Eureka Rebellion facts for kids

Eureka Stockade Riot by John Black Henderson (1854).

|

|

| Date | 1851-1854 |

|---|---|

| Location | Colony of Victoria |

| Participants | Gold miners in Victoria and the colonial forces of Australia |

| Outcome |

|

The Eureka Rebellion was a big event in Australia's history. It involved gold miners in the colony of Victoria who stood up against the British government. This happened during the exciting time of the Victorian gold rush. The main clash, known as the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, took place on 3 December 1854 in Ballarat. It was a fight between the miners and the government's soldiers and police. Sadly, 27 people died and many were hurt, mostly miners.

Before the battle, from 1851, miners held many peaceful protests. They also refused to follow some rules. Their main complaints were about the high cost of mining permits. They also disliked how strictly these rules were enforced by officials.

After the battle, 13 captured miners were put on trial for treason. But because so many people supported them, they were all found not guilty. Peter Lalor, a leader of the miners, was later elected to parliament. He even became the Speaker of the Victorian Legislative Assembly. Many changes the miners wanted were put into place. These included giving all adult men the right to vote. They also removed rules about owning property to become a member of parliament. The Eureka Rebellion is often seen as a key moment for democracy in Australia. Many believe it was a fight for political freedom. Today, there's a special place called the Eureka Stockade Memorial Park. It has the Eureka Flag, which the miners promised to protect during the battle.

Contents

- Where the Eureka Rebellion Happened

- The Start of the Conflict

- Early Protests on the Goldfields: 1851–1854

- The Battle of the Eureka Stockade

- After the Battle

- What Eureka Means Today

- Remembering Eureka

- Eureka in Popular Culture

- See also

Where the Eureka Rebellion Happened

The Eureka Rebellion took place in Ballarat, a gold mining town in Victoria. In 1931, someone claimed an old tree stump was where miners gathered. They met there to talk about their problems with the government. This stump was near Victoria Street and Humffray Street. It was also said that Peter Lalor gave a speech there. He led the miners in a promise to fight for their rights.

More recent studies suggest a different spot for this important meeting. In 2015, a report for the City of Ballarat said the most likely place was 29 St. Paul's Way, Bakery Hill. This area was a car park in 2016.

The exact spot of the Eureka Stockade itself is still a mystery. The miners quickly took apart the stockade after the battle. They used the wood for their mines. The whole area was dug up so much that it changed completely. This makes it very hard to find the original location. In 1870, a historian named William Withers described it. He said it was about an acre, fenced with rough wood. It was near Eureka Street, between Stawell and Queen streets.

The Start of the Conflict

After Victoria became separate from New South Wales in 1851, gold was discovered. People were offered money for finding gold near Melbourne. In August 1851, news spread about more gold finds. This caused a "gold fever." Victoria's population grew from 77,000 in 1851 to almost 200,000 in 1853. About 100,000 people lived on the goldfields. Many different types of people came, including some who caused trouble.

The local government struggled to keep up. They didn't have enough police or services. Many workers left their jobs to search for gold. This led to a shortage of workers in other areas.

Early Protests on the Goldfields: 1851–1854

New Mining Tax and Miner Protests

Just days after gold was found, Lieutenant-Governor Charles La Trobe made new rules. On 16 August 1851, he said all goldfield land belonged to the Crown. He also introduced a mining tax of 30 shillings per month. This tax started on 1 September. The tax was the same for everyone, no matter how much gold they found. Miners thought it was unfair. They believed a tax on gold that was actually found would be better. This tax was designed to make it hard for most miners to make a profit.

Miners held many public meetings and sent groups to talk to officials. The first protest was on 26 August 1851 in Buninyong. About 40-50 miners protested the new rules. From the start, there were two groups. Some wanted peaceful, legal changes. Others wanted to use force and even suggested fighting the governor. Protests quickly spread to other mining areas.

First Gold Commissioner Arrives

In September 1851, the first gold commissioner came to Ballarat. In December, miners were upset when the licence fee was set to rise to 3 pounds a month. Some miners in Ballarat even started collecting weapons. On 8 December, a banner against the mining tax was displayed at Forrest Creek.

