Australian Aboriginal mythology facts for kids

Australian Aboriginal myths, also known as Dreamtime stories or Songlines, are traditional stories told by the Indigenous people of Australia. Each language group across Australia has its own special stories.

These myths explain important features and meanings in each Aboriginal group's local landscape. They give cultural meaning to Australia's physical land. People who know these stories learn from the wisdom of Aboriginal ancestors from a very long time ago.

David Horton wrote in the Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia that: "A mythic map of Australia would show thousands of characters. They vary in importance, but all are connected to the land. Some appeared at their specific sites and stayed there. Others came from somewhere else and went somewhere else."

"Many could change their shape. They transformed from or into humans, animals, plants, or natural features like rocks. But all left some of their spiritual energy at the places mentioned in their stories."

Australian Aboriginal myths have been described as parts of a catechism (a set of beliefs), a liturgical manual (for religious ceremonies), a history of civilization, a geography textbook, and a guide to the world and the universe.

Contents

Ancient Stories of the Land

An Australian linguist, R. M. W. Dixon, collected many Aboriginal myths in their original languages. He found that some details in these myths matched scientific discoveries about the same landscapes.

For example, on the Atherton Tableland, myths tell how Lake Eacham, Lake Barrine, and Lake Euramo were formed. Geologists have found that the volcanic explosions that created these lakes happened more than 10,000 years ago. Pollen fossil samples from the bottom of the craters agree with the Aboriginal stories. When the craters formed, the area was eucalyptus forest, not the wet tropical rainforest it is today.

Dixon said that Aboriginal myths about the Crater Lakes might be accurate for events from 10,000 years ago. The Australian Heritage Commission listed the Crater Lakes myth on the Register of the National Estate. It was also included in Australia's World Heritage nomination for the wet tropical forests. It is seen as an "unparalleled human record of events dating back to the Pleistocene era."

Since then, Dixon has found many other examples of Aboriginal myths that correctly describe ancient landscapes. He noted many myths about past sea levels, including:

- The Port Phillip myth, collected in 1850, said that Port Phillip Bay was once dry land. The Yarra River used to flow differently, through the Carrum Carrum swamp. This oral history accurately described a landscape from 10,000 years ago.

- The Great Barrier Reef coastline myth, collected near Cairns, described a coastline that was at the edge of the current Great Barrier Reef. It named places now completely under the sea. This oral record was accurate for the landscape 10,000 years ago.

- The Lake Eyre myths, collected in 1906, described Central Australia as fertile, well-watered plains. The deserts around Lake Eyre were once a continuous garden. This oral story matches geologists' understanding that there was a wet period in the early Holocene when the lake would have had permanent water.

Aboriginal Mythology Across Australia

There are at least 400 Aboriginal groups in Australia. Each group has its own name, language, and often its own dialects. Each group also has its own myths, and the words and names in these myths come from these different languages.

With so many different Aboriginal groups, languages, beliefs, and practices, it is hard to describe all myths across the entire continent under one heading.

However, The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia notes that "One interesting feature [of Aboriginal Australian mythology] is the mix of differences and similarities in myths across the entire continent."

Similarities in Aboriginal myths include: "They generally describe the journeys of ancestral beings, often giant animals or people. These beings traveled over what began as a flat land. Mountains, rivers, waterholes, animals, plants, and other natural and cultural things came into being because of events that happened during these Dreamtime journeys. Their existence in today's landscapes is seen by many Indigenous people as proof of their creation beliefs."

"The paths taken by the Creator Beings on their Dreamtime journeys across land and sea link many sacred sites together. They form a network of Dreamtime tracks criss-crossing the country. Dreaming tracks can run for hundreds, even thousands of kilometers, from the desert to the coast. They may be shared by peoples in countries through which the tracks pass."

Australian anthropologists say that Aboriginal myths, still performed today, have an important social function. The myths explain how their daily lives are ordered. They help shape people's ideas and influence how others behave. Also, performances often add and "mythologize" historical events to serve these social purposes in a rapidly changing modern world. As R.M. W. Dixon writes:

"It is always important and common that the Law (Aboriginal law) comes from ancestral peoples or Dreamings. It is passed down through generations in a continuous line. While the rights of particular humans may come and go, the basic connections between foundational Dreamings and certain landscapes are always there. The rights of people to places are usually strongest when those people feel a connection to one or more Dreamings of that place."

