History of Australia facts for kids

The history of Australia tells the story of the land and people of the Australian continent.

People called Indigenous Australians first arrived by sea from Maritime Southeast Asia between 50,000 and 65,000 years ago. They spread across the whole continent, from the northern rainforests to the central deserts and the islands of Tasmania. Their spiritual, artistic, and musical traditions are some of the oldest still existing in human history.

The first Torres Strait Islanders, who are different from Aboriginal people, came from what is now Papua New Guinea about 2,500 years ago. They settled in the Torres Strait islands and the Cape York Peninsula.

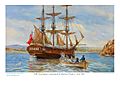

The first Europeans known to land in Australia were Dutch sailors led by Willem Janszoon in 1606. Later that year, Spanish explorer Luís Vaz de Torres sailed through what is now called Torres Strait. Many other Dutch explorers mapped the western and southern coasts in the 1600s, calling the continent New Holland. Macassan traders from Indonesia also visited Australia's northern coasts after 1720. In 1770, Lieutenant James Cook mapped the east coast for Great Britain. He suggested that Botany Bay (near modern Sydney) would be a good place for a colony.

The First Fleet of British ships arrived at Botany Bay in January 1788. They came to set up a penal colony, which was a place to send people who had committed crimes. Over the next 100 years, the British started more colonies across Australia. European explorers also travelled into the continent's centre. During this time, Aboriginal people suffered greatly. Many died from new diseases brought by Europeans and from conflicts with the colonists.

Gold rushes and farming helped Australia become rich. From the mid-1800s, the six British colonies in Australia began to govern themselves with their own parliaments. In 1901, the colonies voted to join together in a federation, forming modern Australia. Australia fought alongside Britain in the two World Wars. During World War II, when Imperial Japan threatened, Australia became a strong ally of the United States. After World War II, trade with Asia grew, and a large immigration program brought over 6.5 million people from all over the world. By 2020, Australia's population grew to more than 25.5 million, with 30% of people born overseas.

Contents

- Indigenous Australia: The First People

- Early European Explorers in Australia

- British Colonisation of Australia

- From Self-Rule to Federation

- Federation: The Birth of a Nation

- First World War: A Nation Forged in Conflict

- Between the World Wars

- Second World War: A New Alliance

- Post-War Australia: Growth and Change

- Vietnam War: A Divisive Conflict

- Modern Australia: Emerging in the 1960s

- 21st Century: New Challenges and Leadership

- Post-Pandemic: 2022 to Present

- Images for kids

- See also

Indigenous Australia: The First People

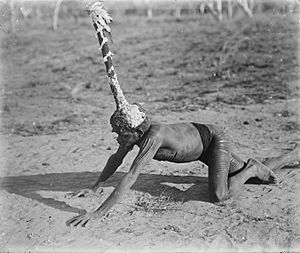

Early History of Indigenous Australians

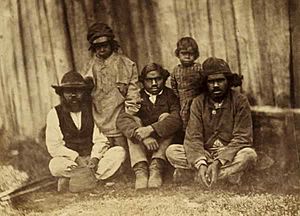

The ancestors of Indigenous Australians are thought to have arrived in Australia between 40,000 and 60,000 years ago. Some even believe it was as early as 70,000 years ago. They lived as hunter-gatherers, meaning they found their food by hunting animals and gathering plants. They also created lasting spiritual and artistic traditions and used stone tools. When Europeans first arrived, it's estimated that at least 350,000 Indigenous people lived in Australia. Some archaeological findings suggest the population might have been as high as 750,000.

Scientists have discussed how the first people arrived. It seems they came by sea during an ice age, when New Guinea and Tasmania were connected to the mainland. Even then, they still needed to travel across water, making them some of the world's earliest sailors. It's hard to know the exact timing because the areas where they likely landed are now under about 50 metres of water.

The oldest known human remains were found at Lake Mungo in New South Wales. These remains suggest one of the world's oldest known cremations, showing early signs of religious practices. In Australian Aboriginal mythology, the Dreaming is a sacred time when ancestral spirit beings created the world. The Dreaming set up the rules for society and the ceremonies performed to keep life and land going. It is still a very important part of Aboriginal art, which is believed to be the oldest continuous art tradition in the world. Aboriginal art can be found all over Australia, like at Uluru and Kakadu National Park.

Historian Manning Clark noted that Aboriginal Australians did not develop farming, likely because there weren't many plants or animals suitable for domestication. This kept the population numbers low. For centuries, Makassan traders from Indonesia visited Australia's north coast to collect trepang (sea cucumbers), trading with the Yolngu people of northeast Arnhem Land.

The largest groups of Aboriginal Australians lived in the southern and eastern parts of the continent, especially near the Murray River. They used resources in a way that allowed them to last, stopping hunting and gathering at certain times to let populations recover. However, the arrival of the first people, along with climate change, might have helped cause the extinction of Australia's megafauna (large animals). The practice of firestick farming in northern Australia, where people used fire to encourage plants that attracted animals, changed dry rainforests into savannas. The introduction of the dingo by Aboriginal people about 3,000–4,000 years ago might have also contributed to the extinction of animals like the thylacine on the mainland.

In 2012, a genetic study suggested that about 4,000 years before the British arrived, some Indian explorers settled in Australia and joined the local population.

Life for Indigenous Australians changed over time. About 10,000–12,000 years ago, Tasmania became separated from the mainland by water. Some stone tool technologies, like attaching stone tools to handles, did not reach the Tasmanian people. In southeastern Australia, near Lake Condah, semi-permanent villages of stone shelters developed near plentiful food sources.

Early European observers had different views of Aboriginal life. Some, like William Dampier, described it as difficult. However, Lieutenant James Cook wondered if the Aboriginal people he met on the east coast were happier than Europeans. Watkin Tench of the First Fleet admired the Aboriginal people of Botany Bay, describing them as good-natured. He also noted conflicts between different Aboriginal groups. Later settlers like Edward Curr observed that Aboriginal Australians "suffered less and enjoyed life more than the majority of civilized men." Historian Geoffrey Blainey wrote that Aboriginal Australians generally had a high standard of living, even higher than many Europeans at the time of Australia's discovery by the Dutch.

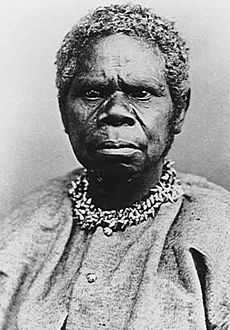

By 1788, the Aboriginal population was made up of 250 different nations. Many of these nations were allied with each other, and each nation had several clans. Each nation had its own language, and some had multiple languages, so over 250 languages existed. About 200 of these languages are now extinct.

Permanent European settlers arrived in Sydney in 1788 and took control of most of the continent by the end of the 1800s. Some Aboriginal societies remained largely unchanged, especially in Northern and Western Australia, until the 1900s. In 1984, a group of Pintupi people from the Gibson Desert were the last to have contact with outsiders. While much knowledge was lost, Aboriginal art, music, and culture survived and are now celebrated by the wider Australian community.

Impact of European Settlement on Indigenous Australians

The first known European landing in Australia was by Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon in 1606. Other Dutch explorers mapped the western and southern coasts, calling the continent New Holland. Macassan traders from Indonesia visited the northern coasts. In 1770, Lieutenant James Cook claimed the east coast for Britain without talking to the people already living there. He suggested Botany Bay (now in Sydney) for a colony.

The first Governor, Arthur Phillip, was told to be friendly with Aboriginal Australians. Interactions between the early settlers and the Indigenous people varied. Some, like Bennelong and Bungaree of Sydney, were curious and cooperative. Bennelong and a friend were the first Australians to sail to Europe and meet King George III. Bungaree travelled with explorer Matthew Flinders on the first trip around Australia. Others, like Pemulwuy and Windradyne from the Sydney area, and Yagan near Perth, resisted the colonists. Pemulwuy was accused of the first killing of a white settler in 1790.

Conflict and Disease

Historian Geoffrey Blainey noted that during the colonial period, there were occasional shootings and spearings in many isolated places. Even worse, diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza spread quickly from one Aboriginal camp to another. Disease and a loss of morale were the main reasons for the decline in Aboriginal populations.

Conflicts in the Hawkesbury Nepean river district near Sydney continued from 1795 to 1816.