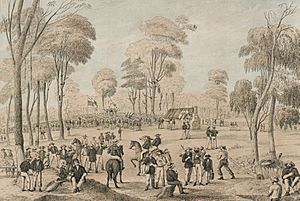

A very large protest, the Forest Creek Monster Meeting, happened on 15 December 1851. Up to 20,000 miners gathered to demand the tax be removed. Two days later, La Trobe cancelled the planned tax increase. However, police continued to hunt for licences often. This made miners very angry. Also, the government strictly banned alcohol sales on the goldfields, which miners disliked.

Even with people moving in and out of the goldfields, anger continued in 1852. Miners complained about bad roads and not enough police. In August 1852, a fight over land rights broke out in Bendigo. An investigation suggested more police were needed. Around this time, the first gold was found at the Eureka lead in Ballarat. In October 1852, miners in Bendigo tried to stop crime themselves. They formed a "Mutual Protection Association." They refused to pay the licence fee and started armed patrols. The government received many complaints about policing. In November 1852, miners attacked a police patrol. They wrongly thought they had to pay a full month's licence for only seven days.

In 1852, the British government decided that Australian colonies could write their own constitutions.

Bendigo Petition and Red Ribbon Movement

In 1853, unrest continued with meetings in Castlemaine, Heathcote, and Bendigo. In February 1853, a policeman accidentally killed William Guest. A thousand angry miners surrounded the government camp. They took police weapons and destroyed some supplies. A meeting called for a full investigation into Guest's death.

The Anti-Gold Licence Association was formed in June in Bendigo. They collected 23,000 signatures for a large petition.

In July 1853, police were attacked with rocks at an anti-licence meeting in Bendigo. On 16 July, 6,000 people protested in Sandhurst. They also raised the issue of not having the right to vote. The goldfields commissioner, William Wright, told La Trobe he supported a tax on gold found, not the unfair monthly tax.

On 3 August, the Bendigo petition was given to La Trobe. He refused to stop the mining tax or give miners the right to vote. The next day, a meeting in Melbourne heard about La Trobe's refusal. The crowd was very unhappy. One leader, George Thompson, joked that if the British flag went, a "diggers' flag" would replace it.

The Bendigo "diggers flag" was shown at a rally on 12 August. Miners marched with flags from many nations, including Irish, Scottish, French, German, and American flags. The Red Ribbon Movement grew in 1853. Supporters wore red ribbons and paid only 10 shillings for the licence fee. They hoped to overwhelm the system with arrests. One report said 10,000 to 12,000 diggers wore red ribbons. Some foreign miners threatened violence if their demands were not met. George Thompson tried to calm them, saying they wanted reform, not revolution. But William Dexter waved the diggers' flag and spoke against "English Tyranny."

On 20 August 1853, authorities released some miners who hadn't paid the tax. This happened just as an angry crowd gathered. A meeting in Beechworth called for a lower licence fee and voting rights. A larger rally of 20,000 people in Bendigo supported a 10-shilling monthly tax. On 28 August, a procession of miners marched past the government camp. They played music, shouted, and fired pistols. On 29 August, an assistant commissioner suggested a peaceful solution could still be found. In Ballarat, miners offered to protect gold reserves from robbers.

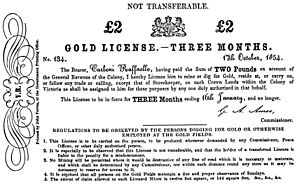

In September 1853, the Legislative Council heard from goldfield activists. A new law, An Act for the Better Management of the Goldfields, was passed. It reduced the licence fee to 40 shillings for three months. But fines for not having a licence increased. Miners also had to carry their permits at all times. This reduction in fees helped calm things for a while. In November, a new plan suggested even lower fees and giving miners voting and land rights. La Trobe changed this plan, making the six-month and 12-month fees higher.

A crowd of 2,000-3,000 attended an anti-licence rally on 3 December 1853. On 31 December 1854, about 500 people gathered to elect a "Diggers Congress."

Inquiry Commission and Licence Hunts

La Trobe cancelled the September 1853 mining tax collections. The Legislative Council supported an inquiry into goldfield complaints. They also thought about removing the licence fee and replacing it with a tax on gold found. In November, the licence fee was brought back. It was on a sliding scale, from 1 pound for one month to 8 pounds for 12 months. Not having a licence meant bigger fines or even jail.

