returned, Britons focused more on family. Leisure activities became more available to more people after the war. Holiday camps, which first opened in the 1930s, became popular holiday spots in the 1950s. People increasingly had money for their hobbies. The BBC's early television service got a big boost in 1953 with the coronation of Elizabeth II. It attracted 20 million viewers worldwide, plus tens of millions more by radio. This encouraged middle-class people to buy televisions. In 1950, only 1% owned TVs. By 1965, 25% did. As strict money rules eased after 1950 and consumer demand kept growing, the Labour Party hurt itself by rejecting consumerism.

Small local shops were increasingly replaced by chain stores and shopping centres. These offered a wide variety of goods, smart advertising, and frequent sales. Cars became a significant part of British life. City centers became congested, and new buildings spread along many major roads. These problems led to the idea of the green belt to protect the countryside from new housing developments.

The period after the war saw a huge rise in the average standard of living. Average real wages rose by 40% from 1950 to 1965. Workers in traditionally low-paid jobs saw a particularly big improvement in their wages and living standards. In terms of what people bought, there was more equality. This was especially true as rich landowners struggled to pay taxes and had to spend less. As a result of wage rises, consumer spending also increased by about 20% during the same period. Economic growth remained at about 3%. Also, the last food rations ended in 1954. Rules on buying things on credit were also relaxed that year. Because of these changes, many working-class people could buy consumer goods for the first time.

Access to various extra benefits improved. In 1955, 96% of manual laborers could take two weeks' paid holiday. This was up from 61% in 1951. By the end of the 1950s, Britain had become one of the world's richest countries. By the early 1960s, most Britons enjoyed a level of wealth that only a small number of people had known before. For young, single people, there was, for the first time in decades, extra money for leisure, clothes, and luxuries. In 1959, Queen magazine said that "Britain has launched into an age of unparalleled lavish living." Average wages were high, and jobs were plentiful. People saw their personal wealth climb even higher. Prime Minister Harold Macmillan claimed that "the luxuries of the rich have become the necessities of the poor."

The most popular item for housewives was a washing machine. Ownership jumped from 18% in 1955 to 29% in 1958, and 60% in 1966. By 1963, 82% of all private homes had a television, 72% a vacuum cleaner, and 30% a refrigerator. John Burnett notes that ownership had spread down the social scale. The gap in consumption between professional and manual workers had narrowed a lot. The availability of home comforts steadily improved in the later decades of the century. From 1971 to 1983, homes with their own bath or shower rose from 88% to 97%. Those with an indoor toilet rose from 87% to 97%. Also, the number of homes with central heating almost doubled during that same period, from 34% to 64%. By 1983, 94% of all homes had a refrigerator, 81% a color television, 80% a washing machine, 57% a deep freezer, and 28% a tumble-drier.

However, from a European perspective, Britain was not keeping up. Between 1950 and 1970, most countries in the European Common Market surpassed Britain. This was in terms of the number of telephones, refrigerators, televisions, cars, and washing machines per 100 people. Education grew, but not as fast as in rival nations. By the early 1980s, about 80% to 90% of school leavers in France and West Germany received vocational training. This compared to 40% in the United Kingdom. By the mid-1980s, over 80% of students in the United States and West Germany, and over 90% in Japan, stayed in education until age eighteen. This compared to barely 33% of British students. In 1987, only 35% of 16- to 18-year-olds were in full-time education or training. This compared to 80% in the United States, 77% in Japan, 69% in France, and 49% in the United Kingdom.

The Sixties and Seventies (1960–1979)

Deindustrialization

Deindustrialization meant many mines, heavy industries, and factories closed. This led to the loss of many high-paying working-class jobs. Some businesses had always closed, and new ones opened. But the situation after 1973 was different. There was a worldwide energy crisis and many cheap manufactured goods came from Asia. Coal mining slowly collapsed and finally disappeared in the 21st century. Railways were old, more textile mills closed than opened, steel jobs fell sharply, and the car industry almost vanished, except for some luxury cars. People reacted in different ways. Some felt sad about a glorious industrial past or the old British Empire. Others looked to the EU for help. Some turned to a strong English identity to deal with their new economic problems. By the 21st century, these problems grew enough to have a political impact. The UK Independence Party (Ukip), based in white working-class towns, gained more votes. It warned against the dangers of immigration. These political effects led to the unexpected vote for Brexit in 2016.