Even before European settlers arrived in new areas, Eurasian diseases often reached them first. A smallpox epidemic near Sydney in 1789 wiped out about half the Aboriginal population there. There is debate about where the smallpox came from. Some researchers believe it spread from Indonesian fishermen in the far north. Others argue it was a deliberate act by British marines. Smallpox spread far beyond European settlements, including much of southeastern Australia, and reappeared in 1829–30, killing 40–60% of the Aboriginal population.

The arrival of Europeans greatly disrupted Aboriginal life. While the exact amount of violence is debated, there was significant conflict. Some settlers knew they were taking Aboriginal land. In 1845, Charles Griffiths tried to justify this by asking who had a better right to the land: "the savage, born in a country, which he runs over but can scarcely be said to occupy... or the civilized man, who comes to introduce into this... unproductive country, the industry which supports life."

From the 1960s, Australian writers began to look at European views of Aboriginal Australia differently. Historian Henry Reynolds argued that historians had ignored Aboriginal Australians until the late 1960s. Early writings often suggested Aboriginal Australians were doomed to disappear after Europeans arrived. However, by the early 1970s, historians began to document the conflicts and human cost on the frontier.

Many events show violence and resistance as Aboriginal Australians tried to protect their lands. In May 1804, at Risdon Cove in Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), about 60 Aboriginal Australians were killed. The British set up a new outpost in Tasmania in 1803. Conflicts between colonists and Aboriginal Australians were sometimes called the Black War. The combination of disease, loss of land, intermarriage, and conflict caused the Aboriginal population of Tasmania to drop from a few thousand to a few hundred by the 1830s. Estimates of deaths during this period start around 300, but the true number is impossible to know. In 1830, Governor Sir George Arthur sent an armed group (the Black Line) to push Aboriginal tribes out of British areas. This failed, and George Augustus Robinson tried to make peace with the remaining tribes in 1833. With help from Truganini as a guide, Robinson convinced them to move to an isolated settlement on Flinders Island, where most later died of disease.

In 1838, at least 28 Aboriginal Australians were killed at the Myall Creek massacre in New South Wales. This led to the rare conviction and hanging of six white and one African convict settlers. Aboriginal Australians also attacked white settlers. In 1838, 14 Europeans were killed at Broken River in Port Phillip District by Aboriginal Australians. The most recent massacre of Aboriginal Australians was at Coniston in the Northern Territory in 1928.

From the 1830s, colonial governments created the offices of the Protector of Aborigines to try and prevent mistreatment of Indigenous peoples. Christian churches in Australia tried to convert Aboriginal Australians and often helped carry out welfare and assimilation policies. Early church leaders like Sydney's first Catholic archbishop, John Polding, strongly supported Aboriginal rights. Prominent Aboriginal activist Noel Pearson (born 1965) has written that Christian missions often "provided a haven from the hell of life on the Australian frontier while at the same time facilitating colonisation."

The Caledon Bay crisis of 1932–34 was one of the last violent incidents between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians on the 'frontier'.

Co-operation and Respect

Not all interactions on the frontier were negative. Journals of early European explorers often contain positive accounts of Aboriginal customs and cooperation. Explorers often relied on Aboriginal guides. Charles Sturt used Aboriginal envoys to explore the Murray-Darling region. The only survivor of the Burke and Wills expedition was cared for by local Aboriginal Australians. The famous Aboriginal explorer Jackey Jackey loyally accompanied his friend Edmund Kennedy to Cape York. Respectful studies were done by people like Walter Baldwin Spencer and Frank Gillen in their book The Native Tribes of Central Australia (1899). In inland Australia, the skills of Aboriginal stockmen (people who work with livestock) were highly valued. In the 1900s, Aboriginal stockmen like Vincent Lingiari became national heroes for their fight for better pay and working conditions.

Removal of Children

The removal of Indigenous children was a policy where mixed-race children of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent were taken from their families by government agencies and church missions. This happened between about 1905 and 1969. The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission argued that these removals were an attempt at genocide and had a huge impact on Indigenous people. This part of Aboriginal history is still debated by some historians.

Early European Explorers in Australia

Although some believe the Portuguese discovered Australia in the 1520s, there is no clear proof. The Dutch ship Duyfken, led by Willem Janszoon, made the first recorded European landing in Australia in 1606. That same year, Spanish explorer Luís Vaz de Torres sailed north of Australia through Torres Strait.

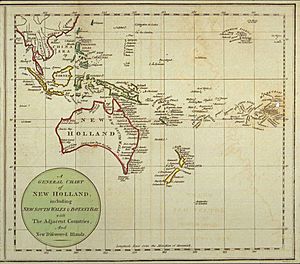

The Dutch, following trade routes to the Dutch East Indies, or searching for gold and spices, greatly increased Europe's knowledge of Australia's coast. In 1616, Dirk Hartog landed on an island off Shark Bay, Western Australia. In 1622–23, the Leeuwin was the first ship to sail around the southwest corner of the continent, giving its name to Cape Leeuwin.

In 1627, the south coast of Australia was accidentally discovered by François Thijssen. In 1628, Dutch ships explored the northern coast, especially the Gulf of Carpentaria, named after Pieter de Carpentier.

Abel Tasman's voyage in 1642 was the first known European trip to reach Van Diemen's Land (later Tasmania) and New Zealand. On his second voyage in 1644, he helped map Australia's north coast.

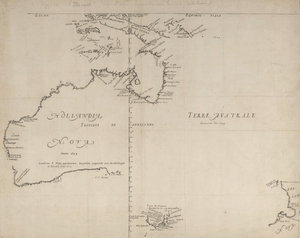

A map in Amsterdam's Town Hall in 1655 showed how much of Australia's coast the Dutch had charted. In 1664, French geographer Melchisédech Thévenot published a map of New Holland. He divided the continent into Nova Hollandia (west) and Terre Australe (east). This map was later copied by Emanuel Bowen in 1747, who added notes encouraging exploration and colonisation.

Despite various ideas for colonisation, none were officially tried. The Dutch East India Company decided there was "no good to be done there" in Australia.

Australia remained largely unvisited by Europeans until the first British explorations. In 1766, John Callander suggested Britain start a colony of banished convicts in the South Sea or Terra Australis to use the riches of those regions.

In 1769, Lieutenant James Cook sailed on the HMS Endeavour to Tahiti. He also had secret orders to find a supposed Southern Continent. He didn't find it, but he decided to map the east coast of New Holland, which the Dutch hadn't charted.

On April 19, 1770, the Endeavour sighted Australia's east coast. Ten days later, they landed at Botany Bay. Cook mapped the coast and, with the ship's naturalist Joseph Banks, reported that Botany Bay was a good place for a colony. Cook officially claimed the east coast of New Holland for Great Britain on August 21/22, 1770.

In 1772, a French expedition led by Louis Aleno de St Aloüarn formally claimed the west coast of Australia, but no colony was started. Sweden's King Gustav III also wanted to start a colony at the Swan River in 1786, but it didn't happen. It wasn't until 1788 that Britain had the right conditions to send the First Fleet to New South Wales.

British Colonisation of Australia

Plans for Colonisation

Seventeen years after Cook landed, the British government decided to establish a colony at Botany Bay. After losing most of its North American colonies in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), Britain looked for new territories. In 1779, Sir Joseph Banks, who had sailed with Cook, suggested Botany Bay as a good place for a settlement. He believed that a land as large as New Holland would offer many benefits. Following Banks' advice, James Matra, who also travelled with Cook, proposed a settlement in New South Wales in 1783. He suggested it could be for American Loyalists, Chinese, and South Sea Islanders, but not convicts.

Matra thought the country was good for growing sugar, cotton, and tobacco. He also believed New Zealand timber and flax could be valuable, and that the colony could be a base for trade in the Pacific. After meeting with Lord Sydney in 1784, Matra changed his plan to include convicts as settlers, thinking it would save money and be more humane.

Matra's plan became the original idea for the settlement. London newspapers announced in November 1784 that a plan for a new colony in New Holland was being considered. The government also decided to include Norfolk Island in their plan, which had valuable timber and flax.

At the same time, people in Britain were campaigning against the terrible conditions in British prisons. Sending criminals to colonies was already common in English law. Before the American Revolution, about a thousand criminals were sent to Maryland and Virginia each year. To convicts in England, being sent to Botany Bay was a terrifying thought, like going to another planet.

Historian Ernest Scott stated the traditional view that the main reason for colonisation was simply to find a place for convicts. However, in the 1960s, historian Geoffrey Blainey suggested other reasons. His book The Tyranny of Distance proposed that securing supplies of flax and timber after losing the American colonies might also have been a reason, with Norfolk Island being key. This led to more research and debate on the reasons for settlement.