Police, known as "Traps" or "Joes," could check licences at any time. Many police were former convicts and could be brutal. They earned a commission from fines. This led to corruption, with police demanding money from illegal alcohol sellers. Miners were arrested for not carrying their licences. They were sometimes chained to trees overnight. This tax was especially hard on miners who weren't finding much gold.

In March 1854, La Trobe sent a reform plan to the Legislative Council. It was approved and sent to London. It would give all miners the right to vote if they bought a 12-month permit.

Hotham Replaces La Trobe

Sir Charles Hotham became the new lieutenant-governor on 22 June 1854. He ordered strict enforcement of licence rules. He hoped this would make miners leave the goldfields. In August 1854, Hotham visited Ballarat and was well received. But in September, he ordered licence hunts twice a week. More than half the miners still didn't follow the rules.

Raffaello Carboni, a miner, wrote that licence hunts became very frequent. They happened almost every other day in October and November. Miners in Bendigo reacted to these frequent hunts with threats of armed rebellion.

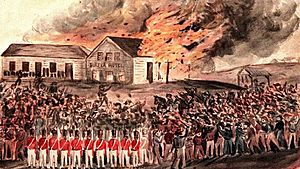

Murder of James Scobie and Bentley's Hotel Fire

In October 1854, a miner named James Scobie was murdered outside the Eureka Hotel. The hotel owners were initially cleared of blame. There were claims that the magistrate in charge was friends with the hotel owner. A disabled servant named Johannes Gregorius was wrongly arrested and treated badly by police. On 15 October, many miners protested Gregorius's treatment. Two days later, after the hotel owners were cleared, about 10,000 men protested near the hotel. The hotel was set on fire, and police couldn't stop the crowd.

On 18 November 1854, Hotham said he sent 450 soldiers and police to Ballarat. They were ordered to keep order and arrest leaders. On 21 October, arrests began for the hotel fire. Andrew McIntyre, Thomas Fletcher, and John Westerby were arrested. Miners gathered and forced their release.

Carboni noted that rewards were offered for information about Scobie's murder and a bank robbery. On 23 October, miners met with Commissioner Rede. They demanded the police involved in Gregorius's arrest be fired. Two days later, a meeting led by Timothy Hayes and John Manning asked Hotham for a new trial for Gregorius. They also wanted a disliked assistant commissioner moved from Ballarat.

On 27 October, Captain Thomas planned the defense of the government outpost. Miners had already been shooting at the barracks at night. On 30 October, Hotham started an inquiry into Scobie's murder. After hearing from the US consul, Hotham released James Tarleton. The inquiry into the Ballarat riots blamed the government camp. It recommended that Magistrate Dewes and Sergeant Major-Milne be dismissed, which happened.

Around 5,000 miners gathered in Bendigo on 1 November. They planned to organize miners at all settlements. Speakers openly called for force.

Ballarat Reform League Meetings

On 11 November 1854, over 10,000 people met at Bakery Hill. The Ballarat Reform League was officially formed. Its chairman was John Basson Humffray, a Chartist. Other leaders were also Chartists. The Ballarat Times reported that the "Union Jack and the American ensign were hoisted." The League adopted principles similar to the British Chartist movement. They declared that "taxation without representation is tyranny." They also said they would leave the United Kingdom if things didn't improve.

For weeks, the League tried to talk with Rede and Hotham. They wanted justice for Bentley and Scobie. They also wanted the men tried for the hotel burning released. They pushed for the abolition of the licence fee, voting rights, and democratic representation for the goldfields. They also wanted the Gold Commission disbanded.

Hotham sent a message to England on 16 November. He said he would start an inquiry into goldfield complaints. He had already noted his opposition to replacing the mining tax with an export duty on gold. The inquiry members were chosen and were expected to be sympathetic to the miners. However, Rede increased the police presence and called for more soldiers from Melbourne. Many historians believe this was because he wanted to show his authority.

The James Scobie murder trial ended on 18 November 1854. James Bentley and two others were found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to hard labor. Catherine Bentley was found not guilty. Two days later, the miners Westerby, Fletcher, and McIntyre were found guilty of burning the Eureka Hotel. They were sentenced to jail. The jury said the local authorities were responsible for the property loss. A week later, a reform league group met with Hotham to ask for the release of the three men. Hotham refused. Father Smyth told Rede that he thought the miners might attack the government outpost.