Stagnation

As problems grew in the 1960s, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan's slogan, "(most of) our people have never had it so good," seemed less true. The Conservative Government tried to control the economy. It aimed to stop inflation from getting out of control without stopping economic growth. Growth continued to struggle. It was only about half the rate of Germany or France at the same time. However, industry had remained strong for nearly 20 years after the war. Extensive housebuilding and construction of new commercial and public buildings also helped keep unemployment low during this time.

Comparing economic prosperity (using total output per person), Britain's record showed a steady decline. It fell from seventh place in the world in 1950, to 12th in 1965, to 20th in 1975. Labour politician Richard Crossman, after visiting prosperous Canada, returned to England with a:

- sense of restriction, yes, even of decline, the old country always teetering on the edge of a crisis, trying to keep up appearances, with no confident vision of the future.

Economists gave four main reasons. The "early start" theory said Britain's rivals were doing well because they were still moving many farm workers to better-paying jobs. Britain had done this in the 1800s. A second theory focused on "rejuvenation by defeat." This meant Germany and Japan had been forced to rebuild and rethink their economies after being defeated. The third idea stressed the drag of "Imperial distractions." This said that responsibilities to its large empire hurt the home economy, especially through defense spending and economic aid. Finally, the "institutional failure" theory blamed problems like lack of consistency, unpredictability, and class envy. This last theory blamed trade unions, private schools, and universities for keeping an anti-industry attitude among the elite.

Labour's Response

The 1970s saw the excitement and radicalism of the 1960s fade away. Instead, there was a growing series of economic crises. These were marked especially by labor union strikes. The British economy fell further and further behind European and world growth. This led to a major political crisis. There was a Winter of Discontent in the winter of 1978–79. During this time, there were widespread strikes by public sector unions. This caused serious problems and angered the public.

Historians Alan Sked and Chris Cook have summarized what most historians agree on about Labour in power in the 1970s:

- If Wilson's record as prime minister was soon felt to have been one of failure, that sense of failure was powerfully reinforced by Callahan's term as premier. Labour, it seemed, was incapable of positive achievements. It was unable to control inflation, unable to control the unions, unable to solve the Irish problem, unable to solve the Rhodesian question, unable to secure its proposals for Welsh and Scottish devolution, unable to reach a popular modus vivendi with the Common Market, unable even to maintain itself in power until it could go to the country and the date of its own choosing. It was little wonder, therefore, that Margaret Thatcher resoundingly defeated it in 1979.

The Labour Party under Harold Wilson from 1964–1970 could not find a solution either. Eventually, it was forced to devalue the pound again in 1967. Economist Nicholas Crafts says Britain's relatively slow growth in this period was due to a lack of competition in some parts of the economy, especially in nationalized industries. It was also due to poor relations between workers and management, and not enough job training. He writes that this was a period of government failure. It was caused by a poor understanding of economic theory, short-term thinking, and a failure to challenge powerful groups.

Both political parties had decided that Britain needed to join the European Economic Community (EEC) to revive its economy. This decision came after forming a European Free Trade Association (EFTA) with other non-EEC countries. This provided little economic boost to Britain's economy. Trade levels with the Commonwealth halved between 1945 and 1965 to around 25%. Meanwhile, trade with the EEC had doubled during the same period. Charles de Gaulle vetoed Britain's attempt to join in 1963 and again in 1967.

The general election in June 1970 saw the Conservatives, now led by Edward Heath, surprisingly return to government. Opinion polls had suggested a third Labour victory. Unemployment was still low at this stage, standing at 3% nationally.