The decision to settle was made when it seemed a war in the Netherlands might lead to Britain fighting France, Holland, and Spain again. In this situation, the strategic benefits of a colony in New South Wales, as described in James Matra's plan, were appealing. Matra wrote that such a settlement could help attack Spanish territories in South America and the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies.

Establishing British Colonies

The British claimed all of Australia east of 135° East longitude and Pacific islands between Cape York and Tasmania. This was a huge claim. Spanish and French visitors to Sydney wondered how such a large claim was made without protest.

The colony also included New Zealand. In 1817, the British government removed its claim over the South Pacific islands because the New South Wales government couldn't control the lawlessness there.

1788: New South Wales Colony

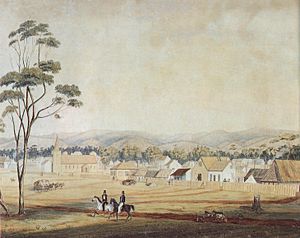

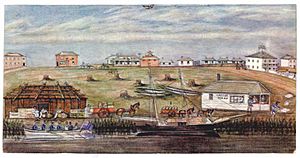

The British colony of New South Wales began when the First Fleet of 11 ships arrived in January 1788. It had over a thousand settlers, including 778 convicts (people sent for crimes). A few days after arriving at Botany Bay, the fleet moved to Port Jackson because it was more suitable. A settlement was started at Sydney Cove on January 26, 1788. This date later became Australia Day, Australia's national holiday. Governor Phillip formally declared the colony on February 7, 1788. Sydney Cove had fresh water and a safe harbour, which Phillip called "the finest Harbour in the World."

Governor Phillip had complete power over the colony's people. He wanted to have good relations with the local Aboriginal people and to reform the convicts. Phillip and his officers wrote journals describing the immense hardships of the first years. Early farming efforts were difficult, and supplies from overseas were scarce. Between 1788 and 1792, about 3,546 male and 766 female convicts arrived. Many were "professional criminals" with few skills needed for a colony. Many new arrivals were also sick. The food situation became critical in 1790. The Second Fleet arrived in June 1790, having lost a quarter of its passengers to sickness. The condition of the convicts on the Third Fleet also shocked Phillip. However, from 1791, ships arrived more regularly, and trade began, improving supplies.

Phillip sent explorers to find better soil. He chose the Parramatta region as a good area for expansion and moved many convicts there from late 1788. Parramatta became the main economic centre of the colony, leaving Sydney Cove as an important port. Poor equipment and unfamiliar soil and climate made farming difficult, but building progressed steadily with convict labour. Between 1788 and 1792, convicts and their guards were most of the population. After this, a population of freed convicts began to grow. They could be given land and started a private economy. Soldiers whose service ended and free settlers from Britain later joined them. Governor Phillip left for England on December 11, 1792, after the new settlement had survived near starvation for four years. On February 16, 1793, the first free settlers arrived.

More Colonies Established

After New South Wales was founded in 1788, Australia was divided into an eastern half (New South Wales) and a western half (New Holland). The western boundary was set at 135° East longitude. This division was meant to prevent future arguments between the Dutch and British.

Romantic descriptions of Norfolk Island led the British government to set up a smaller settlement there in 1788. They hoped the island's giant pine trees and flax plants would create local industries, especially for flax, which was important for British navy ships. However, the island had no safe harbour, so the colony was abandoned in 1807, and settlers moved to Tasmania. The island was later re-settled as a penal colony in 1824.

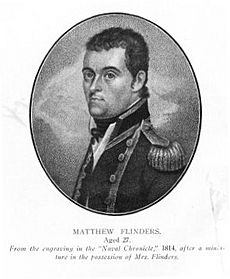

In 1798, George Bass and Matthew Flinders sailed around Tasmania, proving it was an island. In 1802, Flinders successfully sailed around Australia for the first time.

Van Diemen's Land, now Tasmania, was settled in 1803. Other British settlements followed around the continent, many of which failed. In 1823, the East India Trade Committee suggested a settlement on Australia's northern coast to stop the Dutch. Captain J.J.G. Bremer established a settlement at Fort Dundas on Melville Island in 1824. Because this was west of the 1788 boundary, he claimed British rule over all territory as far west as 129° East longitude.

The new boundary included Melville and Bathurst Islands and the nearby mainland. In 1826, the British claim was extended to the whole continent when Major Edmund Lockyer started a settlement at King George Sound (later Albany). In 1824, a penal colony was set up near the Brisbane River (later Queensland). In 1829, the Swan River Colony and its capital Perth were founded on the west coast. Western Australia was initially a free colony but later accepted British convicts due to a shortage of workers.

The colony of South Australia was settled in 1836. Its boundaries were set at 132° and 141° East longitude and 26° South latitude. South Australia was the only colony started by an Act of Parliament and was meant to be developed without cost to the British government. Sending convicts there was forbidden. The law for South Australia included a promise to protect the rights of Aboriginal people to the lands they occupied.

Convicts and Colonial Society

Between 1788 and 1868, about 161,700 convicts (people sent for crimes), including 25,000 women, were sent to New South Wales, Van Diemen's Land, and Western Australia. Most were thieves from working-class towns. Some convicts were able to leave the prison system in Australia. After 1801, they could get "tickets of leave" for good behaviour and work for free men for wages. A few became successful after being pardoned. Female convicts had fewer opportunities.

Some convicts, especially Irish ones, were sent to Australia for political reasons. Because of this, authorities were suspicious of the Irish and limited the practice of Catholicism in Australia. The Irish-led Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804 increased these suspicions. Church of England clergy worked closely with the governors. Richard Johnson, the First Fleet's chaplain, was told to improve "public morality." Reverend Samuel Marsden was also a magistrate and was known as the 'flogging parson' for his harsh punishments.

The New South Wales Corps was formed in 1789 to replace the marines. Officers of the Corps soon became involved in the profitable rum trade. In the Rum Rebellion of 1808, the Corps, working with wool trader John Macarthur, took over the government. They removed Governor William Bligh and ruled for a short time until Governor Lachlan Macquarie arrived in 1810.

Macquarie was the last autocratic Governor of New South Wales, from 1810 to 1821. He played a key role in developing New South Wales from a penal colony to a free society. He started public works, a bank, churches, and charities. He also tried to have good relations with Aboriginal Australians. In 1813, he sent explorers across the Blue Mountains, where they found vast plains. Macquarie believed that freed convicts should be treated as equals to free settlers. He appointed freed convicts to important government jobs. London thought his public works were too expensive, and society was shocked by his treatment of freed convicts. The idea of equality became a central value among Australians.

Early colonial governments wanted to encourage free settlers, but the British government was mostly uninterested. It wasn't until the 1820s that more free settlers arrived. Philanthropists Caroline Chisholm and John Dunmore Lang created their own migration plans. Land was granted by Governors, and schemes like those of Edward Gibbon Wakefield encouraged migrants to travel to Australia instead of the United States or Canada.

Colonial governments wanted to fix the imbalance between men and women in the population. Between 1788 and 1792, about 3,546 male convicts arrived compared to 766 female convicts. Women played an important role in education and welfare. Governor Macquarie's wife, Elizabeth Macquarie, cared about convict women. Elizabeth Macarthur helped start the Australian merino wool industry. The Catholic Sisters of Charity arrived in 1838 and worked in women's prisons, hospitals, and schools. They established hospitals, starting with St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney in 1857, which was free for all, especially the poor. Caroline Chisholm (1808–1877) set up a shelter for migrant women and worked for women's welfare in the 1840s. Her efforts gained her fame in England and support for families in the colony. Sydney's first Catholic Bishop, John Bede Polding, founded an Australian order of nuns, the Sisters of the Good Samaritan, in 1857 to work in education and social work. The Sisters of St Joseph were founded in South Australia by Saint Mary MacKillop and Fr Julian Tenison Woods in 1867. MacKillop travelled throughout Australia and New Zealand, setting up schools and charities. She was canonised (made a saint) by Benedict XVI in 2010, becoming the first Australian to be honoured this way by the Catholic Church.

From the 1820s, more and more squatters (people who occupied land without permission) took over land beyond European settlements. They often raised sheep on large stations and made good profits. By 1834, nearly 2 million kilograms of wool were exported to Britain. By 1850, about 2,000 squatters had gained 30 million hectares of land and became a powerful group.