This is a very strong part of Aboriginal identity. It is more than just believing. The Dreaming existed, and still exists, while humans are only here for a short time.

Aboriginal myths across Australia are like an unwritten (oral) library. From this library, Aboriginal people learn about the world. They see an Aboriginal 'reality' with ideas and values very different from those of Western societies:

"Aboriginal people learned from their stories that a society must not be human-centered but rather land-centered. Otherwise, they forget their source and purpose. They are connected with the rest of creation. They, as individuals, are only temporary in time, and past and future generations must be included in their view of their purpose in life."

"People come and go, but the Land, and stories about the Land, stay. This wisdom takes lifetimes of listening, watching, and experiencing. There is a deep understanding of human nature and the environment. Sites hold 'feelings' that cannot be described physically. These are subtle feelings that resonate through the bodies of these people. It is only when talking and being with these people that these 'feelings' can truly be understood. This is the intangible reality of these people."

Myths Across Australia

Rainbow Serpent

In 1926, a British anthropologist, Professor Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, noticed that many Aboriginal groups across Australia shared versions of one myth. This myth told of a powerful, creative, and dangerous snake or serpent, usually very large. This serpent was linked with rainbows, rain, rivers, and deep waterholes.

Radcliffe-Brown used the words "Rainbow Serpent" to describe this common myth. He listed different names used across Australia for this "Rainbow Serpent":

- Kanmare (Boulia, Queensland)

- Tulloun: (Mount Isa, Queensland)

- Andrenjinyi (Pennefather River, Queensland)

- Takkan (Maryborough, Queensland)

- Targan (Brisbane, Queensland)

- Kurreah (Broken Hill, New South Wales)

- Wawi (Riverina, New South Wales)

- Neitee & Yeutta (Wilcannia, New South Wales)

- Myndie (Melbourne, Victoria)

- Bunyip (Western Victoria)

- Arkaroo (Flinders Ranges, South Australia)

- Wogal (Perth, Western Australia)

- Wanamangura (Laverton, Western Australia)

- Kajura (Carnarvon, Western Australia)

- Numereji (Kakadu, Northern Territory).

This 'Rainbow Serpent', a huge snake, lives in the deepest waterholes. It came from a larger being that can be seen as a dark streak in the Milky Way. It appears to people as a rainbow as it moves through water and rain. It shapes landscapes, names places, and sometimes drowns people. It can give knowledgeable people rainmaking and healing powers, but it can also cause sores, weakness, illness, and death.

Even Australia's 'Bunyip' was identified as a 'Rainbow Serpent' myth. The words used by Radcliffe-Brown are now commonly used by government groups, museums, art galleries, Aboriginal organizations, and the media to talk about Australian Aboriginal myths.

Captain Cook Myths

Another myth found across Australia is about a person who arrives from the sea. This person, usually from England, either brings gifts or causes great harm. The person is most often called 'Captain Cook' and is often shown as a villain.

The Aboriginal myths about 'Captain Cook' are not historical accounts. They are not about James Cook's actual exploration of Australia's east coast in 1770. Aboriginal people did meet Cook, especially during his seven-week stay on the Endeavour River. The Guugu Yimidhirr people might remember these meetings.

However, the Australia-wide Captain Cook myth tells of a symbolic British character. This character arrives from across the oceans sometime after the Aboriginal world was formed and its original social order was set up. This Captain Cook signals big changes in the social order, into which today's Aboriginal people were born.

In 1988, Australian anthropologist Kenneth Maddock looked at several versions of this 'Captain Cook' myth from different Aboriginal groups:

- Batemans Bay, New South Wales: Percy Mumbulla told how Captain Cook arrived on a large ship at Snapper Island. He gave people clothes and hard biscuits. Then he sailed away. Mumbulla said his ancestors rejected Cook's gifts, throwing them into the sea.