However, with Britain's economy declining during the 1960s, trade unions began to strike. This led to a complete breakdown with both Harold Wilson's Labour Government and later with Edward Heath's Conservative Government (1970–1974). In the early 1970s, the British economy suffered even more. Strikes by trade unions, plus the effects of the 1973 oil crisis, led to a Three-Day Week in 1973-74. Despite a brief calm period negotiated by the recently re-elected Labour Government of 1974, a breakdown with the unions happened again in 1978. This led to the Winter of Discontent. It eventually led to the end of the Labour Government, then led by James Callaghan. The extreme industrial conflict, along with rising inflation and unemployment, led Britain to be called the "sick man of Europe".

Unemployment had also risen during this difficult period for the British economy. Unemployment reached 1.5 million in 1978. This was nearly three times the figure of a decade earlier. The national rate went over 5% for the first time since the war. It had not fallen below 1 million since 1975 and has rarely dropped below 1.5 million since.

Also in the 1970s, oil was found in the North Sea, off the coast of Scotland. However, its contribution to the UK economy was limited. This was because the money was needed to pay for rising national debt and welfare payments for the growing number of unemployed people.

The Thatcher Era (1979–1990)

The election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 marked a new approach to economic policy. This included selling off state-owned industries (privatization) and reducing government rules (deregulation). It also involved changes to industrial relations and taxes. Competition policy was emphasized instead of industrial policy. The resulting loss of industries and structural unemployment were largely accepted. Thatcher's conflicts with the unions reached their peak in the Miners' Strike of 1984.

The Government used policies to reduce inflation. It also cut public spending. These measures were put in place during the recession of 1980/81. As a result, unemployment went over 2 million in late 1980. It reached 2.5 million the following spring. By January 1982, unemployment had reached 3 million for the first time since the early 1930s. However, this time the figure was a smaller percentage of the workforce (around 12.5% instead of over 20%). In areas hit hard by the loss of industry, unemployment was much higher. It was close to 20% in Northern Ireland and over 15% in many parts of Wales, Scotland, and northern England. The highest unemployment actually came about two years after the recession ended and growth had returned. In April 1984, unemployment was just under 3.3 million.

One historian described Thatcher's time as an "industrial holocaust." Britain's industrial capacity decreased by a quarter between 1980 and 1984. Major state-controlled firms were privatized. These included British Aerospace (1981), British Telecom (1984), British Leyland (1984), Rolls-Royce (1987), and British Steel Corporation (1988). The electricity, gas, and English water industries were broken up and sold off. Exchange controls, which had been in place since the war, were removed in 1979. British net assets abroad grew about nine times. They went from £12 billion at the end of 1979 to nearly £110 billion at the end of 1986. This was a record high after the war and second only to Japan. Selling off nationalized industries increased share ownership in Britain. The percentage of adults owning shares went up from 7% in 1979 to 25% in 1989. The Single European Act (SEA), signed by Margaret Thatcher, allowed goods to move freely within the European Union area. The idea was that this would boost competition in the British economy and make it more efficient.

The early 1980s recession saw unemployment rise above three million. But the recovery that followed, with annual growth of over 4% in the late 1980s, led to talk of a British 'economic miracle'. There is much debate about whether Thatcher's policies caused the boom in Britain in the 1980s. North Sea oil has been identified as a major factor in the economic growth in the mid and late 1980s. However, many of the economic policies put in place by the Thatcher governments have been kept since. Even the Labour Party, which had once been so against these policies, had dropped all opposition to them by the late 1990s. This was when they returned to government after nearly 20 years out of power.

Indeed, the Labour Party of the 1980s had moved to the left after Michael Foot became leader in 1980. This led to a split in the party. Some members formed the centrist Social Democratic Party. This party formed an alliance with the Liberals. They ran in two general elections, with disappointing results. They then merged in 1988 to form the Liberal Democrats. The Conservatives were re-elected in 1983 and again in 1987. They had a majority of over 100 seats both times.