In 1835, the British Colonial Office issued the Proclamation of Governor Bourke. This law stated that the land belonged to no one before the British Crown took possession of it (the idea of terra nullius). This meant there would be no treaties with Aboriginal peoples. From then on, anyone occupying land without government permission was considered an illegal trespasser.

Separate settlements, and later colonies, were created from parts of New South Wales: South Australia in 1836, New Zealand in 1840, Port Phillip District in 1834 (later Victoria in 1851), and Queensland in 1859. The Northern Territory was founded in 1863 as part of South Australia. The transportation of convicts to Australia gradually stopped between 1840 and 1868.

Vast areas of land were cleared for farming in the first 100 years of European settlement. This, along with the introduction of hard-hoofed animals, greatly affected Indigenous Australians. It reduced their food and shelter resources, forcing them into smaller areas. Many died from new diseases and lack of resources. Indigenous resistance against settlers was widespread. Fighting between 1788 and the 1920s led to the deaths of at least 20,000 Indigenous people and 2,000–2,500 Europeans. In the mid-to-late 1800s, many Indigenous Australians in southeastern Australia were moved, often by force, to reserves and missions. These places often led to quick spread of disease, and many were closed as populations fell.

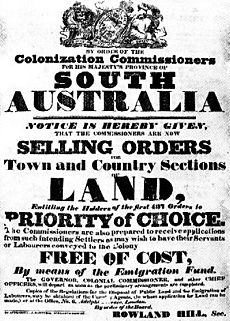

South Australia: A Free Colony

A group in Britain, led by Edward Gibbon Wakefield, wanted to start a colony based on free settlement, not convict labour. In 1831, the South Australian Land Company was formed. They campaigned for a royal charter to establish a privately funded "free" colony in Australia.

While New South Wales, Tasmania, and Western Australia were convict settlements, the founders of South Australia wanted a colony with political and religious freedoms. They also saw opportunities for wealth through business and farming. The South Australia Act 1834, passed by the British Government, reflected these wishes. It promised representative government when the population reached 50,000. South Australia became the only colony authorised by an Act of Parliament and was meant to cost the British government nothing. Sending convicts was forbidden, and poor migrants, helped by an Emigration Fund, had to bring their families. Importantly, the law for South Australia guaranteed the rights of Aboriginal people to the lands they occupied.

In 1836, two ships from the South Australia Land Company left to establish the first settlement on Kangaroo Island. The official founding of South Australia is celebrated on December 28, 1836, when Governor John Hindmarsh proclaimed the new Province at Glenelg. From 1843 to 1851, the Governor ruled with an appointed Executive Council. Land development was central to Wakefield's vision. Land laws allowed land to be bought at a set price, with auctions for popular plots, and leases for unused land. Money from land sales funded the Emigration Fund to help poor settlers come as tradesmen and labourers. People quickly started asking for representative government. In South Australia, power was initially divided between the Governor and the Resident Commissioner, so the government couldn't interfere with business or religious freedom. By 1851, the colony was experimenting with a partially elected council.

Exploring the Continent

In 1798–99, George Bass and Matthew Flinders sailed from Sydney and circumnavigated Tasmania, proving it was an island. In 1801–02, Matthew Flinders led the first circumnavigation of Australia in HMS Investigator. On board was the Aboriginal explorer Bungaree, who became the first person born on the Australian continent to sail around it. Before this, Bennelong and a companion were the first people born in New South Wales to sail to Europe, accompanying Governor Phillip to England in 1792 and meeting King George III.

In 1813, Gregory Blaxland, William Lawson, and William Wentworth successfully crossed the difficult Blue Mountains west of Sydney. At Mount Blaxland, they saw "enough grass to support the stock of the colony for thirty years," allowing British settlement to expand inland.

In 1824, Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane asked Hamilton Hume and Captain William Hovell to find new grazing land in the south and discover where New South Wales' western rivers flowed. Over 16 weeks in 1824–25, Hume and Hovell travelled to Port Phillip and back. They made important discoveries, including the Murray River (which they named the Hume) and good farming lands.

Charles Sturt led an expedition along the Macquarie River in 1828 and discovered the Darling River. People thought inland rivers might drain into an inland sea. In 1829, Sturt followed the Murrumbidgee River into a "broad and noble river," the Murray River, which he named after Sir George Murray. His group followed this river to Lake Alexandrina, where the Murray meets the sea in South Australia. They faced great hardship rowing hundreds of kilometres back upstream.

Surveyor General Sir Thomas Mitchell led expeditions from the 1830s to fill in the map. He carefully recorded original Aboriginal place names, which is why many places still have their Aboriginal names today.

The Polish scientist and explorer Count Paul Edmund Strzelecki surveyed the Australian Alps in 1839. He was the first European to climb Australia's highest peak, which he named Mount Kosciuszko after a Polish patriot.

European explorers made their last great, often difficult and tragic, journeys into Australia's interior in the second half of the 1800s. Some were funded by colonial authorities, others by private investors. By 1850, large inland areas were still unknown to Europeans. Explorers like Edmund Kennedy and Ludwig Leichhardt died trying to map these areas in the 1840s. Expeditions varied in size, from small groups of two or three to large, well-equipped teams with Aboriginal guides, horses, camels, or bullocks.

In 1860, the ill-fated Burke and Wills led the first north-south crossing of the continent from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Burke and Wills died in 1861 after returning to their meeting point at Coopers Creek only to find their party had left hours earlier. The expedition was a navigation success but an organisational disaster.

In 1862, John McDouall Stuart successfully crossed Central Australia from south to north. His expedition mapped the route later used for the Australian Overland Telegraph Line.

Uluru and Kata Tjuta were first mapped by Europeans in 1872. Ernest Giles and William Gosse were the first European explorers to this area. Giles saw Kata Tjuta from near Kings Canyon and called it Mount Olga. The next year, Gosse saw Uluru and named it Ayers Rock. These desert lands were disappointing for farming but later became symbols of Australia.

From Self-Rule to Federation

Colonial Self-Government and Gold Rushes

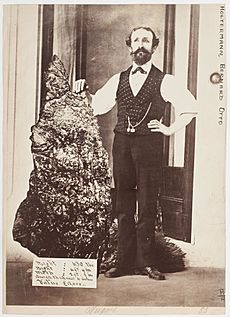

The discovery of gold in Australia is usually credited to Edward Hammond Hargraves near Bathurst, New South Wales, in February 1851. Gold had been found earlier, but because English law said all minerals belonged to the Crown, there wasn't much reason to search for rich goldfields. The California Gold Rush at first overshadowed Australian finds, until news of Mount Alexander reached England in May 1852, followed by ships carrying large amounts of gold.

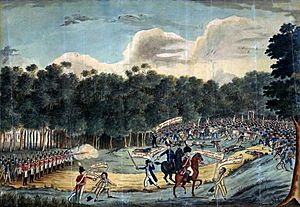

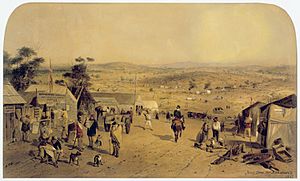

The gold rushes brought many immigrants from Britain, Europe, North America, and China. The population of Victoria grew rapidly, from 76,000 in 1850 to 530,000 by 1859. Miners, called diggers, quickly became unhappy, especially in Victoria, because of how the colonial government managed the goldfields and the gold licence system. After many protests, violence broke out at Ballarat in late 1854.

Early on Sunday, December 3, 1854, British soldiers and police attacked a fort (stockade) built by some unhappy diggers. In a short fight, at least 30 miners were killed. The local Commissioner, Robert Rede, felt it was necessary to strike a blow against the miners.

However, a few months later, a Royal Commission made big changes to how Victoria's goldfields were managed. They recommended getting rid of the licence, reforming the police, and giving voting rights to miners. The Eureka Flag, used by the Ballarat miners, has been considered by some as an alternative to the Australian flag because of its connection to democratic changes.

In the 1890s, author Mark Twain called the battle at Eureka "The finest thing in Australasian history. It was a revolution—small in size, but great politically; it was a strike for liberty, a struggle for principle, a stand against injustice and oppression... it is another instance of a victory won by a lost battle."

Later gold rushes happened at the Palmer River in Queensland in the 1870s, and Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie in Western Australia in the 1890s. Conflicts between Chinese and European miners occurred in Victoria and New South Wales in the late 1850s and early 1860s. These conflicts, driven by European jealousy of Chinese success, helped shape Australian attitudes towards a White Australia policy.