Miners Prepare for Battle

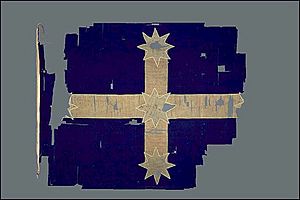

On 29 November, about 10,000 miners met at Bakery Hill again. They heard that their talks with Hotham had failed. The Eureka Flag flew over the platform for the first time. Samuel Douglas Smyth Huyghue, who was there, called it "the symbol of the revolutionary League." Timothy Hayes asked, "Are you ready to die?" Fredrick Vern also spoke. A minister wrote in his diary that miners burned their licences in protest.

Rede ordered a licence search on 30 November. More riots broke out, with miners throwing things at soldiers and police. Eight miners were arrested. Police needed many soldiers to get away from the angry crowd.

Another meeting happened on Bakery Hill. With other leaders absent, Peter Lalor, a more forceful leader, stepped forward. He stood on a tree stump with a rifle and gave a speech. Lalor called for volunteers to join companies and choose captains. He knelt, pointed to the Eureka Flag, and made a famous oath: "We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and fight to defend our rights and liberties." Hotham later reported that the miners had "solemnly consecrated" the Australian flag of independence.

Building the Eureka Stockade

After the oath, about 1,000 miners marched from Bakery Hill to the Eureka lead. They carried the Eureka Flag. They built the stockade between 30 November and 2 December. It was a rough fence made of wood and overturned carts. It covered about an acre.

Lalor said the stockade was just to keep their men together, not for military defense. But others, like Peter FitzSimons, believe Lalor might have downplayed its purpose. The stockade was four to seven feet high in some places. It was hard to cross on horseback. The construction was overseen by Vern, who knew about military methods.

The stockade's location was not good for defense. It was on a gentle slope, leaving its inside exposed to fire. A large group of 800 soldiers with cannons was on its way.

On 1 December, rebels were seen gathering on Bakery Hill. A government group found the area empty. Rede ordered the riot act read again to a crowd near Bath's Hotel. Raffaello Carboni, George Black, and Father Smyth met with Commissioner Rede to offer peace. Rede, suspicious of the miners' political goals, refused.

The rebels sent out scouts to watch Rede's movements. They sent messages to other mining towns asking for help. The "moral force" leaders, like Humffray, left the protest. The rebels continued to build up their position. About 300-400 men arrived from Creswick's Creek. These new arrivals needed food and shelter. By the night before the battle, many rebels had left. Lalor even ordered that anyone leaving should be shot.

The Vinegar Hill Password and Dwindling Numbers

The Argus newspaper reported that a Union Jack flag was flown below the Eureka Flag at the stockade. Some historians wonder if this was true. It might have been a last-minute attempt to keep different groups of miners together. At one point, 1,500 miners were at the stockade. But only about 120 fought in the battle.

Lalor's password for the night of 2 December was "Vinegar Hill." This was the site of a battle during the 1798 Irish rebellion. This password caused many miners to leave. They feared the rebellion was becoming about Irish independence. One survivor said this password was a main reason for the rebellion's collapse. Many Irish miners were at the stockade. The area was mostly Irish. Some believe the white cross on the Eureka Flag is an Irish cross.

Another theory suggests two flags were flown because miners claimed to be defending their British rights. Private Hugh King, a soldier at the battle, said he saw a "white cross of five stars on a blue ground" flag. He also saw a Union Jack flag taken from a prisoner. This suggests the Union Jack might have been taken from the flagpole as miners fled.

Californian Rangers Leave

Many rebels left the stockade on 2 December. A group of 200 Americans, called "The Independent Californian Rangers' Revolver Brigade," arrived. Their leader, James McGill, made a big mistake. He took most of his men away to stop British reinforcements. Many miners also left, thinking the government wouldn't attack on Sunday. Spies told Rede how few miners were left. Estimates say only 120-150 men were at the stockade when the attack happened.

Lalor said there were about 70 men with guns, 30 with pikes, and 30 with pistols. But many had little ammunition. He admired their bravery against the odds. Lalor's plans were known to the government through spies. He had planned to retreat if attacked. But it was too late.

On the night before the battle, Father Smyth asked Catholics to put down their weapons and attend church.