By the end of 1986, Britain was starting an economic boom. Unemployment fell below 3 million and reached a 10-year low of 1.6 million by December 1989. However, economic growth slowed down in 1989. Inflation was nearing 10%, and fears of an upcoming recession were common in the news. Interest rates were increased by the government to try to control inflation.

The Major Years (1990–1997)

In November 1990, Margaret Thatcher stepped down as Prime Minister. She had lost the support of Conservative Party Members of Parliament. John Major was elected as her replacement. The government's popularity was also falling after the introduction of a new tax earlier that year. Unemployment was also starting to rise again as another recession loomed. Opinion polls suggested that the next general election could be won by Labour, led by Neil Kinnock since 1983.

Despite several major economies shrinking in late 1989, the British economy continued to grow well into 1990. The first quarterly shrinkage happened in the third quarter of the year. By then, unemployment was starting to creep up again after four years of falling. The start of another recession was confirmed in January 1991. Interest rates had been increased between 1988 and 1990 to control inflation. Inflation topped 10% in 1990 but was below 3% by the end of 1992.

Economic growth did not return until early 1993. But the Conservative government, which had been in power since 1979, managed to win re-election in April 1992. They fended off a strong challenge from Neil Kinnock and Labour. However, their majority was much smaller.

The early 1990s recession was officially the longest in Britain since the Great Depression, about 60 years earlier. However, the fall in output was not as sharp as in the Great Depression or even the early 1980s recession. It had started in 1990, and the end of the recession was not officially declared until April 1993. By then, nearly 3 million people were unemployed.

The British pound was linked to EU exchange rates, using the Deutsche Mark as a base. This was part of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM). However, this led to disaster for Britain. The rules of the ERM put pressure on the pound, leading to a rapid selling of the currency. Black Wednesday in September 1992 ended British membership of the ERM. It also damaged the Conservatives' reputation for good economic management. This contributed to the end of 18 years of continuous Conservative government in 1997. The party had long been divided over European issues, and many of these divisions within the party had still not been fixed by 1997.

Despite the downfall of the Conservative government, it had overseen a strong economic recovery. Unemployment had fallen by over 1 million since late 1992 to 1.7 million by the time of their election defeat just over four years later. Inflation also remained low. The ERM exit in 1992 was followed by a gradual decrease in interest rates in the years that followed.

New Labour (1997 to 2001)

From May 1997, Tony Blair's newly elected Labour government stuck with the Conservatives' spending plans. The Chancellor, Gordon Brown, gained a reputation as the "prudent Chancellor." He helped to create new confidence in Labour's ability to manage the economy. This was after the economic problems of earlier Labour governments. One of the first things the new Labour government did was to give the power to set interest rates to the Bank of England. This effectively stopped using interest rates as a political tool. Control of the banks was given to the Financial Services Agency. Labour also introduced the minimum wage to the United Kingdom. This has been raised every year since it started in April 1999. The Blair government also introduced strategies to cut unemployment. This included expanding the public sector. Unemployment was consistently below 1.5 million during the first half of the 2000s. This level had not been seen since the late 1970s. However, the government never managed to get unemployment back to the six-figure numbers seen for most of the 30 years after World War II.

The 21st Century

In the Labour Party's second term, starting in 2001, the party won another huge victory. It increased taxes and borrowing. The government wanted the money to increase spending on public services, especially the National Health Service. They said it was suffering from not enough funding. The economy shifted away from manufacturing, which had been declining since the 1960s. It grew based on the services and finance sectors. The public sector continued to expand. The country was also at war, first with Afghanistan (invading in 2001) and then Iraq (in 2003). These wars were controversial with the British public. Spending on both reached several billion pounds a year. The government's popularity began to slide. However, it did manage to win a third general election under Blair in 2005, with a smaller majority. Blair stepped down two years later after a decade as prime minister. He was replaced by the former chancellor Gordon Brown. This change of leader came at a time when Labour was starting to fall behind the Conservatives (now led by Theresa May) in opinion polls.

By this stage, unemployment had increased slightly to 1.6 million. However, the economy continued to grow. The UK continued to lose many manufacturing jobs. This was because companies faced financial problems or moved production overseas to save labor costs. This was very clear in the car industry. Companies like General Motors (Vauxhall) and Ford had greatly reduced their UK operations. Peugeot (the French carmaker) had completely left Britain. These closures led to thousands of job losses. The biggest single blow to the car industry came in 2005 when MG Rover went out of business. Over 6,000 jobs were lost at the carmaker alone. About 20,000 more were lost in related supply industries and dealerships. This was the largest collapse of any European carmaker in modern times.

Growth rates were consistently between 1.6% and 3% from 2000 to early 2008. Inflation was relatively steady at around 2%, but it did rise before the financial crash. The Bank of England's control of interest rates was a major reason for the stability of the British economy during that period. The pound continued to change value. It reached a low against the dollar in 2001 (at $1.37 per £1). But it rose again to about $2 per £1 in 2007. Against the Euro, the pound was steady at about €1.45 per £1. Since then, the effects of the Credit crunch have slowed down the economy. For example, in early November 2008, the pound was worth about €1.26. By the end of the year, it had almost reached parity, dropping at one point below €1.02 and ending the year at €1.04.

The 2008 Recession and Quantitative Easing

The UK entered a recession in the second quarter of 2008. It exited in the fourth quarter of 2009. Official figures showed that the UK had six quarters in a row of economic shrinkage. On January 23, 2009, government figures confirmed that the UK was officially in recession for the first time since 1991. It entered a recession in late 2008. This was accompanied by rising unemployment. Unemployment increased from 5.2% in May 2008 to 7.6% in May 2009. The unemployment rate among 18- to 24-year-olds rose from 11.9% to 17.3%. Although Britain initially lagged behind other major economies like Germany, France, Japan, and the US (which all returned to growth in mid-2009), the country eventually returned to growth in late 2009. On January 26, 2010, it was confirmed that the UK had left its recession. It was the last major economy in the world to do so. In the three months to February 2010, the UK economy grew by 0.4%. In mid-2010, the economy grew by 1.2%, the fastest rate in 9 years. In late 2010, figures showed the UK economy grew by 0.8%. This was the fastest growth for that quarter in 10 years.

On March 5, 2009, the Bank of England announced it would inject £200 billion of new capital into the British economy. This was through a process called quantitative easing. This was the first time this measure had been used in the United Kingdom's history. The Bank's Governor Mervyn King said it was not an experiment. The process would involve the Bank of England creating new money electronically. It would then use this money to buy government bonds, bank loans, or mortgages. The initial amount to be created was £75 billion. The Bank of England stated that the decision was made to prevent inflation from falling below the two percent target rate. Mervyn King also suggested there were no other money-related options left. This was because interest rates had already been cut to their lowest level ever of 0.5%.

As of late November 2009, the economy had shrunk by 4.9%. This made the 2008–2009 recession the longest since records began. In December 2009, revised figures showed that the economy shrank by 0.2% in the third quarter of 2009.

It has been suggested that the UK initially lagged behind its European neighbors because the UK entered the 2008 recession later. However, German GDP fell 4.7% year-on-year compared to the UK's 5.1%. Germany had also posted a second quarterly gain in GDP. Commentators suggest that the UK suffered a slightly longer recession than other large European countries. This was a result of government policy dating back to the Thatcher government of 1979. In this policy, UK governments moved away from supporting manufacturing and focused on the financial sector. The OECD predicted that the UK would grow 1.6% in 2010. The unemployment rate fell in late 2009. This made the UK the first of the three largest economies in the EU to do so.

Total economic output (GDP) decreased by 0.2% in the third quarter of 2009. This was after a decrease of 0.6% in the second quarter. There was a 2.4% decline in the first quarter of 2009. The economy had shrunk 5.9% from its peak before the recession began.