New South Wales was the first colony to gain responsible government in 1855. This meant it managed most of its own affairs while remaining part of the British Empire. Victoria, Tasmania, and South Australia followed in 1856; Queensland in 1859; and Western Australia in 1890. The Colonial Office in London still controlled some matters, like foreign affairs and defence.

The gold era led to a long period of prosperity. This was supported by British investment and the growth of farming and mining, as well as efficient transport by rail, river, and sea. By 1891, Australia had an estimated 100 million sheep. Gold production had decreased since the 1850s but was still worth £5.2 million. Eventually, the economic growth ended, and the 1890s saw an economic depression, especially in Victoria and Melbourne.

However, the late 1800s saw great growth in the cities of southeastern Australia. Australia's population (not including Aboriginal Australians) was 3.7 million in 1900. Almost 1 million of these people lived in Melbourne and Sydney. More than two-thirds of the population lived in cities and towns by the end of the century, making Australia one of the most urbanised societies in the Western world.

Bushrangers: Outlaws of the Bush

Bushrangers were originally runaway convicts in the early days of British settlement. They had the skills to survive in the Australian bush and hide from authorities. The term "bushranger" later referred to those who became outlaws, using the bush as their base. Their crimes often included robbing small-town banks or coach services.

More than 2,000 bushrangers are believed to have roamed the Australian countryside. The first was a convict named Bold Jack Donahue, who was active around 1827. He became a central figure in Australian folklore as the Wild Colonial Boy.

Bushranging was common on the mainland, but Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) had the most violent outbreaks of convict bushrangers. Hundreds of convicts were at large, farms were abandoned, and martial law was declared. Indigenous outlaw Musquito led attacks on settlers.

The peak of bushranging was during the Gold Rush years of the 1850s and 1860s.

There was much bushranging activity in the Lachlan Valley in New South Wales. Frank Gardiner, John Gilbert, and Ben Hall led the most famous gangs of this time. Other active bushrangers included Dan Morgan and Captain Thunderbolt.

As settlement grew, police became more efficient, and transport and communication (like the telegraph) improved, making it harder for bushrangers to escape.

Among the last bushrangers were the Kelly Gang, led by Ned Kelly. They were captured at Glenrowan in 1880. Kelly was born in Victoria to an Irish convict father. As a young man, he had conflicts with the police. After an incident at his home in 1878, police searched for him. After he killed three policemen, Kelly and his gang were declared outlaws.

A final violent fight with police happened at Glenrowan on June 28, 1880. Kelly, wearing homemade metal armour, was captured and jailed. He was hanged for murder in November 1880. His daring and fame made him an iconic figure in Australian history, folklore, literature, art, and film.

Some bushrangers, especially Ned Kelly, presented themselves as political rebels. Australians have mixed feelings about bushrangers, and Kelly is the most well-known example of this.

Development of Australian Democracy

Traditional Aboriginal society was governed by elders and group decision-making. However, the first European-style governments after 1788 were autocratic, run by appointed governors. English law, including ideas from the Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights 1689, was brought to Australia by the colonists. People began asking for representative government soon after the colonies were settled.

The oldest law-making body in Australia, the New South Wales Legislative Council, was created in 1825 to advise the Governor of New South Wales. William Wentworth started the Australian Patriotic Association in 1835, Australia's first political party, to demand democratic government for New South Wales. The reformist Attorney General, John Plunkett, tried to apply Enlightenment principles to government. He extended jury rights to freed convicts and legal protections to convicts and Aboriginal Australians. Plunkett charged the people responsible for the Myall Creek massacre of Aboriginal Australians with murder twice, leading to a conviction. His Church Act of 1836 made all major Christian churches legally equal.

In 1840, the Adelaide City Council and the Sydney City Council were established. Men who owned property worth £1,000 could run for election, and wealthy landowners could have up to four votes. Australia's first parliamentary elections were held for the New South Wales Legislative Council in 1843, with voting rights (for males only) tied to property ownership. Voting rights were extended further in New South Wales in 1850, and elections for legislative councils were held in Victoria, South Australia, and Tasmania.

By the mid-1800s, there was a strong desire for representative and responsible government in the Australian colonies. This was fueled by the democratic spirit of the goldfields (seen at the Eureka Stockade) and reform movements in Europe, the United States, and the British Empire. The end of convict transportation sped up reforms in the 1840s and 1850s. The Australian Colonies Government Act [1850] gave representative constitutions to New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, and Tasmania. The colonies eagerly wrote constitutions that created democratic parliaments. However, the upper houses of these parliaments usually represented social and economic "interests," and all established constitutional monarchies with the British monarch as the symbolic head of state.

In 1855, London granted limited self-government to New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, and Tasmania. An innovative secret ballot system was introduced in Victoria, Tasmania, and South Australia in 1856. In this system, the government provided voting papers, and voters could choose in private. This system was adopted worldwide and became known as the "Australian Ballot". Also in 1855, all male British subjects 21 years or older in South Australia gained the right to vote. This right was extended to Victoria in 1857 and New South Wales the next year. The other colonies followed, until Tasmania became the last to grant universal male suffrage in 1896.

Women who owned property in South Australia were allowed to vote in local elections (but not parliamentary elections) in 1861. Henrietta Dugdale formed the first Australian women's suffrage society in Melbourne in 1884. Women became eligible to vote for the Parliament of South Australia in 1895. This was the first law in the world allowing women to also run for political office. In 1897, Catherine Helen Spence became the first female political candidate, running unsuccessfully for delegate to the Federal Convention on Australian Federation. Western Australia granted voting rights to women in 1899.

Legally, Indigenous Australian males generally gained the right to vote during this period when Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania, and South Australia gave voting rights to all male British subjects over 21. Only Queensland and Western Australia prevented Aboriginal people from voting. Thus, Aboriginal men and women voted in some areas for the first Commonwealth Parliament in 1901. However, early federal laws and court decisions tried to limit Aboriginal voting in practice. This continued until rights activists began campaigning in the 1940s.

Although Australia's parliaments have constantly changed, the main foundations for elected parliamentary government have remained continuous from the 1850s into the 21st century.

Growth of Nationalism

By the late 1880s, most people in the Australian colonies were born in Australia, though over 90% were of British and Irish heritage. Historian Don Gibb suggests that bushranger Ned Kelly represented one aspect of the native-born population's emerging attitudes. Kelly strongly identified with family and friends and opposed what he saw as oppression by police and powerful landowners.

The beginnings of a unique Australian painting style are often linked to this period and the Heidelberg School of the 1880s–1890s. Artists like Arthur Streeton, Frederick McCubbin, and Tom Roberts tried to capture the light and colour of the Australian landscape. Like European Impressionists, they painted outdoors. Their most famous works show scenes of rural and wild Australia, with the bright, sometimes harsh colours of Australian summers.

Australian literature was also developing a distinct voice. Classic Australian writers like Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson, Miles Franklin, and Dorothea Mackellar helped shape this period of growing national identity. Views of Australia sometimes differed. Lawson (a republican socialist) criticised Paterson as a romantic, while Paterson (a country-born city lawyer) thought Lawson was too gloomy. Paterson wrote the lyrics of the beloved folksong Waltzing Matilda in 1895. The song has often been suggested as Australia's national anthem. Advance Australia Fair, the current national anthem, was written in 1887. Mackellar's iconic poem My Country (1903) expressed a love for Australia's "Sunburnt Country" over England's pleasant pastures.

A common theme in the nationalist art, music, and writing of the late 1800s was the romantic rural or bush myth. This was ironic, as Australia was one of the most urbanised societies in the world. Paterson's poem Clancy of the Overflow (1889) captures this romantic myth. While bush ballads were a distinctively Australian popular music and literature form, more classical Australian artists like opera singer Dame Nellie Melba and painters John Peter Russell and Rupert Bunny would later influence Western art and culture abroad.

Federation Movement

Despite some suspicion about the value of nationhood, improvements in transport and communication between colonies, like the telegraph linking Perth to the southeastern cities in 1877, helped reduce rivalries.

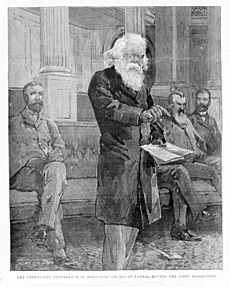

With calls from London for an intercolonial Australian army, and colonies building their own railway lines, New South Wales Premier Henry Parkes spoke in 1889, saying it was time to form a national government. He noted that Australia had a population of three and a half million, similar to the United States when it formed its commonwealth. He believed Australians could achieve in peace what Americans did by war.