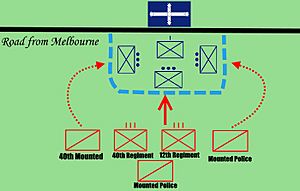

The Battle of the Eureka Stockade

Rede decided to attack the Eureka Stockade when few miners were there. Captain John Thomas led 276 soldiers and police. They planned a surprise attack at dawn on Sunday. The soldiers marched silently at about 3:30 am. The British commander used bugle calls to coordinate his forces. The 40th regiment provided covering fire.

The fighting began when the forces were about 150 yards away. Lalor claimed the government fired first, but other accounts say it was the rebels. The fighting was fierce for at least 10 minutes. The miners put up strong resistance. Thomas's best soldiers even hesitated. This shows how effective the miners' fire was.

Eventually, the rebels ran out of ammunition. The government forces charged forward with bayonets. Lalor was shot in the arm, which later had to be removed. The Eureka flag was captured by Constable John King. The exact number of deaths is unknown. Official records show 27 deaths. Lalor listed 34 rebel casualties, with 22 dead. Captain Thomas reported one soldier killed and two others dying from wounds.

After the Battle

Many historians believe any government would have attacked the stockade. Hotham heard the news of victory the same day. He immediately printed posters asking for public support. A state of martial law was declared, meaning strict military rule. During this time, shots were fired from the government camp, killing several people.

News of the battle quickly reached Melbourne and other goldfields. What the government saw as a victory became a public relations disaster. On 5 December, more soldiers arrived in Ballarat. Reverend Taylor expected more harsh actions. But Major General Nickle, the new commander, was wise and fair. He calmed tensions.

Thousands of people protested in Melbourne. They were angry at the government's actions. Motions supporting the government were met with boos. The mayor quickly ended the meeting. But a new chairman was chosen, and motions condemning the government were passed. Foster, the temporary administrator, resigned. On 6 December 1854, 6,000 people protested outside Saint Paul's Cathedral. Thirteen rebel prisoners were charged with treason. Newspapers also criticized the government's overuse of force.

A Royal Commission was formed on 7 December 1854 to investigate. Hotham still tried to get 1,500 special police from Melbourne and Geelong. He was determined to stop further riots. But in Ballarat, only one man volunteered to join. By early 1855, Ballarat was back to normal.

Hotham became governor in May 1855 but died that New Year's Eve. Foster remained in parliament. Rede was moved from Ballarat but later became sheriff in other towns.

Trials for Treason

The first trial was for Henry Seekamp, editor of the Ballarat Times. He was arrested on 4 December 1854 for articles in his newspaper. He was found guilty of seditious libel in January 1855 and sentenced to six months in prison. He was released early in June 1855. His wife, Clara Seekamp, edited the paper while he was away.

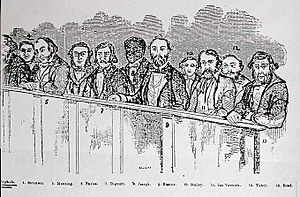

Of the 120 people arrested, 13 were tried for high treason starting on 22 February 1855. A jury of ordinary people, who largely supported the miners, heard the cases. All 13 defendants were found not guilty in seven separate trials. The defendants included:

- Timothy Hayes, chairman of the Ballarat Reform League, from Ireland.

- Raffaello Carboni, an Italian who spoke several languages.

- John Manning, a journalist from Ireland.

- John Joseph, an African American from the United States.

- Jan Vennick, from the Netherlands.

- James Beattie, from Ireland.

- Henry Reid, from Ireland.

- Michael Tuohy, from Ireland.

- James Macfie Campbell, of African ancestry from Jamaica.

- William Molloy, from Ireland.

- Jacob Sorenson, a Jewish man from Scotland.

- Thomas Dignum, born in Sydney.

- John Phelan, a friend of Peter Lalor from Ireland.

John Joseph was the first to be tried. Two soldiers said they saw him fire a shotgun. Butler Cole Aspinall defended Joseph for free. The prosecution was led by William Stawell, the Attorney-General. The Chief Justice was William à Beckett. The jury found Joseph "not guilty" after only half an hour. The Argus reported loud applause in the court. Over 10,000 people came to hear the verdict. Joseph was carried through the streets of Melbourne in triumph.