In October 2007, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) had predicted British GDP to grow by 3.1% in 2007 and 2.3% in 2008. However, GDP growth slowed to a fall of 0.1% in the second quarter of 2008. In September 2008, the OECD predicted that the UK economy would shrink for at least two quarters. It said this could be severe. It placed Britain's predicted performance last among the G7 leading economies. Six quarters later, the UK economy was still shrinking. This raised questions about the OECD's forecasting methods.

It has been argued that heavy government borrowing in the past led to a severe structural deficit. This was similar to previous crises. This would make the situation worse. It would also put the UK economy in a bad position compared to its OECD partners. Other OECD nations had more room to act because they had tighter financial control before the global downturn.

In May 2009, the European Commission (EC) stated: "The UK economy is now clearly experiencing one of its worst recessions in recent history." The EC expected GDP to decline 3.8% in 2009. It projected that growth would remain negative for the first three quarters of 2009. It predicted two quarters of "virtual stagnation" in late 2009 and early 2010. This would be followed by a gradual return to "slight positive growth by late 2010."

The FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 stock market indexes rose to their highest levels in a year on September 9, 2009. The FTSE 100 went above 5,000, and the FTSE 250 went above 9,000. On September 8, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research believed that the economy had grown by 0.2% in the three months to August. It was later proven wrong. In its view, the UK recession was officially over. However, it warned that "normal economic conditions" had not returned. On the same day, figures also showed UK manufacturing output rising at its fastest rate in 18 months in July. On September 15, 2009, the EU incorrectly predicted the UK would grow by 0.2% between July and September. On the same day, the governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, said the UK GDP was now growing. Unemployment had recently fallen in Wales.

Many commentators in the UK were sure that the UK would officially leave recession in the third quarter. They believed that all signs showed growth was very likely. However, government spending had not been enough to rescue the economy from recession at that point. Figures actually showed no growth in retail sales in September 2009. Industrial output declined by 2.5% in August. The revised UK figures confirmed that the economy shrank in the third quarter of 2009 by 0.2%. This was despite government spending on the car scrappage scheme. This scheme allowed owners of cars at least 10 years old to buy a new car at a reduced price in return for having their old car scrapped. It was very popular with drivers.

Yet this temporary dip was followed by a solid 0.4% growth in the fourth quarter.

The UK manufacturers' group, the EEF, asked for more money from the government. They said: "Without more support for business investment, it will be hard to see where growth will come from."

The economic downturn in 2008 and 2009 caused the Labour government's popularity to drop. Opinion polls all showed the Conservatives in the lead during this time. However, by early 2010, the gap between the parties was small enough to suggest that the upcoming general election would result in a hung parliament. This happened in May 2010. The Conservatives won the most seats in the election, 20 short of a majority. They formed a government in coalition with the Liberal Democrats. The new government had to make deep cuts to public spending in the following years. This was to deal with the high national debt that had built up during Labour's time in government. This meant that unemployment remained high, and the economy struggled to grow. However, a clear improvement finally happened in 2013. Economic growth and falling unemployment were sustained.

Moody's gave the UK an AAA credit rating in September 2010. It predicted stable finances, mainly due to government actions. It also reported that the economy was flexible to grow in the future. However, household debts and poor exports were big factors slowing growth, as was its financial sector.

After that, the economy shrank in 5 of the next 7 quarters. This meant zero net growth from the end of the recession in late 2009 to mid-2012. In 2010, the economy picked up and grew steadily. However, in the summer, the Eurozone crisis, centered on Greece, led to a second slowdown in all European countries. The Eurozone entered a double-dip recession that lasted from early 2011 to mid-2013. While the UK did not have a double-dip recession, it did experience stagnant growth. The first half of 2012 saw inflation ease and business confidence increase. But some basic weaknesses remained, most notably a decline in the productivity of British businesses.