- Cardwell, Queensland: Chloe Grant and Rosie Runaway said Captain Cook and his group seemed to rise from the sea. With white skin, they were thought to be ancestral spirits returning. Captain Cook first offered a pipe and tobacco (which was seen as a 'burning thing'). Then he boiled tea (seen as 'dirty water'). Next, he baked flour on coals (rejected as smelling 'stale'). Finally, he boiled beef (which smelled good and tasted okay once the salty skin was wiped off). Captain Cook and his group then left, sailing north. Chloe Grant and Rosie Runaway's ancestors were sad to see the spirits leave.

- South-eastern side of the Gulf of Carpentaria, Queensland: Rolly Gilbert told how Captain Cook and others sailed the oceans and decided to visit Australia. Cook met some of Rolly's ancestors and was going to shoot them. Instead, he tricked them into showing him the main camping area. After that, he:

"set up the people [cattle industry] to go down the countryside and shoot people down, just like animal, they left them lying there for the hawks and crows...So a lot of old people and young people were struck by the head with the end of a gun and left there. They wanted to get the people wiped out because Europeans in Queensland had to run their stock: horses and cattle."

- Victoria River (Northern Territory): A Captain Cook myth says he sailed from London to Sydney to get land. He brought bullocks and men with firearms. Local Aboriginal people in Sydney were killed. Captain Cook went to Darwin, where he sent armed horsemen to hunt Aborigines in the Victoria River country. He set up Darwin city and gave police and cattle station managers orders on how to treat Aborigines.

- Kimberley (Western Australia): Many Aboriginal storytellers say Captain Cook is a European hero who landed in Australia. Using gunpowder, he set an example for how Aboriginal people were treated across Australia, including the Kimberley. When he returned home, he claimed he had not seen any Aboriginal people. He said the country was empty, and settlers could claim it. In this myth, Captain Cook introduced 'Cook's Law', which settlers use. Aboriginal people say this is a new, unfair, and false law compared to Aboriginal law.

Examples of Myths

Murrinh-Patha People

|

Murrinh-Patha people's country |

The Murrinh-Patha people live in the saltwater country inland from Wadeye. Their myths describe a Dreamtime that anthropologists believe is a religious belief, but different from most other religions.

The Murrinh-Patha have a strong unity in their thoughts, beliefs, and expressions, unlike in Christianity. They see all parts of their lives, thoughts, and culture as being shaped by their Dreaming. They do not see a difference between spiritual or material things. There is no difference between things that are sacred and things that are not. All life is 'sacred', all actions have 'moral' results. All meaning in life comes from this eternal, ever-present Dreaming.

"The sacred is everywhere within the physical landscape. Myths and mythic tracks cross over thousands of miles. Every specific shape and feature of the land has a well-developed 'story' behind it."

This Murrinh-Patha mythology is based on a view of life that believes life is "...a joyous thing with maggots at its center." Life is good and caring, but during life's journey, there are many painful sufferings. Each person must understand and live through these as they grow. This is the message in Murrinh-Patha myths. This philosophy gives Murrinh-Patha people purpose and meaning in life.

For example, the following Murrinh-Patha myth is performed in ceremonies to initiate young men into adulthood: "A woman, Mutjinga (the 'Old Woman'), was in charge of young children. But instead of watching them while their parents were away, she swallowed them. She tried to escape as a giant snake. The people followed her, spearing her and taking the undigested children from her body."

In the myth and its performance, young children must first be swallowed by an ancestral being who turns into a giant snake. The children are then vomited up before being accepted as young adults with all the rights and benefits of young adults.

Pintupi People

|

Pintupi people's country |

The Pintupi people from Australia's Gibson Desert region mostly understand their identity through myths. All events happen and are explained by the social structures and rules told, sung, and performed within their superhuman mythology. This means that the structures of society come from the myths, not from their own political actions, decisions, or the influence of local people.

"The Dreaming provides a moral authority that is outside individual will and human creation. Even though the Dreaming, as an ordering of the cosmos, probably came from historical events, such an origin is denied."

"Current actions are not seen as the result of human alliances, creations, and choices. Instead, they are seen as being set by a larger, cosmic order."

In this Pintupi view of the world, three long geographical tracks of named places control and guide society. These are connected lines of important places named and created by mythical characters as they traveled through the Pintupi desert during the Dreaming. It is a complex mythology of stories, songs, and ceremonies known to the Pintupi as Tingarri. It is most fully told and performed by Pintupi people at larger gatherings in Pintupi country.

See Also

- Beckett, J. (1994) "Aboriginal Histories, Aboriginal Myths: an Introduction", Oceania, Volume 65. pp. 97–115

- Berndt, R. M. & Berndt, C. H. (1989) The Speaking Land. Penguin. Melbourne

- Cowan, James (1994) Myths of the dreaming: interpreting Aboriginal legends. Unity Press. Roseville, N. S. W.

- Dixon, R. M. W. (1996) "Origin legends and linguistic relationships." Oceania, Volume 67. No. 2 pp. 127–140

- Elkin, A. P. (1938) Studies in Australian Totemism. Oceania, Monography No. 2. Sydney

- Haviland, John B., with Hart, Roger. 1998. Old Man Fog and the Last Aborigines of Barrow Point, Crawford House Publishing, Bathurst. ISBN: 1-86333-169-7

- Hiatt, L. (1975) Australian Aboriginal Mythology: Essays in Honour of W. E. H. Stanner, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. Canberra

- Horton, David (1994) The Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander History, Society, and Culture, Aboriginal Studies Press. Canberra. ISBN: 0-85575-234-3

- Isaacs, J. (1980). Australian Dreaming: 40,000 Years of Aboriginal History, Lansdowne Press, Sydney, ISBN: 0-7018-1330-X

- Koepping, Klaus-Peter (1981) "Religion in Aboriginal Australia", Religion, Volume 11. pp. 367–391

- Maddock, K. (1988). "Myth, History and a Sense of Oneself." In Beckett, J. R. (ed) Past and Present: The Construction of Aboriginality. Aboriginal Studies Press. Canberra. pp. 11–30. ISBN: 0-85575-190-8

- Morphy, H. (1992) Ancestral Connections.. University of Chicago Press. Chicago

- Mountford, C. P. (1985) The Dreamtime Book: Australian Aboriginal Myths Louis Braille Productions

- Pohlner, Peter. 1986. gangarru. Hopevale Mission Board, Milton, Queensland. ISBN: 1-86252-311-8

- Radcliffe-Brown, A. R. (1926) "The Rainbow-Serpent Myth of Australia" The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. Volume 56. pp. 19–25

- Roth, W. E. 1897. The Queensland Aborigines. 3 Vols. Reprint: Facsimile Edition, Hesperian Press, Victoria Park, W. A., 1984. ISBN: 0-85905-054-8

- Rumsey, Allen (1994) "The Dreaming, human agency and inscriptive practice". Oceania. Volume 65, Number 2. pp. 116–128

- Smith, W. Ramsay (1932) Myths and Legends of the Australian Aborigines. Farrar & Rinehart, New York, reprinted by Dover, 2003, excerpts available on Google Books. ISBN: 0-486-42709-9

- Sutton, P. (1988) "Myth as History, History as Myth". In Keen, I (ed.) Being Black: Aboriginal Cultures in 'Settled' Australia. Aboriginal Studies Press. Canberra. pp. 251–68

- Stanner, W. E. H. (1966) "On aboriginal religion", Oceania Monograph No. 11. Sydney

- Van Gennep, A (1906) Mythes et Legendes d'Australie. Paris

- Yengoyan, Aram A.(1979) "Economy, Society, and Myth in Aboriginal Australia". Annual Review of Anthropology. Volume 8. pp. 393–415

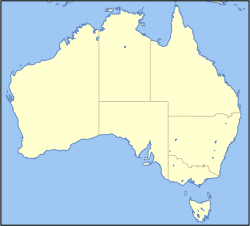

Images for kids

-

Map of the Aboriginal regions in Australia

See also

In Spanish: Mitología aborigen australiana para niños

In Spanish: Mitología aborigen australiana para niños