Manning's case was next. Then, Chief Justice Redmond Barry oversaw the rest of the trials. All the other accused men were found not guilty, except Dignum, whose case was dropped. The trials were seen as a bit of a joke. The British government criticized Hotham for charging the rebels with treason. They said it was hard to prove and juries didn't like it.

Commission of Inquiry Report

The goldfields commission met for the first time on 14 December 1854. In January 1855, they recommended that the mining tax be removed. They also suggested that all those involved in the Eureka Rebellion be pardoned.

The final report of the Royal Commission was given to Hotham on 27 March 1855. It strongly criticized how the goldfields were managed, especially the Eureka Stockade event. Within a year, almost all the Ballarat Reform League's demands were met. Gold licences were abolished and replaced with a tax on exported gold. An annual 1-pound miner's right was introduced. This right gave miners voting rights and a land deed. Mining wardens replaced gold commissioners, and there were fewer police. The Legislative Council was changed to include representatives from the goldfields.

The report also talked about the large number of Chinese immigrants. It called for steps to "check and diminish this influx." This led to a poll tax on Chinese immigrants in June 1855.

Humffray praised the report. He said it was "masterly" and would help the colony if its suggestions were followed.

Peter Lalor Enters Parliament

Lalor wrote that he regretted the miners had to fight. He also regretted they didn't have enough weapons to punish those who caused the outbreak.

In July 1855, Victoria's new constitution was approved. It created a parliament with two houses. All miners who bought a miner's right could vote for the lower house. Lalor and Humffray were appointed to the Legislative Council for Ballarat.

Lalor later upset some of his supporters. He didn't support "one vote, one value." He preferred the old system where owning more property gave you more votes. However, in 1857, all adult men in Victoria got the right to vote. Lalor also opposed paying members of the Legislative Council, which the Ballarat Reform League had wanted. In November 1855, Lalor was elected to the Legislative Assembly.

Some people were surprised that Lalor seemed more interested in gaining status than in the Eureka Rebellion's goals. He lost support from many who had backed him. One person wrote that Lalor changed from a "revolutionary Chief" to a "smug Tory." Lalor defended his views in a letter in 1857. He said he was not a Chartist, Communist, or Republican. But he would always oppose tyrannical governments.

Lalor continued his political career. He served as chairman of committees and later as a minister. He was Speaker of the Legislative Assembly from 1880 to 1887. When he retired due to health, parliament gave him 4,000 pounds. Lalor reportedly refused a British knighthood twice.

What Eureka Means Today

The true political importance of the Eureka Rebellion is still debated. It continues to be a symbol in Australia. Sometimes, people call for the Australian national flag to be replaced by the Eureka Flag. It has been seen in many ways: a fight for freedom against British rule, a protest against unfair taxes, a workers' struggle, or a call for Australia to become a republic.

Some historians think Eureka's importance is exaggerated. They say Australia didn't have a big armed rebellion like the French Revolution or the American Revolutionary War. So, Eureka's story might be made bigger than it was. Others believe Eureka was a very important event that changed Australian history.

Raffaello Carboni, who was there, said that foreign miners didn't care about democracy. They just wanted to resist the licence fee. He also said miners were loyal to the Queen.

American author Mark Twain visited Ballarat. He wrote about Eureka in his book Following the Equator. He called it "the finest thing in Australasian history." He saw it as a small revolution but politically great. He compared it to other important fights for liberty. He said it was a "victory won by a lost battle."

Many Australian leaders have spoken about Eureka. H.V. Evatt, a former Labor leader, said "Australian democracy was born at Eureka." Liberal Prime Minister Robert Menzies called it "an earnest attempt at democratic government." Former Labor Prime Minister Ben Chifley said Eureka was the "first real affirmation of our determination to be masters of our own political destiny."

Historian Geoffrey Blainey said Evatt's view was "slightly inflammatory." He pointed out that the first Australian elections happened in South Australia. Blainey noted that Eureka became a symbol for many groups. He said that while Eureka didn't directly change the constitutions, the new Victorian parliament was influenced by the goldfields' democratic spirit. It passed laws for adult male voting and the secret ballot. Blainey also noted that many miners were temporary migrants. They didn't plan to stay in Australia. So, some saw the rebellion as an uprising by outsiders who didn't want to pay taxes.