Parkes, remembered as the "father of federation," would see his vision achieved within a decade. Growing nationalism, a sense of national identity, better transport and communication, and fears about immigration and defence all encouraged the movement. Despite calls for unification, loyalty to the British Empire remained strong.

In 1890, representatives from the six colonies and New Zealand met in Melbourne and called for a union. The next year, the 1891 National Australasian Convention was held in Sydney. A draft Constitution Bill was created, mainly by Samuel Griffith. Delegates took the Bill back to their parliaments, but progress was slow due to the 1890s economic depression. However, by 1895, five colonies elected representatives for a second Convention held in Adelaide, Sydney, and Melbourne over a year. After much debate, New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania adopted the Bill to be put to their voters. Queensland and Western Australia later did the same.

In July 1898, the Bill was put to referendums (votes by the public) in four colonies, but New South Wales rejected it. In 1899, a second referendum with an amended Bill was put to voters in the four colonies and Queensland, and the Bill was approved.

In March 1900, delegates went to London to get approval for the Bill from the British Parliament. The Bill passed the House of Commons on July 5, 1900, and was signed into law by Queen Victoria on July 9, 1900. Lord Hopetoun was sent from London to appoint an interim government and hold the first elections.

Some colonists, like writer Henry Lawson, had a more radical vision for a separate Australia. But by the end of 1899, after much debate, citizens of five of the six Australian colonies had voted in favour of a constitution to form a Federation. Western Australia voted to join in July 1900. The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act was passed by the British parliament on July 5, 1900, and given Royal Assent by Queen Victoria on July 9, 1900.

Federation: The Birth of a Nation

The Commonwealth of Australia began when the Federal Constitution was announced by the Governor-General, Lord Hopetoun, on January 1, 1901. From then on, a system of federalism in Australia started, creating a new national government (the Commonwealth government) and dividing powers between it and the States. The first Federal elections were held in March 1901. The Protectionist Party won slightly more votes than the Free Trade Party, with the Australian Labor Party (ALP) coming third. Labor said it would support the party that offered concessions, so Edmund Barton's Protectionists formed a government, with Alfred Deakin as Attorney-General.

Barton promised to create a high court, an efficient federal public service, extend conciliation and arbitration (ways to settle disputes), create a uniform railway gauge, introduce voting rights for women, and establish old age pensions. He also promised laws to protect "White Australia" from Asian or Pacific Island workers.

The Labor Party (which dropped the "u" from "Labour" in 1912) was formed in the 1890s after strikes failed. Its strength came from the Australian Trade Union movement, which grew from under 100,000 members in 1901 to over half a million in 1914. The ALP's platform was democratic socialist.

Labor's growing support, and its formation of federal government in 1904 under Chris Watson and again in 1908, helped unite competing conservative, free market, and liberal anti-socialists into the Commonwealth Liberal Party in 1909. The Country Party (today's National Party) was founded in 1913 to represent rural interests.

The Immigration Restriction Act 1901 was one of the first laws passed by the new Australian parliament. This main part of the 'White Australia Policy' aimed to limit immigration from Asia, especially China. It was similar to laws in other settler countries like the United States and Canada. The law allowed a dictation test in any European language to effectively exclude non-"white" immigrants. While the law allowed any European language, the English version became standard. The Labor Party wanted to protect "white" jobs and pushed for stricter limits. A few politicians spoke about avoiding hysterical treatment of the issue. Australia's first Catholic cardinal, Patrick Francis Moran, spoke out against anti-Chinese laws, calling them "unchristian." The popular press mocked his view, and the small European population generally supported the law, fearing being overwhelmed by non-British migrants.

The law passed both houses of Parliament and remained a central part of Australia's immigration laws until the 1950s. In the 1930s, the Lyons government tried to stop Egon Erwin Kisch, a German Czechoslovakian communist writer, from entering Australia using a dictation test in Scottish Gaelic. The High Court of Australia ruled that Scottish Gaelic was not a European language under the Immigration Act. This raised concerns that the law could be used for political reasons.

Before 1901, soldiers from all six Australian colonies fought with British forces in the Second Boer War. When Britain asked for more troops in 1902, Australia sent a national group. About 16,500 men volunteered by the war's end in June 1902. But Australians soon felt vulnerable closer to home. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 meant the Royal Navy withdrew its main ships from the Pacific by 1907. Australians felt like a lonely, sparsely populated outpost in wartime. The visit of the US Navy's Great White Fleet in 1908 showed the government the importance of an Australian navy. The Defence Act of 1909 stressed Australian defence, and in February 1910, Lord Kitchener advised on a defence plan based on conscription. By 1913, the battlecruiser Australia led the new Royal Australian Navy.

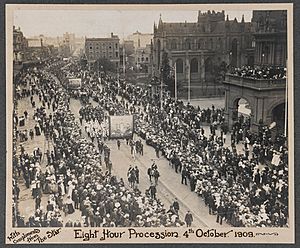

Historian Humphrey McQueen said that working and living conditions for Australia's working classes in the early 1900s were of "frugal comfort." The Court of Conciliation and Arbitration for industrial disputes was set up to create awards, ensuring all workers in an industry had the same conditions and wages. The Harvester Judgment of 1907 recognised the idea of a basic wage. In 1908, the Federal government started an old age pension scheme. These developments, along with the White Australia Policy and pioneering social policies, have been called the Australian settlement. As a result, Australia became known as a place for social experiments and positive liberalism.

Severe droughts in the late 1890s and early 1900s, along with a growing rabbit plague, caused great hardship in rural Australia. Despite this, some writers imagined Australia would become wealthier and more important than Britain, with vast farms and factories.

In 1884, a British protectorate was declared over the southern coast of New Guinea. British New Guinea was fully taken over in 1888. This possession was placed under the authority of the new Commonwealth of Australia in 1902. With the Papua Act of 1905, British New Guinea became the Australian Territory of Papua, with formal Australian administration starting in 1906.

First World War: A Nation Forged in Conflict

When war broke out in Europe in August 1914, all of Britain's colonies and dominions were automatically involved. Prime Minister Andrew Fisher likely spoke for most Australians when he said, "Turn your eyes to the European situation... But should the worst happen... Australians will stand beside our own to help and defend her to the last man and the last shilling."

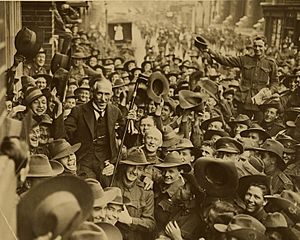

More than 416,000 Australian men volunteered to fight in the First World War between 1914 and 1918, from a total population of 4.9 million. This was between one-third and one-half of all eligible men. The The Sydney Morning Herald called the war Australia's "Baptism of Fire." 8,141 men were killed in 8 months of fighting at Gallipoli, on the Turkish coast. After the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) were withdrawn in late 1915, most were moved to France to serve under British command.

Some forces stayed in the Middle East, including members of the Light Horse Regiment. Light horsemen of the 4th and 12th Regiments captured heavily fortified Beersheba from Turkish forces with a cavalry charge on October 31, 1917. This was one of the last great cavalry charges in history. It opened the way for the allies to outflank the Gaza-Beersheba Line and push the Ottomans back into Palestine.

The AIF's first experience on the Western Front was the most costly single battle in Australian military history. In July 1916, at Fromelles, the AIF suffered 5,533 killed or wounded in 24 hours. Sixteen months later, the five Australian divisions became the Australian Corps, first under General Birdwood and later under Australian General Sir John Monash. Two difficult and divisive conscription referendums were held in Australia in 1916 and 1917. Both failed, and Australia's army remained a volunteer force.

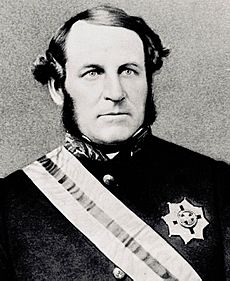

John Monash was appointed commander of the Australian forces in May 1918. He led important attacks in the final stages of the war. British Field Marshal Montgomery later called him "the best general on the western front in Europe." Monash prioritised protecting infantry and used all new war technologies in planning battles. He believed infantry should not be sacrificed needlessly but should "advance under the maximum possible protection of the maximum possible array of mechanical resources." His first operation at the small Battle of Hamel showed his approach worked. Later actions before the Hindenburg Line in 1918 confirmed it. Monash was knighted by King George V after the August 8 advance during the Battle of Amiens. General Erich Ludendorff, the German commander, later called August 8, 1918, "the black day of the German Army." Amiens marked the start of the allied advance that ended the war on November 11.

Over 60,000 Australians died during the conflict, and 160,000 were wounded. This was a high proportion of the 330,000 who fought overseas.

While the Gallipoli campaign was a military failure and 8,100 Australians died, its memory was very important. Gallipoli changed the Australian mindset and became a key part of Australian identity and the founding moment of nationhood. Australia's annual holiday to remember its war dead is ANZAC Day, April 25, the date of the first landings at Gallipoli in 1915.

In 1919, Prime Minister Billy Hughes and former Prime Minister Joseph Cook represented Australia at the Versailles peace conference. Hughes' signing of the Treaty of Versailles was the first time Australia had signed an international treaty. Hughes demanded high payments from Germany and often argued with US President Woodrow Wilson. At one point, Hughes declared, "I speak for 60,000 [Australian] dead."

Hughes demanded that Australia have its own representation within the new League of Nations. He was the strongest opponent of including the Japanese racial equality proposal, which was not included in the final Treaty due to his lobbying. Hughes was worried about Japan's rise. In 1914, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand seized all German possessions in the South West Pacific. Although Japan occupied German possessions with Britain's blessing, Hughes was alarmed. In 1919, at the Peace Conference, the Dominion leaders argued to keep their occupied German possessions. These territories were given as "Class C Mandates" to the Dominions. Japan gained control over the South Pacific Mandate, north of the equator. German New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and Nauru were given to Australia as League of Nations Mandates. Thus, the Territory of New Guinea came under Australian administration.

Between the World Wars

1920s: Men, Money, and Markets

After the war, Prime Minister Billy Hughes led a new conservative party, the Nationalist Party. This party was formed from the old Liberal party and former Labor members, after a deep split over conscription. About 12,000 Australians died from the Spanish flu pandemic of 1919, likely brought home by returning soldiers.

The success of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia seemed like a threat to many Australians, though it inspired a small group of socialists. The Communist Party of Australia was formed in 1920. It had some influence in trade unions but was banned during World War II for supporting the Hitler-Stalin Pact.

The Country Party (today's National Party) formed in 1920 to promote its ideas for rural areas. Its goal was to improve the status of large sheep farmers and small farmers and get subsidies for them. This party has often worked in Coalition with the Liberal Party (since the 1940s) and has been a major government party, especially in Queensland.

Other important effects of the war included ongoing industrial unrest, such as the 1923 Victorian Police strike. Industrial disputes were common in the 1920s. Major strikes also occurred in the waterfront, coal mining, and timber industries in the late 1920s. The union movement established the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) in 1927 to respond to the Nationalist government's efforts to change working conditions and reduce union power.

The consumerism, entertainment culture, and new technologies of the 1920s in the United States were also seen in Australia.

The young film industry declined during the decade. Over 2 million Australians went to cinemas weekly at 1,250 venues. A Royal Commission in 1927 did not help, and the industry, which started brightly with the world's first feature film, The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906), weakened until its revival in the 1970s.

Stanley Bruce became Prime Minister in 1923. In early 1925, Bruce summarised Australia's needs and optimism, saying "men, money and markets accurately defined the essential requirements of Australia." He sought these from Britain. The migration campaign of the 1920s brought almost 300,000 Britons to Australia, though schemes to settle migrants and returned soldiers on the land were generally unsuccessful.

In Australia, state and Federal governments traditionally paid for major investments, borrowing heavily from overseas in the 1920s. A Loan Council was set up in 1928 to coordinate loans, three-quarters of which came from overseas. Despite Imperial Preference (trade benefits for British Empire countries), a good balance of trade with Britain was not achieved. Australia relied dangerously on wheat and wool exports.

Australia adopted new transport and communication technologies. Coastal sailing ships were replaced by steamships, and improvements in rail and motor transport brought big changes to work and leisure. In 1918, there were 50,000 cars and lorries in Australia. By 1929, there were 500,000. The stagecoach company Cobb and Co closed in 1924. In 1920, the Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Service (later Qantas) was established. Reverend John Flynn founded the Royal Flying Doctor Service, the world's first air ambulance, in 1928. Pilot Sir Charles Kingsford Smith pushed flying machines to their limits, completing a round-Australia circuit in 1927 and crossing the Pacific Ocean in 1928 in the aircraft Southern Cross. He became globally famous before disappearing in 1935.

Dominion Status

Australia gained independent status after World War I, under the Statute of Westminster. This law formalised the Balfour Declaration of 1926, which defined Dominions of the British Empire as "autonomous Communities... equal in status, in no way subordinate... though united by a common allegiance to the Crown, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations."

However, Australia did not officially accept the Statute of Westminster until 1942. According to historian Frank Crowley, this was because Australians were not very interested in changing their relationship with Britain until the crisis of World War II.

The Australia Act 1986 removed any remaining legal links between the British Parliament and the Australian states.

From 1927 to 1931, the Northern Territory was divided into North Australia and Central Australia. New South Wales gave up another territory, Jervis Bay Territory, in 1915. External territories were added: Norfolk Island (1914); Ashmore Island, Cartier Islands (1931); the Australian Antarctic Territory from Britain (1933); Heard Island, McDonald Islands, and Macquarie Island from Britain (1947).

The Federal Capital Territory (FCT) was formed from New South Wales in 1911 to provide a location for the new federal capital of Canberra (Melbourne was the seat of government from 1901 to 1927). The FCT was renamed the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) in 1938. The Northern Territory was transferred from South Australian control to the Commonwealth in 1911.

The Great Depression in Australia

Australia was greatly affected by the Great Depression of the 1930s. This was mainly because it relied heavily on exports, especially primary products like wool and wheat. Australia had borrowed a lot of money in the 1920s to fund public works. By 1927, the Australian and state governments were already in a difficult financial situation. Australia's dependence on exports made it very vulnerable to changes in world markets. Debt by New South Wales accounted for almost half of Australia's total debt by December 1927. Some politicians and economists were worried, but most leaders didn't want to admit there were serious problems. As the economy slowed in 1927, manufacturing also slowed, and the country entered a recession as profits dropped and unemployment rose.

In elections held in October 1929, the Labor Party won by a large margin. The new Prime Minister, James Scullin, and his inexperienced government immediately faced many crises. They were limited by not controlling the Senate and by divisions within their party on how to deal with the situation. The government was forced to accept solutions that eventually split the party.

Various "plans" were suggested to solve the crisis. Sir Otto Niemeyer from English banks proposed cutting government spending and wages. Treasurer Ted Theodore suggested a mildly inflationary plan. The Labor Premier of New South Wales, Jack Lang, proposed a radical plan to refuse to pay overseas debt. The "Premier's Plan," finally accepted by federal and state governments in June 1931, followed Niemeyer's deflationary model. It included a 20% cut in government spending, lower bank interest rates, and higher taxes. In March 1931, Lang announced that interest due in London would not be paid, and the Federal government stepped in to pay the debt. In May, the Government Savings Bank of New South Wales had to close. The Melbourne Premiers' Conference agreed to cut wages and pensions, but Lang rejected the plan. The grand opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932 did little to ease the growing crisis. With huge debts, public protests, and conflicts between Lang and the federal governments, the Governor of New South Wales, Philip Game, dismissed Lang on May 13, 1932, because Lang refused to follow legal instructions. In June elections, Lang Labor lost many seats.

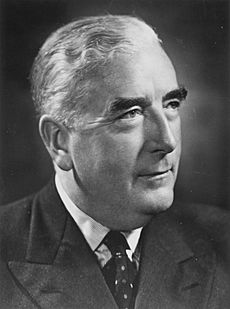

In May 1931, a new conservative political party, the United Australia Party, was formed by former Labor members and the Nationalist Party. In Federal elections in December 1931, the United Australia Party, led by former Labor member Joseph Lyons, easily won. They stayed in power until September 1940. The Lyons government is often credited with leading the recovery from the depression, though how much was due to their policies is debated.

Australia recovered relatively quickly from the financial downturn, with recovery starting around 1932. Prime Minister Joseph Lyons supported the tough economic measures of the Premiers' Plan. He followed a traditional financial policy and refused to accept Jack Lang's proposals to default on overseas debt. According to author Anne Henderson, Lyons believed in "balancing budgets, lowering costs to business and restoring confidence." The Lyons period brought Australia "stability and eventual growth" between the Depression and World War II. Wages were lowered, and industry tariffs were kept, which, along with cheaper raw materials in the 1930s, led to a shift from farming to manufacturing as the main employer. This shift was strengthened by increased government investment in defence. Lyons saw restoring Australia's exports as key to economic recovery.

There is debate about how high unemployment reached in Australia, often cited as peaking at 29% in 1932. However, some historians argue this figure is too low, suggesting a peak national figure of 25%. Unemployment varied greatly. In 1933, in the wealthy Sydney suburb of Woollahra, 17.8% of men and 7.9% of women were unemployed. In the working-class suburb of Paddington, 41.3% of men and 20.7% of women were unemployed. Unemployment was also much higher in some industries, like building, and lower in public administration. In rural areas, small farmers were hit hardest, as more of their income went to interest payments.

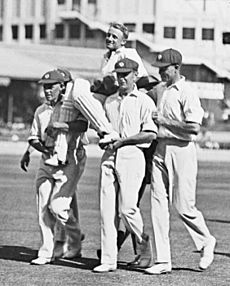

Amazing sporting successes helped lift Australians' spirits during the economic downturn. In a Sheffield Shield cricket match in Sydney in 1930, Don Bradman, a 21-year-old from New South Wales, set a world record by scoring 452 runs not out. His cricketing achievements brought much-needed joy during the Depression. Between 1929 and 1931, the racehorse Phar Lap dominated Australian racing, winning 14 races in a row at one point, including the 1930 Melbourne Cup. Phar Lap went to the United States in 1931 and won North America's richest race in 1932. Soon after, he died with suspicious symptoms. Theories spread that he had been poisoned, and Australians were shocked. The 1938 British Empire Games were held in Sydney, coinciding with Sydney's 150th anniversary of British settlement.

Second World War: A New Alliance

Defence Policy in the 1930s

Until the late 1930s, defence was not a major concern for Australians. At the 1937 elections, both political parties supported increasing defence spending because of Japan's aggression in China and Germany's aggression in Europe. However, they disagreed on how to spend the money. The United Australia Party government focused on working with Britain for "imperial defence." The key to this was the British naval base at Singapore and the Royal Navy fleet that was expected to use it. Defence spending in the years between the wars reflected this priority. Between 1921 and 1936, £40 million was spent on the Royal Australian Navy, £20 million on the Australian Army, and £6 million on the Royal Australian Air Force (established in 1921). In 1939, the Navy was the best-equipped service for war.

Fearing Japan's intentions in the Pacific, Menzies set up independent embassies in Tokyo and Washington to get their own advice. The Labor opposition wanted Australia to be more self-reliant by building up manufacturing and focusing more on the Army and RAAF. In November 1936, Labor leader John Curtin said, "The dependence of Australia upon the competence, let alone the readiness, of British statesmen to send forces to our aid is too dangerous a hazard."

By September 1939, the Australian Army had 3,000 regular soldiers. A recruitment campaign in late 1938, led by Major-General Thomas Blamey, increased the reserve militia to almost 80,000. The first division raised for war was the 6th Division of the 2nd AIF.

Australia at War

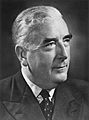

On September 3, 1939, Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced on national radio: "My fellow Australians. It is my melancholy duty to inform you, officially, that, in consequence of the persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her, and that, as a result, Australia is also at war."

This began Australia's involvement in the six-year global conflict. Australians fought in many different places, from stopping Hitler's Panzers in the Siege of Tobruk to pushing back the Imperial Japanese Army in the New Guinea Campaign. They flew bomber missions over Europe, fought naval battles in the Mediterranean, and faced Japanese mini-submarine raids on Sydney Harbour and air raids on Darwin.

A volunteer military force for service at home and abroad, the 2nd Australian Imperial Force, was announced. A citizen militia was organised for local defence. Menzies was careful about sending troops to Europe because Britain had failed to increase defences at Singapore. By the end of June 1940, France, Norway, Denmark, and the Low Countries had fallen to Nazi Germany. Britain stood alone with its dominions. Menzies called for "all-out war," increasing federal powers and introducing conscription.

In January 1941, Menzies flew to Britain to discuss the weakness of Singapore's defences. He was invited to join Winston Churchill's British War Cabinet. When he returned to Australia, with Japan threatening and the Australian army suffering in the Greek and Crete campaigns, Menzies asked the Labor Party to form a War Cabinet. He couldn't get their support and resigned as Prime Minister. The Coalition stayed in office for another month before the independents changed their support, and John Curtin became Prime Minister. Eight weeks later, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

From 1940 to 1941, Australian forces played important roles in the Mediterranean theatre, including the Siege of Tobruk and the Second Battle of El Alamein.

A garrison of about 14,000 Australian soldiers, led by Lieutenant General Leslie Morshead, was surrounded in Tobruk, Libya by the German-Italian army between April and August 1941. The Nazi propagandist Lord Haw Haw called the defenders 'rats,' a name the soldiers adopted with pride: "The Rats of Tobruk". The siege was vital for defending Egypt and the Suez Canal. It stopped the German army's advance for the first time and boosted morale for the British Commonwealth.

The war came closer when HMAS Sydney was lost with all hands in a battle with the German raider Kormoran in November 1941.

With most of Australia's best forces fighting Hitler in the Middle East, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1941 (Australian time). The British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battlecruiser HMS Repulse sent to defend Singapore were sunk soon after. Australia was unprepared for an attack, lacking weapons and modern aircraft. While asking Churchill for reinforcements, Curtin made a historic announcement on December 27, 1941: "The Australian Government... regards the Pacific struggle as primarily one in which the United States and Australia must have the fullest say... Without inhibitions of any kind, I make it clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom."

British Malaya quickly fell, shocking Australia. British, Indian, and Australian troops made a disorganised last stand at Singapore before surrendering on February 15, 1942. About 15,000 Australian soldiers became prisoners of war. Curtin predicted the "battle for Australia" would follow. On February 19, Darwin suffered a devastating air raid, the first time the Australian mainland was attacked by enemy forces. Over the next 19 months, Australia was attacked from the air almost 100 times.

Two experienced Australian divisions were already sailing from the Middle East for Singapore. Churchill wanted them diverted to Burma, but Curtin refused, anxiously awaiting their return to Australia. US President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered his commander in the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur, to create a Pacific defence plan with Australia in March 1942. Curtin agreed to place Australian forces under MacArthur, who became "Supreme Commander of the South West Pacific." Curtin had thus made a major shift in Australia's foreign policy. MacArthur moved his headquarters to Melbourne in March 1942, and American troops began gathering in Australia. In late May 1942, Japanese midget submarines sank a ship in a daring raid on Sydney Harbour. On June 8, 1942, two Japanese submarines briefly shelled Sydney's eastern suburbs and Newcastle.

To isolate Australia, the Japanese planned a sea invasion of Port Moresby, in the Australian Territory of New Guinea. In May 1942, the US Navy fought the Japanese in the Battle of the Coral Sea and stopped the attack. The Battle of Midway in June largely defeated the Japanese navy. The Japanese army then launched a land attack on Moresby from the north. Between July and November 1942, Australian forces pushed back Japanese attempts on the city via the Kokoda Track in New Guinea's highlands. The Battle of Milne Bay in August 1942 was the first Allied defeat of Japanese land forces.

Meanwhile, in North Africa, the Axis Powers had pushed Allies back into Egypt. A turning point came between July and November 1942, when Australia's 9th Division played a crucial role in the heavy fighting of the First and Second Battle of El Alamein. These battles turned the North Africa Campaign in favour of the Allies.

The Battle of Buna–Gona, between November 1942 and January 1943, set the tone for the difficult final stages of the New Guinea campaign, which lasted until 1945. The offensives in Papua and New Guinea in 1943–44 were the largest series of operations ever mounted by the Australian armed forces. On May 14, 1943, the Australian Hospital Ship Centaur, clearly marked as a medical vessel, was sunk by Japanese raiders off the Queensland coast. This killed 268 people, including all but one of the nursing staff, further angering public opinion against Japan.

Australian prisoners of war suffered severe mistreatment in the Pacific. In 1943, 2,815 Australian POWs died building Japan's Burma-Thailand Railway. In 1944, the Japanese forced 2,000 Australian and British prisoners of war on the Sandakan Death March—only 6 survived. This was the single worst war crime against Australians.

MacArthur mostly excluded Australian forces from the main push north into the Philippines and Japan. Australia was left to lead amphibious assaults against Japanese bases in Borneo. Curtin's health suffered from the stress of office, and he died weeks before the war ended. Ben Chifley replaced him.