In 1999, New South Wales Premier Bob Carr called Eureka a "protest without consequence." Deputy Prime Minister John Anderson said people tried to make too much of it. But in 2004, Victorian Premier Steve Bracks said Eureka was about the struggle for basic democratic rights.

Remembering Eureka

On 22 November 1855, a meeting was held at the stockade site. Carboni returned for the first anniversary of the battle. He sold copies of his book. The next year, veteran John Lynch gave a speech. Hundreds gathered at the Eureka lead and cemetery to remember the battle.

A memorial for the miners was put up in the Ballaarat Old Cemetery on 22 March 1856. It has a pillar with the names of the dead miners. It says they died resisting the government's unfair actions. Soldiers who died were also buried in the same cemetery. A soldiers' memorial was built in 1879.

The Eureka Stockade Memorial in the Eureka Stockade Gardens dates from 1884. It is now on the Australian National Heritage List.

For 30 years, newspapers didn't talk much about Eureka. But people kept its memory alive in Ballarat. Key figures like Lalor and Humffray were still well-known.

The Eureka Flag became a symbol of white nationalism and trade unionism in the late 1800s. It was reportedly displayed at a seamen's union protest in 1878. In 1890, it was shown at a large protest in Melbourne. A similar flag was flown during the 1891 Australian shearers' strike.

In 1889, artists painted a huge canvas of the Eureka Stockade. It was a popular exhibition in Melbourne. People paid to see it and take pictures.

20th Century Commemorations

For the 50th anniversary in 1904, about 60 veterans gathered at the memorial. Large crowds attended. There was a procession and much cheering. Speakers talked about the need for revolt.

In 1954, a committee in Ballarat planned events for the 100th anniversary. There were speeches, a procession, a pageant, and a concert. Soldiers in 1850s uniforms led the procession. The Communist Party of Australia also held events.

Sovereign Hill, a gold rush museum, opened in 1970. Since 1992, it has a night show called "Blood Under the Southern Cross." It tells the story of the Eureka Stockade with sound and light. The Eureka Flag was displayed at Sovereign Hill in 1987 during renovations.

In 1973, Gough Whitlam gave a speech when fragments of the Eureka Flag were put on permanent display. He said Eureka would inspire Australians.

A special interpretation centre was built in Eureka in 1998. It was called the Eureka Stockade Centre, then the Eureka Centre. It had a huge sail with the Eureka Flag. But it didn't attract many tourists. It was redeveloped and reopened in 2013 as the Museum of Australian Democracy at Eureka (MADE). The main exhibit was the Eureka Flag fragments. In 2018, the City of Ballarat took over management, and it's now called the Eureka Centre Ballarat.

21st Century Commemorations

In 2004, the 150th anniversary of the Eureka Stockade was celebrated. The Premier of Victoria, Steve Bracks, announced that the Ballarat train line would be renamed the Eureka Line. Spencer Street railway station was renamed Southern Cross. Bracks said Southern Cross "stands for democracy and freedom because it flew over the Eureka Stockade." A postage stamp and coins were released. A lantern walk was held in Ballarat. However, Prime Minister John Howard did not attend.

The Eureka Tower in Melbourne, finished in 2006, is named after the rebellion. Its design includes blue glass and white stripes, like the Eureka Flag. It also has a gold crown with a red stripe, representing the goldfields and blood spilled.

In 2014, a cartoon called Fall Back with the Eureka Jack was released for the 160th anniversary. On 1 June 2022, a new Pathway of Remembrance was unveiled at the Eureka Stockade Memorial Park. It remembers the "35 men who lost their lives during the Eureka Stockade."

Eureka in Popular Culture

The Eureka Rebellion has inspired many novels, poems, films, songs, and artworks. Much of the Eureka story comes from Raffaello Carboni's 1855 book, The Eureka Stockade. This was the first and only full eyewitness account. Henry Lawson wrote poems about Eureka.

There have been four films based on the uprising. The first was Eureka Stockade in 1907, one of Australia's earliest feature films. There are also plays and songs about the rebellion. The folk song German Teddy is about Edward Thonen, a rebel who died defending the stockade.

See also

In Spanish: Eureka Stockade para niños

In Spanish: Eureka Stockade para niños

- Castle Hill convict rebellion

- Darwin Rebellion

- Eureka Flag

- History of Victoria

- Rum Rebellion

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |